Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders

Five conditions comprise the category of disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders. They include two that are associated with childhood: (1) oppositional defiant disorder and (2) conduct disorder, both of which are discussed in the child psychiatry section of this text in Sections 32.12d and 32.12e, respectively. The remaining three disorders are intermittent explosive disorder, kleptomania, and pyromania, which are discussed in subsequent text of this chapter. Each disorder is characterized by the inability to resist an intense impulse, drive, or temptation to perform a particular act that is obviously harmful to self or others, or both. Before the event, the individual usually experiences mounting tension and arousal, sometimes—but not consistently—mingled with conscious anticipatory pleasure. Completing the action brings immediate gratification and relief. Within a variable time afterward, the individual experiences a conflation of remorse, guilt, self-reproach, and dread. These feelings may stem from obscure unconscious conflicts or awareness of the deed’s impact on others (including the possibility of serious legal consequences in syndromes such as kleptomania). Shameful secretiveness about the repeated impulsive activity frequently expands to pervade the individual’s entire life, often significantly delaying treatment.

ETIOLOGY

Psychodynamic, psychosocial, and biological factors all play an important role in impulse-control disorders; however, the primary causal factor remains unknown. Some impulse-control disorders may have common underlying neurobiological mechanisms. Fatigue, incessant stimulation, and psychic trauma can lower a person’s resistance to control impulses.

Psychodynamic Factors

An impulse is a disposition to act to decrease heightened tension caused by the buildup of instinctual drives or by diminished ego defenses against the drives. The impulse disorders have in common an attempt to bypass the experience of disabling symptoms or painful affects by acting on the environment. In his work with adolescents who were delinquent, August Aichhorn described impulsive behavior as related to a weak superego and weak ego structures associated with psychic trauma produced by childhood deprivation.

Otto Fenichel linked impulsive behavior to attempts to master anxiety, guilt, depression, and other painful affects by means of action. He thought that such actions defend against internal danger and that they produce a distorted aggressive or sexual gratification. To observers, impulsive behaviors may appear irrational and motivated by greed, but they may actually be endeavors to find relief from pain.

Heinz Kohut considered many forms of impulse-control problems, including gambling, kleptomania, and some paraphilic behaviors, to be related to an incomplete sense of self. He observed that when patients do not receive the validating and affirming responses that they seek from persons in significant relationships with them, the self might fragment. As a way of dealing with this fragmentation and regaining a sense of wholeness or cohesion in the self, persons may engage in impulsive behaviors that to others appear self-destructive. Kohut’s formulation has some similarities to Donald Winnicott’s view that impulsive or deviant behavior in children is a way for them to try to recapture a primitive maternal relationship. Winnicott saw such behavior as hopeful in that the child searches for affirmation and love from the mother rather than abandoning any attempt to win her affection.

Patients attempt to master anxiety, guilt, depression, and other painful affects by means of actions, but such actions aimed at obtaining relief seldom succeed even temporarily.

Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial factors implicated causally in impulse-control disorders are related to early life events. The growing child may have had improper models for identification, such as parents who had difficulty controlling impulses. Other psychosocial factors associated with the disorders include exposure to violence in the home, alcohol abuse, promiscuity, and antisocial behavior.

Biological Factors

Many investigators have focused on possible organic factors in the impulse-control disorders, especially for patients with overtly violent behavior. Experiments have shown that impulsive and violent activity is associated with specific brain regions, such as the limbic system, and that the inhibition of such behaviors is associated with other brain regions. A relation has been found between low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) and impulsive aggression. Certain hormones, especially testosterone, have also been associated with violent and aggressive behavior. Some reports have described a relation between temporal lobe epilepsy and certain impulsive violent behaviors, as well as an association of aggressive behavior in patients who have histories of head trauma with increased numbers of emergency room visits and other potential organic antecedents. A high incidence of mixed cerebral dominance may be found in some violent populations.

Considerable evidence indicates that the serotonin neurotransmitter system mediates symptoms evident in impulse-control disorders. Brainstem and CSF levels of 5-HIAA are decreased, and serotonin-binding sites are increased in persons who have committed suicide. The dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems have also been implicated in impulsivity.

Impulse-control disorder symptoms can continue into adulthood in persons whose disorder has been diagnosed as childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Lifelong or acquired mental deficiency, epilepsy, and even reversible brain syndromes have long been implicated in lapses in impulse control.

INTERMITTENT EXPLOSIVE DISORDER

Intermittent explosive disorder manifests as discrete episodes of losing control of aggressive impulses; these episodes can result in serious assault or the destruction of property. The aggressiveness expressed is grossly out of proportion to any stressors that may have helped elicit the episodes. The symptoms, which patients may describe as spells or attacks, appear within minutes or hours and, regardless of duration, remit spontaneously and quickly. After each episode, patients usually show genuine regret or self-reproach, and signs of generalized impulsivity or aggressiveness are absent between episodes. The diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder should not be made if the loss of control can be accounted for by schizophrenia, antisocial or borderline personality disorder, ADHD, conduct disorder, or substance intoxication.

The term epileptoid personality has been used to convey the seizure-like quality of the characteristic outbursts, which are not typical of the patient’s usual behavior, and to convey the suspicion of an organic disease process, for example, damage to the central nervous system. Several associated features suggest the possibility of an epileptoid state: the presence of auras; postictal-like changes in the sensorium, including partial or spotty amnesia; and hypersensitivity to photic, aural, or auditory stimuli.

Epidemiology

Intermittent explosive disorder is underreported. The disorder appears to be more common in men than in women. The men are likely to be found in correctional institutions and the women in psychiatric facilities. In one study, about 2 percent of all persons admitted to a university hospital psychiatric service had disorders that were diagnosed as intermittent explosive disorder; 80 percent were men.

Evidence indicates that intermittent explosive disorder is more common in first-degree biological relatives of persons with the disorder than in the general population. Many factors other than a simple genetic explanation may be responsible.

Comorbidity

High rates of fire setting in patients with intermittent explosive disorder have been reported. Other disorders of impulse control and substance use and mood, anxiety, and eating disorders have also been associated with intermittent explosive disorder.

Etiology

Psychodynamic Factors. Psychoanalysts have suggested that explosive outbursts occur as a defense against narcissistic injurious events. Rage outbursts serve as interpersonal distance and protect against any further narcissistic injury.

Psychosocial Factors. Typical patients have been described as physically large, but dependent, men whose sense of masculine identity is poor. A sense of being useless and impotent or of being unable to change the environment often precedes an episode of physical violence, and a high level of anxiety, guilt, and depression usually follows an episode.

An unfavorable childhood environment often filled with alcohol dependence, beatings, and threats to life is usual in these patients. Predisposing factors in infancy and childhood include perinatal trauma, infantile seizures, head trauma, encephalitis, minimal brain dysfunction, and hyperactivity. Investigators who have concentrated on psychogenesis as causing episodic explosiveness have stressed identification with assaultive parental figures as symbols of the target for violence. Early frustration, oppression, and hostility have been noted as predisposing factors. Situations that are directly or symbolically reminiscent of early deprivations (e.g., persons who directly or indirectly evoke the image of the frustrating parent) become targets for destructive hostility.

Biological Factors. Some investigators suggest that disordered brain physiology, particularly in the limbic system, is involved in most cases of episodic violence. Compelling evidence indicates that serotonergic neurons mediate behavioral inhibition. Decreased serotonergic transmission, which can be induced by inhibiting serotonin synthesis or by antagonizing its effects, decreases the effect of punishment as a deterrent to behavior. The restoration of serotonin activity, by administering serotonin precursors such as L-tryptophan or drugs that increase synaptic serotonin levels, restores the behavioral effect of punishment. Restoring serotonergic activity by administration of L-tryptophan or drugs that increase synaptic serotonergic levels appears to restore control of episodic violent tendencies. Low levels of CSF 5-HIAA have been correlated with impulsive aggression. High CSF testosterone concentrations are correlated with aggressiveness and interpersonal violence in men. Antiandrogenic agents have been shown to decrease aggression.

Familial and Genetic Factors. First-degree relatives of patients with intermittent explosive disorder have higher rates of impulse-control disorders, depressive disorders, and substance use disorders. Biological relatives of patients with the disorder were more likely to have histories of temper or explosive outbursts than the general population.

Diagnosis and Clinical Features

The diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder should be the result of history-taking that reveals several episodes of loss of control associated with aggressive outbursts (Table 19-1). One discrete episode does not justify the diagnosis. The histories typically describe a childhood in an atmosphere of alcohol dependence, violence, and emotional instability. Patients’ work histories are poor; they report job losses, marital difficulties, and trouble with the law. Most patients have sought psychiatric help in the past but to no avail. Anxiety, guilt, and depression usually follow an outburst, but this is not a constant finding. Neurological examination sometimes reveals soft neurological signs, such as left–right ambivalence and perceptual reversal. Electroencephalography (EEG) findings are frequently normal or show nonspecific changes.

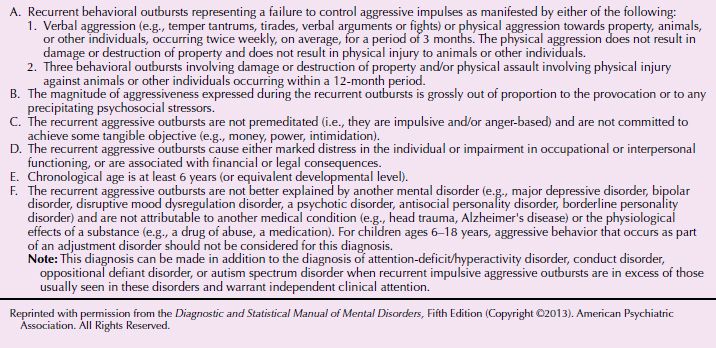

Table 19-1

Table 19-1

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Intermittent Explosive Disorder

A 36-year-old real estate agent sought assistance for difficulty with his anger. He was quite competent at his job, although he frequently lost clients when he became enraged over their indecisiveness. On a number of occasions, he became verbally abusive, leading clients to find ways out of escrow closings. The impulsive aggression also led to termination of multiple relationships because sudden angry outbursts contained demeaning accusations toward his girlfriends. This occurred frequently in the absence of any clear conflict. On multiple occasions, the patient became so uncontrollably enraged that he threw things across the room, including books, his desk, and the contents of the refrigerator. Between episodes, he was a kind and likable individual with many friends. He enjoyed drinking on the weekends and had a history of two arrests for driving while intoxicated. On one of these occasions, he became involved in a verbal altercation with a police officer. He had a history of drug experimentation in college that included cocaine and marijuana.

Mental status examination revealed a generally cooperative patient. However, he became quite defensive when questioned about his anger and easily felt accused and blamed by the interviewer for his past behaviors. He had no significant medical history and no signs of neurological problems. He had never been in psychiatric treatment prior to this evaluation. He was on no medications. He denied any symptoms of a mood disorder or any other antisocial activity.

Treatment included the use of carbamazepine (Tegretol) and a combination of supportive and cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy. The patient’s angry outbursts improved as he became aware of early signs that he was about to lose control. He learned techniques to avoid confrontation when he was faced with these warning signs. (Courtesy of Vivien K. Burt, M.D., Ph.D., and Jeffrey William Katzman, M.D.)

Physical Findings and Laboratory Examination

Persons with the disorder have a high incidence of soft neurological signs (e.g., reflex asymmetries), nonspecific EEG findings, abnormal neuropsychological testing results (e.g., letter reversal difficulties), and accident susceptibility. Blood chemistry (liver and thyroid function tests, fasting blood glucose, electrolytes), urinalysis (including drug toxicology), and syphilis serology may help rule out other causes of aggression. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may reveal changes in the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with loss of impulse control.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder can be made only after disorders associated with the occasional loss of control of aggressive impulses have been ruled out as the primary cause. These other disorders include psychotic disorders, personality change because of a general medical condition, antisocial or borderline personality disorder, and substance intoxication (e.g., alcohol, barbiturates, hallucinogens, and amphetamines), epilepsy, brain tumors, degenerative diseases, and endocrine disorders.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree