Dissociative Disorders

In psychiatry, dissociation is defined as an unconscious defense mechanism involving the segregation of any group of mental or behavioral processes from the rest of the person’s psychic activity. Dissociative disorders involve this mechanism so that there is a disruption in one or more mental functions, such as memory, identity, perception, consciousness, or motor behavior. The disturbance may be sudden or gradual, transient or chronic, and the signs and symptoms of the disorder are often caused by psychological trauma.

Amnesia brought on by intrapsychic conflict is coded differently from amnesia brought on by a medical condition such as encephalitis. In the latter case, according to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a diagnosis of neurocognitive disorder due to a medical condition would be made; whereas in the former condition, a diagnosis of dissociative amnesia would be made. (See Section 21.4 which discusses neurocognitive disorders brought on by another medical condition [amnestic disorder] for a further discussion of this topic.)

DISSOCIATIVE AMNESIA

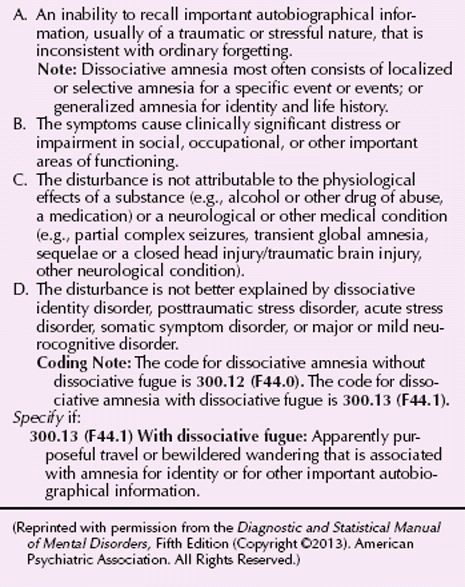

The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for dissociative amnesia are listed in Table 12-1. The main feature of dissociative amnesia is an inability to recall important personal information, usually of a traumatic or stressful nature, that is too extensive to be explained by normal forgetfulness. And, as mentioned above, the disorder does not result from the direct physiological effects of a substance or a neurological or other general medical condition. The different types of dissociative amnesia are listed in Table 12-2.

Table 12-1

Table 12-1

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Dissociative Amnesia

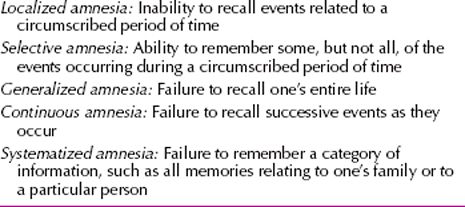

Table 12-2

Table 12-2

Types of Dissociative Amnesia

A 45-year-old, divorced, left-handed, male bus dispatcher was seen in psychiatric consultation on a medical unit. He had been admitted with an episode of chest discomfort, light-headedness, and left-arm weakness. He had a history of hypertension and had a medical admission in the past year for ischemic chest pain, although he had not suffered a myocardial infarction. Psychiatric consultation was called, because the patient complained of memory loss for the previous 12 years, behaving and responding to the environment as if it were 12 years previously (e.g., he did not recognize his 8-year-old son, insisted that he was unmarried, and denied recollection of current events, such as the name of the current president). Physical and laboratory findings were unchanged from the patient’s usual baseline. Brain computed tomography (CT) scan was normal.

On mental status examination, the patient displayed intact intellectual function but insisted that the date was 12 years earlier, denying recall of his entire subsequent personal history and of current events for the past 12 years. He was perplexed by the contradiction between his memory and current circumstances. The patient described a family history of brutal beatings and physical discipline. He was a decorated combat veteran, although he described amnestic episodes for some of his combat experiences. In the military, he had been a champion golden glove boxer noted for his powerful left hand.

He was educated about his disorder and given the suggestion that his memory could return as he could tolerate it, perhaps overnight during sleep or perhaps over a longer time. If this strategy was unsuccessful, hypnosis or an amobarbital (Amytal) interview was proposed. (Adapted from a case of Richard J. Loewenstein, M.D., and Frank W. Putnam, M.D.)

Epidemiology

Dissociative amnesia has been reported in a range of approximately 2 to 6 percent of the general population. No known difference is seen in incidence between men and women. Cases generally begin to be reported in late adolescence and adulthood. Dissociative amnesia can be especially difficult to assess in preadolescent children because of their more limited ability to describe subjective experience.

Etiology

In many cases of acute dissociative amnesia, the psychosocial environment out of which the amnesia develops is massively conflictual, with the patient experiencing intolerable emotions of shame, guilt, despair, rage, and desperation. These usually result from conflicts over unacceptable urges or impulses, such as intense sexual, suicidal, or violent compulsions. Traumatic experiences such as physical or sexual abuse can induce the disorder. In some cases the trauma is caused by a betrayal by a trusted, needed other (betrayal trauma). This betrayal is thought to influence the way in which the event is processed and remembered.

Diagnosis and Clinical Features

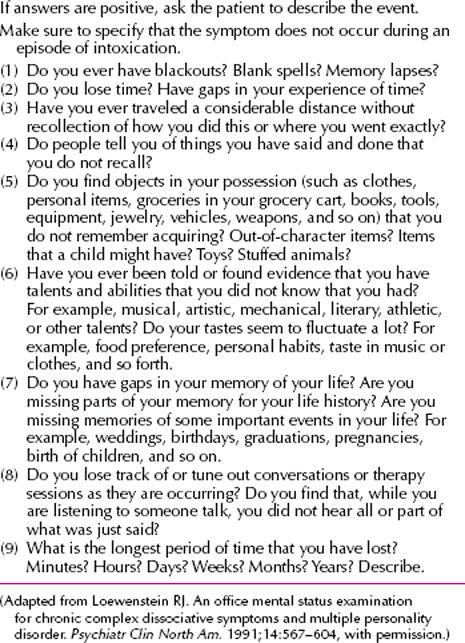

Classic Presentation. The classic disorder is an overt, florid, dramatic clinical disturbance that frequently results in the patient being brought quickly to medical attention, specifically for symptoms related to the dissociative disorder. It is frequently found in those who have experienced extreme acute trauma. It also commonly develops, however, in the context of profound intrapsychic conflict or emotional stress. Patients may present with intercurrent somatoform or conversion symptoms, alterations in consciousness, depersonalization, derealization, trance states, spontaneous age regression, and even ongoing anterograde dissociative amnesia. Depression and suicidal ideation are reported in many cases. No single personality profile or antecedent history is consistently reported in these patients, although a prior personal or family history of somatoform or dissociative symptoms has been shown to predispose individuals to develop acute amnesia during traumatic circumstances. Many of these patients have histories of prior adult or childhood abuse or trauma. In wartime cases, as in other forms of combat-related posttraumatic disorders, the most important variable in the development of dissociative symptoms, however, appears to be the intensity of combat. Table 12-3 presents the mental status evaluation of dissociative amnesia.

Table 12-3

Table 12-3

Mental Status Examination Questions for Dissociative Amnesia

Nonclassic Presentation. These patients frequently come to treatment for a variety of symptoms, such as depression or mood swings, substance abuse, sleep disturbances, somatoform symptoms, anxiety and panic, suicidal or self-mutilating impulses and acts, violent outbursts, eating problems, and interpersonal problems. Self-mutilation and violent behavior in these patients may also be accompanied by amnesia. Amnesia may also occur for flashbacks or behavioral re-experiencing episodes related to trauma.

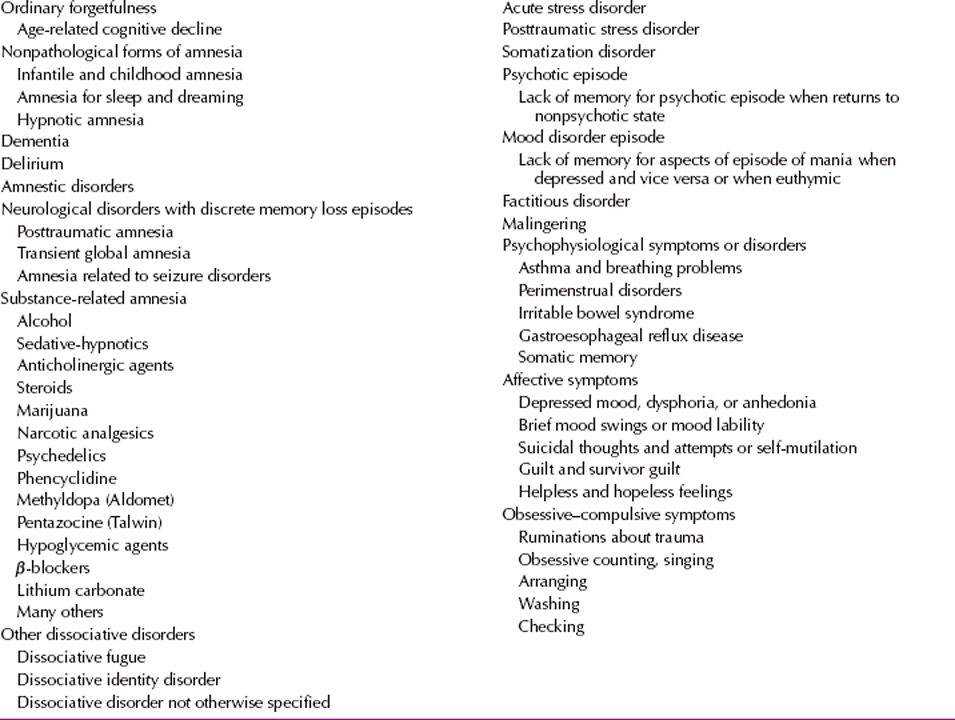

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of dissociative amnesia is listed in Table 12-4.

Table 12-4

Table 12-4

Differential Diagnosis of Dissociative Amnesia

Ordinary Forgetfulness and Nonpathological Amnesia. Ordinary forgetfulness is a phenomenon that is benign and unrelated to stressful events. In dissociative amnesia, the memory loss is more extensive than in nonpathological amnesia. Other nonpathological forms of amnesia have been described, such as infantile and childhood amnesia, amnesia for sleep and dreaming, and hypnotic amnesia.

Dementia, Delirium, and Amnestic Disorders due to Medical Conditions. In patients with dementia, delirium, and amnestic disorders due to medical conditions, the memory loss for personal information is embedded in a far more extensive set of cognitive, language, attentional, behavioral, and memory problems. Loss of memory for personal identity is usually not found without evidence of a marked disturbance in many domains of cognitive function. Causes of organic amnestic disorders include Korsakoff’s psychosis, cerebral vascular accident (CVA), postoperative amnesia, postinfectious amnesia, anoxic amnesia, and transient global amnesia. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may also cause a marked temporary amnesia, as well as persistent memory problems in some cases. Here, however, memory loss for autobiographical experience is unrelated to traumatic or overwhelming experiences and seems to involve many different types of personal experiences, most commonly those occurring just before or during the ECT treatments.

Posttraumatic Amnesia. In posttraumatic amnesia caused by brain injury, a history of a clear-cut physical trauma, a period of unconsciousness or amnesia, or both is usually seen, and there is objective clinical evidence of brain injury.

Seizure Disorders. In most seizure cases, the clinical presentation differs significantly from that of dissociative amnesia, with clear-cut ictal events and sequelae. Patients with pseudoepileptic seizures may also have dissociative symptoms, such as amnesia and an antecedent history of psychological trauma. Rarely, patients with recurrent, complex partial seizures present with ongoing bizarre behavior, memory problems, irritability, or violence, leading to a differential diagnostic puzzle. In some of these cases, the diagnosis can be clarified only by telemetry or ambulatory electroencephalographic (EEG) monitoring.

Substance-Related Amnesia. A variety of substances and intoxicants have been implicated in the production of amnesia. Common offending agents are listed in Table 12-4.

Transient Global Amnesia. Transient global amnesia can be mistaken for a dissociative amnesia, especially because stressful life events may precede either disorder. In transient global amnesia, however, there is the sudden onset of complete anterograde amnesia and learning abilities; pronounced retrograde amnesia; preservation of memory for personal identity; anxious awareness of memory loss with repeated, often perseverative, questioning; overall normal behavior; lack of gross neurological abnormalities in most cases; and rapid return of baseline cognitive function, with a persistent short retrograde amnesia. The patient usually is older than 50 years of age and shows risk factors for cerebrovascular disease, although epilepsy and migraine have been etiologically implicated in some cases.

Dissociative Identity Disorders. Patients with dissociative identity disorder can present with acute forms of amnesia and fugue episodes. These patients, however, are characterized by a plethora of symptoms, only some of which are usually found in patients with dissociative amnesia. With respect to amnesia, most patients with dissociative identity disorder and those with dissociative disorder not otherwise specified with dissociative identity disorder features report multiple forms of complex amnesia, including recurrent blackouts, fugues, unexplained possessions, and fluctuations in skills, habits, and knowledge.

Acute Stress Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Somatic Symptom Disorder. Most forms of dissociative amnesia are best conceptualized as part of a group of trauma spectrum disorders that includes acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and somatic symptom disorder. Many patients with dissociative amnesia meet full or partial diagnostic criteria for those acute stress disorders or a combination of the three. Amnesia is a criterion symptom of each of the latter disorders.

Malingering and Factitious Amnesia. No absolute way exists to differentiate dissociative amnesia from factitious or malingered amnesia. Malingerers have been noted to continue their deception even during hypnotically or barbiturate-facilitated interviews. A patient who presents to psychiatric attention seeking to recover repressed memories as a chief complaint most likely has a factitious disorder or has been subject to suggestive influences. Most of these individuals actually do not describe bona fide amnesia when carefully questioned, but are often insistent that they must have been abused in childhood to explain their unhappiness or life dysfunction.

Course and Prognosis

Little is known about the clinical course of dissociative amnesia. Acute dissociative amnesia frequently spontaneously resolves once the person is removed to safety from traumatic or overwhelming circumstances. At the other extreme, some patients do develop chronic forms of generalized, continuous, or severe localized amnesia and are profoundly disabled and require high levels of social support, such as nursing home placement or intensive family caretaking. Clinicians should try to restore patients’ lost memories to consciousness as soon as possible; otherwise, the repressed memory may form a nucleus in the unconscious mind around which future amnestic episodes may develop.

Treatment

Cognitive Therapy. Cognitive therapy may have specific benefits for individuals with trauma disorders. Identifying the specific cognitive distortions that are based in the trauma may provide an entrée into autobiographical memory for which the patient experiences amnesia. As the patient becomes able to correct cognitive distortions, particularly about the meaning of prior trauma, more detailed recall of traumatic events may occur.

Hypnosis. Hypnosis can be used in a number of different ways in the treatment of dissociative amnesia. In particular, hypnotic interventions can be used to contain, modulate, and titrate the intensity of symptoms; to facilitate controlled recall of dissociated memories; to provide support and ego strengthening for the patient; and, finally, to promote working through and integration of dissociated material.

In addition, the patient can be taught self-hypnosis to apply containment and calming techniques in his or her everyday life. Successful use of containment techniques, whether hypnotically facilitated or not, also increases the patient’s sense that he or she can more effectively be in control of alternations between intrusive symptoms and amnesia.

Somatic Therapies. No known pharmacotherapy exists for dissociative amnesia other than pharmacologically facilitated interviews. A variety of agents have been used for this purpose, including sodium amobarbital, thiopental (Pentothal), oral benzodiazepines, and amphetamines.

Pharmacologically facilitated interviews using intravenous amobarbital or diazepam (Valium) are used primarily in working with acute amnesias and conversion reactions, among other indications, in general hospital medical and psychiatric services. This procedure is also occasionally useful in refractory cases of chronic dissociative amnesia when patients are unresponsive to other interventions. The material uncovered in a pharmacologically facilitated interview needs to be processed by the patient in his or her usual conscious state.

Group Psychotherapy. Time-limited and longer-term group psychotherapies have been reported to be helpful for combat veterans with PTSD and for survivors of childhood abuse. During group sessions, patients may recover memories for which they have had amnesia. Supportive interventions by the group members or the group therapist, or both, may facilitate integration and mastery of the dissociated material.

DEPERSONALIZATION/DEREALIZATION DISORDER

Depersonalization is defined as the persistent or recurrent feeling of detachment or estrangement from one’s self. The individual may report feeling like an automaton or watching himself or herself in a movie (Fig. 12-1). Derealization is somewhat related and refers to feelings of unreality or of being detached from one’s environment. The patient may describe his or her perception of the outside world as lacking lucidity and emotional coloring, as though dreaming or dead (Fig. 12-2).

FIGURE 12-1Dissociative states are characterized by feelings of unreality, as evoked in this photograph. (Courtesy of Arthur Tress.)

FIGURE 12-2Depersonalization/derealization is experienced as a sense of unreality in one’s environment or sense of self, as evoked in this double-exposure photograph. (Courtesy of Hayley R. Weinberg.)

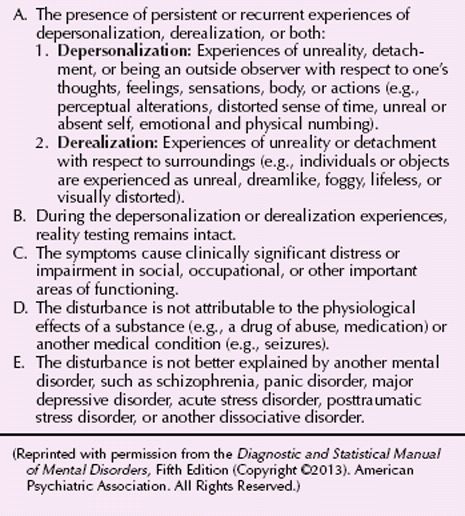

The current DSM-5 definition of depersonalization disorder is found in Table 12-5.

Table 12-5

Table 12-5

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder

Epidemiology

Transient experiences of depersonalization and derealization are extremely common in normal and clinical populations. They are the third most commonly reported psychiatric symptoms, after depression and anxiety. One survey found a 1-year prevalence of 19 percent in the general population. It is common in seizure patients and migraine sufferers; they can also occur with use of psychedelic drugs, especially marijuana, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and mescaline, and less frequently as a side effect of some medications, such as anticholinergic agents. They have been described after certain types of meditation, deep hypnosis, extended mirror or crystal gazing, and sensory deprivation experiences. They are also common after mild to moderate head injury, wherein little or no loss of consciousness occurs, but they are significantly less likely if unconsciousness lasts for more than 30 minutes. They are also common after life-threatening experiences, with or without serious bodily injury. Depersonalization is found two to four times more in women than in men.

Etiology

Psychodynamic. Traditional psychodynamic formulations have emphasized the disintegration of the ego or have viewed depersonalization as an affective response in defense of the ego. These explanations stress the role of overwhelming painful experiences or conflictual impulses as triggering events.

Traumatic Stress. A substantial proportion, typically one third to one half, of patients in clinical depersonalization case series report histories of significant trauma. Several studies of accident victims find as many as 60 percent of those with a life-threatening experience report at least transient depersonalization during the event or immediately thereafter. Military training studies find that symptoms of depersonalization and derealization are commonly evoked by stress and fatigue and are inversely related to performance.

Neurobiological Theories. The association of depersonalization with migraines and marijuana, its generally favorable response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and the increase in depersonalization symptoms seen with the depletion of L-tryptophan, a serotonin precursor, point to serotoninergic involvement. Depersonalization is the primary dissociative symptom elicited by the drug-challenge studies described in the section on neurobiological theories of dissociation. These studies strongly implicate the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) subtype of the glutamate receptor as central to the genesis of depersonalization symptoms.

Diagnosis and Clinical Features

A number of distinct components comprise the experience of depersonalization, including a sense of (1) bodily changes, (2) duality of self as observer and actor, (3) being cut off from others, and (4) being cut off from one’s own emotions. Patients experiencing depersonalization often have great difficulty expressing what they are feeling. Trying to express their subjective suffering with banal phrases, such as “I feel dead,” “Nothing seems real,” or “I’m standing outside of myself,” depersonalized patients may not adequately convey to the examiner the distress they experience. While complaining bitterly about how this is ruining their life, they may nonetheless appear remarkably undistressed.

Ms. R was a 27-year-old, unmarried, graduate student with a master’s degree in biology. She complained about intermittent episodes of “standing back,” usually associated with anxiety-provoking social situations. When asked about a recent episode, she described presenting in a seminar course. “All of a sudden, I was talking, but it didn’t feel like it was me talking. It was very disconcerting. I had this feeling, ‘who’s doing the talking?’ I felt like I was just watching someone else talk. Listening to words come out of my mouth, but I wasn’t saying them. It wasn’t me. It went on for a while. I was calm, even sort of peaceful. It was as if I was very far away. In the back of the room somewhere—just watching myself. But the person talking didn’t even seem like me really. It was like I was watching someone else.” The feeling lasted the rest of that day and persisted into the next, during which time it gradually dissipated. She thought that she remembered having similar experiences during high school, but was certain that they occurred at least once a year during college and graduate school.

As a child, Ms. R reported frequent intense anxiety from overhearing or witnessing the frequent violent arguments and periodic physical fights between her parents. In addition, the family was subject to many unpredictable dislocations and moves owing to the patient’s father’s intermittent difficulties with finances and employment. The patient’s anxieties did not abate when the parents divorced when she was a late adolescent. Her father moved away and had little further contact with her. Her relationship with her mother became increasingly angry, critical, and contentious. She was unsure if she experienced depersonalization during childhood while listening to her parents’ fights. (Adapted from a case of Richard J. Loewenstein, M.D., and Frank W. Putnam, M.D.)

Differential Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree