Emergency Psychiatric Medicine

23.1 Suicide

23.1 Suicide

Suicide is derived from the Latin word for “self-murder.” It is a fatal act that represents the person’s wish to die. There is a range, however, between thinking about suicide and acting it out. Some plan for days, weeks, or even years before acting, while others take their lives seemingly on impulse without premeditation. Lost in the definition are intentional misclassifications of the cause of death, accidents of undetermined cause, and so-called chronic suicide (e.g., deaths through alcohol and substance abuse and consciously poor adherence to medical regimens for addiction, obesity, and hypertension). For other terms in the literature on suicide, see Table 23.1-1.

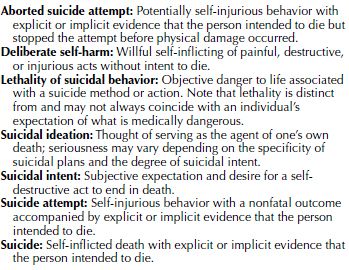

Table 23.1-1

Table 23.1-1

Terms Comprising Suicidal Ideation and Behavior

In psychiatry, suicide is the primary emergency, with homicide and failure to diagnose an underlying potentially fatal illness representing other, less common psychiatric emergencies. Suicide is to the psychiatrist as cancer is to the internist—the psychiatrist may provide optimal care, yet the patient may die by suicide nonetheless. Thus, suicide is impossible to predict, but numerous clues can be seen. There are also some generally accepted standards of care that facilitate risk reduction, as well as lessen the likelihood of successful litigation, should a patient death occur and a lawsuit be filed. Suicide also needs to be considered in terms of the devastating legacy that it leaves for those who have survived a loved one’s suicide, the impact it has on the treating physician, and the ramification for the clinicians who cared for the decedents. Perhaps the most important concept regarding suicide is that it is almost always the result of mental illness, usually depression, and is amenable to psychological and pharmacological treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There are over 35,000 deaths per year (approximately 100 per day) in the United States attributed to suicide. This is in contrast to approximately 20,000 deaths annually from homicide. It is estimated that there is a 25 to 1 ratio between suicide attempts and completed suicides. Although significant shifts were seen in the suicide death rates for certain subpopulations during the past century (e.g., increase adolescent and decreased elderly rates), the rate remains fairly constant, averaging about 12 per 100,000 through the 20th century and into the first decade of the 21st century. Suicide is currently ranked the tenth overall cause of death in the United States, after heart disease, cancer, chronic lower respiratory diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, accidents, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, and kidney disease.

Suicide rates in the United States are the midpoint of the rates for industrialized countries. Internationally, suicide rates range from highs of more than 25 per 100,000 persons in Lithuania, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Russia, Belarus, and Guyana to fewer than 10 per 100,000 in Portugal, the Netherlands, Australia, Spain, South Africa, Italy, Egypt, and others.

A state-by-state analysis of suicides in the past decade revealed that New Jersey had the nation’s lowest suicide rate for both sexes and Montana had the nation’s highest rate. Montana and Wyoming had the highest rates for men, and Alaska and Idaho had the highest rates for women. The prime suicide site in the world is the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, with 1,600 suicides committed there since the bridge opened in 1937.

Risk Factors

Gender Differences. Men commit suicide more than four times as often as women, regardless of age or race, in the United States—despite the fact that women attempt suicide or have suicidal thoughts three times as often as men. Although this disparity remains unclear, it may be related to the methods used. Men are more likely than women to commit suicide using firearms, hanging, or jumping from high places. Women, on the other hand, more commonly take an overdose of psychoactive substances or poison. The use of firearms among women, however, is increasing. In states with gun control laws, the use of firearms has decreased as a method of suicide. Globally, the most common method of suicide is hanging.

Age. For all groups, suicide is rare before puberty. Suicide rates increase with age and underscore the significance of the midlife crisis. Among men, suicides peak after age 45; among women, the greatest number of completed suicides occurs after age 55. Rates of 29 per 100,000 population occur in men age 65 or older. Older persons attempt suicide less often than younger persons, but are more often successful. Although they represent only 13 percent of the total population, older persons account for 16 percent of suicides.

The suicide rate, however, is rising among young persons. Suicide is the third leading cause of death in those aged 15 to 24 years, after accidents and homicides. Attempted suicides in this age group number between 1 million and 2 million annually. Most suicides now are among those aged 35 to 64.

Race. Suicide rates among white men and women are approximately two to three times as high as for African American men and women across the life cycle. Among young persons who live in inner cities and certain Native American and Alaskan Native groups, suicide rates have greatly exceeded the national rate. Suicide rates among immigrants are higher than those in the native-born population.

Religion. Historically, Protestants and Jews in the United States have had higher suicide rates than Catholics. Muslims have much lower rates. The degree of orthodoxy and integration may be a more accurate measure of risk in this category than simple institutional religious affiliation.

Marital Status. Marriage lessens the risk of suicide significantly, especially if there are children in the home. Single, never-married persons register an overall rate nearly double that of married persons. Divorce increases suicide risk, with divorced men three times more likely to kill themselves as divorced women. Widows and widowers also have high rates. Suicide occurs more frequently than usual in persons who are socially isolated and have a family history of suicide (attempted or real). Persons who commit so-called anniversary suicides take their lives on the day a member of their family did. Homosexual men and women appear to have higher rates of suicide than heterosexuals.

Occupation. The higher the person’s social status, the greater the risk of suicide, but a drop in social status also increases the risk. Work, in general, protects against suicide. Among occupational rankings, professionals, particularly physicians, have traditionally been considered to be at greatest risk. Other high-risk occupations include law enforcement, dentists, artists, mechanics, lawyers, and insurance agents. Suicide is higher among the unemployed than among employed persons. The suicide rates increase during economic recessions and depressions and decrease during times of high employment and during wars.

PHYSICIAN SUICIDES. The weight of current evidence supports the conclusion that both male and female physicians in the United States have elevated rates of suicide. It is estimated that approximately 400 physicians commit suicide each year in the United States. United Kingdom and Scandinavian data show that the suicide rate for male physicians is two to three times that found in the general male population of the same age. Female physicians have a higher risk of suicide than other women. In the United States, the annual suicide rate for female physicians is about 41 per 100,000, compared with 12 per 100,000 among all white women over 25 years of age. Studies show that physicians who commit suicide have a mental disorder, most often depressive disorder, substance dependence, or both. Both male and female physicians commit suicide significantly more often by substance overdoses and less often by firearms than persons in the general population; drug availability and knowledge about toxicity are important factors in physician suicides. Among physicians, psychiatrists are considered to be at greatest risk, followed by ophthalmologists and anesthesiologists, but all specialties are vulnerable.

Climate. No significant seasonal correlation with suicide has been found. Suicides increase slightly in spring and fall but, contrary to popular belief, not during December and holiday periods.

Physical Health. The relation of physical health and illness to suicide is significant. Previous medical care appears to be a positively correlated risk indicator of suicide: About one third of all persons who commit suicide have had medical attention within 6 months of death, and a physical illness is estimated to be an important contributing factor in about half of all suicides.

Factors associated with illness that contribute to both suicides and suicide attempts are loss of mobility, especially when physical activity is important to occupation or recreation; disfigurement, particularly among women; and chronic, intractable pain. Patients on hemodialysis are at high risk. In addition to the direct effects of illness, the secondary effects—for example, disruption of relationships and loss of occupational status—are prognostic factors.

Certain drugs can produce depression, which may lead to suicide in some cases. Among these drugs are reserpine (Serpasil), corticosteroids, antihypertensives, and some anticancer agents. Alcohol-related illnesses, such as cirrhosis, are associated with higher suicide rates.

Mental Illness. Almost 95 percent of all persons who commit or attempt suicide have a diagnosed mental disorder. Depressive disorders account for 80 percent of this figure, schizophrenia accounts for 10 percent, and dementia or delirium for 5 percent. Among all persons with mental disorders, 25 percent are also alcohol dependent and have dual diagnoses. Persons with delusional depression are at highest risk of suicide. A history of impulsive behavior or violent acts increases the risk of suicide as does previous psychiatric hospitalization for any reason. Among adults who commit suicide, significant differences between young and old exist for both psychiatric diagnoses and antecedent stressors. Diagnoses of substance abuse and antisocial personality disorder occurred most often among suicides in persons less than 30 years of age and diagnoses of mood disorders and cognitive disorders most often among suicides in those age 30 and above. Stressors associated with suicide in those under 30 were separation, rejection, unemployment, and legal troubles; illness stressors most often occurred among suicide victims over age 30.

Psychiatric Patients. Psychiatric patients’ risk for suicide is 3 to 12 times that of nonpatients. The degree of risk varies, depending on age, sex, diagnosis, and inpatient or outpatient status. Male and female psychiatric patients who have at some time been inpatients have five and ten times higher suicide risks, respectively, than their counterparts in the general population. For male and female outpatients who have never been admitted to a hospital for psychiatric treatment, the suicide risks are three and four times greater, respectively, than those of their counterparts in the general population. The higher suicide risk for psychiatric patients who have been inpatients reflects that patients with severe mental disorders tend to be hospitalized—for example, patients with depressive disorder who require electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The psychiatric diagnosis with greatest risk of suicide in both sexes is a mood disorder.

Those in the general population who commit suicide tend to be middle aged or older, but studies increasingly report that psychiatric patients who commit suicide tend to be relatively young. In one study, the mean age of male suicides was 29.5 years and that of women 38.4 years. The relative youthfulness in these suicide cases was partly attributed to two early-onset, chronic mental disorders—schizophrenia and recurrent major depressive disorder—which account for just over half of these suicides, and so reflects an age and diagnostic pattern found in most studies of psychiatric patient suicides.

A small, but significant, percentage of psychiatric patients who commit suicide do so while they are inpatients. Most of these do not kill themselves in the psychiatric ward itself, but on the hospital grounds, while on a pass or weekend leave, or when absent without leave. For both sexes, the suicide risk is highest in the first week of the psychiatric admission; after 3 to 5 weeks, inpatients have the same risk as the general population. Times of staff rotation, particularly of the psychiatric residents, are periods associated with inpatient suicides. Epidemics of inpatient suicides tend to be associated with periods of ideological change on the ward, staff disorganization, and staff demoralization.

The period after discharge from the hospital is also a time of increased suicide risk. A follow-up study of 5,000 patients discharged from an Iowa psychiatric hospital showed that in the first 3 months after discharge, the rate of suicide for female patients was 275 times that of all Iowa women; the rate of suicide for male patients was 70 times that of all Iowa men. Studies show that one third or more of depressed patients who commit suicide do so within 6 months of leaving a hospital; presumably they have relapsed.

The main risk groups are patients with depressive disorders, schizophrenia, and substance abuse and patients who make repeated visits to the emergency room. Patients, especially those with panic disorder, who frequent emergency services, also have an increased suicide risk. Thus, mental health professionals working in emergency services must be well trained in assessing suicidal risk and making appropriate dispositions. They must also be aware of the need to contact patients at risk who fail to keep follow-up appointments.

DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS. Mood disorders are the ones most closely linked to suicide. Approximately 60 to 70 percent of suicide victims suffered a significant depression at the time of their deaths. The lifetime risk of death by suicide among individuals with bipolar disorder is approximately 15 to 20 percent, and suicide is more likely during depressed states rather than manic states.

More patients with depressive disorders commit suicide early in the illness rather than later; more depressed men than women commit suicide; and the chance of depressed persons’ killing themselves increases if they are single, separated, divorced, widowed, or recently bereaved. Patients with depressive disorder in the community who commit suicide tend to be middle aged or older.

Social isolation enhances suicidal tendencies among depressed patients. This finding is in accord with the data from epidemiological studies showing that persons who commit suicide may be poorly integrated into society. Suicide among depressed patients is likely at the onset or the end of a depressive episode. As with other psychiatric patients, the months after discharge from a hospital are a time of high risk.

Regarding outpatient treatment, most depressed suicidal patients had a history of therapy; however, less than half were receiving psychiatric treatment at the time of suicide. Of those who were in treatment, studies have shown that treatment was less than adequate. For example, most patients who received antidepressants were prescribed subtherapeutic doses of the medication.

SCHIZOPHRENIA. The suicide risk is high among patients with schizophrenia: Up to 10 percent die by committing suicide. In the United States, an estimated 4,000 patients with schizophrenia commit suicide each year. The onset of schizophrenia is typically in adolescence or early adulthood, and most of these patients who commit suicide do so during the first few years of their illness; therefore, those patients with schizophrenia who commit suicide are young.

Thus, the risk factors for suicide among patients with schizophrenia are young age, male gender, single marital status, a previous suicide attempt, a vulnerability to depressive symptoms, and a recent discharge from a hospital. Having three or four hospitalizations during their 20s probably undermines the social, occupational, and sexual adjustment of possibly suicidal patients with schizophrenia. Consequently, potential suicide victims are likely to be male, unmarried, unemployed, socially isolated, and living alone—perhaps in a single room. After discharge from their last hospitalization, they may experience a new adversity or return to ongoing difficulties. As a result, they become dejected, experience feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, reach a depressed state, and have, and eventually act on, suicidal ideas. Only a small percentage committed suicide because of hallucinated instructions or a need to escape persecutory delusions. Up to 50 percent of suicides among patients with schizophrenia occur during the first few weeks and months after discharge from a hospital; only a minority commit suicide while inpatients.

ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE. Up to 15 percent of all alcohol-dependent persons commit suicide. The suicide rate for those who are alcoholic is estimated to be about 270 per 100,000 annually; in the United States, between 7,000 and 13,000 alcohol-dependent persons commit suicide each year.

About 80 percent of all alcohol-dependent suicide victims are male, a percentage that largely reflects the sex ratio for alcohol dependence. Alcohol-dependent suicide victims tend to be white, middle aged, unmarried, friendless, socially isolated, and currently drinking. Up to 40 percent have made a previous suicide attempt. Up to 40 percent of all suicides by persons who are alcohol dependent occur within a year of the patient’s last hospitalization; older alcohol-dependent patients are at particular risk during the postdischarge period.

Studies show that many alcohol-dependent patients who eventually commit suicide are rated depressed during hospitalization and up to two thirds are assessed as having mood disorder symptoms during the period in which they commit suicide. As many as 50 percent of all alcohol-dependent suicide victims have experienced the loss of a close, affectionate relationship during the previous year. Such interpersonal losses and other types of undesirable life events are probably brought about by the alcohol dependence and contribute to the development of the mood disorder symptoms, which are often present in the weeks and months before the suicide.

The largest group of male alcohol-dependent patients is composed of those with an associated antisocial personality disorder. Studies show that such patients are particularly likely to attempt suicide; to abuse other substances; to exhibit impulsive, aggressive, and criminal behaviors; and to be found among alcohol-dependent suicide victims.

OTHER SUBSTANCE DEPENDENCE. Studies in various countries have found an increased suicide risk among those who abuse substances. The suicide rate for persons who are heroin dependent is about 20 times the rate for the general population. Adolescent girls who use intravenous substances also have a high suicide rate. The availability of a lethal amount of substances, intravenous use, associated antisocial personality disorder, a chaotic lifestyle, and impulsivity are some of the factors that predispose substance-dependent persons to suicidal behavior, particularly when they are dysphoric, depressed, or intoxicated.

PERSONALITY DISORDERS. A high proportion of those who commit suicide have various associated personality difficulties or disorders. Having a personality disorder may be a determinant of suicidal behavior in several ways: by predisposing to major mental disorders such as depressive disorders or alcohol dependence; by leading to difficulties in relationships and social adjustment; by precipitating undesirable life events; by impairing the ability to cope with a mental or physical disorder; and by drawing persons into conflicts with those around them, including family members, physicians, and hospital staff members.

An estimated 5 percent of patients with antisocial personality disorder commit suicide. Suicide is three times more common among prisoners than among the general population. More than one third of prisoner suicides have had past psychiatric treatment, and half have made a previous suicide threat or attempt, often in the previous 6 months.

ANXIETY DISORDER. Uncompleted suicide attempts are made by almost 20 percent of patients with a panic disorder and social phobia. If depression is an associated feature, however, the risk of completed suicide rises.

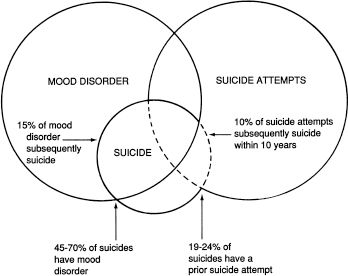

Previous Suicidal Behavior. A past suicide attempt is perhaps the best indicator that a patient is at increased risk of suicide. Studies show that about 40 percent of depressed patients who commit suicide have made a previous attempt. The risk of a second suicide attempt is highest within 3 months of the first attempt. The relation between a mood disorder, completed suicide, and attempts at suicide is shown in Figure 23.1-1.

FIGURE 23.1-1

Venn diagram summarizing suicide data and its relation to mood disorder and suicide attempts. (Courtesy of Alec Roy, M.D.)

Depression is associated with both completed suicide and serious attempts at suicide. The clinical feature most often associated with the seriousness of the intent to die is a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. This is shown by studies that relate the clinical characteristics of suicidal patients with various measures of the medical seriousness of the attempt or of the intent to die. Also, intent-to-die scores correlate significantly with both suicide risk scores and the number and severity of depressive symptoms. Patients having high suicide intent are more often male, older, single or separated, and living alone than those with low intent. In other words, depressed patients who seriously attempt suicide more closely resemble suicide victims than they do suicide attempters.

ETIOLOGY

Sociological Factors

Durkheim’s Theory. The first major contribution to the study of the social and cultural influences on suicide was made at the end of the 19th century by the French sociologist Emile Durkheim. In an attempt to explain statistical patterns, Durkheim divided suicides into three social categories: egoistic, altruistic, and anomic. Egoistic suicide applies to those who are not strongly integrated into any social group. The lack of family integration explains why unmarried persons are more vulnerable to suicide than married ones and why couples with children are the best protected group. Rural communities have more social integration than urban areas and, thus, fewer suicides. Protestantism is a less cohesive religion than Roman Catholicism, and so Protestants have a higher suicide rate than Catholics.

Altruistic suicide applies to those susceptible to suicide stemming from their excessive integration into a group, with suicide being the outgrowth of the integration—for example, a Japanese soldier who sacrifices his life in battle. Anomic suicide applies to persons whose integration into society is disturbed so that they cannot follow customary norms of behavior. Anomie explains why a drastic change in economic situation makes persons more vulnerable than they were before their change in fortune. In Durkheim’s theory, anomie also refers to social instability and a general breakdown of society’s standards and values.

Psychological Factors

Freud’s Theory. Sigmund Freud offered the first important psychological insight into suicide. He described only one patient who made a suicide attempt, but he saw many depressed patients. In his paper “Mourning and Melancholia,” Freud stated his belief that suicide represents aggression turned inward against an introjected, ambivalently cathected love object. Freud doubted that there would be a suicide without an earlier repressed desire to kill someone else.

Menninger’s Theory. Building on Freud’s ideas, Karl Menninger, in Man against Himself, conceived of suicide as inverted homicide because of a patient’s anger toward another person. This retroflexed murder is either turned inward or used as an excuse for punishment. He also described a self-directed death instinct (Freud’s concept of Thanatos) plus three components of hostility in suicide: the wish to kill, the wish to be killed, and the wish to die.

Recent Theories. Contemporary suicidologists are not persuaded that a specific psychodynamic or personality structure is associated with suicide. They believe that much can be learned about the psychodynamics of suicidal patients from their fantasies about what would happen and what the consequences would be if they commit suicide. Such fantasies often include wishes for revenge, power, control, or punishment; atonement, sacrifice, or restitution; escape or sleep; rescue, rebirth, reunion with the dead; or a new life. The suicidal patients most likely to act out suicidal fantasies may have lost a love object or received a narcissistic injury, may experience overwhelming affects like rage and guilt, or may identify with a suicide victim. Group dynamics underlie mass suicides such as those at Masada, at Jonestown, and by the Heaven’s Gate cult.

Depressed persons may attempt suicide just as they appear to be recovering from their depression. A suicide attempt can cause a long-standing depression to disappear, especially if it fulfills a patient’s need for punishment. Of equal relevance, many suicidal patients use a preoccupation with suicide as a way of fighting off intolerable depression and a sense of hopelessness. A study by Aaron Beck showed that hopelessness was one of the most accurate indicators of long-term suicidal risk.

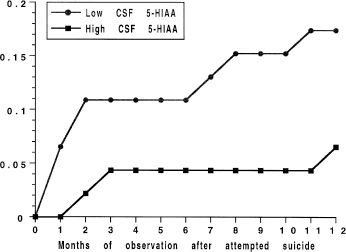

Biological Factors. Diminished central serotonin plays a role in suicidal behavior. A group at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden first noted that low concentrations of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in the lumbar cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were associated with suicidal behavior. This finding has been replicated many times and in different diagnostic groups. Postmortem neurochemical studies have reported modest decreases in serotonin itself or 5-HIAA in either the brainstem or the frontal cortex of suicide victims. Postmortem receptor studies have reported significant changes in presynaptic and postsynaptic serotonin binding sites in suicide victims. Together, these CSF, neurochemical, and receptor studies support the hypothesis that reduced central serotonin is associated with suicide. Recent studies also report some changes in the noradrenergic system of suicide victims.

Low concentrations of 5-HIAA in CSF also predict future suicidal behavior. For example, the Karolinska group examined completed suicide in a sample of 92 depressed patients who had attempted suicide. They found that 8 of the 11 patients who committed suicide within 1 year belonged to the subgroup with below-median concentrations of 5-HIAA in CSF. The suicide risk in that subgroup was 17 percent, compared with 7 percent among those with above-median concentrations of 5-HIAA in CSF (Fig. 23.1-2). Also, the cumulative number of patient-months survived during the first year after attempted suicide was significantly lower in the subgroup with low 5-HIAA concentrations. The Karolinska group concluded that low 5-HIAA concentrations in CSF predict short-range suicide risk in the high-risk group of depressed patients who have attempted suicide. Low 5-HIAA concentrations in CSF have also been demonstrated in adolescents who kill themselves.

FIGURE 23.1-2

Cumulative suicide risk during first year after attempted suicide in patients with low versus high cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA). Filled circles indicate CSF 5-HIAA concentrations below the sample median and filled squares indicate concentrations above the sample median (87 nM). (From Nördstrom P, Samuelsson M, Asberg M, Träskman-Bendz L, Aberg-Wistedt A, Nordin C, Bertilsson L. CSF concentrations 5-HIAA predicts suicide risk after attempted suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994;24:1, with permission.)

Genetic Factors. Suicidal behavior, as with other psychiatric disorders, tends to run in families. In psychiatric patients, a family history of suicide increases the risk of attempted suicide and that of completed suicide in most diagnostic groups. In medicine, the strongest evidence for involvement of genetic factors comes from twin and adoption studies and from molecular genetics. Such studies in suicide are reviewed below.

Twin Studies. A landmark study in 1991 investigated 176 twin pairs in which one twin had committed suicide. In nine of these twin pairs, both twins had committed suicide. Seven of these nine pairs concordant for suicide were found among the 62 monozygotic pairs, whereas two pairs concordant for suicide were found among the 114 dizygotic twin pairs. This twin group difference for concordance for suicide (11.3 vs. 1.8 percent) is statistically significant (P <.01).

Another study collected a group of 35 twin pairs in which one twin had committed suicide and the living co-twin was interviewed. Ten of the 26 living monozygotic cotwins had themselves attempted suicide, compared with 0 of the 9 living dizygotic cotwins (P <.04). Although monozygotic and dizygotic twins may have some differing developmental experiences, these results show that monozygotic twin pairs have significantly higher concordance for both suicide and attempted suicide, which suggests that genetic factors may play a role in suicidal behavior.

Danish-American Adoption Studies. The strongest evidence suggesting the presence of genetic factors in suicide comes from adoption studies carried out in Denmark. A screening of the registers of causes of death revealed that 57 of 5,483 adoptees in Copenhagen eventually committed suicide. They were matched with adopted controls. Searches of the causes of death revealed that 12 of the 269 biological relatives of these 57 adopted suicide victims had themselves committed suicide, compared with only 2 of the 269 biological relatives of the 57 adopted controls. This is a highly significant difference for suicide between the two groups of relatives. None of the adopting relatives of either the suicide or control group had committed suicide.

In a further study of 71 adoptees with mood disorder, adoptee suicide victims with a situational crisis or impulsive suicide attempt or both (particularly) had more biological relatives who had committed suicide than controls had. This led to the suggestion that a genetic factor lowering the threshold for suicidal behavior may lead to an inability to control impulsive behavior. Psychiatric disorders or environmental stress may serve “as potentiating mechanisms which foster or trigger the impulsive behavior, directing it toward a suicidal outcome.”

Molecular Genetic Studies. Tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) is an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of serotonin. A polymorphism in the human TPH gene has been identified, with two alleles—U and L. Because low concentrations of 5-HIAA in CSF are associated with suicidal behavior, it was hypothesized that such individuals may have alterations in genes controlling serotonin synthesis and metabolism. It was found that impulsive alcoholics, who had low CSF 5-HIAA concentrations, had more LL and UL genotypes. Furthermore, a history of suicide attempts was significantly associated with TPH genotype in all the violent alcoholics; 34 of the 36 violent subjects who attempted suicide had either the UL or LL genotype. Thus, it was concluded that the presence of the L allele was associated with an increased risk of suicide attempts.

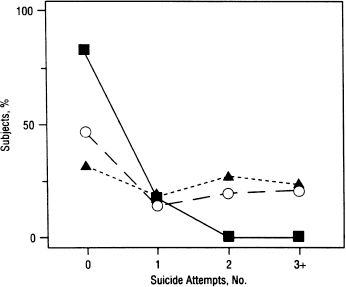

Also, a history of multiple suicide attempts was found most often in subjects with the LL genotype and to a lesser extent among those with the UL genotype (Fig. 23.1-3). This led to the suggestion that the L allele was associated with repetitive suicidal behavior. The presence of one TPH*L allele may indicate a reduced capacity to hydroxylate tryptophan to 5-hydroxytryptophan in the synthesis of serotonin, producing low central serotonin turnover and, thus, a low concentration of 5-HIAA in CSF.

FIGURE 23.1-3

Relation between tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) genotype and lifetime history of multiple suicide attempts. For each genotype, the fraction of subjects having each genotype (UU, squares; UL, circles; LL, triangles) is plotted against the number of suicide attempts they have made in their lives. (From Nielsen D, Goldman D, Virkkunen M, Tokola R, Rawlings R, Linnoila M. Suicidality and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentration associated with a tryptophan hydroxylase polymorphism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:34, with permission.)

Parasuicidal Behavior. Parasuicide is a term introduced to describe patients who injure themselves by self-mutilation (e.g., cutting the skin), but who usually do not wish to die. Studies show that about 4 percent of all patients in psychiatric hospitals have cut themselves; the female-to-male ratio is almost 3 to 1. The incidence of self-injury in psychiatric patients is estimated to be more than 50 times that in the general population. Psychiatrists note that so-called cutters have cut themselves over several years. Self-injury is found in about 30 percent of all abusers of oral substances and 10 percent of all intravenous users admitted to substance-treatment units.

These patients are usually in their 20s and may be single or married. Most cut delicately, not coarsely, usually in private with a razor blade, knife, broken glass, or mirror. The wrists, arms, thighs, and legs are most commonly cut; the face, breasts, and abdomen are cut infrequently. Most persons who cut themselves claim to experience no pain and give reasons for this behavior such as anger at themselves or others, relief of tension, and the wish to die. Most are classified as having personality disorders and are significantly more introverted, neurotic, and hostile than controls. Alcohol abuse and other substance abuse are common, and most cutters have attempted suicide. Self-mutilation has been viewed as localized self-destruction, with mishandling of aggressive impulses caused by a person’s unconscious wish to punish himself or herself or an introjected object.

PREDICTION

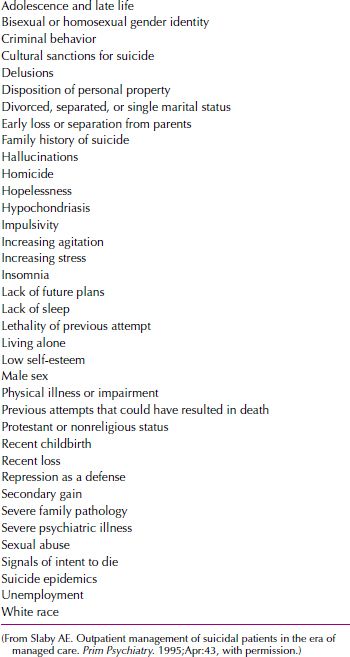

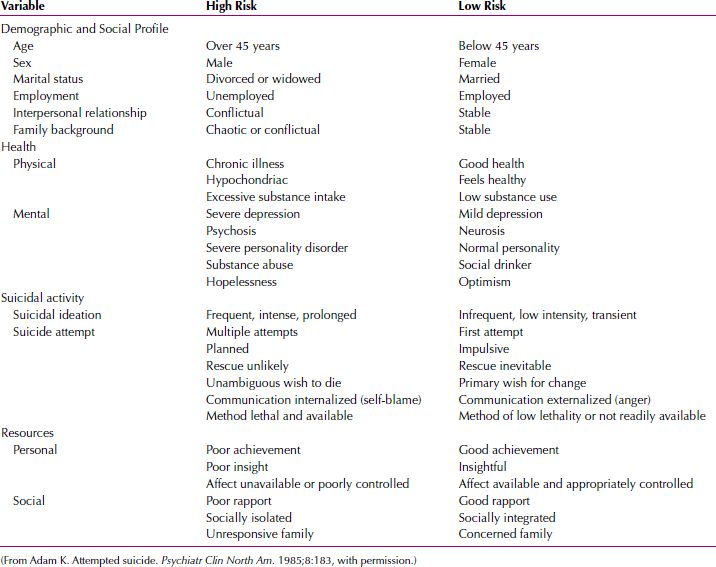

Clinicians must assess an individual patient’s risk for suicide on the basis of a clinical examination. The predictive items associated with suicide risk are listed in Table 23.1-2. Suicide is grouped into high-risk–related and low-risk–related factors (Table 23.1-3). High-risk characteristics include more than 45 years of age, male gender, alcohol dependence (the suicide rate is 50 times higher in alcohol-dependent persons than in those who are not alcohol dependent), violent behavior, previous suicidal behavior, and previous psychiatric hospitalization.

Table 23.1-2

Table 23.1-2

Variables Enhancing Risk of Suicide among Vulnerable Groups

Table 23.1-3

Table 23.1-3

Evaluation of Suicide Risk

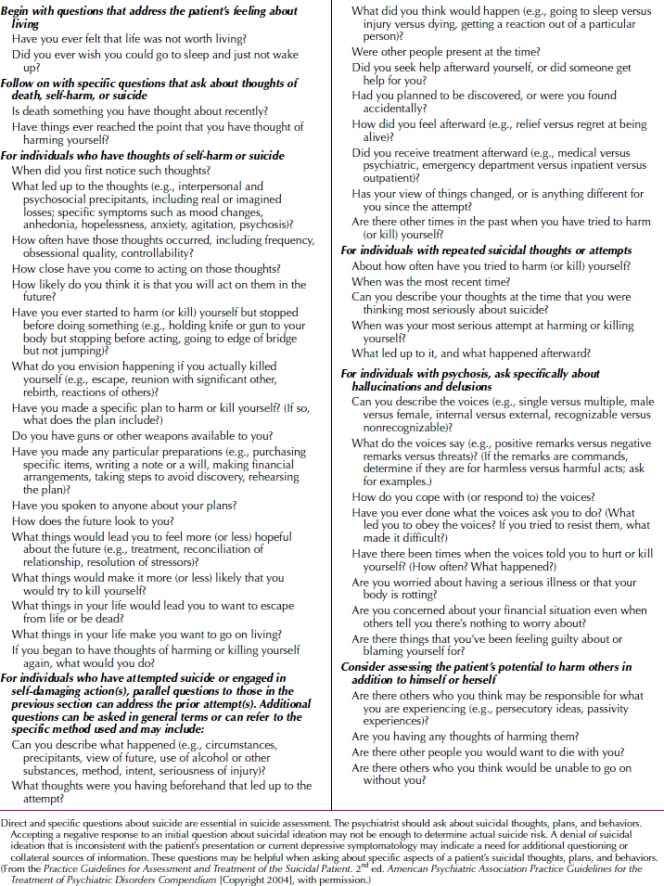

It is important that questions about suicidal feelings and behaviors be asked, often directly. Asking depressed patients whether or not they have had thoughts of wanting to kill themselves does not plant the seed of suicide. To the contrary, it may be the first opportunity a patient has had to talk about suicidal ideation that may have been present for some time.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) developed practice guidelines for treating patients with suicidal behaviors, and Table 23.1-4 lists a host of questions that can help the clinician assess suicide risk.

Table 23.1-4

Table 23.1-4

Questions about Suicidal Feelings and Behaviors

Treatment

Most suicides among psychiatric patients are preventable, because evidence indicates that inadequate assessment or treatment is often associated with suicide. Some patients experience suffering so great and intense, or so chronic and unresponsive to treatment, that their eventual suicides may be perceived as inevitable. Such patients are relatively uncommon, however (see discussion of inevitable suicide below). Other patients have severe personality disorders, are highly impulsive, and commit suicide spontaneously, often when dysphoric, intoxicated, or both.

The evaluation for suicide potential involves a complete psychiatric history; a thorough examination of the patient’s mental state; and an inquiry about depressive symptoms, suicidal thoughts, intents, plans, and attempts. A lack of future plans, giving away personal property, making a will, and having recently experienced a loss all imply increased risk of suicide. The decision to hospitalize a patient depends on diagnosis, depression severity and suicidal ideation, the patient’s and the family’s coping abilities, the patient’s living situation, availability of social support, and the absence or presence of risk factors for suicide.

Inpatient versus Outpatient Treatment

Whether to hospitalize patients with suicidal ideation is the most important clinical decision to be made. Not all such patients require hospitalization; some can be treated on an outpatient basis. But the absence of a strong social support system, a history of impulsive behavior, and a suicidal plan of action are indications for hospitalization. To decide whether outpatient treatment is feasible, clinicians should use a straightforward clinical approach: Ask patients who are considered suicidal to agree to call when they become uncertain about their ability to control their suicidal impulses. Patients who can make such an agreement with a doctor with whom they have a relationship reaffirm the belief that they have sufficient strength to control such impulses and to seek help.

In return for a patient’s commitment, clinicians should be available to the patient 24 hours a day. If a patient who is considered seriously suicidal cannot make the commitment, immediate emergency hospitalization is indicated; both the patient and the patient’s family should be so advised. If, however, the patient is to be treated on an outpatient basis, the therapist should note the patient’s home and work telephone numbers for emergency reference; occasionally, a patient hangs up unexpectedly during a late night call or gives only a name to the answering service. If the patient refuses hospitalization, the family must take the responsibility to be with the patient 24 hours a day.

According to Edwin S. Shneidman, a clinician has several practical preventive measures for dealing with a suicidal person: reducing the psychological pain by modifying the patient’s stressful environment, enlisting the aid of the spouse, the employer, or a friend; building realistic support by recognizing that the patient may have a legitimate complaint; and offering alternatives to suicide.

Many psychiatrists believe that any patient who has attempted suicide, despite its lethality, should be hospitalized. Although most of these patients voluntarily enter a hospital, the danger to self is one of the few clear-cut indications currently acceptable in all states for involuntary hospitalization. In a hospital, patients can receive antidepressant or antipsychotic medications as indicated; individual therapy, group therapy, and family therapy are available, and patients receive the hospital’s social support and sense of security. Other therapeutic measures depend on patients’ underlying diagnoses. For example, if alcohol dependence is an associated problem, treatment must be directed toward alleviating that condition.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree