Epidemiology in Developing Countries

Nadir E. Bharucha

Arturo Carpio

Amadou Gallo Diop

Introduction

The term developing is taken usually to mean economically developing from poverty toward affluence. Geographically, most such countries are found in Asia, Africa, and Central and South America. However, several countries or parts of countries in these areas are considered quite affluent and correspondingly, some parts of developed countries are economically developing, namely, Eastern Europe.

Although there are no inherent differences between developing and developed countries regarding the biologic and clinical aspects of epilepsy, differences are found in incidence, etiology, social and cultural factors, and systems of health care delivery and treatment.

Developing countries often do not have an organized health care system. Record keeping is generally poor and research minimal. Neuroimaging and drug monitoring facilities may be available, but patients are often too poor to afford what can be obtained. Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) also may not be available and for various reasons may not be taken. As a result, a large proportion of people with epilepsy do not get treatment. In addition, little accurate scientific data have come from developing countries. In view of this paucity of information, it is easy to assume that the experience of developed countries in treating epilepsy can be applied without modification to developing countries. The purpose of this chapter is to highlight differences in the epidemiology of epilepsy between developed and developing countries, so that such experience can be meaningfully and profitably applied for the benefit of patients.

Incidence and Prevalence

The evaluation of published vital statistics in epilepsy is often complicated by methodologic problems that have not been fully addressed.91,93 Problems that bedevil studies of incidence and prevalence in developing countries include diagnosis, case ascertainment, and definitions of seizures and epilepsy. The early pioneer studies particularly exhibited these weaknesses, although they did provide approximate statistics upon which later investigations could build.

Methodology

Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis is essential, both at presentation and during treatment. It is mainly clinical, depending on history and examination. Electroencephalography (EEG) contributes to, but does not always confirm, the diagnosis. Accuracy of diagnosis is vitiated by lack of an eyewitness account. A therapeutic trial of antiepileptic drugs is never warranted. Even in developed countries in patients referred with a diagnosis of refractory epilepsy, the rate of misdiagnosis may be as high as 26.1%.103 The most common misdiagnoses are psychogenic, nonepileptic seizures and syncope. In two Indian population-based studies, syncope was frequent in one and psychogenic seizures in another.9,52 Such information is invaluable to a clinician working in India.

Case Ascertainment

In developing countries, concealment of epilepsy for social reasons is common. People also may be genuinely unaware of seizures that present differently from tonic–clonic seizures. Accurate case ascertainment requires a community-based door-to-door survey using a locally validated questionnaire in order to screen the population, with the informed consent of the individuals concerned, the family, and community leaders. If key informants and local medical workers are used, including traditional healers, then case ascertainment will be much better. The capture-recapture method also uses information from different sources to obtain a prevalence ratio that is higher than that obtained from using a door-to-door survey alone.27 Another way of enhancing the yield of a door-to-door survey is to examine a random sample of those people who in the door-to-door survey had been found not to have epilepsy. This enables calculation of the rate of false negatives.86

Definition of Seizures and Epilepsy

In 1993, the International Commission of Epidemiology and Prognosis of the International League against Epilepsy (ILAE) published guidelines for epidemiologic studies.45 These guidelines give definitions of seizures and epilepsy, a classification, risk factors, and recommended measurement indices. These are particularly useful for field studies in developing countries, where facilities for investigation are unavailable. Unfortunately, these guidelines are not always followed.

It should be remembered that acute symptomatic seizures, although not considered epilepsy, are common. Such patients do not need long-term treatment for seizures, but they do need treatment for the acute seizure and for the underlying condition, which, in developing countries, most commonly is neurocysticercosis.75 In addition, the terms idiopathic and cryptogenic epilepsy should not be confused. In a developing country without investigations, making the distinction is not always possible in a field study. Studies should mention the amount of active epilepsy (i.e., those who have had at least one seizure within the past 5 years). These people are important from the point of view of public health.

Table 1 Incidence Studies of Epilepsy in Developing Countries | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 2 Incidence of Epilepsy in the Americas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Incidence is defined as the rate of occurrence of new cases in a specified population per unit time, usually 1 year. The numerator is the number of new cases. The denominator is the number of persons at risk, although usually the total population is used. Prevalence is defined as the proportion of a specified population with the disease at a specified time. Point prevalence is this proportion on a particular day.

Both incidence and prevalence studies are useful for health service providers, especially in developing countries with few neurologists and 80% of the burden of epilepsy. Incidence studies give clues to risk factors and information about prognosis, but there are few studies from developing countries because they are difficult to carry out.

Incidence

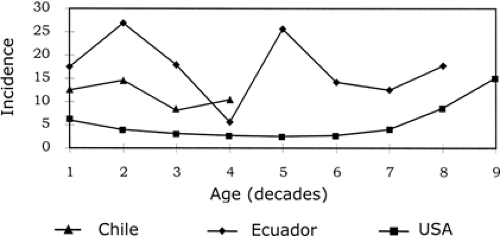

In developed countries, the age-adjusted incidence of epilepsy, defined as recurrent unprovoked seizures, ranges from 28.9 to 53.1 per 100,000 person-years, with most studies falling toward the higher end of this range.42 If single unprovoked seizures are included, higher figures, up to 70 per 100,000 person-years, are obtained. The few available studies in developing countries, none of which is prospective (Table 1), give a range from 35 to 190 per 100,000 person-years. The Ecuadorian study, in which the incidence range was 122 to 190 per 100,000 person-years, includes single seizures and acute symptomatic seizures.86 The incidence of epilepsy in five sub-Saharan African studies ranges from 63 to 158 per 100,000 person-years.87 Comparisons of rates are valid only when age-adjusted to the same population. This has been done for the Americas22 and is given in Table 2. The higher incidence in developing countries may be a consequence of the fact that populations in the developing world are younger and have poorer medical facilities, poorer general health, and a lower standard of living. Specifically, there are more infections of the central nervous system (CNS), especially with cysticercosis, tuberculosis (TB), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Perinatal morbidity, head injuries, and consanguinity are also more common. The relative importance of these factors is unknown.

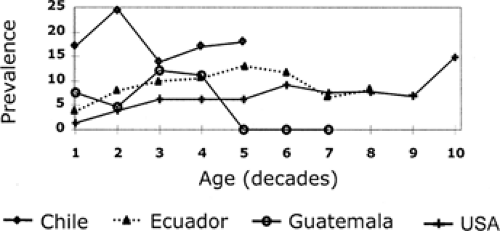

The graph of age-specific incidence of epilepsy in developed countries is a U-shaped curve, with the highest incidences in those <1 year old and >60 years old. It rises sharply after age 60. In developing countries, the peak incidence occurs in young and middle-aged adults10,56 (Fig. 1). The different age-specific incidence rates in developed and developing countries have two implications. One is that the risk factors may differ. In developing countries infections and parasitic diseases are endemic. The second is the difficulty of comparing studies from countries with differing stages of development and age distribution of the population without age adjustment to a common population as the denominator.

The age-specific incidence of epilepsy in developed countries has been changing over time. There has been a decrease in childhood epilepsy due to better perinatal care, as well as an increase in epilepsy among the elderly because of rising cerebrovascular disease. Such data are not available for developing countries, but that from developed countries suggests the possibility of reducing the present burden by improving obstetric and perinatal care and diminishing future burden by early attention to prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Incidence throughout the world is slightly higher in males than females. The Ecuadorian study found a preponderance of females. Many studies have found no difference. When found a difference, it was slight.

Seizure Type

In general, partial seizures are more common in developed countries than other seizure types, accounting for just over 50%. In developing countries, where symptomatic epilepsy is more common, one would expect partial seizures to predominate. However, in differing circumstances, generalized tonic–clonic seizures tend to be more commonly noted for the following reasons, none of which seems to apply to all situations:

The partial onset of a seizure that rapidly generalizes will be missed by the patient or the field worker.

Untreated partial seizures may become generalized more rapidly.

A questionnaire may not be designed to pick up anything apart from generalized tonic–clonic seizures.

There is a lack of the EEG to pick up a focal onset.

There are no population-based incidence studies of epilepsy syndromes from developing countries.

FIGURE 1. Age-specific incidence of epilepsy in the Americas. (From Carpio A. Perfil de la epilepsia en el Ecuador. Revista Ecuatoriana de Neurologia. 2001;10:20–26.) |

Table 3 Prevalence of Active Epilepsy in the Americas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prevalence

There have been many more studies of the prevalence of epilepsy than of incidence because they are much more easily carried out. Although methodologic differences among these

studies make comparisons difficult, it seems clear that, unlike incidence, the prevalence of active epilepsy remains within the range of 4 to 10 per 1,000 population throughout the world.46 Higher prevalences have been reported from sub-Saharan African countries (e.g., 35.1 per 1,000 in Benin using the capture-recapture method27 and the prevalence of 49 per 1,000 in Grand Bassa county in Liberia36). A rate of 20 per 1,000 was found among the Wapogoro in Tanzania.50 In South and Central America, a rate of 57 per 1,000 has been found among the Guaymi Indians of Panama.34 In areas with a high prevalence, there is often a strong family history of both epilepsy and consanguinity, possibly as a result of social stigma forcing intermarriage. A large number of studies in India and China suggest a prevalence of active epilepsy of between 4 and 6 per 1,000, similar to that in developed countries.9,54,104,111

studies make comparisons difficult, it seems clear that, unlike incidence, the prevalence of active epilepsy remains within the range of 4 to 10 per 1,000 population throughout the world.46 Higher prevalences have been reported from sub-Saharan African countries (e.g., 35.1 per 1,000 in Benin using the capture-recapture method27 and the prevalence of 49 per 1,000 in Grand Bassa county in Liberia36). A rate of 20 per 1,000 was found among the Wapogoro in Tanzania.50 In South and Central America, a rate of 57 per 1,000 has been found among the Guaymi Indians of Panama.34 In areas with a high prevalence, there is often a strong family history of both epilepsy and consanguinity, possibly as a result of social stigma forcing intermarriage. A large number of studies in India and China suggest a prevalence of active epilepsy of between 4 and 6 per 1,000, similar to that in developed countries.9,54,104,111

As with incidence, rates that are age-adjusted to a common denominator for the Americas allow more meaningful comparisons (Table 3).22

Age-specific Prevalence

Sex

Seizure Type

As is the case with incidence studies and for the same reasons, generalized seizures are more common than partial seizures in developing countries. There are exceptions. In the Ecuadorian study, 49% had partial seizures, which may reflect the input of the specialist medical team. The Parsis had 54.5% partial seizures, a figure possibly resulting from the medical input and the community’s higher level of education. When EEG is used in addition, the proportion of partial seizures increases. In a Ugandan study it rose from 24% to 42%51 and in a Bolivian study from 34% to 53%.78

Socioeconomic Factors

Studies in developed countries have suggested that socioeconomic deprivation increases the risk of epilepsy.33,44,60,73 Studies in Ecuador, Pakistan, and Turkey showed the prevalence of epilepsy to be higher in rural areas, but the reverse was shown in the meta-analysis of the Indian studies.4,5,86,104 In India, poverty is greater in rural areas where it is more difficult to conceal epilepsy. The whole relationship of socioeconomic factors to epilepsy needs further exploration.

Incidence-prevalence “Gap”

The term incidence-prevalence gap refers to the higher incidence of epilepsy in developing countries than in developed countries, whereas prevalence values are similar throughout the world.11,16,57,70,78,86,89 Possible explanations are differences in methodology, namely, inclusion of acute symptomatic seizures as incidence cases in developing countries; the higher mortality rate in developing countries10,15; and higher rates of remission, which would imply a more benign prognosis. There are no answers yet to these speculations, nor will there be until there are

well-conducted incidence studies and population-based outcome studies from developing countries. Certainly, there need be no further prevalence studies, unless they are designed to look at specific epilepsy syndromes or health status.

well-conducted incidence studies and population-based outcome studies from developing countries. Certainly, there need be no further prevalence studies, unless they are designed to look at specific epilepsy syndromes or health status.

Prognosis

The prognosis of epilepsy is defined by Hauser and Hesdorffer39 as the risk of recurrence following a first seizure or more seizures; the probability of remission, both spontaneous and with treatment; the risk of relapse following drug withdrawal; and the mortality of epilepsy. It has been suggested that in these countries, the prognosis of epilepsy is different, but few studies of natural history allow comparisons.1,12,16 Methodologic shortcomings have contributed to the uncertainties.39,90

Recurrence after a First Unprovoked Seizure

In developed countries, prognosis for full seizure control is very good. More than 70% of patients achieve long-term remission, most within 5 years of diagnosis.40,61,101 In developing countries, after a first unprovoked seizure, the risk of recurrence is 33% to 37%, similar to that from developed countries.18,26,53,94 Studies from developing countries show that patients with epilepsy secondary to underlying structural causes and with an abnormal EEG have the worst prognosis.18,53,94 The type of seizure and drug treatment used seem not to affect prognosis. Developing countries have produced no published studies of the prognosis of epileptic syndromes.

Recurrence in Newly Diagnosed Epilepsy (or Probability of Remission)

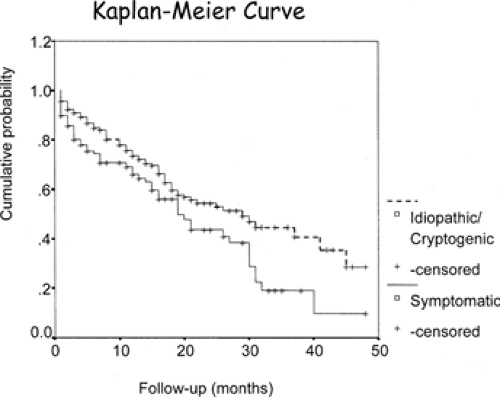

In developed countries, most studies of seizure prognosis or epilepsy prognosis in adults23,40,61,62,96 and children3,99,101 have examined the risk of recurrence following a first unprovoked seizure, but according to ILAE definitions, a single unprovoked seizure does not constitute epilepsy. Very few studies have reported the risk of recurrence after a second seizure.41,100 Hauser et al.,41 in the United States, reported that the risk of a third unprovoked seizure was 73% after 4 years of follow-up. The study by Shinnar and Pellock,100 in the United States, showed that the cumulative risk of a third seizure was 71% at 5 years. Carpio et al.,18 in Ecuador, found that in 340 newly diagnosed epilepsy patients with one recurrent unprovoked seizure, the risk of a third unprovoked seizure was 79% after 4 years of follow-up. Etiology was an independent predictor of recurrence. Patients with idiopathic cryptogenic epilepsy had less risk of recurrence than patients with symptomatic epilepsy (38% vs. 52%, p <0.05). FIGURE 3 shows the probability of seizure recurrence. Multivariate analysis showed no significant differences in recurrence risk due to sex, age, family history of epilepsy, EEG results, or the type of seizure.

Prognosis for Seizure Recurrence in Patients with Neurocysticercosis

Very few studies estimate the prognosis of acute symptomatic seizures. Seizures due to neurocysticercosis (NC) demonstrate prognosis well. In a prospective, cohort study in Ecuador, Carpio and Hauser19 found that 40% of patients had a recurrence. Multivariate analysis showed that the only predictor of recurrence was a change in appearance on the computed tomography (CT) scan. Twenty-two percent of patients in whom cysts disappeared had no further seizures, but 56% of those with persistent cysts had a recurrence (p <0.05). The authors’ conclusion that seizure recurrence is high following a first acute symptomatic seizure due to NC, therefore, seems related to persistence of active brain lesions. However, when the NC lesion clears up, the recurrence risk is low and in keeping with the risk following other brain insults leading to a static encephalopathy. There was no correlation between treatment with antihelminthic agents and seizure recurrence.

Spontaneous Remission and Effect of Treatment on Prognosis

Some patients spontaneously enter remission.57 In a retrospective survey of 460 previously untreated patients attending newly established epilepsy clinics in Malawi, Watts112 indirectly demonstrated spontaneous remission. The study found that as the duration of epilepsy increased, the number of patients with active epilepsy decreased. Thus, remission without therapy is common. This finding is substantiated by an Ecuadoran survey in which 28% of all identified cases entered remission without treatment84 and by Mani et al.66 in a rural community in south India, from which he reported a remission rate of 50% of untreated patients.

Antiepileptic drug trials30,31,85 reported from Nakuru, Kenya, and Ecuador show a generally excellent response to standard therapy. These studies also show that in patients who had not previously received antiepileptic drug (AED)

treatment, neither the duration of the disease nor the number of seizures before treatment are predictors of outcome. This was corroborated by a more recent study from Yelandur, India.64 Therefore, failing to treat seizures at the earliest possible opportunity does not increase the likelihood of chronicity and agrees with findings from developed countries that for most patients, the chance of remission is not improved by early treatment.68,76 Treatment reduces the rate of recurrence of seizures but does not affect the natural history of epilepsy. There is some conflicting evidence from a hospital-based study in Glasgow, which showed that those who had had 20 or more seizures before starting treatment were more likely to have refractory epilepsy.55 The authors concluded that there was some underlying abnormality of the brain, which rendered the epilepsy refractory from its inception (i.e., frequent seizures could be an indicator of refractoriness rather than cause). The study from Yelandur in India also suggested that those with a lifetime total of more than 30 seizures had less chance of entering remission. More outcome studies are needed from developing countries with populations whose epilepsy is still largely untreated.

treatment, neither the duration of the disease nor the number of seizures before treatment are predictors of outcome. This was corroborated by a more recent study from Yelandur, India.64 Therefore, failing to treat seizures at the earliest possible opportunity does not increase the likelihood of chronicity and agrees with findings from developed countries that for most patients, the chance of remission is not improved by early treatment.68,76 Treatment reduces the rate of recurrence of seizures but does not affect the natural history of epilepsy. There is some conflicting evidence from a hospital-based study in Glasgow, which showed that those who had had 20 or more seizures before starting treatment were more likely to have refractory epilepsy.55 The authors concluded that there was some underlying abnormality of the brain, which rendered the epilepsy refractory from its inception (i.e., frequent seizures could be an indicator of refractoriness rather than cause). The study from Yelandur in India also suggested that those with a lifetime total of more than 30 seizures had less chance of entering remission. More outcome studies are needed from developing countries with populations whose epilepsy is still largely untreated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree