Chapter 43 Eating, body shape and health

Although a large proportion of the world’s population suffers from malnutrition, a growing proportion suffers from overeating and eating conditions are associated with a growing number of health problems. Problems with eating are the product of overabundance of palatable food and reduced exercise on the one hand, and unrealistic ideals about body shape on the other. The system responsible for appetite regulation is unable to cope adequately with these pressures. Most urgent is the increase in obesity in western society. Obesity has well-documented health risks, including heart disease (see pp 106–107), diabetes (see pp. 124–125), high blood pressure and stroke. Of particular concern is the increase in childhood obesity, resulting in a range of health-related complications (Malecka-Tendera & Mazur, 2006). Obesity also has psychological effects, with increased depression, feelings of ugliness and low self-esteem. Consequently, many overweight individuals diet to lose weight. However, disorders of eating associated with attempts to diet are also increasing, and the modern clinician is faced with the conundrum of how to promote healthy eating amongst people who are underweight through excessive dieting and how to help overweight individuals lose weight (see Case study).

Assessing weight status

The body mass index (BMI: Table 1) assesses weight status, and helps identify people who are outside the normal weight range. BMI figures are not definitive measures of health. The BMI of many elite athletes is above the ‘normal’ range, but their excess is muscle rather than fat. In general, however, BMI remains a good approximation of weight status.

Table 1 Body mass index (BMI) calculation and classification∗

| BMI | Classification |

|---|---|

| <18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5–24.9 | Normal |

| 25.0–29.9 | Overweight |

| 30.0–34.9 | Mildly obese |

| 35.0–39.9 | Moderately obese |

| 40.0 + | Severely obese |

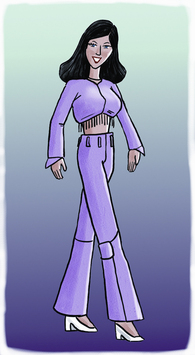

The perfect body

The ideal body shape portrayed in magazines has changed markedly over time, and anyone looking at pictures of women used as models in art across the ages will see remarkable changes in physique. Today the figure portrayed as ideal, that is, excessively thin and athletic but often with enhanced breast size, is unattainable for the vast majority of women. This is most extreme in the use of ‘size zero’ fashion models in advertisements aimed at women. Even the dolls idolized by young girls have BMIs in the anorexic range (Fig. 1), coupled with a bust size that could only be obtained through surgery. While the ideal has got thinner, the average body size has increased, so the disparity between ideal and actual body shapes has grown. The result is widespread dissatisfaction with body shape, and it is perhaps no coincidence that levels of depression in women have risen in parallel with these concerns (Sawdon et al., 2007). Men, too, are increasingly concerned with body shape, although eating disorders for men are concentrated in professions where weight is an issue (e.g. ballet dancing, jockeys and some athletes) and in homosexual men, who appear more sensitive to societal pressures (Hospers & Jansen, 2005; see pp. 52–53).