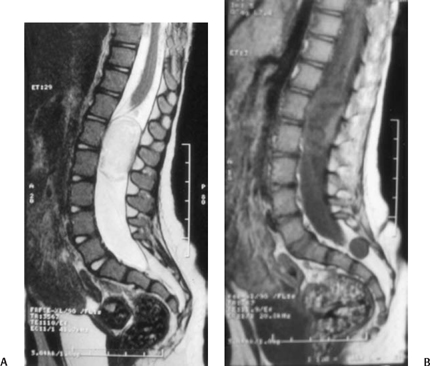

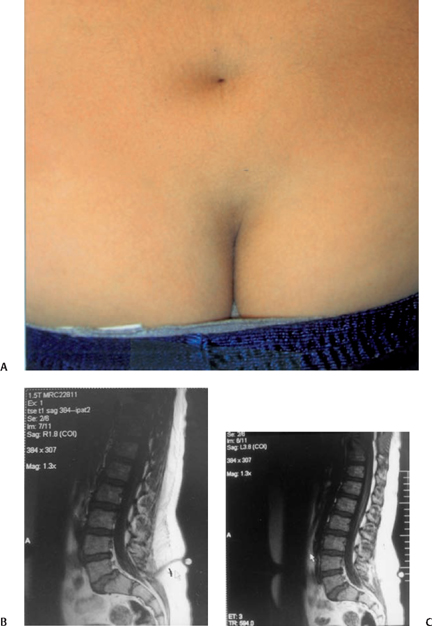

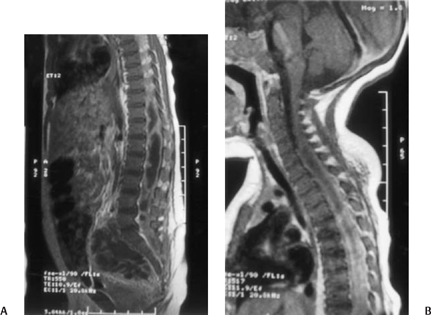

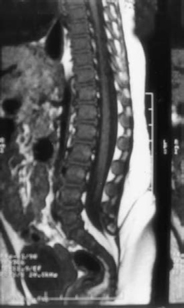

14 Epidermoid and Dermoid Tumors Associated with Tethered Cord Syndrome David S. Knierim, Daniel J. Won, and Shokei Yamada Epidermoid and dermoid tumors are usually thought of as developmental tumors. They may also be inclusions from previous surgery when elements of dermis or epidermis are retained with the neural placode at the time of myelomeningocele repair in spina bifida.1 On rare occasions, these benign tumors can be caused by skin fragments that were implanted in the spine as a result of invasive procedure such as lumbar puncture.2,3 They usually occur at or near the midline and can be associated with tubular dermal sinus tracts. They can be encountered in the nasofrontal region, the occipital region, and along the spine. The dermal sinus tracts that often connect to dural reflections or stalks are of greater potential for development of symptoms. Further tract communications with the central nervous system (CNS) are the potential source of three major complications: (1) CNS infection through the tract as a conduit for bacteria, (2) CNS compression by mass effect, and (3) tethered cord syndrome related to inelastic structures that anchor the caudal spinal cord, such as sinus tracts themselves, dural stalks, and inclusion cysts. The incidence of dermal sinus tract is ∼ 1 in 2500 live births.4–6 Dermal sinus tracts have been reported all along the midline neuraxis from the nasion and occiput down to the lumbar and sacral region. The majority occur in the lumbar and lumbosacral region.7,8 Often there is an associated cutaneous lesion overlying the midline anomaly or dermoid tumor, such as a cutaneous angioma, hypertrichosis, or a dimple at the surface of a dermal sinus.9,10 The dermoid or epidermoid cysts may be extradural, intradural, and extramedullary. In the spinal form, the bony deformity of spinal dysraphism can be seen near the tumor on plain x-rays in adults. In children younger than 5 years of age, plain x-rays fail to show spinal dysraphism because the lamina and spinous processes have not yet fully ossified. There may be an increase in interpedicular space on plain films. A tumor located in a more rostral position may be in an intramedullary position, causing a concentric expansion of the spinal cord. Ultrasonography can sometimes be used as a screening study. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has replaced myelography and computed tomography (CT) as the diagnostic study of choice. MRI, although noninvasive, provides great anatomical detail to help make a diagnosis and plan treatment. The dermal tumor is often associated with spinal dysraphism and functionally with tethered cord syndrome. In addition, separate from the dermal sinus, an inelastic filum terminale continuous to the distal spinal cord is typically found attached to the caudally located area of dural schisis. The dermal sinus tract at this region alone can be another factor to cause tethered cord syndrome. Simply removing a dermoid cyst by itself might not be enough to reverse neurological impairment unless other mechanical tethering factors are eliminated. These lesions tend to have anomalous anatomical structures, and at times the true tethering point must be determined among multiple areas of suspected tethering. Case 1 A 1-year, 11-month-old female presented with pain in the back. She had a past history of fevers treated with antibiotics but had never been diagnosed as having had meningitis. She would scream when she sat down hard. She could not tolerate sitting on a carpeted floor. She would not ever sit with her legs crossed or akimbo. She was unable to sleep through the night for 1 week prior to her admission because of low back pain. She exhibited a positive Gower sign where she would not bend over at the waist or hips to pick up objects from the floor. A lumbosacral angioma and tandem spinal dimples were noted. Otherwise she was neurologically intact. At surgery tandem dermoid cysts were resected. The dural sinus stalk was excised, and the filum terminale was divided cephalic to the dural schisis, which was contiguous with the dural sinus (Fig. 14.1A,B). She was pain free after the surgery. Fig. 14.1 Case 1. (A) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing a dermoid tumor just caudal to the conus medullaris causing some distortion of the nerve roots at the cauda equina. (B) MRI in the same patient showing a small caudally located tandem dermoid cyst associated with a dermal sinus. The rostral dermoid tumor is faintly outlined, and the conus medullaris is not seen as well as in (A). Fig. 14.2 Case 2. (A) Dermal sinus at lumbar region with subtle cutaneous angioma. (B) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing the cutaneous dimple, a dermal sinus connecting with a dural reflection or stalk. (C) MRI showing the low-lying conus in the same patient. An 11-year-old male had complained of bilateral foot pain at the age of 6 years. He had been seen in the orthopedic surgery clinic at age 9. He was unable to catch up with his friends when they were running. He was noted to have slightly high arches of both feet and was given a prescription for custom-molded inserts for his shoes. Purulent material was noted to be coming out of a dimple in his back 2 years later and he was referred to the pediatric neurosurgery clinic. There was no history of meningitis and he had no complaint of back pain. A lumbar dimple was noted overlying the midline (Fig. 14.2A). MRI showed a sacral dermal sinus tract as well as a low-lying conus medullaris at the L3–4 region (Fig. 14.2B,C). At surgery (10/14/04) there was a dermal sinus tract extending from the cutaneous dimple into the spinal canal in the sacral region. The dermal sinus was resected, and the filum terminale was divided cephalic to its attachments in the fibrous region of the dural schisis. He remains neurologically intact without pain. Case 3 A 7-month-old male presented with diarrhea and urinary retention requiring catheterization. During his hospitalization he developed fevers to 103°F and was noted to have stopped being as vigorous with his legs. He was noted to have a flaccid paraplegia. Lumbar puncture was attempted but yielded two dry taps. During the attempted lumbar punctures the patient was noted to have a small (1.5 cm diameter) cutaneous angioma in the midline at the lumbar spine. Close examination revealed a dimple in the center of the cutaneous angioma. MRI showed a dermal sinus at the sacral level with abnormal densities in the region of the cauda equina with a swollen appearing cord more superiorly (Fig. 14.3). On 7/3/04 a T9 through S3 multilevel laminotomy was conducted. Pus was drained from the gluteal, the paraspinous regions, extradural, intradural and from the intramedullary regions via myelotomy. A dermal sinus was identified and resected, and the inelastic filum terminale was divided. Postoperatively the patient was noted to have an ascending paralysis that involved his arms. Another MRI scan revealed extension of intramedullary fluid to the cervical region. A multilevel laminotomy was performed from C7 through T3 on 7/8/04. Pus was again obtained via a myelotomy, and the region was irrigated with saline. Anaerobic Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Peptostrepto-coccus magnus were isolated from the spinal cultures. Diphtheroids were isolated from a transrectal drainage of a presacral abscess. Gradually he regained the use of his arms and legs. Fig. 14.3 Case 3. (A) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing lumbar cystic fluid densities distorting normal cauda equina with a dermal sinus going toward the subcutaneous and cutaneous region dorsally. (B) Intramedullary abscess in the same patient extending to the upper cervical spine at the C5 level. Case 4 An 11-month-old female was noted to have a sacral dimple. She was referred to the pediatric neurosurgery clinic. A lumbar cutaneous angioma was noted to be associated with a midline dimple. Her legs were symmetrical and she walked without difficulty. MRI revealed a dural stalk associated with a dermal sinus tract (Fig. 14.4). On 4/16/04 she underwent L4, L5, and S1 laminotomy with resection of the dural stalk for untethering of the spinal cord. A laminoplasty was performed at L4–5. On her postoperative visit of 10/27/04 she was noted to be neurologically intact with no difficulty with voiding.

Case Reports

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree