and Héctor H. García3, 4

(1)

School of Medicine, Universidad Espíritu Santo, Santo, Ecuador

(2)

Department of Neurological Sciences, Hospital-Clinica Kennedy, Guayaquil, Ecuador

(3)

Cysticercosis Unit, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Neurológicas, Lima, Peru

(4)

School of Sciences, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru

Abstract

Non-endemic areas for cysticercosis could be defined as those places where the life cycle of Taenia solium cannot be fully completed, as one or more of the several interrelated steps needed for its completion are not present (Del Brutto and García 2012). Those steps include the following: (1) the presence of Taenia carriers harboring the adult tapeworm in the intestine, (2) the practice of open-air fecalism or improper disposal of human feces, (3) the allowance of free-roaming pigs having access to human feces, and (4) the consumption of undercooked pork. When these four steps are associated with illiteracy, poverty, poor sanitization, and a warm climate, the prevalence of human taeniasis as well as that of human and porcine cysticercosis may attain endemic consequences and may represent a major public health problem (García et al. 2007). As noted in the preceding chapter, this is what happens in most of the developing world.

Non-endemic areas for cysticercosis could be defined as those places where the life cycle of Taenia solium cannot be fully completed, as one or more of the several interrelated steps needed for its completion are not present (Del Brutto and García 2012). Those steps include the following: (1) the presence of Taenia carriers harboring the adult tapeworm in the intestine, (2) the practice of open-air fecalism or improper disposal of human feces, (3) the allowance of free-roaming pigs having access to human feces, and (4) the consumption of undercooked pork. When these four steps are associated with illiteracy, poverty, poor sanitization, and a warm climate, the prevalence of human taeniasis as well as that of human and porcine cysticercosis may attain endemic consequences and may represent a major public health problem (García et al. 2007). As noted in the preceding chapter, this is what happens in most of the developing world.

In contrast, industrialized nations of North America, Western Europe, and Oceania have developed, through the past decades, secure systems of sewage disposal and adequate mechanisms of husbandry, precluding pigs to be in contact with human feces, thus avoiding the life cycle of Taenia solium to be completed. There are also some regions—developed or not—where the life cycle of the tapeworm cannot be completed, as their religious beliefs prohibit the consumption of pork; these include Israel and Muslim countries of the Arab world.

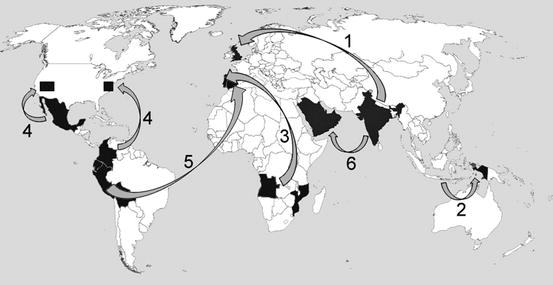

Traditionally considered non-endemic regions have been faced, during the past decades, with the massive immigration of people coming from cysticercosis-endemic areas that, together with increased overseas travelling and refugee movements, progressively increased the number of patients with neurocysticercosis in these regions. As known, the first non-endemic country experiencing such increased prevalence was the UK after the massive return of soldiers on duty from the Indian subcontinent (MacArthur 1934). This has been followed by a number of bouts of human cysticercosis in other non-endemic regions, related to either mass movement of people or infected swine from endemic to non-endemic areas (Fig. 5.1).

Fig. 5.1

World map showing major outbreaks of human cysticercosis related to mass movement of people or infected swine from endemic to non-endemic areas. (1) Return of British soldiers from India to England; (2) gift of infected swine from Bali to Irian Jaya; (3) mass return of Portuguese living in African colonies after liberty wars in Angola and Mozambique; (4) migratory movements of people from Mexico and South America to the USA (mainly to the Southwestern USA and the New York city area); (5) mass migration of people from Ecuador, Perú and Bolivia to Spain; (6) migration of people from India to countries of the Arabian Peninsula (Reproduced with permission from: Del Brutto (2012d))

While initially almost all cases of human cysticercosis diagnosed in non-endemic regions occurred in immigrants or in people repatriated from disease-endemic areas, the problem has been complicated by the increasing occurrence of autochthonous cases, i.e., patients born in non-endemic regions who have never been abroad (García 2012). This created confusion among physicians and health authorities who, mostly unaware on the mechanisms of disease transmission, could not found an explanation to this. It was later understood that, in the same way as people with cysticercosis migrate from disease-endemic to non-endemic areas, asymptomatic Taenia carriers also migrate, and they represent the source of infection to local people, thus increasing and favoring the spread of cysticercosis in non-endemic countries without the need of infected pigs (Schantz et al. 1992). Despite this evidence, little has been done to detect the Taenia carrier among close contacts of neurocysticercosis patients living in non-endemic regions. Moreover, the illegal status of many of these persons complicates even more the access to household contacts of neurocysticercosis patients in the search of Taenia carriers.

Nowadays, there is almost no country, considered as non-endemic, where at least a few human cases of cysticercosis have been reported. In general terms, it can be stated that more than 80 % of these cases occur in immigrants from disease-endemic areas. However, on the basis of disease expression of neurocysticercosis in some of these immigrants, it is possible that they were not infected back in their country of origin (before migration), but after they arrived to the non-endemic area (Del Brutto et al. 2012a, b).

5.1 The United States

Human cysticercosis was considered exceedingly rare in the USA, with only 42 cases being reported since 1857–1954 (Campagna et al. 1954). During the following years and up to the late 1970s, a number of case reports and small series of patients also called the attention to the occurrence of this parasitic disease in the USA, suggesting that its prevalence was on the rise (Bentson et al. 1977; Carmalt et al. 1975; Cohen 1962; DeFeo et al. 1975; White et al. 1957). Together with the mass immigration of people from Mexico and other Latin American countries, the first bouts of human cysticercosis were noticed in the Southwestern USA—mainly in the states of California and Texas—where more than 500 patients were recognized during the 1980s, most of whom were of Mexican origin (Earnest et al. 1987; Grisolia and Wiederholt 1982; Loo and Braude 1982; McCormick 1985; McCormick et al. 1982; Mitchell and Snodgrass 1985; Richards et al. 1985). A literature review of case series of neurocysticercosis patients diagnosed in the USA from 1980 to 2004 found almost 1,500 patients (Wallin and Kurtzke 2004), a number that increased to more than 5,000 when more recent publications were included (Croker et al. 2010, 2012; O’Neal et al. 2011; Serpa et al. 2011). However, these alarming numbers are clearly an underestimate since neurocysticercosis is not a reportable disease in most states (Serpa and White 2012). Assessing the actual burden of neurocysticercosis in the USA is complicated. Conservative analysis estimates annual incidence rates ranging from 1.5 to 5.8 cases per 100,000 in Hispanics and from 0.02 to 0.5 cases per 100,000 in non-Hispanic whites (O’Neal et al. 2011; Sorvillo et al. 1992; Townes et al. 2004).

As noted, most cases of neurocysticercosis in the USA occur among immigrants from disease-endemic countries. However, up to 7 % of cases in some series have been autochthonous, reflecting the occurrence of locally acquired disease (Sorvillo et al. 1992). A literature review showed 78 well-documented cases of neurocysticercosis acquired in the USA up to the year 2005; in 21 % of these patients, a close contact infected with the adult Taenia solium was found (Sorvillo et al. 2011). The most precisely described example of this form of acquisition of human disease in the USA was reported in the Orthodox Jewish community of New York City, where some of their members (child and adults) developed neurocysticercosis as the result of infection from domestic employees recently emigrated from Latin America who were found to be Taenia solium carriers, infecting people for whom they worked through non-hygienic handling of food (Schantz et al. 1992).

While most patients with neurocysticercosis diagnosed in the USA presented with seizures and parenchymal brain granulomas, thus having a benign prognosis, some developed severe forms of the disease such as giant subarachnoid cysts or hydrocephalus (Kelesidis and Tsiodras 2011) and others have even died as the result of the infection (Sorvillo et al. 2007).

5.2 Canada

Swine cysticercosis has been recognized in Canada since the nineteenth century (Cameron 1934). However, according to Canadian health authorities, there were no reported cases of human cysticercosis in the country up to 1956 (White et al. 1957). During the 1970s, isolated case reports called the attention to the occurrence of this condition among immigrants to Canada (Ali-Khan et al. 1979; Scholten et al. 1976), and by 1986, the first series of eight patients with neurocysticercosis was reported from Montreal; all of them were immigrants from disease-endemic areas (Leblanc et al. 1986). Soon thereafter, Sheth et al. (1998) reported 29 patients with neurocysticercosis evaluated at Toronto over 6 years; however, no details were given on the citizenship status of these patients. More recently, several reports have confirmed the sporadic occurrence of this parasitic disease in Canada, always in immigrants from endemic areas (Boulos et al. 2010; Brophy and Keystone 2006; Burneo and McLachlan 2005; Burneo et al. 2009; Hajek and Keystone 2009).

A recent review of the literature of human cysticercosis in Canada (Del Brutto 2012a) identified a total of 55 patients with neurocysticercosis, most of who were diagnosed over the past two decades. Patients were mainly concentrated in Ontario and Quebec. Information on the citizenship status was available in only 28 of these patients. Twenty-seven of them were immigrants from disease-endemic areas, and the remaining case was a Canadian citizen with history of traveling abroad. Information on the time elapsed between immigration and symptomatic disease varied widely from a few months to more than 30 years, raising the question of whether some of these immigrants could have been infected while already living in Canada. While literature information is rather incomplete, it could be inferred that most of these patients presented with seizures related to the occurrence of parenchymal brain cysts or granulomas. Stool examinations were performed in just a few patients, and some of them were positive for Taenia eggs. In no case were household contacts investigated for taeniasis. This recent review let it clear that human cysticercosis is an emerging problem in Canada. However, no actions have yet been taken to reduce its impact burden or to prevent further spread of the disease (Burneo 2012).

5.3 Western European Countries

While human cysticercosis has been linked to Western Europe for centuries, the disease became neglected during the past decades just because it was considered rare (Overbosch et al. 2002). A re-emergency of the disease is currently happening in some of these countries due to the massive immigration of people from Africa and South America that took place during the past two decades. For example, neurocysticercosis in Spain remained endemic during the twentieth century up to the 1980s, where its prevalence was reduced to 4.3 % per 100,000 inhabitants, with cases confined to rural areas (García-Albea 1991). Together with the growing number of immigrants, more than 100 “urban” cases have been recognized during the past decade, mostly among South American immigrants (Giménez-Roldán et al. 2003; Más-Sesé et al. 2008; Ramos et al. 2011; Ruiz et al. 2011). Likewise, most of the cases reported from Portugal were temporarily related to the massive return of Portuguese citizens from their African colonies after their independence (Almeida-Pinto et al. 1988; Monteiro 1993; Monteiro et al. 1986, 1992, 1993, 1995; Morgado et al. 1994).

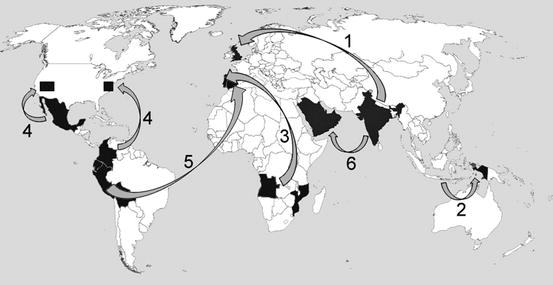

A recent literature search identified 779 patients with neurocysticercosis diagnosed in Western Europe from 1970 to 2011 (Del Brutto 2012b). Countries with more reported patients were Portugal (n = 384), Spain (n = 228), and France (n = 80), followed by the UK, Italy, and Germany; in the remaining countries, there was either no data or the reported number of patients was five or less (Fig. 5.2). Community-based studies attempting to determine the prevalence of human cysticercosis is European villages have been scarce. In Northeastern Portugal, 5 % of the inhabitants had antibodies against cysticercus antigens in serum (Meneses-Monteiro 1995). In another study, 29 patients with neurocysticercosis were found over a 10-year period in Southeastern France (Rousseau et al. 1999). Some information also exists on the prevalence of neurocysticercosis among neurologic patients attending specialized centers in Portugal and Spain. In the former, neurocysticercosis accounted from 0.1 to 0.7 % of patients evaluated with CT at two large hospitals in Porto and Lisbon during the 1980s and 1990s (Monteiro et al. 1992; Morgado et al. 1994). In Spain, a mean of two new patients with neurocysticercosis per year has been evaluated during the past decades at large hospitals in Vigo and Madrid (Esquivel et al. 2005; Fandiño et al. 1989; García-Albea 1989).

Fig. 5.2

Map of Western Europe showing countries with the number of reported cases of neurocysticercosis from 1970 to 2011

Information on the citizenship status of neurocysticercosis patients diagnosed in Western European countries is incomplete. Nevertheless, it could be extracted from the literature that most are immigrants from disease-endemic countries. In such cases, symptomatic disease has occurred after a mean of 5 years of being living in Europe. Most patients came from South America and Africa, the former being most often diagnosed in Spain and the latter in France and Portugal. Immigrants from the Indian subcontinent and other regions of Asia were more often diagnosed in the UK (Kennedy and Schon 1991; Wadley et al. 2000). With the exception of some international travelers, most European citizens with neurocysticercosis acquired the infection in the Western European territory as the result of close contact with Taenia carrier immigrants, and it is likely that the same happened with some of the immigrants with neurocysticercosis, particularly those who developed the disease 20 or more years after being living in Europe (Del Brutto and García 2012; Del Brutto et al. 2012a, b).

5.4 Countries of the Arab World

Due to religious laws prohibiting swine breeding and consumption of pork, human cysticercosis has been considered inexistent in Muslin countries of the Arab world with the exception of sporadic cases seen in immigrants from India during the last two decades of the twentieth century (Chandy et al. 1989). More recently, a number of case series suggested that the prevalence of neurocysticercosis in the region is on the rise. Indeed, a literature search from the year 2000 to 2011 allowed the identification of 39 patients with neurocysticercosis (Del Brutto 2013). Most of these patients were from Kuwait, although some came from Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Patients were most often young women, and most had a benign clinical course, since the most common pattern of disease expression of neurocysticercosis in Arabian is a single parenchymal brain cysticercal granuloma (Abdulla et al. 2006; Al Shahrani et al. 2003; Al-Khuwaitir et al. 2005; Hamed and El-Metaal 2007; Hira et al. 2004; Hussein et al. 2003; Khan et al. 2011).

Most patients reported from the Arab world were autochthonous, and occurred in the context of wealthy families employing babysitters and housekeepers from disease-endemic areas. Indeed, familiar cases of neurocysticercosis were recorded in some cases. Most important, stool examinations in household contacts of some of these patients allowed the identification of Taenia carriers.

5.5 Australia and New Zealand

Taeniasis and cysticercosis have always been considered rare in Oceania. However, a number of recent reports suggest that neurocysticercosis is increasingly recognized in this Continent. A total of 39 neurocysticercosis patients have been reported from Australia, 33 of whom were published in the past two decades. This does not seem to be the case of New Zealand, as only two patients have been described in that country (Pybus and Heron 2012; Wickremesekera et al. 1996).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree