Disorders of Communication

Rhea Paul Ph.D.

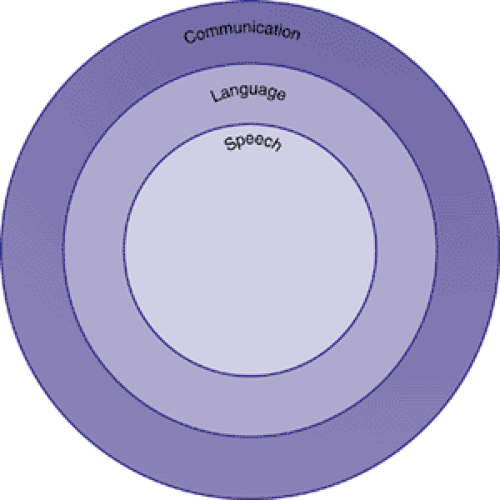

Language, a unique and characteristic capacity of the human mind, is also one of its most vulnerable faculties. Virtually any disruption in cognitive function, particularly during early development, can affect language acquisition. For this reason, disorders of language development typically accompany a variety of conditions, but they can occur in relative isolation as well. It is also true that language is just one form of communication. The term communication refers to all forms of sending and receiving messages, not only with language, but in other ways, such as with gestures, body language, even the way we dress. Animals can also communicate; by means, for example, of their vocalizations to alert others to danger. Figure 5.1.4.1 depicts the relationships among speech, language, and communication. Within the realm of communication, language represents one specific type, which involves generating a potentially infinite set of never-before conveyed messages through the combination of words in rule-governed ways that allow the formation of sentences to express meaning to others. Only humans are truly creative users of language; animals may communicate a limited range of messages, but only humans can express ideas through utterances they create anew without having heard or learned them previously. Speech, on the other hand, is a particular mode of language, its expression through the use of sounds produced by oral movements and gestures. There are other ways to express ideas in language, through writing, for example, that are not speech. It will be helpful to keep these distinctions in mind as we discuss the disorders addressed in this chapter.

Definitions

Communication disorders include any difficulty that affects an individual’s ability to engage in reciprocal social interactions. Thus, communication disorders are defined quite broadly. They can include the problems high-functioning individuals with autism have in engaging in conversation, the deficits in reading and writing seen in children with language-based learning disabilities, or the lack of access to language input seen in people who are deaf. Thus, the term communication disorder subsumes the many kinds of difficulties of speech, language, and social interaction that can affect one’s ability to participate in conversation and social intercourse.

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) has defined language disorder as an impairment in “comprehension and/or use of a spoken, written, and/or other symbol system. The disorder may involve (1) the form of language (phonologic, morphologic, and syntactic systems) (2), the content of language (semantic system), and/or (3) the function of language in communication (pragmatic system), in any combination (1)”. This definition essentially means that a language disorder can be seen as a disruption in any aspect of verbal communication, whether oral or written. It is important to note that this impairment is not necessarily defined only in relation to cognitive level or mental age. Current practice dictates that any child whose language is inadequate for communication can be diagnosed as having a language disorder, even a child who is mentally retarded with a mental age commensurate with his current level of language function. Since

language is a primary and essential form of communication, it is held that all children who have difficulty with understanding or using linguistic communication should have access to services to improve their language function.

language is a primary and essential form of communication, it is held that all children who have difficulty with understanding or using linguistic communication should have access to services to improve their language function.

Speech disorders are more limited difficulties. These refer to problems with the production of oral language, although comprehension may be intact. Speech disorders can affect the fluency of speech (e.g., stuttering), the perceived quality of production (e.g., voice disorders), or the pronunciation of particular sounds (e.g., articulation disorders).

History

Descriptions of the syndrome of disorders of language learning in children date back to at least the early 19th century. Gall (2) was perhaps the first to describe children with poor understanding and use of speech and to differentiate them from the mentally retarded. Subsequently, discoveries about the relations between the brain and language behavior were made by neurologists such as Broca (3) and Wernicke (4). The disorders Gall first identified were thought to be parallel to the aphasias these neurologists were studying in adults. For the first century of the existence of the study of language learning and its disorders, neurologists dominated the field, focusing attention on the physiological substrate of language behavior.

The neurologist Samuel T. Orton (5) can perhaps be thought of as the father of the modern practice of child language disorders. He emphasized the importance not only of neurological but also of behavioral descriptions of the syndrome and pointed out the connections between disorders of language learning and difficulties in the acquisition of reading and writing. In the 1940s and 1950s, other medical professionals, such as psychiatrists and pediatricians, took an interest in children who seemed to be unable to learn language but did not have mental retardation or deafness. Gesell and Amatruda (6) were pioneers in developmental pediatrics and devised innovative techniques for evaluating language development and recognized the condition they called “infantile aphasia.” Benton (7,8) provided us with the fullest descriptions of children with this syndrome and is credited with evolving the concept of a specific disorder of language learning that is structured by excluding other syndromes, rather than by parallels to adult aphasia.

At about the same time as these medical practitioners were refining notions of language disorders, another group of workers was also advancing concepts about children who failed to learn language. Ewing; (9) McGinnis, Kleffner, and Goldstein; (10) and Myklebust (11,12) were all educators of the deaf and, as such, had developed a variety of techniques for teaching language to children who did not talk or hear. They all noticed that some deaf children’s language skills were worse than could be expected on the basis of their hearing impairment alone. This observation led them to focus more interest on the language impairment itself and to attempt to develop more effective methods of remediation for children who did not succeed with the standard approaches that were used to teach language to other children with hearing impairments.

However, until the 1950s, no unified field of endeavor addressing the problems of the language-learning child considered these problems to be disorders of language itself, rather than as a result of some other syndrome (“infantile aphasia” or deafness, for example), or treated language disorders in children regardless of whether the disorder was caused by deafness, mental retardation, or presumed neurological dysfunction. Aram and Nation (13) give credit to three individuals for developing this new field: Mildred A. McGinnis, Helmer R. Myklebust, and Muriel E. Morley. These pioneers integrated the information then available on language disorders in deaf and “aphasic” children and devised educational approaches that could be used to remediate the language dysfunctions demonstrated by these children.