CHAPTER 25 Dural Sinus Invasion in Meningiomas and Repair

INTRODUCTION

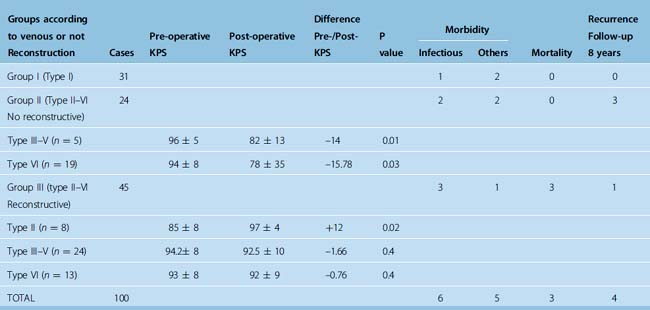

Surgery of meningiomas involving the major dural sinuses leaves the surgeon confronted with a difficult dilemma: leave the fragment invading the sinus in place and have a higher risk of recurrence, or attempt a total removal and expose the patient to a greater operative danger. The controversy of what constitutes the best treatment is still in debate.1 Some claim that leaving the intraluminal fragment in place is the best treatment, and others that attempt at total gross removal with venous reconstruction is preferable. The latter is our preference, based on a 20-year experience corresponding to a series of 100 meningiomas that were studied and then reported in 2006.2 The effects, in terms of recurrence rate and morbidity and mortality, of attempting complete removal including the invaded portion of the dural sinus, and in addition the consequences of restoring or not the venous circulation were studied. Our series consisted of 100 consecutive patients who underwent surgery between January 1980 and January 2001 (Table 25-1). Meningiomas originated at the superior sagittal sinus in 92 of the cases (28 in the anterior, 48 in the middle and 16 in the posterior third), the transverse sinus in 5, and the confluence of sinus in 3. A simplified classification scheme based on the degree of dural sinus involvement was applied:

Gross tumor removal was achieved in 93% of the cases and reconstruction of the sinus was attempted in 45 (65%) of the 69 cases with wall and lumen invasion. The overall recurrence rate in the study was 4%, with a follow-up ranging from 3 to 23 years (mean 8 years). The mortality rate was 3%, all cases due to brain swelling after en bloc resection of a type VI meningioma without venous restoration. Eight patients who harbored a lesion in the middle third portion of the superior sagittal sinus had permanent neurologic aggravation, likely due to local venous infarction. Six of these patients had not undergone a venous repair procedure. Venous reconstruction did not increase the morbidity–mortality rate in our series. From this study we concluded the following: (1) the relatively low recurrence (4%) favors attempts at complete removal, including the portion invading the sinus; (2) because the subgroup of patients without venous reconstruction displayed statistically significant clinical deterioration after surgery compared with the other subgroups (P = 0.02), venous flow restoration seems justified when not too risky.2

CLASSIFICATION OF SINUS INVASION

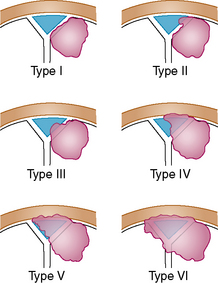

Different classifications of sinus invasion have been proposed by different authors, especially Krause (quoted by Merrem3) and Bonnal and Brotchi.4–7 For surgical purpose, we developed a simplified classification that we believe is easy to remember. This classification, developed for the sagittal sinus location shown in Figure 25-1, may also be applied to meningiomas involving the torcular and the transverse sinus.2

PREOPERATIVE INVESTIGATIONS

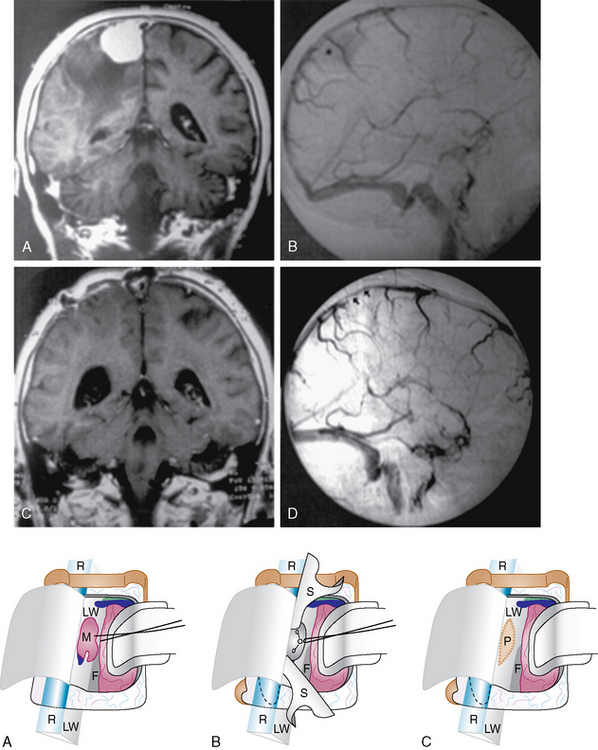

Selective bilateral internal and external carotid subtraction angiographies as well as vertebral angiography serve to determine the dural and cortical–pial supply ipsilateral or contralateral to the tumor. The arterial phase is useful to predict the difficulty of dissection of the capsule from the cortex. As we have shown in prior publications, dissection entails neurologic risk when a pial vascular supply is identified.8 When meningeal supply is important, preoperative embolization may be of some value in producing tumor necrosis and decreasing the operative risks to the patient by diminishing the blood loss that accompanies resection of these tumors.

The late venous phases with bilateral filling of the sagittal sinus are required for the exact evaluation of sinus patency and collateral venous pathways. Oblique views can depict the superior sagittal sinus (SSS) throughout its entire course. Various degrees of sinus occlusion can be observed from simple compression with narrowing of the sinus lumen to intraluminal defect to total occlusion. Complete occlusion may be assumed from no visualization of segments of the sinus and from collateral venous channel development. The pattern of venous drainage and venous collateral channels must be established preoperatively to determine the surgical approach (Fig. 25-2).

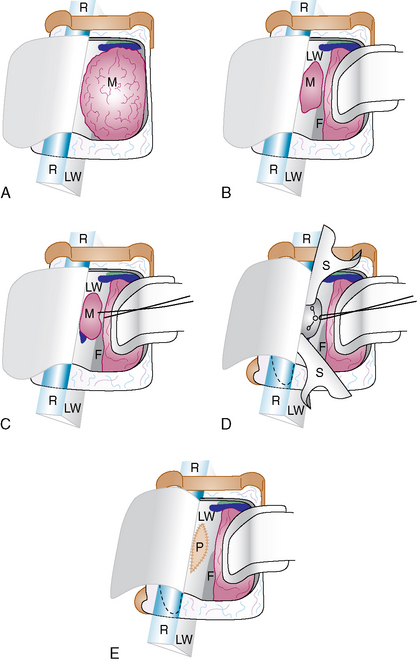

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

General Principles

Exposure and initial steps

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree