Endovascular Treatment of Ischemic Stroke

Key Points

Techniques for endovascular revascularization of acute ischemic stroke are capable of achieving consistent success rates of over 90%.

Angiographic revascularization of ischemic stroke has become conflated with clinical efficacy. These are two entirely separate, and often unrelated, phenomena.

More than 80% of strokes worldwide are ischemic in origin and one in five of these affect the posterior circulation. Ischemic stroke is a heterogeneous diagnostic categorization involving a multitude of variables including age, cardiovascular health status, location and nature of the ischemic lesion, and the physiologic impact of the lesion in each individual patient. Identifying a single treatment modality that can improve outcomes in the setting of so many diverse circumstances has been and continues to be difficult.

Intravenous Thrombolysis

Intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke was described as far back as the 1950s (1). However, the first trials of intravenous thrombolytic agents administered within 6 hours of onset of ischemic stroke were not auspicious. Hemorrhage rates were unacceptably high with intravenous streptokinase, and a defined therapeutic impact was not evident with early trials of tPA probably due to the late timing of treatment (2,3,4). Finally, in 1995 with publication of the NINDS rt-PA study FDA approval was gained for use of intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) within 3 hours of onset of symptoms (5). A modest improvement in 90-day outcome was seen in patients treated with rt-PA compared with placebo. Patients treated with tPA were 30% more likely to have a good outcome at 90 days compared with patients treated with placebo. Symptomatic hemorrhage within 36 hours of administration of tPA was seen in 6.4% of tPA patients, while mortality rates in the tPA and placebo groups were similar at 17% and 21%, respectively. In 2008 the ECASS-III study additionally demonstrated a small but statistically significant effect of intravenous rt-PA in stroke patients during the 3- to 4.5-hour period since onset (6). Patients treated in this time window were 28% more likely to have a favorable outcome on the Modified Rankin Scale compared with placebo. Rates of symptomatic hemorrhage were higher with tPA (2.4% vs. 0.3%) and overall hemorrhage rates were substantially higher (27% vs. 17.6%) but without any difference in mortality rates (7.7% vs. 8.4%).

From trials of intravenous thrombolytic agents and other studies it was inferred that clinical improvement of the patient bore some relationship to the success of recanalization, although this correlation was difficult to define precisely. Independent of any thrombolytic agent, approximately 25% of all ischemic strokes will recanalize spontaneously within 24 hours and more than 50% will do so within 1 week (7,8,9). Administration of thrombolytic drugs improves acute recanalization rates to approximately 46% overall, and the chances of a good outcome at 3 months are increased by a factor of 4 or 5 in patients with immediate and sustained recanalization (7). Nevertheless, a good therapeutic outcome following intravenous thrombolytics is seen in substantially less than half of treated patients, and a sizeable proportion of patients deteriorate even in the absence of contraindications to administration of the drug (10).

In summary, intravenous thrombolytic therapy by itself helps at best only about a third of those ischemic stroke patients who are eligible for its strictly defined criteria, even when stretched to include presentation within 4.5 hours. Timing of administration is a factor, being twice as efficacious within the first 1.5 hours after onset of a stroke as it is when administered within 1.5 to 3 hours (6). Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage occurs in 1.7% to 8% of treated patients (5,6,11), and many patients are ineligible for this treatment due to late presentation or other reasons.

Intra-Arterial Treatment of Ischemic Stroke

Due to the shortcomings and limitations of intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke the drive to develop intra-arterial techniques of recanalization has been strong since the method was first described (12,13). Intra-arterial therapy offers several theoretical and actual advantages compared with bedside drug administration including

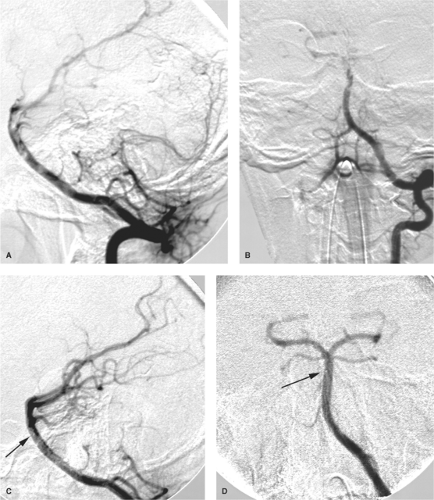

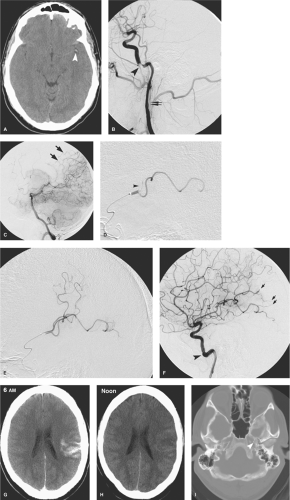

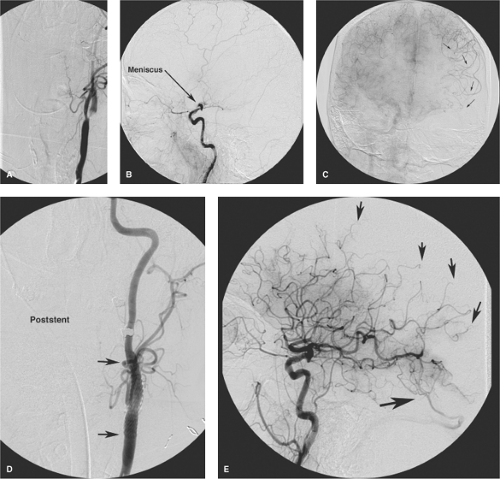

the capacity to deliver higher concentrations of local fibrinolytic agents into the clot itself and to monitor the state of vessel recanalization angiographically (Fig. 32-1). Furthermore, there is the potential to use several different mechanical techniques and devices sequentially until a winning solution is achieved (Figs. 32-2 and 32-3). However, it must be emphasized that the overarching focus on arterial recanalization in the literature dealing with intra-arterial therapy as a biomarker for successful therapy is potentially misleading. Given the correct circumstances endovascular recanalization of an ischemic lesion can be helpful, but recanalization

is not synonymous with reversal of ischemia or with the assurance of a good outcome.

the capacity to deliver higher concentrations of local fibrinolytic agents into the clot itself and to monitor the state of vessel recanalization angiographically (Fig. 32-1). Furthermore, there is the potential to use several different mechanical techniques and devices sequentially until a winning solution is achieved (Figs. 32-2 and 32-3). However, it must be emphasized that the overarching focus on arterial recanalization in the literature dealing with intra-arterial therapy as a biomarker for successful therapy is potentially misleading. Given the correct circumstances endovascular recanalization of an ischemic lesion can be helpful, but recanalization

is not synonymous with reversal of ischemia or with the assurance of a good outcome.

Three randomized trials of intra-arterial administration of thrombolytic drug for M1 or M2 occlusion have been published. The PROACT-II study identified a favorable outcome in 40% of patients treated with IA r-pro-UK versus 25% of placebo (heparin) patients, with a recanalization rate of 66% versus 18%, respectively (14). The Japanese MELT study also focused on MCA occlusions and found similar results (15). These studies were limited in scope and by the specific avoidance of mechanical disruption of the clot in the PROACT studies and only wire disruption in the MELT study, so the favorable outcome they describe is an indication of the power of even limited endovascular techniques in achieving recanalization. Since then, the expanding technologic capabilities of endovascular therapy have outraced and left behind the possibility of performing comprehensive randomized trials. Establishing vessel recanalization has become the de facto goal of treatment, with lesser attention paid to clinical outcome or complication rates, or so one might perceive from a review of the literature.

Endovascular intervention can achieve consistent rates of recanalization of 90% to 100% using a variety of snare, aspiration, balloon-angioplasty, and stent devices, particularly when multiple modalities are employed (16,17,18,19,20). These rates represent a considerable improvement over the recanalization rates seen with intravenous therapy alone (30% to 46%) and rates seen with exclusive use of intra-arterial thrombolytics or one mechanical device alone (60% to 70%) (21,22,23). Intra-arterial treatment of ischemic stroke can be performed on pediatric patients (24) and octogenarians sometimes with margins of safety and angiographic success comparable to those in other age groups, sometimes not (25,26), with only an occasional question being raised as to whether this is sustainable from a medical resource point of view, cost efficacy, or clinical outcome. The phenomenon of “futile recanalization” is well recognized and commonplace, that is, the acknowledgment that reopening an ischemic vessel really does not accomplish anything positive for the patient and may do a great deal of economic and medical harm. It is not uncommon for high double-digit published rates of futile recanalization (90%) or triple-digit rates of successful stent deployment to be juxtaposed with extremely modest rates of clinical improvement (27,28). The illusory success of achieving recanalization at such a high rate compounded with the phenomenon that aggressive stroke therapy is being touted as a showcase or marketing tool for many medical institutions means that the likelihood of rationalization or triage of stroke patients away from intra-arterial therapy seems even more improbable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree