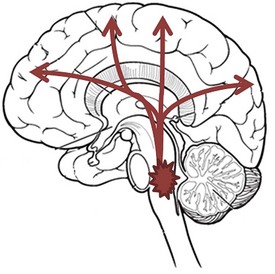

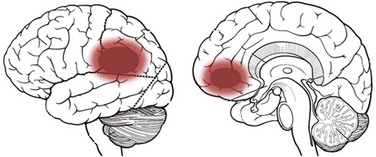

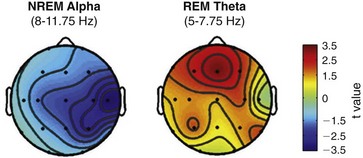

Chapter 7 After the discovery of REMS in the 1950s, it was widely presumed that this pseudo-awake and paradoxically “active” brain state during sleep must represent the biologic basis of dreaming. Subsequent neurobiologic theories of dream generation, such as Hobson and McCarley’s influential activation synthesis hypothesis, strongly emphasized the role of cholinergic brainstem activity during REMS (Fig. 7-1).1 Unquestionably, relative to NREMS, recall of dreaming is more probable when participants are awakened from REMS. However, it later became clear that mental experiences can be recalled from all stages of sleep,2 including even the deepest stages of slow-wave sleep (SWS), suggesting that a more inclusive theory of dreaming is required. Mark Solms’ work with patients who report loss of dreaming after brain injury provides clues to a possible REM-independent mechanism of dream generation. Solms has argued that although REMS physiology is not necessary to dreaming, particular forebrain structures are critical for dream generation to occur. According to his observations, damage to brainstem regions involved in REMS spares dreaming, but patients with forebrain lesions near the parieto-temporo-occipital junction or ventral medial prefrontal cortex often report a complete cessation of dream experience (Fig. 7-2).3 Activity in these forebrain structures may possibly be a necessary condition for the generation and recall of dreams experience in both REMS and NREMS. Figure 7-1 Allan Hobson’s activation synthesis theory of dream generation. Figure 7-2 Brain lesions that lead to loss of dreaming. Moving into the future, research on the brain basis of dream generation will likely continue to focus on mechanisms common to both types of sleep. Recently, several studies using high-density recording have begun to describe within-stage electroencephalogram dynamics that may support dream recall. For example, Marzano and colleagues4 recently reported that the recall of dreaming during REMS is associated with an increase in frontal theta-wave frequency oscillations, whereas the recall of dreaming from NREMS is associated with decreased alpha-wave activity over right temporal regions (Fig. 7-3). Because these electroencephalographic correlates of dream recall overlap with those that herald successful memory retrieval during wakefulness, the formation and recall of memory in wake and sleep states may share a common neural substrate. Figure 7-3 Electroencephalogram (EEG) correlates of dream recall during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-REM (NREM) sleep.

Dreaming in Normal and Disrupted Sleep

What is Dreaming?

Brain Basis of Dream Experience

First proposed in the 1970s by Hobson and McCarley, this highly influential model of dreaming was revolutionary in its ambition to explain dreaming as a neurobiologic phenomenon rather than a psychologic mechanism. According to the activation synthesis hypothesis, dreaming originates as a series of random impulses in cholinergic regions of the pons and midbrain. This cholinergic brainstem input then activates diffuse regions of the cortex during rapid eye movement sleep, where the chaotic bottom-up input is “synthesized” into a relatively more coherent narrative, with the result being a dream.

Neuropsychologist Mark Solms has described a number of cases in which patients report loss of dreaming after damage to the parieto-temporo-occipital junction (left) or ventromedial prefrontal cortex (right). Because rapid eye movement (REM) sleep remained intact in these patients, and because damage to the pontine brainstem has not similarly been reported to result in impaired dreaming, Solms concludes that the generation of dreaming relies more fundamentally on these forebrain regions then on REM-related brainstem structures.

Examining sleep EEG spatial and frequency characteristics before morning awakening, Marzano and colleagues found that the recall of dreaming was associated with a decrease in right temporal alpha-wave activity during NREM sleep (left) and with increased frontal theta-wave activity during REM sleep (right).![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Dreaming in Normal and Disrupted Sleep

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue