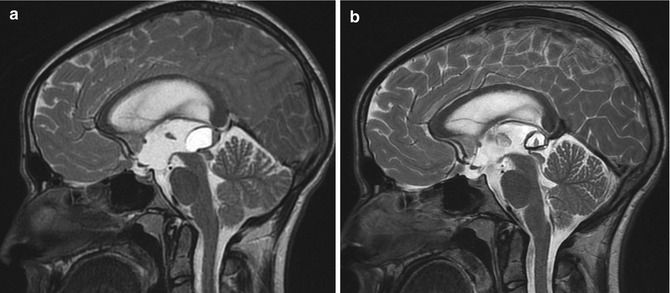

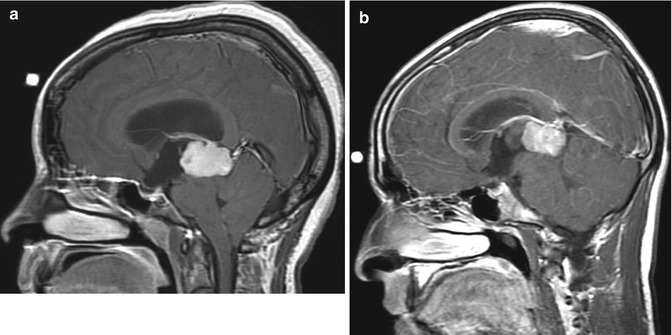

Fig. 10.1

Contrast-enhanced MRI from a patient with a recurrent cystic craniopharyngioma who presented with visual deterioration. The preoperative image (a) demonstrates the large dimension and mass effect from the tumor cyst. The postoperative MRI (b) after a right transventricular endoscopic fenestration reveals the reduction in size and mass effect of the cyst

For most cystic tumors causing obstructive hydrocephalus at the level of the third ventricle, a standard coronal approach is an ideal trajectory. Tumor cysts in the region of the posterior third ventricle, typically being benign mesencephalic tumors, need to be approached from a far-precoronal entry similarly used for biopsy or removal of pineal region tumors (Fig. 10.2).

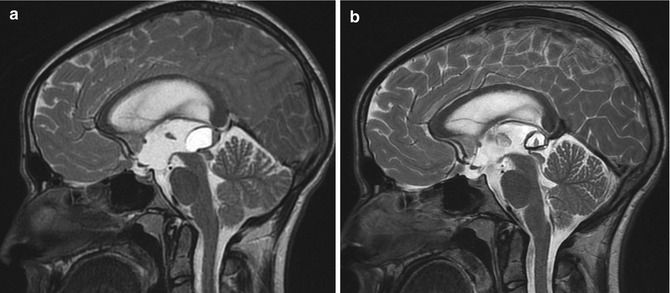

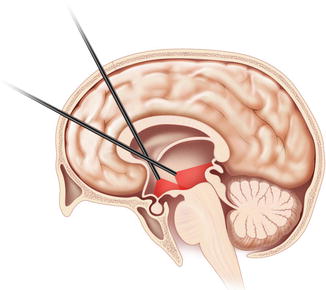

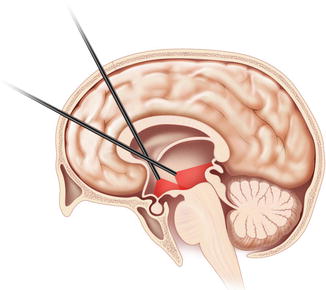

Fig. 10.2

Sagittal T2-weighted MRI before (a) and after (b) endoscopic fenestration of a cystic tumor at the rostral mesencephalon. This adolescent male required no further therapy for a biopsy-proven low-grade glial tumor

Regardless of tumor position, one should attempt to create the largest fenestration possible to reduce any future occlusion of the opening (Fig. 10.3). Unlike a technique used for endoscopic third ventriculostomy, energy sources such as bipolar coagulation or laser are used to generously cut through the tumor cyst membrane. Although rare, inflammatory changes in the CSF from cyst contents are reduced with preoperative corticosteroids and continuous irrigation.

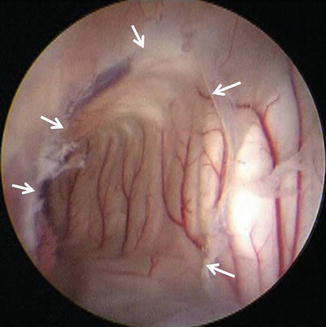

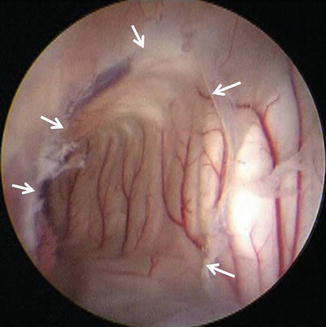

Fig. 10.3

Endoscopic view through a large fenestration created in a cyst of the right lateral ventricle. The wide margins of the fenestration (arrows) minimizes the potential for subsequent occlusion

10.3.2 Tumor Biopsy

Endoscopic tumor biopsy is a well-established method for sampling intraventricular brain tumors. The results of these minimally invasive techniques can have a profound impact on the management of children with intraventricular brain tumors [4–7]. The diagnostic yield is high and the risk is low [8, 9]. In the author’s current series of 80 patients who have undergone endoscopic biopsy, the diagnostic yield was 98 % (78/80 diagnostic samples) with a 1.3 % risk of postoperative permanent neurologic morbidity. Endoscopic tumor biopsy is of particular importance in patients in which the overall oncologic management may not require an aggressive or total tumor removal. Thus, a patient in whom the potential diagnosis includes a germ cell tumor, infiltrative hypothalamic/optic pathway glioma, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis would be an ideal candidate for a minimally invasive endoscopic diagnostic sampling. Given that the majority of these tumor types occur in young patients, age is quite influential in the decision-making process regarding the role of endoscopic tumor biopsy. A patient with a clinical suspicion of CNS germ cell tumor with positive serum tumor markers (βHCG, αAFP) represents a relative contraindication for endoscopic tumor sampling. The tumor morphology also plays a role in assessing the potential for safe endoscopic biopsy. In short, only tumors that exhibit an exophytic component into the ventricle are logical candidates for endoscopic tumor biopsy (Fig. 10.4). Subependymal tumors that do not present into the ventricular system even though they may distort the ventricular walls can be difficult to locate intraoperatively and alternative methods of tumor sapling should be considered.

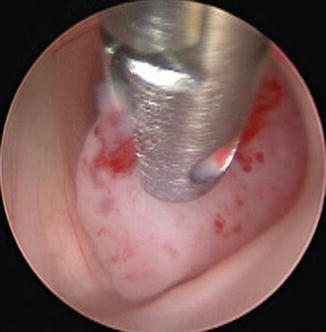

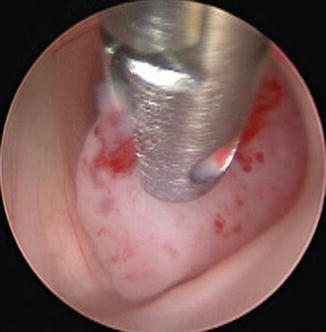

Fig. 10.4

Endoscopic view into the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle demonstrates an ideal tumor for endoscopic biopsy or removal. The tumor is exophytic into the ventricular compartment and distinct from the ependymal surface

Surgical planning with navigational guidance will result in less torque on cortical and subcortical tissues and hence is an important adjunct for endoscopic tumor biopsy [10, 11]. Once the tumor is visualized, cupped biopsy forceps are used to sample the tumor (Fig. 10.5). Sites of sampling are chosen that most likely represent pathologic tissue, are relatively avascular, and require as little torque as possible. The small samples of tissue obtained with cupped forceps are challenging for accurate pathologic interpretation, and every attempt should be made to minimize artifact from electrocautery. Therefore, the use of coagulation on the tumor surface, as logical as that may seem, should be avoided prior to sampling. Varying degrees of venous hemorrhage invariably occur with cupped biopsy forceps. This degree of hemorrhage will typically be controlled with continuous irrigation, balloon tamponade, or electrocautery. The number of samples should be governed by frozen specimen interpretation and no more tissue than is absolutely necessary is taken in an effort to reduce intraventricular hemorrhage.

Fig. 10.5

Cupped biopsy forceps are used for tumor sampling in this posterior third ventricular/pineal region tumor. The tumor is clearly distinguished from the walls of the hypothalamus

10.3.3 Simultaneous Tumor Biopsy and Endoscopic Third Ventriculostomy

The prominence of pineal region tumors in children coupled with the high frequency of tumors that may not necessitate aggressive surgical resection converges nicely with endoscopic applications [12–15]. Notably, primary central nervous system germ cell tumors (CNS GCT), both pure germinomas and nongerminomatous germ cell tumors, can be effectively treated without radical resection. Thus, children who present with noncommunicating hydrocephalus with a pineal region tumor should always be considered for primary endoscopic management by way of ETV and tumor biopsy (Fig. 10.6). Serum biochemical analysis for alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) should always precede endoscopic biopsy since marker-positive GCT should be initially managed with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy.

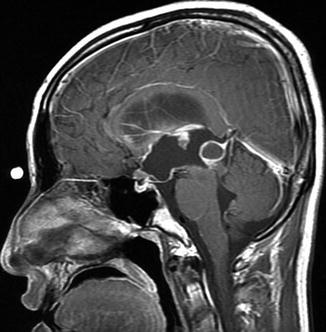

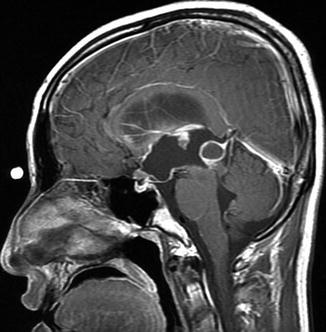

Fig. 10.6

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI after administration of contrast agent reveals a cystic enhancing tumor in the pineal region. This adolescent male who presented with symptoms of hydrocephalus had no detectable serum markers (AFP, HCG) and thus underwent a simultaneous endoscopic third ventriculostomy and tumor biopsy. He was subsequently treated for a pure germinoma with no further surgery

While the child with a pineal region tumor and noncommunicating hydrocephalus represents one of the best surgical candidates for endoscopic surgery, the situation can represent a challenging procedure. Navigating the endoscope into the limited space of the posterior third ventricle and sampling tumors that are variably hemorrhagic contribute toward this challenge. Since the optimal trajectory for ETV (coronal entry) and pineal region tumor biopsy (frontal-precoronal entry) is distinct, a single or dual entry site will need to be chosen if a rod lens endoscope is used (Fig. 10.7). It is advised to choose a technique that best suites the individual patient based upon the ventricular size, the relative position of the tumor, the dimension of the massa intermedia, and the surgical goal. Typically, a combined approach through a single burr hole mandates that the entry site be located midway between the optimal entry sites for either separate procedure. This single approach is best used when the tumor presents anterior to the massa intermedia, when the massa is small, when the degree of ventriculomegaly is severe, or when the tumor size obviates any consideration for total tumor removal. Alternatively, when tumors that are recessed behind the massa intermedia, when the degree of ventriculomegaly is moderate, when tumors may be amenable to total removal (<2 cm), or when the massa intermedia is large, two sites of entry are advocated; one being optimal for the tumor biopsy and the other being optimal for the ETV (Fig. 10.8). Although fiberoptic or steerable endoscopes are ideally suited for this combined procedure, the smaller working channels, the greater potential for disorientation, and the decreased image resolution associated with these endoscopes all have limited their widespread appeal.

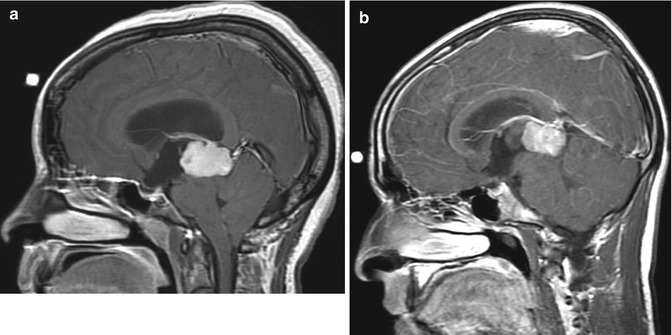

Fig. 10.7

This illustration depicts the ideal and separate trajectories for endoscopic third ventriculostomy (precoronal entry) and a pineal region tumor approach (frontal-precoronal). The use of a single or dual entry is determined by the characteristics of the tumor and the third ventricular anatomy (Illustration provided by Thom Graves of Thom Graves Media, New York, New York.)

Fig. 10.8

Sagittal MRI of two different patients that underwent simultaneous ETV and tumor biopsy for hydrocephalus and a pineal region tumor. Tumors that extend anterior to the massa intermedia in patients with significant ventriculomegaly (a) are good candidates for a single trajectory while smaller tumors or less hydrocephalus (b) may require two different approaches

When performing simultaneous ETV and tumor biopsy, it is preferred to perform the ETV prior to tumor biopsy. This order is advocated since the most pressing clinical condition of noncommunicating hydrocephalus should be definitively addressed prior to any visual potential obscuration by hemorrhage that invariably occurs with tumor biopsy. Thus far, the hypothetical concern of tumor dissemination from the intraventricular compartment to the subarachnoid space following this simultaneous procedure has not been supported by retrospective clinical series [16]. However, metastatic spread of tumor at the endoscopic path has been documented and thus the actual risk of tumor spread remains undefined [17, 18].

10.3.4 Solid Tumor Resection

Solid tumor removal, although a logical application of endoscopic techniques, is somewhat limited due to the inadequacy of compatible instrumentation and the small caliber of current endoscopic portals. The success of endoscopic tumor removal is dependent upon the tumor characteristics including size, density, and vascularity. Tumors larger than 2 cm, those that have appreciable calcification on computed tomography (CT), and those that have significant subependymal infiltration are not currently amenable to endoscopic removal. Variables that can limit complete endoscopic tumor removal are nearly impossible to predict based on current imaging techniques. When a patient is being considered for purely endoscopic tumor removal, noncontrast CT can be used to estimate the degree of mineralization based on the presence or absence of solid calcifications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree