Disorders of Communication

Rhea Paul Ph.D.

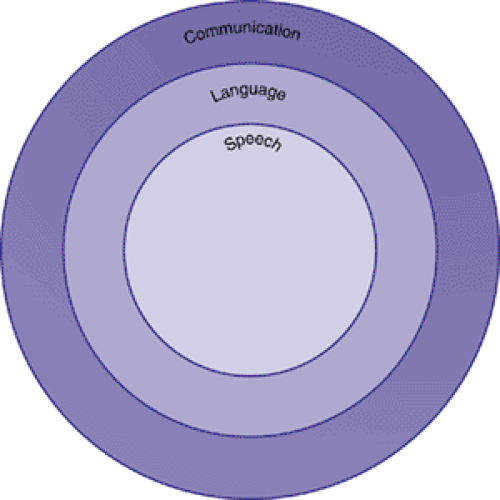

Language, a unique and characteristic capacity of the human mind, is also one of its most vulnerable faculties. Virtually any disruption in cognitive function, particularly during early development, can affect language acquisition. For this reason, disorders of language development typically accompany a variety of conditions, but they can occur in relative isolation as well. It is also true that language is just one form of communication. The term communication refers to all forms of sending and receiving messages, not only with language, but in other ways, such as with gestures, body language, even the way we dress. Animals can also communicate; by means, for example, of their vocalizations to alert others to danger. Figure 5.1.4.1 depicts the relationships among speech, language, and communication. Within the realm of communication, language represents one specific type, which involves generating a potentially infinite set of never-before conveyed messages through the combination of words in rule-governed ways that allow the formation of sentences to express meaning to others. Only humans are truly creative users of language; animals may communicate a limited range of messages, but only humans can express ideas through utterances they create anew without having heard or learned them previously. Speech, on the other hand, is a particular mode of language, its expression through the use of sounds produced by oral movements and gestures. There are other ways to express ideas in language, through writing, for example, that are not speech. It will be helpful to keep these distinctions in mind as we discuss the disorders addressed in this chapter.

Definitions

Communication disorders include any difficulty that affects an individual’s ability to engage in reciprocal social interactions. Thus, communication disorders are defined quite broadly. They can include the problems high-functioning individuals with autism have in engaging in conversation, the deficits in reading and writing seen in children with language-based learning disabilities, or the lack of access to language input seen in people who are deaf. Thus, the term communication disorder subsumes the many kinds of difficulties of speech, language, and social interaction that can affect one’s ability to participate in conversation and social intercourse.

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) has defined language disorder as an impairment in “comprehension and/or use of a spoken, written, and/or other symbol system. The disorder may involve (1) the form of language (phonologic, morphologic, and syntactic systems) (2), the content of language (semantic system), and/or (3) the function of language in communication (pragmatic system), in any combination (1)”. This definition essentially means that a language disorder can be seen as a disruption in any aspect of verbal communication, whether oral or written. It is important to note that this impairment is not necessarily defined only in relation to cognitive level or mental age. Current practice dictates that any child whose language is inadequate for communication can be diagnosed as having a language disorder, even a child who is mentally retarded with a mental age commensurate with his current level of language function. Since

language is a primary and essential form of communication, it is held that all children who have difficulty with understanding or using linguistic communication should have access to services to improve their language function.

language is a primary and essential form of communication, it is held that all children who have difficulty with understanding or using linguistic communication should have access to services to improve their language function.

Speech disorders are more limited difficulties. These refer to problems with the production of oral language, although comprehension may be intact. Speech disorders can affect the fluency of speech (e.g., stuttering), the perceived quality of production (e.g., voice disorders), or the pronunciation of particular sounds (e.g., articulation disorders).

History

Descriptions of the syndrome of disorders of language learning in children date back to at least the early 19th century. Gall (2) was perhaps the first to describe children with poor understanding and use of speech and to differentiate them from the mentally retarded. Subsequently, discoveries about the relations between the brain and language behavior were made by neurologists such as Broca (3) and Wernicke (4). The disorders Gall first identified were thought to be parallel to the aphasias these neurologists were studying in adults. For the first century of the existence of the study of language learning and its disorders, neurologists dominated the field, focusing attention on the physiological substrate of language behavior.

The neurologist Samuel T. Orton (5) can perhaps be thought of as the father of the modern practice of child language disorders. He emphasized the importance not only of neurological but also of behavioral descriptions of the syndrome and pointed out the connections between disorders of language learning and difficulties in the acquisition of reading and writing. In the 1940s and 1950s, other medical professionals, such as psychiatrists and pediatricians, took an interest in children who seemed to be unable to learn language but did not have mental retardation or deafness. Gesell and Amatruda (6) were pioneers in developmental pediatrics and devised innovative techniques for evaluating language development and recognized the condition they called “infantile aphasia.” Benton (7,8) provided us with the fullest descriptions of children with this syndrome and is credited with evolving the concept of a specific disorder of language learning that is structured by excluding other syndromes, rather than by parallels to adult aphasia.

At about the same time as these medical practitioners were refining notions of language disorders, another group of workers was also advancing concepts about children who failed to learn language. Ewing; (9) McGinnis, Kleffner, and Goldstein; (10) and Myklebust (11,12) were all educators of the deaf and, as such, had developed a variety of techniques for teaching language to children who did not talk or hear. They all noticed that some deaf children’s language skills were worse than could be expected on the basis of their hearing impairment alone. This observation led them to focus more interest on the language impairment itself and to attempt to develop more effective methods of remediation for children who did not succeed with the standard approaches that were used to teach language to other children with hearing impairments.

However, until the 1950s, no unified field of endeavor addressing the problems of the language-learning child considered these problems to be disorders of language itself, rather than as a result of some other syndrome (“infantile aphasia” or deafness, for example), or treated language disorders in children regardless of whether the disorder was caused by deafness, mental retardation, or presumed neurological dysfunction. Aram and Nation (13) give credit to three individuals for developing this new field: Mildred A. McGinnis, Helmer R. Myklebust, and Muriel E. Morley. These pioneers integrated the information then available on language disorders in deaf and “aphasic” children and devised educational approaches that could be used to remediate the language dysfunctions demonstrated by these children.

Myklebust (11) perhaps went the furthest in establishing a new and distinct field of study and practice, which he dubbed language pathology. He developed schemes for classifying language disorders in children, which he called auditory disorders, and for differentiating them from deafness and mental retardation. But Myklebust, like Orton, also was concerned with the continuities between disorders of oral language acquisition and their consequences for the acquisition of literacy skills. In founding the new discipline of language pathology, Myklebust pointed the way toward considering language disorders in this broad context, including not only difficulties in producing and comprehending oral language but in the use of written forms of language.

At about the same time that the field of language pathology was being established, the study of language itself was being revolutionized by the introduction of Chomsky’s (14) theory of transformational grammar. This innovation led to an explosion in research and interest in child language acquisition, on which the new discipline of language pathology could draw. This evolving database on normal acquisition provided a blueprint of the language development process that could serve as a curriculum guide for planning intervention.

Epidemiology

Accurate estimates of prevalence of specific language disorders are difficult to come by, because of methodological differences across studies (e.g., in the subclassifications and definitions; in the cutoffs and inclusionary criteria; and in the age, sex, and other characteristics of the children sampled). However, delays in language development are the most common presenting symptom in preschool children (15). Estimates of the prevalence of language difficulty in preschool children vary between 7% and 15% (16,17,18), with an overall median prevalence of 5.9% (19). The prevalence estimate is 8% for boys and 6% for girls (20).

At school age, the prevalence of primary language disorders is thought to be about 4–7% (21), although again there is

overlap with related disorders, because some preschoolers with language disorders “grow into” school-age learning disabilities and dyslexia (22). Specific language disorders and learning disabilities combined are some of the most prevalent disorders of school-age children (23). Although disorders of language expression are thought to be more common than those involving comprehension, Bishop (24) has argued that almost all children with language impairments do have receptive difficulties, although they may be subtle in some cases.

overlap with related disorders, because some preschoolers with language disorders “grow into” school-age learning disabilities and dyslexia (22). Specific language disorders and learning disabilities combined are some of the most prevalent disorders of school-age children (23). Although disorders of language expression are thought to be more common than those involving comprehension, Bishop (24) has argued that almost all children with language impairments do have receptive difficulties, although they may be subtle in some cases.

Etiology

Again, etiological discussions are complicated by the fact that language disorders can exist as circumscribed syndromes, but also accompany a range of other developmental disorders. For this reason, we will restrict our discussion of etiology to specific language impairments (SLI). Although biological markers of SLI have not been identified, neurobiological factors are clearly implicated. There is evidence of genetic factors in SLI (25), including higher concordance in monozygotic than dizygotic twins (26) and higher than normal risk in family members for language and learning problems if a child has SLI (27,28,29). The role of environmental factors in these disorders has long been at issue. Although aberrant parental linguistic input has often been suspected as a cause, numerous researchers (30,31,32,33) have concluded that linguistic input to children with language disorders is adequately matched to the children’s language level. Some environmental factors appear to be associated with risk for language delay, however. These include lower socioeconomic status, larger family size, recurrent otitis media, neglectful home environment, and later birth order (34). It appears that the operative mechanism behind these factors is deprivation of enriching linguistic input (35), occurring at a critical stage in language development.

Just how specific are specific language disorders? Children with SLI are at greatly increased risk for attention and activity problems (36). Other “soft” neurologic signs are also frequently present in children with SLI (8,37). The involvement of a variety of nonverbal cognitive skills in SLI also has been indicated (38,39). These findings have led to the hypothesis that children with SLI may have not just a language problem, but also a general representational deficit, affecting a variety of kinds of symbolic functioning. Tallal (40) cautioned, however, that in each of these studies there were children with SLI who could perform the nonverbal cognitive tasks adequately, and that sometimes the differences between groups were not qualitative, but a matter of speed of response. Leonard (41) pointed out that, although some children with SLI fall below age mates on such tasks, they still do better than younger children with comparable language skills.

Leonard (41,42) provided an alternative explanation for SLI. He contended that children who score low on language tests, relative to their scores on other areas of cognition, may no more have a “disorder” than children who cannot learn to play the violin. He argued that some children are just “limited” in their ability to learn language, falling (as some must) at the low end of the normal distribution of language ability. If this were the case, in his view, it would not be surprising that such children would also be limited in other abilities that related to symbolic function. He referred to Gardner’s (43) notion of “multiple intelligences,” which proposes that there is a variety of somewhat independent spheres of intellectual functioning and that some people have greater abilities in some than others. The tendency to call a language limitation a “handicap” stems, in Leonard’s view, from the importance of linguistic skills for academic and vocational success in our society, not from any significant neurological or neuropsychological pathology in people limited in this way. The fact that language problems tend to aggregate in families (see 39, 44 for review) could be taken to support the view that some people just have fewer optimal “language genes,” and therefore less talent in language areas, than others.

Many would contest this view, however. They would hold that the frequent cooccurrence of SLI with attention and activity problems and other “soft” neurologic signs raises questions about its relation to normal development. Aram (45) argued that children with nearly age-appropriate comprehension but expression limited to single words could not be seen as functioning simply at the low end of the normal range, nor could a 3-year-old who can read but can not produce spontaneous speech (46). Clearly, some children with SLI do have pathologic factors involved. The question for researchers and theoreticians is whether these children are the exception or the rule.

An alternative explanation has been offered by Bishop (24) and Tallal and associates (47). These writers discuss the possibility that SLI is related to deficits in the processing of auditory information, particularly the rapid, short-lived information contained in speech. Tallal and associates have developed an intervention program, known as Fast ForWord, based on this theory. The program trains children to discriminate auditory stimuli on the basis of increasingly brief acoustic cues. Although they have claimed dramatic success in their program, controversy still surrounds these claims at the present writing (48,49).

Newly emerging imaging techniques have demonstrated some differences in brain function between children with and without specific language disorders. Typically, individuals have asymmetrical brains; language structures (such as the planum temporale) tend to be bigger in the left hemisphere. However, children with SLI have generally smaller and more symmetrical brain hemispheres (50). Studies of adults with language difficulties have revealed that they were more likely than individuals with no history of language impairment to have an extra sulcus in Broca’s area, in either brain hemisphere (51). But it is important to realize that no one pattern of brain architecture has been consistently shown in all individuals with language impairment. Instead, these structural differences appear to act as risk factors for language difficulty.

In summary, there is evidence for a genetic component in specific speech and language disorder. However, there are few biological markers of specific language impairment. Although several newly emerging methods have demonstrated differences in the neural structure and auditory functioning of children with SLI, reliable clinical markers have not yet emerged.

Syndromes Involving Communication Disorders

Mental Retardation

Limitation in communicative skill is often one of the first signs of mental retardation. Children with retardation are often first recognized because of their failure to begin talking at the normal time. The sequence of language acquisition in children with retardation follows, in general, the sequence of normal acquisition, although some differences can be identified (52). Many children with mental retardation (MR) show communicative skills that are commensurate with their developmental level, but more than half have language skills that are less than what would be expected for mental age (53). Productive deficits are common, with some children with MR showing deficits relative to mental age in this area only. Others have both receptive and expressive limitations relative to mental age. Phonologic errors are prevalent in children with

MR. These children make similar errors to those seen in normal development, but errors are more frequent (54). Pragmatic skills are usually similar to those seen in children at similar developmental levels (55). The two most prevalent syndromes of MR, Down syndrome (DS) and fragile X syndrome, are both very frequently associated with various problems in language development (56,57). About a third of children with fragile X also exhibit symptoms of autism, whereas social communication skills in children with DS tend to be relatively preserved. Other syndromes, such as Prader-Willi, also exhibit language deficits (52). Even in Williams syndrome, in which it was previously thought that language was stronger than nonverbal ability, recent research has shown that language is preserved relative to nonverbal skills, but does not typically exceed developmental level (58).

MR. These children make similar errors to those seen in normal development, but errors are more frequent (54). Pragmatic skills are usually similar to those seen in children at similar developmental levels (55). The two most prevalent syndromes of MR, Down syndrome (DS) and fragile X syndrome, are both very frequently associated with various problems in language development (56,57). About a third of children with fragile X also exhibit symptoms of autism, whereas social communication skills in children with DS tend to be relatively preserved. Other syndromes, such as Prader-Willi, also exhibit language deficits (52). Even in Williams syndrome, in which it was previously thought that language was stronger than nonverbal ability, recent research has shown that language is preserved relative to nonverbal skills, but does not typically exceed developmental level (58).

Hearing Impairment

Children with impaired hearing are vulnerable to language disorders because of their lack of access to the linguistic information in the auditory signal. Still, children with hearing impairments vary greatly in their oral language ability. With amplification via hearing aids, children can be moved from greater to lesser levels of severity of hearing loss. Cochlear implants and tactile aids are also used to provide auditory information to children who would otherwise be considered deaf (59). In recent years, cochlear implants are being used more routinely at earlier ages to facilitate language development in children born with severe hearing loss, and research (60) suggests this results in very good outcomes in terms of speech and understanding language.

Language acquisition in children with hearing impairment (HI) who do not receive cochlear implants follows the same general sequence as it does in children with normal hearing, although it is greatly delayed, and the delays affect all modalities: articulation, receptive and expressive communication, and oral and written language (61). Use of language for communication is not a major problem area for children with HI. Rather, most of their difficulties lie in acquiring the conventional verbal forms of communication. Reading and writing present particular problems, primarily because of the language basis necessary for acquiring these skills. Average reading comprehension level for adolescents with HI without cochlear implants is third to fourth grade (61,62,63). Language and reading outcomes for children who receive cochlear implants are generally higher (60).

Some children with HI, especially those who come from families in which one or more parent is deaf, can be taught to bypass the auditory channel through the use of manual sign language. Using this method, children can develop fluency and eloquence in Sign that would never be available to them through the modality of speech. There is controversy within the community of the hearing impaired as to the role of Sign language versus oral language instruction for children with severe hearing losses. In general, nonimplanted deaf children taught sign develop higher level language skills than those taught speech, although their communication may be limited to those in the deaf community who use sign as their mode of communication. The widespread use of cochlear implantation has had an effect on the prevalence of the use of Sign, since many implanted children can learn adequately through the auditory channel.

Psychiatric Disorders

There is a very high coincidence of sociobehavioral and communicative disorders (64). Benner, Nelson, and Epstein (65) found, in a metaanalysis, that over 70% of children diagnosed with emotional-behavioral disorders (EBD) had clinically significant language deficits. The deficits were broad based and included expressive, receptive, and pragmatic aspects of language. This finding has been confirmed in studies of bilingual children as well (66). In addition, over 50% of children diagnosed with language deficits also had diagnosable EBD. Further, the number of children who have both communicative and behavioral-socioemotional disorders increases as children with language disorders get older (67). It may be impossible to know the source of this connection. Some writers (68) hold that a communication problem leads to frustration, creating behavioral or emotional disorders. It may, alternatively, be the case that a behavioral/socioemotional problem leads to decreased motivation to communicate or an inability to “tune in” to learn the rules of communication or use language for self- and other-regulation; (69) or, perhaps some other underlying factor affects both aspects of development. Whatever the answer to these questions, children with language problems are vulnerable to socioemotional difficulties, and children with psychiatric diagnoses show a higher than normal prevalence of language disorders. The psychiatric problems that most commonly co-occur with language disorders include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct and oppositional, and anxiety disorders. One particular form of anxiety disorder, selective mutism, has the most obvious communicative concomitants. DSM-IV (70) defines selective mutism as a persistent refusal to talk in one or more major social situations, including school, despite the ability to comprehend and use spoken language (71). The problem has been recognized for at least a century (72) and is relatively rare, with prevalence rates of 0.3 to 0.8 per 1,000 (70). Selective mutism is most often seen in school settings, where the child refuses to speak despite being verbal at home. Cultural and linguistic differences (CLDs) can exacerbate the problem, especially when the child has limited English proficiency (LEP) and feels uncomfortable using the language of the classroom (73). Although most children with CLD eventually overcome their reluctance to talk in school, some, as well as up to 50% of monolingual English speakers who experience selective mutism along with other kinds of school-related anxiety, remain selectively mute for extended periods of time (74). The condition shows a 2:1 ratio in favor of girls (74). In spite of the fact that children with this diagnosis must be known to have the ability to use language in some situations, a high incidence of speech and language difficulties has been reported in this population. Seventy-five percent of selectively mute children have been found to have articulation disorders and expressive language problems; 60% show significant deficits in receptive language (75). Speech-language pathologists often work in collaboration with mental health professionals to address the needs of the selectively mute child. Several recent reports have given examples of effective intervention to deal with selective mutism. These include providing inviting, tempting opportunities to interact with familiar peers, first in small, safe environments within the school setting before attempting speech in the classroom or other public environments. McInnes and Manassis (71) argued that intervention should take into account the child’s social anxiety and begin by encouraging children to answer simple, factual questions (What color is this?) and avoiding questions that require any self-disclosure (What is your favorite color?).

Autism Spectrum Disorders

The psychiatric disorder most consistently associated with communication deficits is pervasive developmental disorder (PDD), or autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Communication problems— including severe delays in language, inability to

communicate nonverbally, inability to sustain conversation, stereotyped and repetitive use of idiosyncratic language, and abnormal ability to use language for social communication— are included in the diagnostic criteria for ASD (70). Virtually all children with autism have some form of communication disorder that presents as part of their syndrome. What differentiates autism from a more circumscribed language disorder is the global nature of the child’s communication problem. Not only is language affected, but the ability and motivation to send messages by any means, verbal or nonverbal, is severely impaired. Although Sign and other alternative forms of communication are often tried with autistic patients, it is their underlying deficit in communicative skill and motivation that impedes their use of language; therefore, providing an alternate channel does not usually result in dramatic improvement (76).

communicate nonverbally, inability to sustain conversation, stereotyped and repetitive use of idiosyncratic language, and abnormal ability to use language for social communication— are included in the diagnostic criteria for ASD (70). Virtually all children with autism have some form of communication disorder that presents as part of their syndrome. What differentiates autism from a more circumscribed language disorder is the global nature of the child’s communication problem. Not only is language affected, but the ability and motivation to send messages by any means, verbal or nonverbal, is severely impaired. Although Sign and other alternative forms of communication are often tried with autistic patients, it is their underlying deficit in communicative skill and motivation that impedes their use of language; therefore, providing an alternate channel does not usually result in dramatic improvement (76).

From early in development, children with ASD show differences in intentional communication. Major differences seen in 1-year-olds later diagnosed with ASD include a lack of joint attentional behavior and an abnormal response to human faces and voices. These babies use gestures to show and point less often than language-matched controls, although they do use gestures to request, protest, and regulate others’ behavior (77). In general, they do not communicate in order to share focus as normal infants do, but only to express wants and needs (78). Some children with ASD do not develop speech, although the proportion who do not is declining as earlier identification and intervention is being implemented (79,80). When speech is absent, it is not spontaneously replaced by communicative gestures, as it is in children with HI, for example. Furthermore, children with ASD may develop maladaptive means for expressing requests and protests. They may begin head-banging, for example, to express rejection of an activity. In children with ASD who do develop speech, some expansion of communicative intentions occurs, along with an elaboration of more socially acceptable means of communicating (76).

Children with ASD who do talk begin speaking late and develop speech at a significantly slower rate than other children (76). About 25% of children with ASD appear to acquire a few words by 12 or 18 months, and then lose them or fail to acquire more (81). When children with ASD begin talking, aspects of language form, including phonology, syntax, and morphology, are relatively spared. These children generally show skills in language form that are at or close to those of mental-age mates (76), although a subgroup of children with ASD show deficits in language form that are similar to those of children with specific language impairment (82). Vocabulary skills also are usually on par with developmental level. Meaning and pragmatic aspects are disproportionately impaired, though (77). When they talk, children with ASD show sparse verbal expression and a lack of spontaneity. They have trouble adapting what they say to the needs and status of the listener, distinguishing given from new information, following politeness rules, making relevant comments, maintaining topics outside their own obsessive interests, and giving listeners their fair share of conversational turns (76).

Children with ASD who talk may use nonreciprocal speech— that is, speech not directed or responsive to others (83). The classic example is from Kanner (84). He told the story of his patient with autism who would scream, “Don’t throw the dog off the balcony” at odd times. The remark was incomprehensible until the boy’s parents explained that he had once been told not to throw a toy dog off the balcony of a hotel in which the family was staying. Ever after this event, he used the statement as an admonition to himself when he had an impulse to do something he shouldn’t do. Such use of language that is “stuck” in its original context, and that cannot be interpreted with only the knowledge that is normally shared among conversational partners, is a classic characteristic of autistic communication. Similarly, speaking children with ASD show extreme literalness in their use of language (76). They have trouble accepting that words can have synonyms or multiple meanings or that there can be different interpretations of the same utterance in contexts such as jokes.

Another classic characteristic of autistic language is echolalia, either immediate or delayed (84,77). Although echolalia was long thought to be a dysfunctional language behavior, investigators such as Fay (85) and Prizant and Duchan (86) have shown that children with ASD often use echolalia for communicative purposes. Echolalia in ASD is selective, as it is in normal development (87). Children with ASD who echo tend to do so when they do not understand what has been said to them or when they lack the language skills to generate an original reply (88). Although echolalia is a “classic” symptom of autistic disorders, not all verbal children with ASD use it. Fay (89) estimated that it appears, at least briefly, in about 75% of autistic children who speak. Also, echolalia is used by children with other syndromes, such as blindness and fragile X syndrome. As language skill in children with ASD improves, echolalia decreases, as it does in normal development.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree