CHAPTER 35 DYSTONIA

The dystonias are an unusual group of movement disorders whose main feature is involuntary muscle contraction or spasm. The term dystonia was originally introduced by Hermann Oppenheim in 1911 to describe alterations in muscle tone and postural abnormalities that are seen in this condition. The concept of dystonia can be confusing because the term has been used to describe a symptom (e.g., a dystonic arm posture), a disease (primary torsion dystonia), or a syndrome. The dystonias constitute a relatively common group of movement disorders that encompass a wide range of conditions from those in which the only manifestation is dystonic muscle spasms to those in which dystonia is one part of a more severe neurological condition.

DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION

Dystonia is characterized by involuntary sustained muscle contractions affecting one or more sites of the body, frequently causing twisting and repetitive movements or abnormal postures.1 The movements range from slower twisting athetosis to rapid, shocklike jerky movements. They are repetitive and sometimes rhythmic and can be accompanied by tremor. Dystonic movements can be aggravated by movement (action dystonia) that can be nonspecific or task-specific (e.g., writing). Over time the dystonia can occur with less specific movements and eventually can be present at rest, leading to sustained abnormal postures.

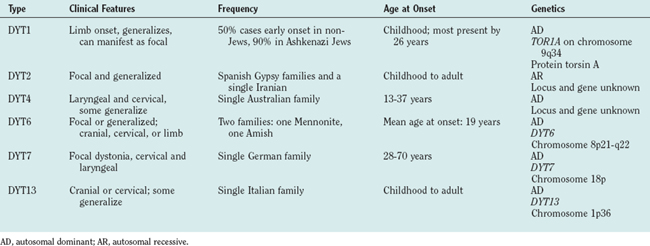

Three basic approaches are used to classify dystonia: age at onset, distribution of affected body parts, and etiology. The categories of age at onset and affected body distribution (Table 35-1) are important in describing clinical signs and have clinical implications for prognosis and treatment.

TABLE 35-1 Classification of Dystonia

±, with or without.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The true population incidence and prevalence of dystonia are unknown. The prevalence data available are usually based on studies of diagnosed cases only and therefore are underestimates of the real numbers. This is particularly the case with dystonia, which can manifest in a variety of ways, and a significant number of cases of focal dystonia are undiagnosed or even misdiagnosed. In an early study in the United States that was based on case note review, the prevalence for PTD was estimated to be 329 per million population. In more recent studies of diagnosed cases in Japan and Europe, the prevalence was estimated to be between 101 and 150 per million. The most reliable estimate is from an ongoing study in the northeast of England, where ascertainment was more complete, and some previously undiagnosed cases were identified. This finding has implied a prevalence rate of 485 per million. The prevalence of secondary dystonia is unknown, although it is estimated from case series that it may be less than 20% to 25% the rate for PTD.

In a study in South Tyrol in Austria, a random sample of the population older than 50 years was examined.2 Primary dystonia was diagnosed in 6 of the 707 individuals studied, implying a prevalence of 7320 per million in this age-selected population, although 95% confidence intervals were very wide, at 3190 to 15,640, because of the small sample. However, this indicates that in the aging population, dystonia is a relatively common neurological disorder.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The diagnosis of dystonia is based on clinical findings. Primary dystonia has no other neurological features apart from dystonia and tremor.3 Features suggestive of a secondary cause of dystonia are listed in Table 35-2. Investigations are usually performed to help rule out a secondary cause of dystonia.

TABLE 35-2 Clinical Features Suggestive of Secondary Dystonia

Primary Dystonia

Early-Onset Primary Torsion Dystonia (Dystonia Musculorum Deformans, Oppenheim’s Dystonia)

Most forms of early-onset PTD are genetic in origin, and Table 35-3 lists the genetic forms that have been identified to date. Most are autosomal dominant, some reported only in single families. The existence of autosomal recessive forms (DYT2) is controversial.

Focal Primary Torsion Dystonia

These are by far the commonest forms of dystonia. Usually sporadic, they have onset in adult life and remain focal in distribution. Families with autosomal dominant forms have been described, and it is believed that a proportion of the apparently sporadic cases may represent manifestation of a dominant gene with very low penetrance (estimated at 12% to 15%). The individual types are discussed as follows.

Writer’s cramp and task-specific limb dystonias

Writer’s cramp is the most common form of task-specific dystonia and, in contrast to craniocervical dystonia, is more common in men than in women. Onset usually occurs between the ages of 30 and 50 years and often starts with a feeling of tension in fingers and forearms that interferes with writing fluency. The pen is held abnormally forcefully as a result of dystonic contraction of hand and/or forearm muscles. This commonly involves excessive flexion of the thumb and index finger with pronation of the hand and ulnar deviation of the wrist. Affected individuals may also experience lifting of the thumb or index finger off the pen or isolated extension of fingers. Up to 50% of patients also experience upper limb tremor, either on writing or a postural tremor. Strain and aching, particularly in affected forearm muscles, is common on writing, but pain is an uncommon feature.