Dural Sinus Occlusive Disease

Key Points

Dural sinus stenotic disease may be a common cause of benign intracranial hypertension and idiopathic headache. Endovascular treatment for this condition may play a greater role in the future.

Dural sinus thrombotic disease might be amenable to endovascular therapy in some patients, but the efficacy or outcome of this treatment has not been established.

Formerly, neurointerventionalists were familiar with venous navigation of the dural sinuses only in the course of transvenous embolization of dural arteriovenous malformations. In the past few years, however, endovascular technology has lent itself to potentially helpful procedures for the treatment of idiopathic venous hypertension and acute dural sinus thrombosis (DST).

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) (“pseudotumor cerebri,” “benign intracranial hypertension”) is a condition characterized by elevation of intracranial pressure in the absence of a mass-occupying lesion or hydrocephalus, and with normal CSF composition (1). The cause of this condition is not known. It may be related to a disruption of CSF dynamics, and it is characteristically a disease of overweight young females of childbearing age.

The symptoms of this disorder are typically severe headache of prolonged duration, transient or permanent visual disturbances of various types, pulse synchronous tinnitus, retrobulbar pain, and double vision (2). This group of headache patients is set apart from other nonspecific headache patients by the ophthalmologic finding of papilledema, which generally leads to performance of a lumbar puncture, identification of elevated CSF pressure (>200 mm H2O in nonobese patients, >250 mm H2O in obese patients), and establishment of the diagnosis. There is some evidence and speculation that this disorder may be more common than hitherto suspected by virtue of the observation that a substantial proportion of IIH patients, probably those with milder pressures, may not demonstrate papilledema (3,4), and that this condition could account for as many as 25% of chronic headache patients.

Most patients respond well to treatment with weight loss, serial lumbar punctures, and pharmacologic therapy with acetazolamide, topiramate, or furosemide, but about 20% of patients are refractory to conventional treatments (5,6). About 3% to 10% develop serious visual complications, and 25% develop milder but significant visual impairment, from prolonged disruption of axonal transport and ischemic complications in the optic nerves (7,8,9). As many as 50% of cases of “fulminant” IIH lose substantial vision to the point of permanent legal blindness. A variety of CSF-diverting procedures including lumboperitoneal shunting and optic nerve fenestration have been demonstrated to be effective for some patients, and have become the established treatment when medical therapy has failed.

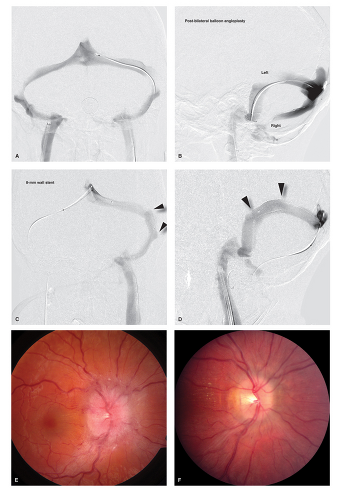

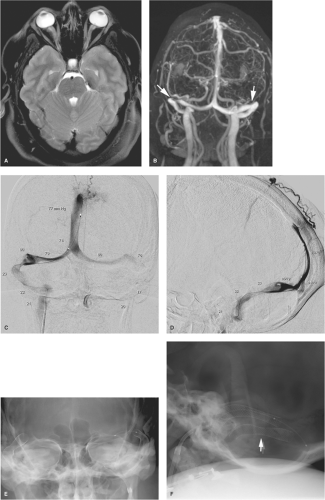

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is one of those disorders that, depending on its manifestations and complications, can show up in clinics of varying specialties and, accordingly, evokes different anecdotal biases and perspectives when treatment is discussed. In the past decade several case series (10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17) have been published advocating endovascular treatment, specifically stenting of the transverse sinuses, as a potential therapy for selected patients with refractory IIH, but it has not yet been generally embraced and has not been ratified by any type of randomized trial (Figs. 29-1–29-3).

The core issue is the pathophysiology of the disease, which is not understood. Approximately 90% of patients with IIH demonstrate evidence of narrowing, compression, or stenosis of the transverse sinuses on gadolinium-enhanced MRV. This area is typically prone to artifact on time-of-flight MRV, and thus many radiologists are accustomed to seeing “narrowing” in this particular area and dismissing the finding as normal variation or in-plane artifact. The sensitivity of gadolinium-enhanced MRV has changed this standard. The narrowing of the sinuses and the localization of a pressure gradient to that site is consistently seen on subsequent venography in patients with IIH. The debate and controversy surrounding endovascular therapy for IIH depends on one’s interpretation of these findings.

If the narrowing of the transverse sinuses in patients with IHH is epiphenomenal and a consequence of the elevated ICP, then insertion of a stent to prop open the sinus should not reverse the disease. Moreover, it is well recognized in some patients that medical therapy or shunting procedures can improve the disease and cause normalization of the appearance of the transverse sinus (18,19). On the other hand, however, it is possible and cogent that the compression

of the dural sinuses might be effectively a positive feedback mechanism of self-sustaining pathophysiology, the interruption of which might explain why a substantial number of severely affected patients have a remarkable and sustained improvement of their symptoms with a transvenous stenting procedure. Due to the success of the published case series and the dire consequences of permanent visual loss in the most fulminant of cases of IIH, usually having already demonstrated a nonresponsiveness to medical therapy, it is likely that transvenous stenting of this condition will see a surge in practice in the future.

of the dural sinuses might be effectively a positive feedback mechanism of self-sustaining pathophysiology, the interruption of which might explain why a substantial number of severely affected patients have a remarkable and sustained improvement of their symptoms with a transvenous stenting procedure. Due to the success of the published case series and the dire consequences of permanent visual loss in the most fulminant of cases of IIH, usually having already demonstrated a nonresponsiveness to medical therapy, it is likely that transvenous stenting of this condition will see a surge in practice in the future.

Figure 29-2. (A–F) Idiopathic intracranial hypertension treated with emergency endovascular stenting. This young female presented with precipitate loss of vision and severe headache. Her MRI (A) showed prominent bulging of the optic discs and redundancy of the optic sheaths. The gadolinium-enhanced venogram (B) demonstrates bilateral narrowing of the transverse sinuses (arrows) although the appearance is not impressive and the finding on the left has to be sought diligently on different projections in order to be seen. The retrograde venogram (C and D) also shows that the venous compression/narrowing tends not to be a visually dramatic finding. Transvenous pressure readings are annotated indicating a venous gradient of greater than 50 mm Hg bilaterally at the midtransverse sinus. Transosseous venous rerouting to the scalp is evident on the lateral view. In this patient a satisfactory unilateral stent placement did not eliminate the gradient, which was difficult to explain. A second stent was placed on the other side (E and F), which did reduce the gradient to approximately 10 mm Hg. Some deformity of the stents is still evident on the lateral view (arrow). The patient’s headaches improved dramatically after the procedure, but her vision remained poor. Cases such as described in Figures 29-1 and 29-2 are almost always performed under general anesthesia due to patient discomfort. The use of general anesthesia can distort venous pressure readings, so in elective or semielective cases the declaration of a venous gradient may be more valid when performed in advance when the patient is awake. Delivery of the stent is unquestionably the most difficult component of this procedure. A triaxial catheter and sheath system is invariably necessary. The 8-mm Wallstent has favorable flexibility and low-profile advantages compared to most other similarly sized stents. Initial catheter access to the sinus can be difficult too. A hydrophilic 4F catheter over an 0.035″ wire can sometimes be more helpful than a microcatheter and microwire system. Care should always be taken to be gentle and measured in one’s manipulation of the wire. Subdural bleeding can be seen in a small number of patients after transvenous procedures and could be ascribed to a number of causes, including inadvertent retrograde perforation of subdural veins entering the sinuses. |

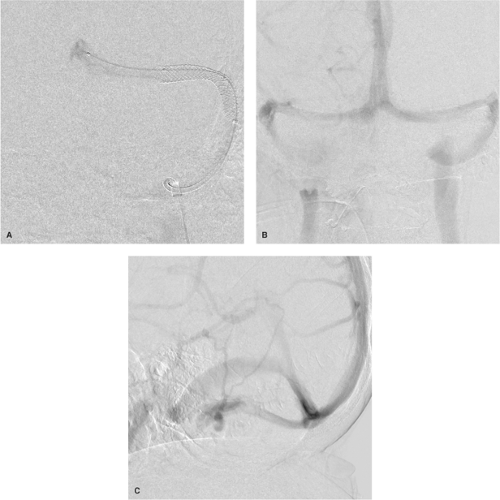

Figure 29-3. (A–C) Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: insensitivity of transarterial images for venous stenosis. This case of a young adult female is virtually identical to those given in Figures 29-1 and 29-2, with a similar therapeutic outcome. The poststenting image (A) shows some persistent narrowing of the stent in the midtransverse sinus, but the gradient was much improved by the procedure. The original study for this patient was an arteriogram, which was nondiagnostic. Even when the diagnosis is suspected, the AP (B) and lateral (C) venous phase images from the arteriogram are not helpful in identifying any degree of venous obstruction. Direct retrograde venography with manometry is necessary to confirm the diagnosis and to document the severity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|