Education and Training

Dorothy E. Stubbe

Eugene V. Beresin

If you treat an individual as he is, he will remain as he is.

But if you treat him as if he were what he ought to be and could be, he will become what he ought to be and could be.

–Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship VIII-4

Background and Context

There is a dearth of child and adolescent psychiatrists to treat the nation’s children and their families with serious mental health needs (1,2). Epidemiological studies suggest that 5% to 9% of children suffer from “extreme functional impairments” from psychiatric disorders, and up to 10% to 20% have a diagnosable disorder (3). There are approximately 7,000 child and adolescent psychiatrists in the United States, considerably below the estimated 20,000 needed to provide the psychiatric care of seriously psychiatrically ill children and youth within a multidisciplinary system of care. Child and adolescent psychiatry researchers are similarly insufficient to meet the need to advance our knowledge on the etiology and treatment of these disorders (4,5,6,7,8).

Recruiting, training, and mentoring the next generation of child and adolescent psychiatrists is one of the major challenges, as well as one of the major opportunities, of the field. Graduates face a plethora of career opportunities in clinical practice, academics, and research. Lifestyle and improving remuneration also draw medical graduates to the field (9). Yet there are many challenges facing training programs and obstacles to recruitment. Enhanced training requirements, a paucity of funding for graduate medical education of subspecialties, and depleted faculty time to provide the required mentorship and teaching are ongoing challenges. The vigor, rejuvenation, and satisfaction of training the next generation of superior physician clinicians and scientists are the enduring rewards (10).

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Residency Training in the United States

Historical Note

Child psychiatry in this country began with the establishment of the child guidance clinics, the first of which was the Juvenile Psychopathic Institute in Chicago, established by Dr. William Healy in 1909. As child guidance clinics grew in number and in size, it became clear that psychiatrists who worked with children must have training that was more extensive and specific than that obtained in their general psychiatry residency. A major conference held in 1944 under the auspices of the Commonwealth Fund provided a standard set of skill areas that should be mastered by psychiatrists who treat children and their families (11). These skill areas included growth and development, psychodynamics, working with parents, administration, and community organizations.

In 1946, World War II was over and there was a renewed vigor to provide for the children of the new baby boom. The Mental Health Act of 1946 provided monies for the training of child psychiatrists. Additionally, the American Association of Psychiatric Clinics for Children (AAPCC) was formed. The training committee provided an approval process for potential training sites, including an application and survey. About half of the child guidance clinics were approved as training sites in this way.

The American Academy of Child Psychiatry (AACP) was founded in 1953. Initially a by-invitation-only organization, the AACP was committed to ensure training accreditation within the medical specialty, not only through child guidance clinics. After a debate of whether child psychiatry was more appropriately a pediatric or psychiatric subspecialty, the choice was made for psychiatry. The American Board of Medical Specialties approved the subspecialty and examined its first candidates in child psychiatry in 1959.

Inextricably linked to subspecialty certification are standardized training criteria formulated through the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The ACGME Residency Review Committee (RRC) in Psychiatry oversees periodic surveys and decides upon accreditation status of each program for training (12). This approach was much more medically oriented than the earlier AAPCC reviews. The ACGME demanded that child psychiatry training programs be linked to accredited general psychiatry residency programs and to medical centers approved by the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Hospitals. These requirements forced the child guidance clinics interested in training to abscond from their exclusive community roots and to become attached to medical schools. It also stimulated the development of new child psychiatry training programs that were situated in medical centers, rather than freestanding in the community.

In 1969, the Academy opened its doors to all child psychiatrists who graduated from, or who were in training in, ACGME-approved programs. The AACP expanded to capture the treatment of adolescents into its purview in 1989, becoming the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) of today. The American Association of directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) and the Association for Academic Psychiatry (AAP) are more recently formed organizations specifically devoted to education and training.

As with all of medicine, training and education is both an art and a science. A good training director serves as the conductor for the symphony—transmitting a serious and passionate commitment to the highest standards of comprehensive care for children, adolescents, and families, a dedication to residents and their personal and professional growth and excellence as physicians, and a vision of the field—where it is now and where it needs to go. In each institution, the instrumentation and symphonic music will vary, but the basic principles apply. Excellence in training requires coordinated and well constructed training experiences that adhere to all training requirements, within multiple systems (medical school, hospital, clinics), synchronized with the goals and structure of the broader administration (Dean, hospital administration, Chair of Department of Psychiatry, Division Chair, Directors of Residency Training) and harmonized with the resources and needs of the Division and Department.

Recruitment, Portals of Entry, and Training Program Types (Traditional and Novel) Recruitment and Workforce Issues

There is a nationwide shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists. A survey by Beresin and Borus of accredited child psychiatry fellowships identified a shortage of recruits for residency and faculty positions in child and adolescent psychiatry in the late 1980s (13). This shortage has continued (1). Lack of exposure to child and adolescent psychiatry during medical school education, increasing levels of educational debt burden, long years of residency training, and relatively smaller income potential in general psychiatry, as well as in child and adolescent psychiatry, are factors that influence a medical student’s career decision (14,15). Other obstacles to recruitment include inadequate support in academic institutions, decreasing graduate medical education (GME) funding, and decreasing clinical revenues in the managed care environment (16).

In spite of the shortages, child and adolescent psychiatry has made impressive progress in its scientific knowledge base through research, especially in neuroscience, developmental science and genetics (17). Additionally, there is a growing recognition of the need for child and adolescent psychiatry by policymakers and the public at large. The Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health in 2000, and the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health in 2003, have both acknowledged the shortage as a national crisis. Pending legislation proposes loan forgiveness programs for child and adolescent psychiatry trainees and full GME funding for shortage specialties such as child and adolescent psychiatry. There is increasing media coverage on mental health problems of children and adolescents, as the public becomes more aware and concerned about these vital issues facing our youth. The public has become increasingly interested in issues of mental health and effective interventions, as the aftermaths of such disasters as the September 11th, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center and Hurricane Katrina in the Gulf Coast in August 2005 have left not only physical, but more permanently, mental health scars on the population.

Recruitment efforts in child and adolescent psychiatry focus on three salient areas: 1) ensuring that talented, interested physicians have positive exposure and engagement early in training to the field of child and adolescent psychiatry; 2) providing training opportunities that are appealing and ensure ongoing engagement of the resident in work with children and families; and 3) the positive aspects of lifestyle, remuneration, and the plethora of job opportunities for individuals seeking a career in the field.

The Transition from General Psychiatry Residency to Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Developing a professional identity as a child and adolescent psychiatrist is a core aspect of residency education and training. While many residents have had a longstanding interest in children and families, and look forward with great enthusiasm finally to working in the field, assuming the role of a child and adolescent psychiatrist is fraught with challenges. Many stressors inherent in the transition from general psychiatry residency to child and adolescent residency may interfere with the educational process (18).

By the time a resident enters child and adolescent residency training he/she has had at least three initiations into new territory: medical school, internship, and general psychiatry residency. The entry into child and adolescent residency training is yet another “beginning,” with the attendant narcissistic challenge of starting over and having to master new skills, having just achieved competence and confidence with adults. The loss of working with adults threatens losing skills acquired over three to four years.

Child and adolescent residents working clinically with children use nonverbal skills, deal with primitive defenses, and manage behavior in individuals who are far less able to use advanced cognitive skills and concepts than the adults with whom they previously were quite comfortable. They also have to manage new and complex countertransference problems, such as “adopting” their patients, undoing the actions of “incompetent” parents, and overidentifying with their child patients. They are mandated reporters, and must “turn in” parents to authorities. And they now must serve as authorities for schools, courts, and social service agencies in making decisions that have a profound effect on the child and family, including decisions about custody, placement, incarceration—all at a time when they have relatively limited knowledge and skill in the field. They must shoulder the responsibility of working with dying children and grieving parents. At a less intense level, they have to answer complex developmental and behavioral questions from parents, pediatricians, and allied professionals when they are themselves novices. The new residents have to face all this in the context of increased time demands for calls, emails, paperwork and meetings. They need to help deeply troubled children and families at a time when there are limited resources for outpatient and inpatient care, and far too few clinicians in all child-related healthcare disciplines to take on referrals for the comprehensive care of the children and families they serve. Finally, child and adolescent psychiatry is more demanding than general psychiatry, in that residents need to embrace a developmental model that requires greater integration of the many factors that impact child development, such as genetics, family, culture, educational systems, and social forces.

This stress is heightened by the loss of the previous peer group from general psychiatry residency. Colleagues from general residency are graduating and beginning their careers. Many child and adolescent psychiatry residents are shouldering high educational debt and have to put off their loan repayments for another two years. This training also occurs at a time when many residents are feeling pressure to establish new love relationships, or have started having families and struggle to make a living and spend precious time with their families, all while managing a rigorous and stressful residency program.

Training programs need to appreciate the difficulty of the transition, and promote means for residents to cope with these stresses. The effective collaboration between the residency training coordinator and the training director is crucial to this task. At the admissions level, screening for the most mature, adaptive, and resilient candidates is helpful. Trying to assemble

a residency class that is cohesive and supportive is also useful. The program should provide time for residents to meet with faculty and discuss the issues and problems involved in the transition. Alerting the faculty to these transition issues is vital, so they may be addressed in individual supervision. Finding many opportunities to have residents observe faculty treating children and families and serving as consultants provides the means for them to learn skills and have working role models for identification. It may be valuable for some residents to continue treating adult patients, either in the program or through moonlighting, to help preserve previously acquired skills.

a residency class that is cohesive and supportive is also useful. The program should provide time for residents to meet with faculty and discuss the issues and problems involved in the transition. Alerting the faculty to these transition issues is vital, so they may be addressed in individual supervision. Finding many opportunities to have residents observe faculty treating children and families and serving as consultants provides the means for them to learn skills and have working role models for identification. It may be valuable for some residents to continue treating adult patients, either in the program or through moonlighting, to help preserve previously acquired skills.

Traditional and Innovative Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Training Models

There has been an ongoing debate about the most effective, efficient, and appealing methods to train competent child and adolescent psychiatrists. There were early proposals that child and adolescent psychiatry should split from general psychiatry, as did pediatrics from internal medicine. There have been numerous other proposals, as well. The primary impetus for new and more innovative training portals are twofold: 1) a philosophy of training that endorses innovative training tracks to more fully ensure quality education of competent graduates by optimizing training methods; and 2) enhancing recruitment into the field by providing a variety of attractive and novel training portals.

Existing Portals

Traditional Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Training

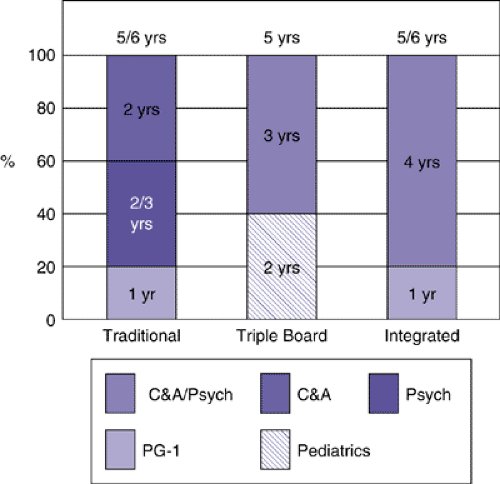

Training in child and adolescent psychiatry generally occurs after medical school, and after a first post graduate (PG-1) year that includes at least four months of general medicine or pediatrics, two months of neurology, and two years of general psychiatry training. However, with recent revisions of the RRC training requirements, child and adolescent psychiatry training may commence any time following graduation from medical school. Training in child and adolescent psychiatry is for two years, and the first year of training may count for the PG-4 year of general psychiatry training. Thus, traditional training in child and adolescent psychiatry may be completed in either five or six years after completing medical school. Most residents enter at the PG-4 year. They experience pressures to finish training; to address family, finances, and career development issues, and for some, to plan ahead toward further training such as forensics, addictions, or research fellowships. Many residents are eager to work with children and families more quickly. Other residents prefer to complete the full four years of general psychiatry training prior to starting child and adolescent psychiatry residency. They wish to take advantage of the opportunity for elective experiences, chief residency, and/or to consolidate skills in their work with adults.

Integrated Training

Triple Board

An innovative five-year training sequence in pediatrics, general psychiatry, and child and adolescent psychiatry, better known as the “Triple Board,” began as a pilot training experiment in 1985 and was approved nationwide as a combined residency in 1992 (19). The “Triple Board” concept was to create an alternative pathway of training to become a child and adolescent psychiatrist that would combine pediatric, general psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry training and would allow a path shorter than would be required in the conventional (additive) training sequence of seven or eight years. One of the goals of the combined training program was to create a nucleus of academically based child and adolescent psychiatrists who were trained and socialized as pediatricians, and who could bridge a gap between the pediatric and the child and adolescent psychiatry communities. Additionally, it was hoped that this core of “Triple Boarders” could serve as a magnet in the academic environment to attract medical students to the specialty field of child and adolescent psychiatry. This track is sponsored by the ABPN, the ABPN Committee on Certification in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the American Board of Pediatrics. Followup suggests that this training track has trained competent and successful clinicians and scientists, most of whom practice predominantly child and adolescent psychiatry, although often in a setting with medically compromised children (20). Although the rotations and integration of the three specialties varies from program to program, all programs provide 24 months of pediatrics, and 18 months each of general and child and adolescent psychiatry. Upon completion of training, residents may sit for board examinations in all three disciplines. There are presently ten approved Triple Board training programs.

Integrated Training Tracks

Integrated training specifies a residency that combines training in two or more disciplines in a contiguous, rather than consecutive, training model. This approach, initially developed and implemented in the 1970s at the University of Pittsburgh by Peter Henderson, M.D., combined child and general psychiatry training from the onset of training. Since that time, a few more institutions have adopted similar models of integrated training. Other programs have the flexibility to initiate a variety of child and adolescent psychiatry clinical experiences within the general psychiatry residency for individuals with a declared interest. Although programs vary in the specific manner in which they configure training requirements, all share in common the principle of exposing residents early and continuously to children and childhood pathology (21).

Training programs with an integrated track meet all existing program requirements for residency education in both general psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry. Programs with integration seek to allow knowledge, skills and attitude-building in a developmental context of patient care, and to solidify the trainee’s identity as a child psychiatrist early on. Most integrated training occurs within the context of a five-year clinical training program.

Academic Integrated Training Track

In the United States, there is a dearth of academic child and adolescent psychiatrists, and physicians adding to the research base on the etiologies and effective treatments of childhood psychiatric disorders (5,22). Integrated training in general psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and research allows medical students to move directly into an integrated child-adult psychiatric residency and research training program that is constructed to do justice to the basic developmental sciences and efficacious interventions while not neglecting the fundamentals of psychiatry. The major goal of this alternative training route is to provide a national model to increase the number and quality of child and adolescent psychiatrists in research careers.

In response to the Institute of Medicine’s report on the shortage of psychiatrist researchers, the National Institute of Mental Health established the National Psychiatry Training Council (NPTC) (23). With the support of the NPTC, of which he was co-chair, James Leckman, M.D. and others proposed a six-year integrated child and adolescent psychiatry academic track (24) that has become a reality at the Yale Child Study Center and the University of Colorado and is being considered in other institutions. This program highlights three basic principles: 1) early identity formation as a child and adolescent psychiatric researcher; 2) the developmental continuity of training; and 3) individualization of training and “tooling” opportunities to prepare the trainee for a research career. The program has a predominantly pediatric internship year, followed by a Basic Skills year that allows for the identification of a research team and mentor, appropriate coursework, as well as clinical experiences in evidence-based and long-term insight-oriented treatments. Martin and colleagues have provided a detailed program description of an academic track program (25). Research and clinical experiences with adults, children, adolescents and families are integrated throughout the residency. Figure 1.4.1 summarizes the current training options in child and adolescent psychiatry residency training.

Proposed Portals: Not Presently Approved

Post-Pediatric Training

A newly proposed portal utilizes the Triple Board model for training individuals who have fully completed three years of pediatric training. This model includes 18 months each of general psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry, and proposes to incur board eligibility in both general and child and adolescent psychiatry.

This model would allow newly graduated pediatricians or pediatricians who have been in practice for a number of years and wish to retool in child and adolescent psychiatry to do so in three years, rather than the usual four. Table 1.4.1 contrasts the potential advantages and disadvantages of post-pediatric training and triple board (TB) training.

TABLE 1.4.1 POST-PEDIATRIC TRAINING: COMPARISON WITH TRIPLE BOARD (TB) TRAINING | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fast Tracking

A more controversial discussion regards the creation of a four-year training pilot in child and adolescent psychiatry and general psychiatry. This would essentially include an internship year with four months of primary care and two months of neurology, followed by 30 months of general and child and adolescent psychiatry. This portal may have appeal to entering students for whom length of training and student debt are salient, and has the advantage of increasing the number of practitioners in the field more quickly. However, it does not have broad support as an option that provides sufficient training.

Another controversial portal is one in which child and adolescent psychiatry may be pursued directly, without training in general psychiatry. In many European and other developed countries, the major pathway to a career in child psychiatry is via a program that trains specifically in child psychiatry, including basic training in general psychiatry, pediatrics, and neurology. In most of these nations, child psychiatrists are not fully trained in adult psychiatry. The model would provide a direct pathway to child and adolescent psychiatry after pediatric internship and other pediatric experiences. The training may be four or five years. Again, this model has not received broad support of the training community or accrediting bodies.

Competency-Based Assessment in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Training

Didactic and Clinical Components: The Core Competencies

The training of competent physicians is the goal of all residency training. However, until recently the exact definition of “competent” and the specific areas in which the practitioner was to have attained competency had been only vaguely defined. Thus, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (26) identified six core areas in which a resident is required to obtain competence. Programs must define the specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes required for competence in each of the six Core Competencies, and provide educational

experiences as needed in order for residents to demonstrate competence (27,28). Table 1.4.2 gives a summary of the Core Competencies in graduate medical education.

experiences as needed in order for residents to demonstrate competence (27,28). Table 1.4.2 gives a summary of the Core Competencies in graduate medical education.

TABLE 1.4.2 CORE COMPETENCIES IN RESIDENCY TRAINING | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In medical practice, levels of expertise range from novice to master. The residency training requirements of “competence” is that level of expertise which may be expected of a new practitioner in the field. This vague definition is transformed into appropriate and identifiable benchmarks for competency. “Is this person safe to practice independently?” is the critical question to answer in the affirmative in the assessment of attainment of competency prior to graduation.

Competency-based training requires that programs:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree