End-of-Life Issues

34.1 Death, Dying, and Bereavement

34.1 Death, Dying, and Bereavement

DEATH AND DYING

Definitions

The terms death and dying require definition: Whereas death may be considered the absolute cessation of vital functions, dying is the process of losing these functions. Dying may also be seen as a developmental concomitant of living, a part of the birth-to-death continuum. Living may entail numerous mini-deaths—the end of growth and its potential, health-compromising illnesses, multiple losses, decreasing vitality and growing dependency with aging, and dying. Dying, and the individual’s awareness of it, imbues humans with values, passions, wishes, and the impetus to make the most of time.

Two terms that have been used with increased frequency in recent years refer to the quality of living as death comes near. A good death is one that is free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers and is reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards. A bad death, in contrast, is characterized by needless suffering, a dishonoring of the patient or family’s wishes or values, and a sense among participants or observers that norms of decency have been offended.

Uniform Determination of Death Act. The President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research published its definition of death in 1981. Working with the American Bar Association, the American Medical Association (AMA), and the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, the Commission established that one who has sustained either (1) irretrievable cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions or (2) irretrievable cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem, is dead. Determination of death must be in accordance with accepted medical standards.

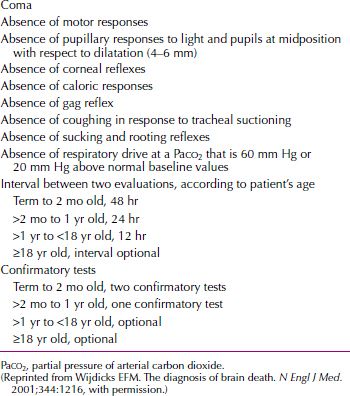

Generally accepted criteria for determining brain death require a series of neurological and other assessments. For children, special guidelines apply. They generally specify two assessments separated by an interval of at least 48 hours for those between the ages of 1 week and 2 months, 24 hours for those between the ages of 2 months and 1 year, and 12 hours for older children; additional confirmatory tests may also be advisable under some circumstances. Brain death criteria are normally not applied to infants younger than 7 days. Table 34.1-1 lists the clinical criteria for brain death in adults and children.

Table 34.1-1

Table 34.1-1

Clinical Criteria for Brain Death in Adults and Children

Legal Aspects of Death

According to law, physicians must sign the death certificate, which attests to the cause of death (e.g., congestive heart failure or pneumonia). They must also attribute the death to natural, accidental, suicidal, homicidal, or unknown causes. A medical examiner, coroner, or pathologist must examine anyone who dies unattended by a physician and perform an autopsy to determine the cause of death. In some cases, a psychological autopsy is performed: A person’s sociocultural and psychological background is examined retrospectively by interviewing friends, relatives, and doctors to determine whether a mental illness, such as a depressive disorder, was present. For example, a determination can be made that a person died because he or she was pushed (murder) or because he or she jumped (suicide) from a high building. Each situation has clear medical and legal implications.

Stages of Death and Dying

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a psychiatrist and thanatologist, made a comprehensive and useful organization of reactions to impending death. A dying patient seldom follows a regular series of responses that can be clearly identified; no established sequence is applicable to all patients. Nevertheless, the following five stages proposed by Kübler-Ross are widely encountered.

Stage 1: Shock and Denial. On being told that they are dying, persons initially react with shock. They may appear dazed at first and then may refuse to believe the diagnosis; they may deny that anything is wrong. Some persons never pass beyond this stage and may go from doctor to doctor until they find one who supports their position. The degree to which denial is adaptive or maladaptive appears to depend on whether a patient continues to obtain treatment even while denying the prognosis. In such cases, physicians must communicate to patients and their families, respectfully and directly, basic information about the illness, its prognosis, and the options for treatment. For effective communication, physicians must allow for patients’ emotional responses and reassure them that they will not be abandoned.

Stage 2: Anger. Persons become frustrated, irritable, and angry at being ill. They commonly ask, “Why me?” They may become angry at God, their fate, a friend, or a family member; they may even blame themselves. They may displace their anger onto the hospital staff members and the doctor, whom they blame for the illness. Patients in the stage of anger are difficult to treat. Doctors who have difficulty understanding that anger is a predictable reaction and is really a displacement may withdraw from patients or transfer them to other doctors’ care.

Physicians treating angry patients must realize that the anger being expressed cannot be taken personally. An empathic, nondefensive response can help defuse patients’ anger and can help them refocus on their own deep feelings (e.g., grief, fear, loneliness) that underlie the anger. Physicians should also recognize that anger may represent patients’ desire for control in a situation in which they feel completely out of control.

Stage 3: Bargaining. Patients may attempt to negotiate with physicians, friends, or even God; in return for a cure, they promise to fulfill one or many pledges, such as giving to charity and attending church regularly. Some patients believe that if they are good (compliant, nonquestioning, cheerful), the doctor will make them better. The treatment of such patients involves making it clear that they will be taken care of to the best of the doctor’s abilities and that everything that can be done will be done, regardless of any action or behavior on the patients’ part. Patients must also be encouraged to participate as partners in their treatment and to understand that being a good patient means being as honest and straightforward as possible.

Stage 4: Depression. In the fourth stage, patients show clinical signs of depression—withdrawal, psychomotor retardation, sleep disturbances, hopelessness, and, possibly, suicidal ideation. The depression may be a reaction to the effects of the illness on their lives (e.g., loss of a job, economic hardship, helplessness, hopelessness, and isolation from friends and family), or it may be in anticipation of the loss of life that will eventually occur. A major depressive disorder with vegetative signs and suicidal ideation may require treatment with antidepressant medication or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). All persons feel some sadness at the prospect of their own death, and normal sadness does not require biological intervention. But major depressive disorder and active suicidal ideation can be alleviated and should not be accepted as normal reactions to impending death. A person who suffers from major depressive disorder may be unable to sustain hope, which can enhance the dignity and quality of life and even prolong longevity. Studies have shown that some terminally ill patients can delay their death until after a loved one’s significant event, such as graduation of a grandson from college.

Stage 5: Acceptance. In the stage of acceptance, patients realize that death is inevitable, and they accept the universality of the experience. Their feelings can range from a neutral to a euphoric mood. Under ideal circumstances, patients resolve their feelings about the inevitability of death and can talk about facing the unknown. Those with strong religious beliefs and a conviction of life after death sometimes find comfort in the ecclesiastical maxim, “Fear not death; remember those who have gone before you and those who will come after.”

Near-Death Experiences

Near-death descriptions are often strikingly similar, involving an out-of-body experience of viewing one’s body and overhearing conversations, feelings of peace and quiet, hearing a distant noise, entering a dark tunnel, leaving the body behind, meeting dead loved ones, witnessing beings of light, returning to life to complete unfinished business, and a deep sadness on leaving this new dimension. This pattern of sensations and perceptions is usually described as peaceful and loving; it feels real to participants, who distinguish it from dreams or hallucinations. These experiences provoke sweeping lifestyle changes, such as fewer material concerns, a heightened sense of purpose, a belief in God, joy of life, compassion, less fear of death, an enhanced approach to life, and intense feelings of love. In a similar vein, hospice nurses have described experiences among terminally ill patients of visions that may include a sense of presence of departed loved ones, of spiritual beings, of a bright light, or of being in a particular place, often described with a sense of warmth and love. Although such “visions” do not readily lend themselves to scientific investigation and thus are not legitimized, patients may benefit from discussing them with clinicians. A term to describe this experience is unio mystica, which refers to an oceanic feeling of mystic unity with an infinite power.

Life Cycle Considerations about Death and Dying

The clinical diversity of death-related attitudes and behaviors between children and adults has its roots in developmental factors and age-dependent differences in causes of death. As opposed to adults, who usually die from chronic illness, children are apt to die from sudden, unexpected causes. Almost half of the children who die between the ages of 1 and 14 years and nearly 75 percent of those who die in late adolescence and early adulthood die from accidents, homicides, and suicides. With their characteristics of violence, suddenness, and mutilation, such unnatural causes of death are special stressors for grieving survivors. Bereaved parents and siblings of dead young children and teenagers often feel victimized and traumatized by their losses; their grief reactions resemble posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Devastating family disruptions can occur, and surviving siblings risk having their emotional needs put on the back burner, ignored, or completely unnoticed.

Children. Children’s attitudes toward death mirror their attitudes toward life. Although they share with adolescents, adults, and elderly adults similar fears, anxieties, beliefs, and attitudes about dying, some of their interpretations and reactions are age specific. None welcome it without ambivalence, and all temper their acceptance with healthy doses of denial and avoidance. Dying children are often aware of their condition and want to discuss it. They often have more sophisticated views about dying than their medically well counterparts, engendered by their own failing health, separations from parents, subjection to painful procedures, and the deaths of hospital chums.

At the preschool, preoperational stage of cognitive development, death is seen as a temporary absence, incomplete and reversible, like departure or sleep. Separation from the primary caretaker(s) is the main fear of preschool-age children. This fear surfaces as an increase in nightmares, more aggressive play, or concern about the deaths of others rather than in direct discourse. Terminally ill children may assume responsibility for their death, feeling guilty for dying. Preschool children may be unable to relate the treatment to the illness, instead viewing treatment as punishment and family separation as rejection. They need reassurance that they are loved, have done nothing wrong, are not responsible for their illness, and will not be abandoned.

School-age children manifest concrete-operational thinking and recognize death as a final reality. They, however, view death as something that happens to old people, not to them. Between the ages of 6 and 12 years, children have active fantasies of violence and aggression, often dominated by themes of death and killing. School-age children ask questions about serious illness and death if encouraged to do so; however, if they receive cues that the subject is taboo, they may withdraw and participate less fully in their care. Facilitating open discussion and updating children with important information, including prognostic changes, can be very helpful. In addition, children may need help coping with peers and school demands. Teachers should be informed and updated. Classmates may need education and assistance to help them understand the situation and respond appropriately.

Adolescents. Capable of formal cognitive operations, adolescents understand that death is inevitable and final but may not accept that their own death is possible. The major fears of dying teenagers parallel those of all teenagers—losing control, being imperfect, and being different. Concerns about body image, hair loss, or loss of bodily control can generate great resistance to continuing treatment. Alternating emotions of despair, rage, grief, bitterness, numbness, terror, and joy are common. The potential for withdrawal and isolation is great because teenagers may equate parental support with loss of independence or may deny their fears of abandonment by actually repulsing friendly gestures. Teenagers must be included in all decision-making processes surrounding their deaths. Many are capable of great courage, grace, and dignity in facing death.

Adults. Some of the most often expressed fears of adult patients entering hospice care, listed in the approximate order of frequency, include fears of (1) separation from loved ones, homes, and jobs; (2) becoming a burden to others; (3) losing control; (4) what will happen to dependents; (5) pain or other worsening symptoms; (6) being unable to complete life tasks or responsibilities; (7) dying; (8) being dead; (9) the fears of others (reflected fears); (10) the fate of the body; and (11) the afterlife. Problems in communication arise out of trepidation, making it important for those involved in health care to provide environments of trust and safety in which people can begin to talk about uncertainties, anxieties, and concerns.

Late-age adults often accept that their time has come. Their main fears include long, painful, and disfiguring deaths; prolonged vegetative states; isolation; and loss of control or dignity. Elderly patients may talk or joke openly about dying and sometimes welcome it. In their 70s and beyond, they rarely harbor illusions of indestructibility—most have already had several close calls: Their parents have died, and they have gone to funerals for friends and relatives. Although they may not be happy to die, they can be reconciled to it.

According to Erik Erikson, the eighth and final stage in the life cycle brings a sense of either integrity or despair. As elderly adults enter the last phase of their lives, they reflect on their pasts. When they have taken care of their affairs, have been relatively successful, and have adapted to the triumphs and disappointments of life, they can look back with satisfaction and only a few regrets. Integrity of the self allows people to accept inevitable disease and death without fear of succumbing helplessly. If elderly individuals look back on life as a series of missed opportunities or personal misfortunes, however, they feel a sense of bitter despair, a preoccupation with what might have been if only this or that had happened. Then death is fearsome because it symbolizes emptiness and failure.

Management

Caring for a dying patient is highly individual. Caretakers need to deal with death honestly, tolerate wide ranges of affects, connect with suffering patients and bereaved loved ones, and resolve routine issues as they arise. Although each therapeutic relationship between a patient and health provider has a uniqueness derived from the patient’s and health provider’s gender, constitution, life experience, age, stage of life, resources, faith, culture, and other considerations, major themes confront all health providers caring for dying patients. End-of-life care and palliative medicine are discussed in Section 34.2.

BEREAVEMENT, GRIEF, AND MOURNING

Bereavement, grief, and mourning are terms that apply to the psychological reactions of those who survive a significant loss. Grief is the subjective feeling precipitated by the death of a loved one. The term is used synonymously with mourning, although, in the strictest sense, mourning is the process by which grief is resolved; it is the societal expression of postbereavement behavior and practices. Bereavement literally means the state of being deprived of someone by death and refers to being in the state of mourning. Regardless of the fine points that differentiate these terms, the experiences of grief and bereavement have sufficient similarities to warrant a syndrome that has signs, symptoms, a demonstrable course, and an expected resolution.

Normal Bereavement Reactions

The first response to loss, protest, is followed by a longer period of searching behavior. As hope to reestablish the attachment bond diminishes, searching behaviors give way to despair and detachment before bereaved individuals eventually reorganize themselves around the recognition that the lost person will not return. Although the bereaved ultimately learn to accept the reality of the death, they also find psychological and symbolic ways of keeping the memory of the deceased person very much alive. Grief work allows the survivor to redefine his or her relationship to the deceased person and to form new but enduring ties.

Duration of Grief. Most societies mandate modes of bereavement and time for grieving. In contemporary America, bereaved individuals are expected to return to work or school in a few weeks, to establish equilibrium within a few months, and to be capable of pursuing new relationships within 6 months to 1 year. Ample evidence suggests that the bereavement process does not end within a prescribed interval; certain aspects persist indefinitely for many otherwise high-functioning, normal individuals.

The most lasting manifestation of grief, especially after spousal bereavement, is loneliness. Often present for years after the death of a spouse, loneliness may, for some, be a daily reminder of the loss. Other common manifestations of protracted grief occur intermittently. For example, a man who has lost his wife may experience elements of acute grief every time he hears her name or sees her picture on the nightstand. Usually, these reactions become increasingly short lived over time, dissipating within minutes, and become tinged with positive and pleasant affects. Such bittersweet memories may last a lifetime. Thus, most grief does not fully resolve or permanently disappear; rather, grief becomes circumscribed and submerged only to reemerge in response to certain triggers.

Anticipatory Grief

In anticipatory grief, grief reactions are brought on by the slow dying process of a loved one through injury, illness, or high-risk activity. Although anticipatory grief may soften the blow of the eventual death, it can also lead to premature separation and withdrawal while not necessarily mitigating later bereavement. At times, the intensification of intimacy during this period may heighten the actual sense of loss even though it prepares the survivor in other ways.

Anniversary Reactions. When the trigger for an acute grief reaction is a special occasion, such as a holiday or birthday, the rekindled grief is called an anniversary reaction. It is not unusual for anniversary reactions to occur each year on the same day the person died or, in some cases, when the bereaved individual becomes the same age the deceased person was at the time of death. Although these anniversary reactions tend to become relatively mild and brief over time, they can be experienced as the reliving of one’s original grief and prevail for hours or days.

Mourning

From earliest history, every culture records its own beliefs, customs, and behaviors related to bereavement. Specific patterns include rituals for mourning (e.g., wakes or Shiva), for disposing of the body, for invocation of religious ceremonies, and for periodic official remembrances. The funeral is the prevailing public display of bereavement in contemporary North America. The funeral and burial service acknowledge the real and final nature of the death, countering denial; they also garner support for the bereaved, encouraging tribute to the dead, uniting families, and facilitating community expressions of sorrow. If cremation replaces burial, ceremonies associated with dissemination of the ashes perform similar functions. Visits, prayers, and other ceremonies allow for continuing support, coming to terms with reality, remembering, emotional expression, and concluding unfinished business with the deceased. Several cultural and religious rituals provide purpose and meaning, protect the survivors from isolation and vulnerability, and set limits on grieving. Subsequent holidays, birthdays, and anniversaries serve to remind the living of the dead and may elicit grief as real and fresh as the original experience; over time, these anniversary grievings become attenuated but often remain in some form.

Bereavement

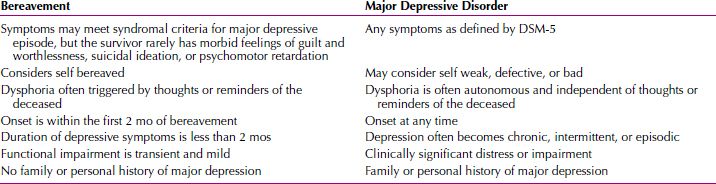

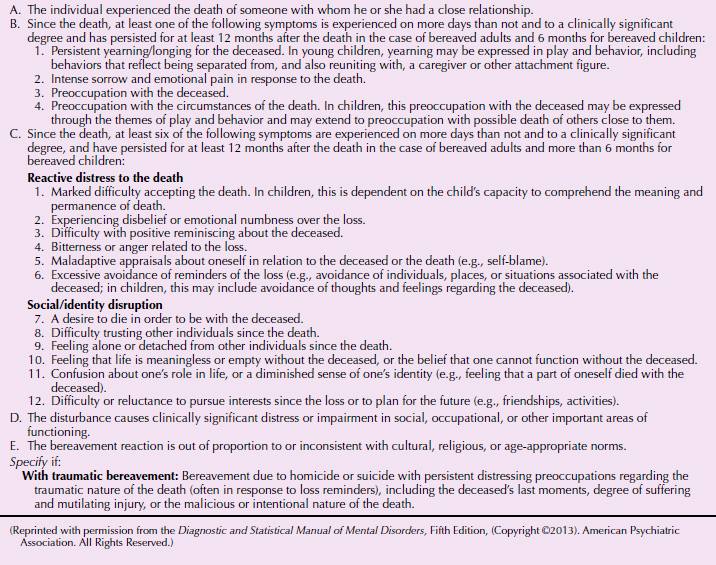

Because bereavement often evokes depressive symptoms, it may be necessary to demarcate normal grief reactions from major depressive disorder (Table 34.1-2). In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a new condition has been proposed for further study called persistent complex bereavement disorder to account for bereavement that lasts for more than 1 year (Table 34.1-3). This disorder may resemble symptoms of a major depressive episode, which is characterized by severe functional impairment and includes morbid preoccupation with worthlessness, suicidal ideation, psychotic symptoms, or psychomotor retardation. This is discussed further below.

Table 34.1-2

Table 34.1-2

Differentiating the Depressive Symptoms Associated with Bereavement from Major Depression

Table 34.1-3

Table 34.1-3

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder

Complicated Bereavement

Complicated bereavement has a confusing array of terms to describe it—abnormal, atypical, distorted, morbid, traumatic, and unresolved, to name a few types. Three patterns of complicated, dysfunctional grief syndromes have been identified—chronic, hypertrophic, and delayed grief. These are not diagnostic categories within DSM-5 but are descriptive syndromes that, if present, may be prodromata of a major depressive disorder.

Chronic Grief. The most common type of complicated grief is chronic grief, often highlighted by bitterness and idealization of the dead person. Chronic grief is most likely to occur when the relationship between the bereaved and the deceased had been extremely close, ambivalent, or dependent or when social supports are lacking and friends and relatives are not available to share the sorrow over the extended period of time needed for most mourners.

Hypertrophic Grief. Most often seen after a sudden and unexpected death, bereavement reactions are extraordinarily intense in hypertrophic grief. Customary coping strategies are ineffectual to mitigate anxiety, and withdrawal is frequent. When one family member is experiencing a hypertrophic grief reaction, disruption of family stability can occur. Hypertrophic grief frequently takes on a long-term course, albeit one attenuated over time.

Delayed Grief. Absent or inhibited grief when one normally expects to find overt signs and symptoms of acute mourning is referred to as delayed grief. This pattern is marked by prolonged denial; anger and guilt may complicate its course.

Traumatic Bereavement. Traumatic bereavement refers to grief that is both chronic and hypertrophic. This syndrome is characterized by recurrent, intense pangs of grief with persistent yearning, pining, and longing for the deceased; recurrent intrusive images of the death; and a distressing admixture of avoidance and preoccupation with reminders of the loss. Positive memories are often blocked or excessively sad, or they are experienced in prolonged states of reverie that interfere with daily activities. A history of psychiatric illness appears to be common in this condition, as is a very close, identity-defining relationship with the deceased person.

Medical or Psychiatric Illnesses Associated with Bereavement. Medical complications include exacerbations of existing diseases and vulnerability to new ones; fear for one’s health and more trips to the doctor; and an increased mortality rate, especially in men. The highest relative mortality risk is found immediately after bereavement, particularly from ischemic heart disease. The greatest effect of bereavement on mortality is for men younger than 65 years. Higher mortality rates in bereaved men than in bereaved women are due to increases in the relative risk of death by suicide, accident, cardiovascular disease, and some infectious diseases. In widows, the relative risk of death from cirrhosis and suicide may increase. In both sexes, bereavement appears to exacerbate health-compromising behaviors, such as increased alcohol consumption, smoking, and the use of over-the-counter medications.

Psychiatric complications of bereavement include an increased risk for major depressive disorder, prolonged anxiety, panic, and a posttraumatic stress–like syndrome; increased alcohol, drug, and cigarette consumption; and an increased risk of suicide. Because of their psychosocial, emotional, and cognitive immaturity, bereaved children may be especially vulnerable to psychopathology.

Bereavement and Depression. Although symptoms overlap, grief can be distinguished from a full depressive episode. Most bereaved individuals experience intense sadness, but only a few meet DSM-5 criteria for major depressive episode. Grief is a complex experience in which positive emotions take their place beside the negative ones. Grief is fluid and changing, an evolving state in which emotional intensity gradually lessens and positive, comforting aspects of the lost relationship come to the fore. Pangs of grief are stimulus bound, related to internal and external reminders of the deceased person. This differs from depression, which is more pervasive and characterized by much difficulty experiencing self-validating, positive feelings. Grief is a fluctuating state with individual variability, in which cognitive and behavioral adjustments are progressively made until the bereaved individual can hold the deceased person in a comfortable place in memory and a satisfying life can be resumed. By contrast, major depressive episode consists of a recognizable and stable cluster of debilitating symptoms accompanied by a protracted, enduring low mood. Major depressive episode tends to be persistent and associated with poor work and social functioning, pathological psychoneuroimmunological function, and other neurobiological changes, unless treated.

Bereavement and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Unnatural and violent deaths, such as homicide, suicide, or death in the context of terrorism, are much more likely to precipitate PTSD in surviving loved ones than are natural deaths. In such circumstances, themes of violence, victimization, and volition (i.e., the choice of death over life, as in the case of suicide) are intermixed with other aspects of grief, and traumatic distress marked by fear, horror, vulnerability, and disintegration of cognitive assumptions ensues. Disbelief, despair, anxiety symptoms, preoccupation with the deceased person and the circumstances of the death, withdrawal, hyperarousal, and dysphoria are more intense and more prolonged than they are under nontraumatic circumstances, and an increased risk may exist for other complications. Although treatment studies in survivors of sudden death are few and far between, most experts agree that initial attention should be focused on traumatic distress, that a role is seen for both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, and that self-help support groups can be enormously beneficial.

Biological Perspectives

Grief is both a physiological and an emotional response. During acute grief (as with other stressful events), persons may experience disruption of biological rhythms. Grief is also accompanied by impaired immune functioning, including decreased lymphocyte proliferation and impaired functioning of natural killer cells. Whether the immune changes are clinically significant has not been established, but the mortality rate for widows and widowers following the death of a spouse is higher than that in the general population. Widowers appear to be at risk longer than widows.

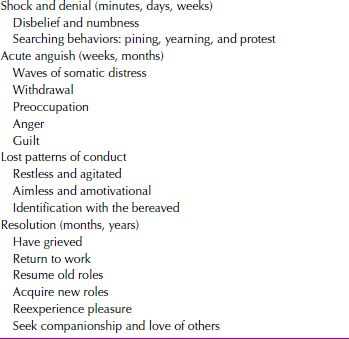

Phenomenology of Grief. Bereavement reactions include intense feeling states; invoke a variety of coping strategies; and lead to alterations in interpersonal relationships, biopsychosocial functioning, self-esteem, and world view that can last indefinitely. Manifestations of grief reflect the individual’s personality, previous life experiences, and past psychological history; the significance of the loss; the nature of the bereaved person’s relationship with the deceased person; the existing social network; intercurrent life events; health; and other resources. Despite individual variations in the bereavement process, investigators have proposed grieving process models, which include at least three partially overlapping phases or states: (1) initial shock, disbelief, and denial; (2) an intermediate period of acute discomfort and social withdrawal; and (3) a culminating period of restitution and reorganization. As with Kübler-Ross’ stages of dying, the grieving stages do not prescribe a correct course of grief; rather, they are general guidelines describing an overlapping and fluid process that varies with the survivors (Table 34.1-4).

Table 34.1-4

Table 34.1-4

Phases of Grief

LIFE CYCLE PERSPECTIVES ABOUT BEREAVEMENT

Bereavement During Childhood and Adolescence

Approximately 4 percent of North American children lose one or both parents by the age of 15 years; sibling death is the second most commonly experienced bereavement. Grief reactions are colored by developmental levels and concepts of death and may not resemble adult reactions. Children may display minimal grief at time of death and experience the full effect of the loss later. Grieving children may not withdraw and dwell on the person who died, but instead, may throw themselves into activities. Indifference, anger, or misbehavior may be displayed rather than sadness; behaviors can be erratic and labile. Strong feelings of anger and fears of abandonment or death may show up in the behavior of grieving children. Children often play death games as a way of working out their feelings and anxieties. These games are familiar to the children and provide safe opportunities to express their feelings. Although they may seem to show grief only occasionally and briefly, in reality, a child’s grief often lasts longer than that of an adult.

Mourning in children may need to be addressed again and again as the child gets older. Children will think about the loss repeatedly, especially during important times in their lives, such as going to camp, graduating from school, getting married, or giving birth to their own children. A child’s grief can be influenced by his or her age, personality, developmental stage, earlier experiences with death, and relationship with the deceased person. The surroundings, cause of death, and family members’ ability to communicate with one another and to continue as a family after the death can also affect grief. The child’s ongoing need for care, his or her opportunity to share feelings and memories, the parent’s ability to cope with stress, and the child’s steady relationships with other adults are other factors that may influence grief. Even older children frequently feel abandoned or rejected when a parent dies and may show hostility toward the deceased or the surviving parent, now perceived as one who might also “abandon” them. They may feel responsible because of earlier misbehavior or because they said or wished that that person would die at some time.

Children younger than 2 years may show loss of speech or diffuse distress. Children younger than 5 years are apt to respond with eating, sleeping, and bowel and bladder dysfunctions. Strong feelings of sadness, fear, and anxiety can occur, but these feelings are not persistent and tend to alternate between longer lasting normal states. School-age children may become phobic or hypochondriacal, withdrawn, or pseudomature, and school performance and peer relations often suffer. Adolescents, as with adults, run the gamut in expressing bereavement, ranging from behavioral problems, somatic symptoms, and erratic moods to stoicism. Whereas adolescent boys losing a parent may become delinquent, girls may turn to a sexual pattern for comfort and reassurance. Behavioral disturbances and depression are common at all ages. Rates of depressive episodes in bereaved children and adolescents are as high as in bereaved adults.

Bereaved children must be treated with respect to their own levels of emotional and cognitive maturity. They need to be told that the death is real and irreversible and that they are blameless. Feelings and concerns should be expressed, and questions should be invited and answered with simplicity, candor, and clarity. Children, as with adults, need rituals to commemorate their loved ones; attendance at the funeral and participation in mourning may be beneficial first steps.

Bereavement During Adulthood

No consensus exists on which type of loss is associated with the most severe reactions. Although the death of a spouse is often ranked as the most stressful life event, some have argued that losing a child is even more profound. The death of a child is a special sorrow, a lifelong loss for surviving mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, grandparents, and other family members. A child’s death is a life-altering experience. The deaths of parents and siblings in adult life have not achieved much systematic study, but they are generally considered relatively mild compared with the loss of a spouse or child.

Grief appears most intense for the mother in late perinatal losses (stillbirths or neonatal deaths rather than miscarriages) and often is reexperienced during subsequent pregnancies. Sudden infant death syndrome is particularly problematic in that the death is sudden and unexpected. Parents may experience extra guilt or blame each other, often resulting in subsequent marital difficulties.

The surviving family members, friends, or lovers of individuals who have died from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are uniquely challenged. The illness carries with it the stigmata of the illness itself and of the gay community in general; it carries with it caretakers’ fears of contracting the illness; and it is most prevalent in people who are in the prime of life. Asymptomatic infection may permit the infected person and those close to him or her time to adapt to the diagnosis. When a person who is human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive begins to manifest symptoms of opportunistic infection or associated cancer, however, the illness again becomes a threat. Coping with the emotional reality is arduous and complex. Often caretakers, as well as HIV-positive patients, wish for death, which can evoke feelings of guilt. For bereaved lovers, their own HIV status, multiple losses, and other concurrent stressors can complicate recovery. Gay men who have lost lovers to AIDS may be more depressed, consider suicide more often, and be more vulnerable to illicit drug use than are other bereaved individuals.

Elderly adults face more losses than individuals at other phases of the life cycle, and intense loneliness may be a lasting memorial to those who have died. For highly impaired elders who lose a spouse they depended on for daily functions or who was their sole source of companionship, bereavement reactions are profound.

Grief Therapy

Persons in normal grief seldom seek psychiatric help because they accept their reactions and behavior as appropriate. Accordingly, a bereaved person should not routinely see a psychiatrist or psychologist unless a markedly divergent reaction to the loss is noted. For example, under usual circumstances, a bereaved person does not make a suicide attempt; if someone seriously contemplates suicide, psychiatric intervention is indicated.

When professional assistance is sought, it usually involves a request for sleeping medication from a family physician. A mild sedative to induce sleep may be useful in some situations, but antidepressant medication or antianxiety agents are rarely indicated in normal grief. Bereaved persons may have to go through the mourning process, however painful it is, for successful resolution to occur. Narcotizing patients with drugs interferes with the normal process that ultimately can lead to a favorable outcome.

Because grief reactions can develop into a depressive disorder or pathological mourning, specific counseling sessions for bereaved individuals are often valuable. Grief therapy is an increasingly important skill. In regularly scheduled sessions, grieving persons are encouraged to talk about feelings of loss and about the person who has died. Many bereaved persons have difficulty recognizing and expressing angry or ambivalent feelings toward a deceased person, and they must be reassured that these feelings are normal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree