9 Endoscopic Methods in Acoustic Neurinomas

Endoscope-Assisted Microsurgery

Endoscope-Assisted Microsurgery

Clinical Material

Clinical Material

Endoscope-Assisted Microsurgery

Endoscopes have been used in neurosurgery since the beginning of the previous century. Improved technology has from time to time fueled renewed interest in expanding the possible applications of endoscopic methods in neurosurgery. The period from second half of the 1990 s to the present has witnessed a renewed interest in endoscopic applications in spinal and cranial microsurgery. As described in a previous chapter, our experience has led to the use of rigid endoscopes with varied angles of vision. In contrast to semirigid and flexible fiberoptic endoscopes, rigid endoscopes provide better lenses and are significantly easier to handle. Neuroendoscopy provides a completely different optical dimension to what we are accustomed to seeing through the surgical microscope, and requires certain insights into various important aspects of neuroanatomy and adaptations in strategy during the planning and performance of microsurgery procedures. As with any microsurgical procedure or technique that is unfamiliar to the surgeon, a certain amount of practice and rehearsal is always beneficial prior to performing the procedure. The anatomical view we are accustomed to see under the microscope becomes unfamiliar when viewed endoscopically. This apparent alteration of the topography is artificially created by the more restricted view through the endoscope. Another fact that needs to be taken into account is that structures routinely observed, but hardly noticed, through the microscope can take on special importance when seen through the endoscope—particularly arachnoid trabeculae and membranes. The requisite familiarity with the endoscopic view can only be gained through practice and repetition.

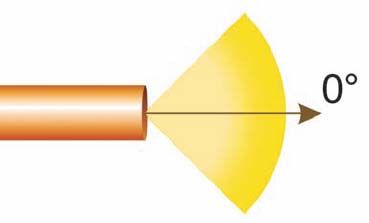

The rigid endoscope with a 0° (nonangled) lens is by far the easiest with regard to handling and recognition of the orientation of view. Angled endoscopes (30° and 70°) are helpful for looking round corners, but add a dimension of uncertainty both when the endoscope is passed out of the direct view of the microscopic field and with regard to orientation. It is important to be sure of the path the endoscope will pass through when using these angled endoscopes (especially the 70° lens system) to avoid damage to structures not seen lying in the instrument’s path.

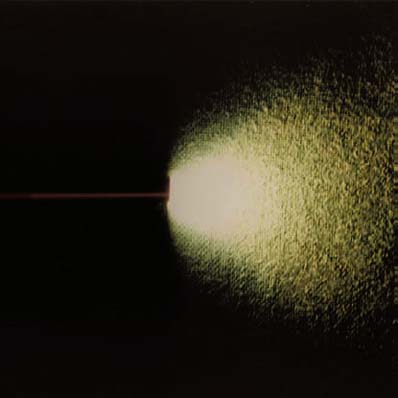

When using these techniques in acoustic neurinoma surgery, one has to bear two major phenomena in mind. The first is an optic phenomenon known as the “fisheye” effect (Fig. 9.1). This refers to the different optical dimension seen through the endoscope, which shows structures through a lens of exaggerated convexity, as if through the eye of a fish. This results in a somewhat distorted view as the edges of the image are approached. The other effect is known as the “scene” phenomenon (Fig. 9.2). This is demonstrated by the case of an actor who stands in front of and faces the audience, not able to see what is behind him on the stage. Moving to either side or backward can result in a collision between the actor and a prop that he or she is unable to visualize when looking forward at the audience. This can happen with the endoscope in the cerebellopontine angle, when the instrument is being maneuvered through restricted apertures.

Two major advantages are provided by using an endoscope. Primarily, one has the opportunity to look around a structure without disturbing or retracting that structure. In acoustic neurinomas, this advantage allows us to have a clear view into the internal auditory canal, providing an opportunity to detect even the smallest remnants of a neurinoma so that they can be removed under direct vision (Figs. 9.3–9.7). Improved illumination is a second major advantage to the use of an endoscope in microsurgery (Figs. 9.8–9.12). As the operative corridor deepens, light is reflected and absorbed by the intervening structures, reducing illumination in the depths of the exposure. The endoscope brings high-intensity illumination directly to the depths of the operative field. With the added illumination, the three-dimensional quality of the microscopic view is enhanced (Fig. 9.13–9.21).

Although each of the following cases of acoustic neurinomas could have been treated in the routine way described in the previous chapters, this combined microsurgical–endoscopic strategy proved to be valuable. In practiced hands, endoscope-assisted microsurgical procedures have proved to be safe. We have had no serious intraoperative or postoperative complications due to the adjunctive use of the endoscope in removing acoustic neurinomas.

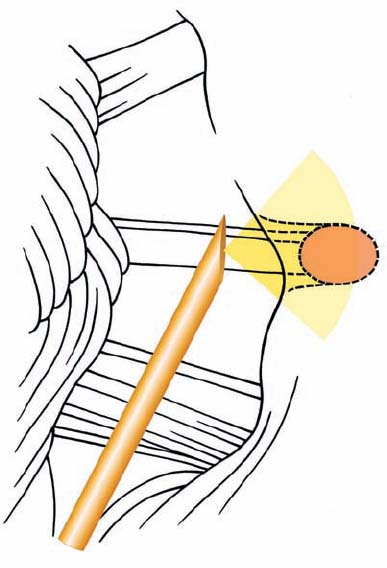

Fig. 9.1 The “fish-eye” effect. Note the increasing distortion as the edges of the image are approached. This is a completely different optical dimension from that provided by the surgical microscope.

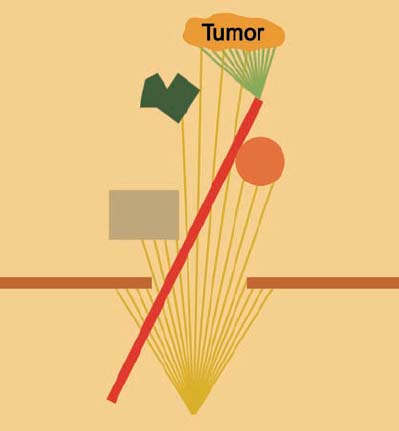

Fig. 9.2 The “scene” effect. Once structures have been passed, they can no longer be seen through the endoscope. When the endoscope is used alone, there is a risk of damaging structures that are out of view when it is being maneuvered.

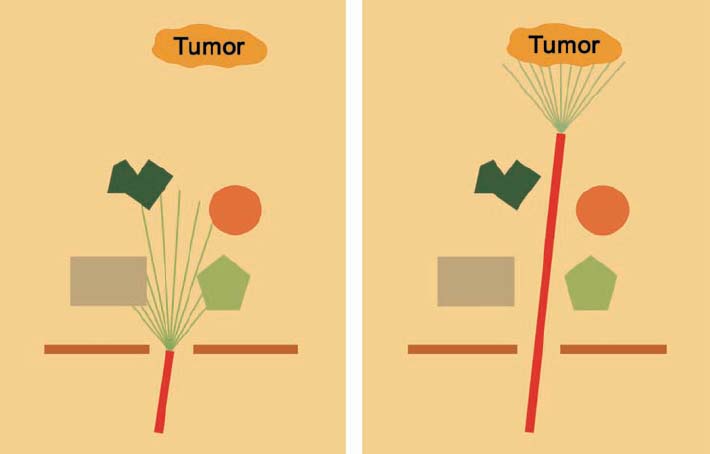

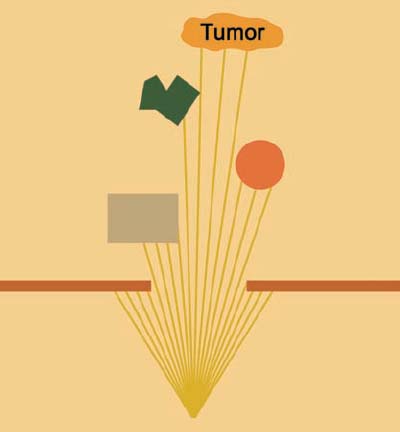

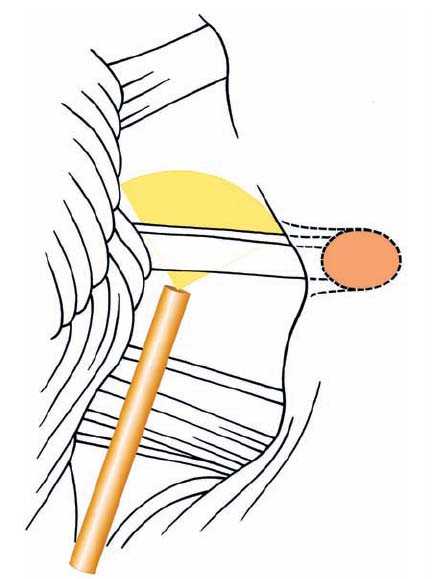

Fig. 9.3 The need for an additional optical instrument to see what is behind. When the microscopic optical field alone is moved, one is unable to look behind.

Fig. 9.4 Introducing an endoscope in addition to the microscopic view allows viewing behind—for example, in order to detect residual pathology without removing or even touching the obstruction.

Fig. 9.5 The strategy behind using an endoscope as an addition in the routine performance of a retromastoid approach. As seen here, one has an opportunity to look around a corner without the need to remove the posterior wall of the internal auditory canal.

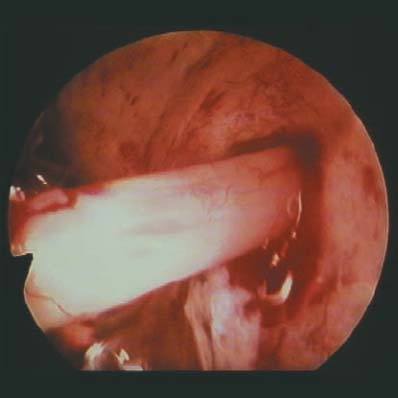

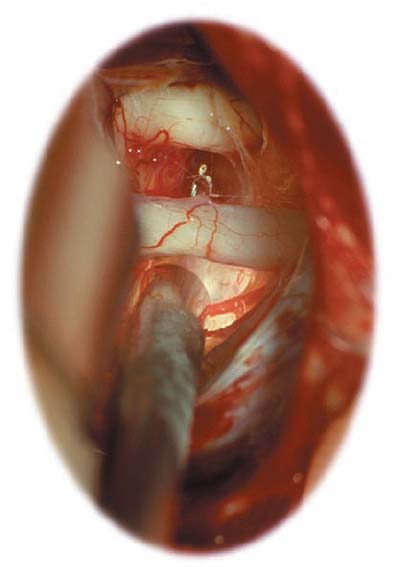

Fig. 9.6 The cerebellopontine angle viewed through the microscope, with introduction of an endoscope. The view through the microscope does not provide any optical information about the portions of the seventh and eighth cranial nerves as they enter the internal auditory canal, even when the angle of view is changed.

Fig. 9.7 The endoscopic view corresponding to Fig. 9.6. Visualization of the nerves entering the porus acusticus is possible through the endoscope.

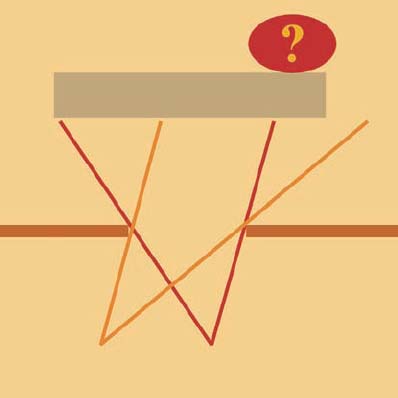

Fig. 9.8 The reflection and absorption of light from the microscope by structures located superficial to the tumor. This emphasizes the potential advantage of enhancing the illumination in the depths.

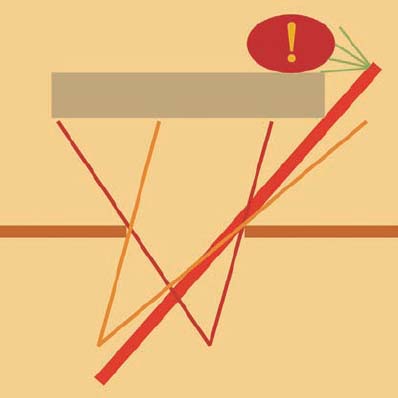

Fig. 9.9 Introducing an endoscope provides additional light to that of the microscope, enhancing illumination of the depths of the operative field.

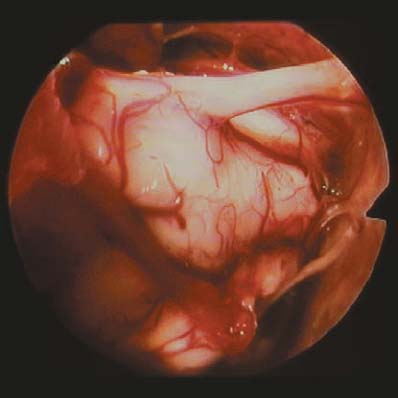

Fig. 9.10 The concept behind the use of an endoscope as an additional light source during a routine retromastoid approach. With the endoscope, it is possible to bring more light into the field without added retraction or other maneuvers.

Fig. 9.11 An intraoperative view, showing the additional illumination of structures in the depth, while endoscopic visualization is also provided.

Fig. 9.12 The endoscopic view seen from the position demonstrated in Fig. 9.11, showing additional endoscopic views of the trigeminal nerve, abducent nerve, and pons medial to the CN VII–VIII complex.

Fig. 9.13 A rigid endoscope, showing the cone of light using a 0° optical lens.

Fig. 9.14 Schematic drawing of the 0° lens instrument. Note that the optical axis is parallel to the axis of the endoscope.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree