28

28

Does Hypothermia Improve Outcome?

BRIEF ANSWER

Maintenance of hypothermia in the 23% of severely head-injured patients who are hypothermic on admission and who are less than 45 years of age may improve outcome. It is possible that very early induction of hypothermia (<3 hours after injury) may improve outcome.

Background

In 1993, phase II studies testing surface cooling in patients with severe brain injuries were completed in Houston1 and Pittsburgh2 (class I data). These trials were based on laboratory data in brain injury and were supported by an extensive experimental literature in stroke, as well as by a phase I safety trial (class II data).3,4 The Houston cooling protocol achieved 33°C within 8 hours of injury and maintained hypothermia for 48 hours, resulting in a 15% absolute improvement in the percentage of patients with good outcome [good recovery/moderate disability on the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS)]. The Pittsburgh hypothermia protocol achieved 33°C within 10 hours after injury and used a 24-hour period of hypothermia. A 24% absolute improvement in the percentage of patients with good outcome was found in this study. No significant hypothermia-related toxicity occurred in either study. Based on the strength of the Houston and Pittsburgh studies, the National Acute Brain Injury Study: Hypothermia (NABIS:H) was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) in 1994.

Clinical Trial and Literature Review

The specific aim of NABIS:H, a randomized, prospective, multicenter trail, was to determine if surface-induced moderate hypothermia (33°C) begun within 6 hours of severe brain injury [Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score <8) and maintained for 48 hours would improve outcome, with low toxicity. The design of NABIS:H projected that an enrollment of 500 patients would be needed to detect a 10% absolute shift in the percentage of patients making a good outcome on the GOS score (good outcome = good recovery or moderate disability; poor outcome = severe disability, vegetative, or dead) at 6 months after injury. NABIS:H met its performance standards, but after enrolling 392 patients, the trial was stopped in May 1998 by the Patient Safety and Monitoring Board when a regularly scheduled futility analysis showed low probability of detecting a treatment effect (class I data).5

There was no difference in outcome measured at 6 months postinjury, with 57% of both groups showing a poor outcome.5 The mortality rate was 28% in the hypothermia group and 27% in the normothermia group. Data analysis showed that treatment with hypothermia blunted major elevations of intracranial pressure (ICP), with a significantly lower percentage of hypothermia patients having ICP >30 mmHg (hypothermia group 41%, normothermia group 59%; p <.02). Older patients (age >45 years, n = 52) had a higher percentage of poor outcomes than younger patients (hypothermia 88%, normothermia 69%; p = .08).

Patients were randomized at 4.2±1.1 hours after injury; those assigned to hypothermia reached 33°C at 8.4±3.1 hours after injury. There were no significant differences between the groups in age, admission GCS score, incidence of operated hematomas, subarachnoid hemorrhage, prehospital hypoxia, computed tomography (CT) classification or Injury Severity Score. The hypothermia treatment group had a higher cumulative fluid balance (intake output) for the first 96 hours (hypothermia 3061 5946 mL, normothermia 1947±4586 mL, p<.05). Patients treated with hypothermia also received vasopressors for a higher percentage of the first 96 hours (hypothermia 48.5 33.9%, normothermia 41.0±37.8%, p<.05). This was anticipated in the trial design because volume expansion and vasopressors are often required during rewarming. All other aspects of management were similar in the two treatment groups.

Pearl

Outcome did not differ between normothermia and hypothermia groups, but hypothermia blunted major elevations of intracranial pressure.

Pearl

Volume expansion and vasopressors are often required during rewarming.

The hypothermia group had a higher percentage of hospitalization days with complications (hypothermia 78%±22% days, normothermia 70%±29% days, p <.005). Hypotension for two or more consecutive hours with organ failure recorded as a complication occurred in 10% of hypothermia patients and 3% of normothermia patients (p = .01). Ventricular arrhythmias occurred in 22 hypothermia patients and 19 normothermia patients. Mean ICP did not differ in the two treatment groups. The percentage of patients with ICP >30 mmHg in the hypothermia group was 41%, as compared with 59% in the normothermia group (p = .02). Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) levels were similar in both groups. The percentage of patients with occurrence of MAP <70 mmHg and CPP <50, <60, or <70 mmHg was the same in both treatment groups. There were no clinically significant differences in electrolyte balance between hypothermia and normothermia groups. Potassium levels in the groups differed by 0.1 mEq. Mean serum sodium values differed by 1 mEq. Mean serum glucose was 155 mg/dL in hypothermia patients and 151 mg/dL in normothermia patients.

Subgroup Analyses

We conducted subgroup analyses on variables known to influence outcome from severe brain injury, including age, initial GCS score, pupillary reactivity, presence of surgical mass lesions, hypoxia, hypotension, and initial CT classification. We also examined the effect of hypothermia treatment on those who were hypothermic on admission. In addition, the effects of the amount of time between injury and attainment of the target temperature of 33°C were examined.

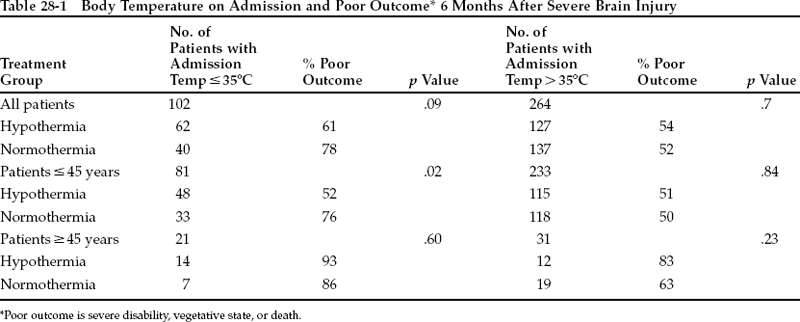

Age and admission temperature were the only two variables that exerted a significant effect.5 Patients age ≥45 years had a higher percentage of poor outcomes (hypothermia 88% poor outcome, normothermia 69% poor outcome, p = .08). This was most likely due to a higher percentage of hospital days with medical complications in the hypothermia group (hypothermia 82%±21%, normothermia 55%±29%, p = .002) (Table 28-1).

Twenty-eight percent of the NABIS:H patients had body temperatures <35°C as their first recorded temperature after arrival in the emergency department. In this subgroup, the percentage of patients with poor outcome was 78% for those patients assigned to normothermia. The percentage of patients with poor outcome was 61% in the group treated with hypothermia (p =.09), an absolute improvement of 17%. Patients older than 45 years were adversely affected by induction or maintenance of hypothermia regardless of admission temperature. Among patients aged 16 to 45 years, the hypothermia treatment effect was, therefore, even more pronounced, with a percentage of poor outcomes of 52% for patients assigned to hypothermia compared with 76% for patients assigned to normothermia (p =.02), an absolute improvement of 24%. In this subgroup there was no difference in percentage of hospital days with complications (hypothermia 78.9%±20%, normothermia 78.6%±25%; not significant). This treatment effect of maintaining hypothermia was found in patients at all temperatures below 35°C. The apparent benefit of maintaining hypothermia in those who were hypothermic on admission raises the question of what the treatment window for neuroprotective hypothermia might be. However, there are not sufficient data at this time to make a recommendation on the hypothermic treatment window for patients who are hypothermic on admission.

Pearl