- Many classes of drug, whether prescribed or recreational, are taken with the specific aim of influencing the sleep-wake cycle

- The formal evidence base for the pharmacological treatment of the majority of sleep disorders is very limited and many drugs are used empirically

- Caffeine, modafinil and amphetamine-like agents are the most commonly used agents for promoting wakefulness, often in combination

- Clear protocols for the drug treatment of chronic insomnia are lacking and long-term courses of hypnotic agents are generally discouraged through fears of dependence and tolerance

- If an agent is used to aid sleep, its pharmacokinetic profile should be appropriately matched for the type of insomnia

- Many drugs such as benzodiazepines and the majority of anti-depressants will produce drowsiness but often fail to improve the quality of any sleep obtained

- It is relatively rare for hypnotic or sedative drugs to increase or enhance the deeper stages of non-REM (slow wave) sleep

Whether obtained by a prescription, over the counter or illegally, one of the commonest reasons for a person to take a drug is to influence the sleep–wake cycle. Typically, the elderly seek agents to improve their nocturnal sleep whereas younger age groups want to stay more awake.

Unfortunately, the evidence base for pharmacological treatment of the vast majority of sleep disorders remains sparse. As a result, drugs are often chosen either empirically or from anecdotal evidence and personal experience. Furthermore, given that most trial data are generated from short-term studies, little guidance exists on the appropriate length of treatment courses.

Only a minority of drugs are formally licensed for a sleep-related indication. In addition, because sleep medicine remains a relatively new discipline, familiarity with many of these agents is low. A further reason for reduced confidence in prescribing drugs for sleep disorders is that many general physicians might feel that a certain sleep-related symptom reflects lifestyle choices more than a purely medical problem.

Agents to promote wakefulness

The vast majority of subjects with a significant primary sleep disorder such as narcolepsy will benefit from drug therapy to improve alertness. In some other clinical situations where daytime somnolence remains severe despite first-line therapy, it may also be appropriate to recommend wake-promoting agents. The use of traditional psychostimulant drugs such as amphetamine has declined largely through concerns over dependency and the relatively non-specific mode of action.

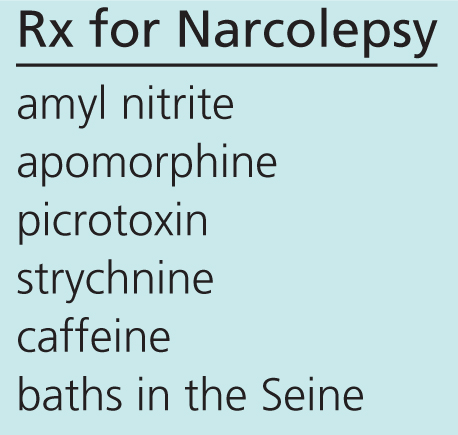

The earliest treatments for narcolepsy when it was first described by French neuropsychiatrists in the late nineteenth century almost certainly would have kept subjects awake (Figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1 A ‘recipe’ outlining a treatment plan for narcolepsy described by Dr Gelineau, a Parisian neuropsychiatrist who first devised the term ‘narcolepsy’.

Caffeine

Caffeine is clearly widely available in a vast variety of drinks and also tablet form. However, it can often be difficult to judge precise doses consumed; these typically vary between 50 and 200 mg. The main relevant pharmacological action of caffeine is to inhibit adenosine (A1) receptors in the basal forebrain. This is thought to oppose the natural sleep drive, which arises partly from increasing adenosine levels in the brain after prolonged wakefulness. There is a wide variation between individuals both in the alerting response to caffeine and the likelihood of adverse effects such as insomnia.

Although a relatively mild wake-promoting agent for most, caffeine is probably under-used as a supplement in sleep disorders that cause significant somnolence. At the very least, it can usefully improve vigilance in sleep-deprived subjects.

Modafinil

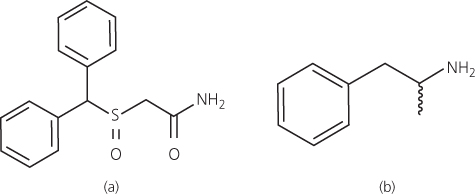

Modafinil was first introduced as a unique wake-promoting drug in the 1980s after the serendipitous discovery that it kept cats awake for prolonged periods in experimental drug studies assessing depression. The new drug was noted to have a different chemical structure to traditional psychostimulant agents such as amphetamine (Figure 11.2). Its precise mode of action remains unclear although it appears to activate the ‘wake’ nuclei in the hypothalamus fairly specifically. Unlike amphetamine, it does not produce euphoria. Furthermore, tolerance after prolonged use is usually minimal. The half-life is quite long (10–15 hours) such that typical doses (100 or 200 mg) are taken shortly after awakening and at lunchtime to avoid insomnia at night.

Although modafinil is formally licensed in many countries only for the treatment of primary sleep disorders such as narcolepsy, many clinicians recommend its use in other situations. Excessive sleepiness associated with head injuries or other neurological disorders often benefit from the drug, as do patients with severe obstructive sleep apnoea who remain sleepy despite optimal therapy with a positive airways pressure mask. Furthermore, it is occasionally appropriate to prescribe the drug before a night shift at work if other countermeasures to improve drowsiness have failed.

Some claim that modafinil is effective as a cognitive enhancer or ‘smart drug’. Although it remains unclear whether it improves attention and performance in those who are not sleepy, it is sometimes misused in student populations, for example, in attempts to boost academic achievement.

The more common side effects of modafinil include headache and gastrointestinal upset. It does not have the same stimulatory effects on the cardiovascular system as more traditional stimulants but blood pressure can rise slightly and should be monitored. Woman of child-bearing age should be told that modafinil is known to induce liver enzymes and has the potential of rendering standard oral contraceptive therapy ineffective.

Amphetamine and related drugs

Amphetamines and drugs such as methylphenidate have a very similar mode of action and are generally only used as second-line agents in primary sleep disorders causing hypersomnolence. Amphetamine is most commonly used as a supplement to modafinil or as an alternative if there are side effects. It is given in low doses (typically 5 mg up to five times a day) and usually taken flexibly. A single dose typically gives up to two hours of increased alertness at levels roughly equivalent to the wake-promoting effects of drinking around six cups of coffee.

At low doses, amphetamine and similar drugs promote the release of dopamine and noradrenaline from nerve terminals and inhibit their reuptake. As a result, the pharmacological effects are not limited to increased wakefulness. Agitation or palpitations may occur as unwanted side effects.

Amphetamine will generally suppress appetite and worsen hypertension, which may also limit its usefulness. The euphoric effects seem less pronounced when used in conditions such as narcolepsy. Indeed, frank abuse in very rarely seen in this clinical population.

Selegiline

Selegiline was first introduced in the 1950s as a dog food additive to give pets a ‘boost’. It is metabolised in the liver to amphetamine, making it useful as a mild psychostimulant in addition to its more familiar role as an agent to improve the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Although not licensed as a wake-promoting drug, it is sometimes recommended as an alternative to amphetamine in elderly patients or those not suitable for more powerful drugs. Doses higher than those used in Parkinson’s disease (more than 20 mg daily) seem to be safe in narcoleptics, for example.

Mazindol

Mazindol was first developed as an appetite suppressant but found early promise as a psychostimulant in narcoleptic patients. It’s mode of action remains obscure although the clinical effects resemble those of amphetamine. It is sometimes used as an unlicensed alternative agent for narcolepsy with cataplexy in those resistant or intolerant to conventional therapy.

Side effects include nausea and agitation. Concerns over a possible theoretical risk of pulmonary hypertension with long-term use have necessitated specialist use only.

Agents to induce or improve nocturnal sleep

General principles

Although hypnotics are amongst the most commonly used class of drugs, prescribing guidelines and protocols are poorly developed. In the last decade there has been increasing reluctance to recommend hypnotics, largely through fears of dependence, tolerance and morning side effects. In patients with severe and chronic symptoms, the poor availability of behavioural or other non-pharmacological therapies, leads to understandable frustration and anxiety, potentially fuelling worsening insomnia and an increased demand for a pharmacological approach.

Many patients with chronic insomnia have tried numerous strategies before seeking medical help. Antihistamines available over-the-counter or herbal remedies such as lavender are rarely of major benefit. Similarly, for obvious reasons, excess alcohol should be discouraged if used primarily as an aid to achieve sleep onset.

Wherever possible, a treatable cause for insomnia should be addressed. Restless legs syndrome causing significant sleep onset problems and obstructive sleep apnoea producing unrefreshing sleep are common examples of missed diagnoses.

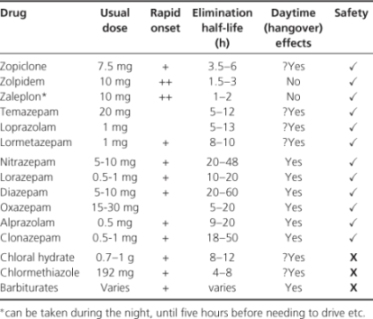

If hypnotic drug therapy is considered appropriate, the nature of the insomnia should be determined. A drug’s absorption and elimination properties should match the profile of insomnia. Short-acting drugs should be reserved for problems actually falling asleep and longer-acting agents if sleep interruption late in the night is the major concern (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1 Properties of commonly used hypnotic agents.