30 | Dural Tears in the Cervical Spine |

| Case Presentation |

History and Physical Examination

A 50-year-old white male underwent an anterior cervical corpectomy of C5 and C6 using a fibular strut allograft followed by an instrumented posterior cervical fusion from C4 through C7 for cervical stenosis. The corpectomy was done using the Smith-Robinson approach from the left side. During the anterior corpectomy a pinhole-sized defect in the dura was noted after the removal of the posterior longitudinal ligament. The dural tear was not repaired. He was managed postoperatively with an anterior Jackson-Pratt drain (Baxter, Deerfield, IL). The drain was switched from bulb suction to gravity on postoperative day 1, then removed at the bedside on postoperative day 3. He was then discharged home with no signs or symptoms of a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak; specifically he had no headaches and no fluctuance, and his wound was dry without any drainage. He returned at 1 week because he noted that he was developing a small lump on the left side of his neck. The lump was not painful and he had no airway difficulties, no fevers or chills, and no neurological changes.

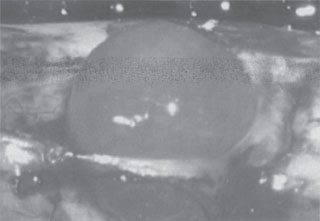

Figure 30–1 Patient with an asymptomatic pseudomeningocele that developed on postoperative day 7 from a dural tear that was not repaired. The fluctuant mass increased in size when the patient was supine.

On physical exam he was noted to have a fluctuant mass on the left side of his neck where his incision had been made. The mass was ~7 × 5 cm and was more pronounced when he was lying supine (Fig. 30–1).

Radiological Findings

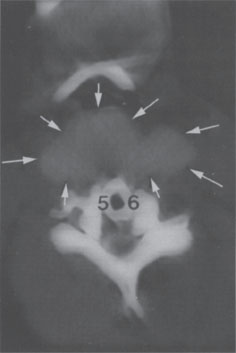

Imaging tests are not routinely needed to make a diagnosis of a CSF leak. If a pseudomeningocele has developed it can often be seen on a computed tomographic (CT) scan or with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 30–2). MRI is an excellent test to detect CSF fistulas and postoperative collections of CSF that are secondary to dural injury.1,2 The detection of very small dural leaks can be enhanced by the injection of a radionucleotide into the subarachnoid space and the use of radionucleotide cisternography.3

Figure 30–2 A dural “bleb” occurs when the dura has been disrupted but the subarachnoid layer remains intact.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a CSF leak is usually made intraoperatively by the direct visualization of clear CSF leaking from the dura. However, if the arachnoid layer of the dura remains intact no CSF will extravasate. Even if there is a small leak, extensive epidural bleeding may impede the intraoperative visualization of CSF. Increased thoracic or abdominal pressure caused by a Valsalva maneuver increases the pressure of the CSF, increasing the rate of fluid extravasation, and may aid in the diagnosis of a dural leak.4

If the extravasation of CSF is not recognized intraoperatively it is important to be alert for the signs and symptoms of a CSF leak so that it can be diagnosed postoperatively. Delayed wound healing, excessive clear or “Kool-Aid” like drainage, and subcutaneous fluid collections are all early signs of a dural leak. Symptoms of a persistent cerebrospinal leak are thought to be caused by a decrease in the CSF pressure. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, neck stiffness, photophobia, tinnitus, and positional headaches, which are worse when sitting up and improve in the recumbent position. In addition, the decreased pressure can increase traction on neural structures. Cranial nerve VI is the most sensitive to traction and so pressure changes in the CSF often manifest with strabismus or blurred vision.

If the clinical picture is not sufficient to make a diagnosis of a CSF leak, samples of the postoperative wound drainage can be sent to the laboratory to see if it contains β-2 transferrin.5 Beta-2 transferrin is a protein made by cerebral neuramidase. The presence of β-2 transferrin in a postoperative wound is very sensitive and specific to CSF leaks. Only one or two drops of fluid are required to conduct the test. The fluid may be analyzed from samples collected at the bedside or even from samples of wound drainage that have saturated the surgical dressing or the patient’s bed linens.6

| Background |

Dural tears after lumbar spine surgery are well documented and are among the most common complications, occurring in ~14% of all lumbar spine cases.7 However, little has been reported regarding the incidence or management of dural tears following cervical surgery. Bertalanffy and Eggert reviewed their complications after 450 consecutive anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion operations and found eight dural tears for an incidence of 1.8%.8

In the cervical spine, the spinal cord is covered by three meningeal layers consisting of the dura mater, the arachnoid layer, and the pia mater. The arachnoid layer is adhered to the undersurface of the dura mater, and CSF flows in the subarachnoid space between the arachnoid layer and the pia mater. The pia mater envelopes the spinal cord. A CSF leak will occur if both the dura and the arachnoid layers are disrupted. If the dura mater is disrupted but the arachnoid membrane remains intact a “bleb” or outpouching of the arachnoid membrane will occur (Fig. 30–3). No CSF will be seen extravasating if the arachnoid membrane is intact; however, this layer is very thin and can be disrupted easily by transient increases in CSF pressure such as those that occur with Valsalva maneuvers: coughing, sneezing, or even normal day-to-day activity.

Figure 30–3 Computed tomographic scan showing a large pseudo-meningocele (yellow arrows). (Courtesy of Dr. Henry Bohlman)