22

22

Does Following the Recommendations in the Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Make a Difference in Patient Outcome?

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

—Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

BRIEF ANSWER

Because of the relatively meager scientific evidence supporting the individual recommendations in the Guidelines, one would not expect protocols based on the Guidelines to have a significant effect on patient outcome. However, several studies demonstrate that the possibility of significant improvement in outcome does exist. Reduction in mortality as seen in one of the three reported studies may be related to detailed and comprehensive management protocols for intracranial hypertension and cerebral perfusion. Data on hospital costs are difficult to interpret because authors use different methods to generate the published numbers. Clinical pathways that focus on the organizational management of patient care, as in the study by Vitaz et al (discussed below), see a significant reduction in costs, whereas Palmer et al (discussed below) advocate very intensive patient management with expensive monitoring technology that entailed higher costs. Higher costs in the acute care setting, however, can result in significant cost reductions later on if overall outcome is improved.

Pearl

Although Guidelines-based treatment protocols may raise acute care costs in institutions that previously had not practiced aggressive treatment or sophisticated monitoring of brain-injured patients, overall improvement in patient outcomes may offset the initially increased costs.

Background

Patient management guidelines document the current scientific basis of clinical practice. In keeping with Wittgenstein’s above statement from 1918, the guidelines explicitly state and emphasize what can be discussed based on scientific evidence, and they avoid recommendations that are based only on expert opinion. Their ultimate purpose is to improve and standardize delivery of care and to stimulate research that will not only identify superior treatment modalities, but also improve the methods of clinical research.

The guideline movement in neurosurgery first attracted attention in 1995 when the Guidelines for the Management of Severe Head Injury were published as a joint effort of the Brain Trauma Foundation, the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, and the Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. An update was published in 2000 as Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (Guidelines).1 The Guidelines consisted of 14 topics ranging from trauma systems and prehospital resuscitation to monitoring and treatment of intracranial hypertension and other related topics. Since then, the Guidelines have been adopted by neurosurgeons around the world. A Medline search reveals a multitude of articles that deal with implementation of the Guidelines into clinical practice. The frequency with which the Guidelines are cited in the literature suggests that they have had a significant impact on how patients with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) are treated.

It is important to understand that guidelines per se are not a practical clinical tool, but rather a summary and review of scientific evidence. They have to be part of a more comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment protocol that embraces all aspects of patient care, including geographic and infrastructure-related characteristics of a particular trauma center. This chapter reviews the literature that explores whether or not treatment protocols for severe TBI based on the Guidelines make a difference in patient outcome.

Literature Review

Only three of the Guidelines’ recommendations (about hyperventilation, steroids, and anticonvulsants) are based on prospective, randomized, controlled trials that demonstrated a significant effect (or lack thereof) on patient outcome; that is, they are based on class I evidence that can support a ” standard.“

Hyperventilation in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury

The recommendation that ” in the absence of increased intracranial pressure (ICP), chronic prolonged hyperventilation therapy should be avoided after severe TBI“ is based on a prospective study by Muizelaar et al.2 In their study, 77 patients with severe TBI were randomized to a group treated with chronic prophylactic hyperventilation for 5 days or to a group that was kept normocapneic during that time. Six months after trauma, patients with an initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) motor score of 4 to 5 who had been hyperventilated had a significantly worse outcome.

Steroids for the Treatment of Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury

The use of steroids is not recommended for improving outcome or reducing ICP in patients with severe TBI. This standard was based on nine class I trials in which the preponderance of evidence demonstrated that steroids did not reduce ICP or improve outcome after TBI. The largest study was published in 1994 by Gaab et al.3 The authors conducted a randomized, prospective, double-blind, multicenter trial investigating the efficacy and safety of very high dose dexamethasone on outcome in 300 patients with moderate and severe TBI. At 12 months, no differences were found between the treatment groups.

Antiseizure Medication in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury

Antiseizure prophylaxis is not recommended for the prevention of late posttraumatic seizures. This recommendation is supported by eight class I studies. The largest of these is a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 404 patients published by Temkin et al.4 Patients were randomized to a group treated with phenytoin or to a group that received placebo. The incidence of early posttraumatic seizures, that is, those occurring during the first week after injury, was significantly lower in the treated group. No effect was seen on the occurrence of late posttraumatic seizures, and survival was the same in both groups.

Clinical Protocols Based on the Guidelines

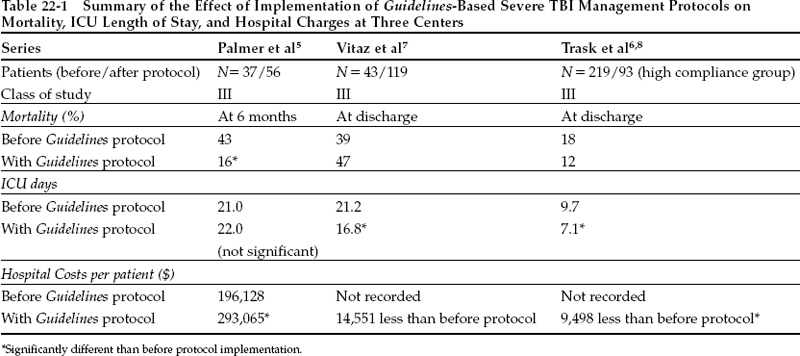

Three class III studies have addressed the impact of Guidelines-based protocols on patient management. Their main results are summarized in Table 22–1.

Palmer et al5 compared outcomes from the 42-month period preceding implementation of a Guidelines-based TBI protocol (37 patients) to those from the 30-month period after implementation of the protocol (56 patients). Patients age 8 years or older with a closed head injury and GCS score of 3 to 8 or patients who deteriorated to that level within 48 hours of admission were included. Data from the 37 preimplementation patients were obtained retrospectively, whereas concurrent data collection was performed on the 56 postimplementation patients. The initial treatment protocol emphasized fluid restriction, hyperventilation to a PaCO2 between 25 and 30 mmHg, liberal use of vasopressors to keep systolic blood pressure above 90 mmHg, and treatment of ICP >20 mmHg with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage and mannitol. No minimum target for cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) was specified. In contrast, the Guidelines-based protocol emphasized fluid resuscitation, hemodynamic monitoring with continuous cardiac output pulmonary artery catheters, and jugular bulb oximetry in addition to ICP monitoring. Specific treatment goals included maintenance of the following physiologic parameters: CPP >70 mmHg, ICP <20 mmHg, central venous pressure 5 to 10 mmHg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 10 to 15 mmHg, jugular venous oxygen saturation 55 to 75%, SaO2 >95%, PaCO2 35 mmHg, and aggressive, early nutritional support.

The protocol covered patient care in the emergency room, in the operating room, and in the intensive care unit (ICU). Age, admission GCS score, length of stay in the ICU, and total number of ventilator days were not different between groups. Score on the dichotomized Glasgow Outcome Scale at 6 months was significantly better in patients treated with the protocol. The proportion of deaths decreased by more than 50%, and the proportion of patients with good outcomes more than doubled. Hospital costs, however, were more than $97,000 higher in patients treated according to the Guidelines. This result was attributed mainly to the use of more expensive drugs (e.g., propofol) and monitoring technology (jugular bulb oximetry, fiberoptic ICP monitors, etc.). The authors speculated that higher hospital costs may be more than compensated for by improved patient outcomes, with reduced need for rehabilitation and quicker reintegration into society.

Pearl