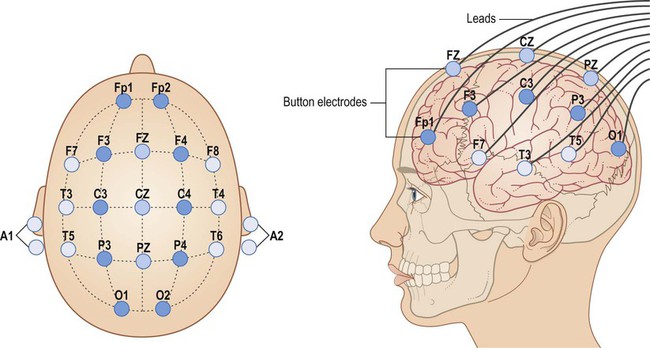

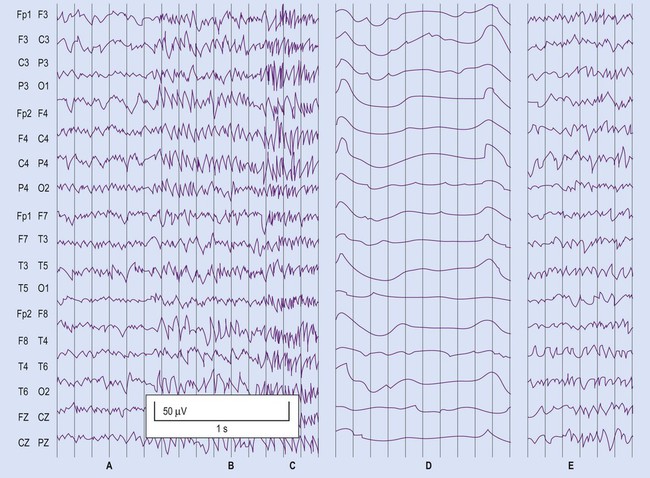

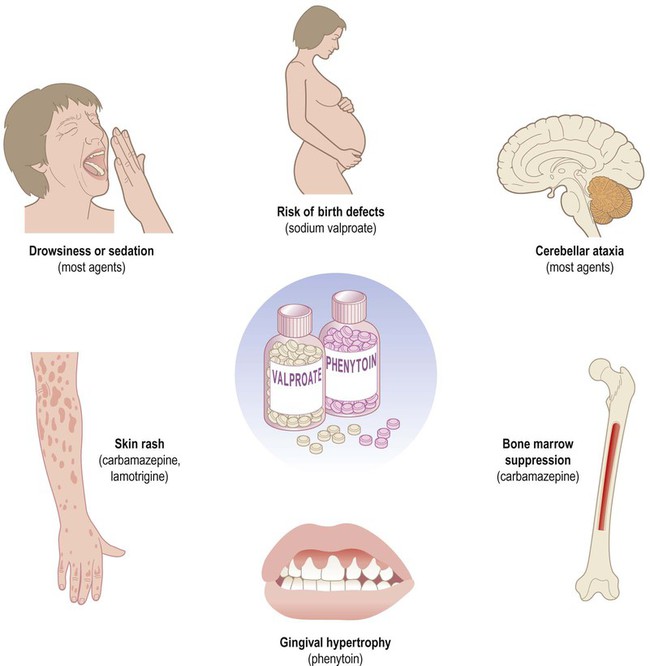

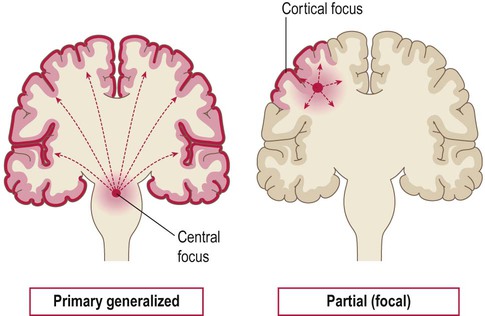

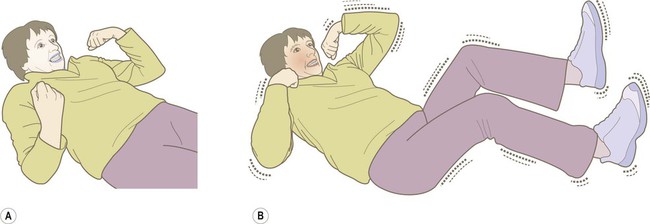

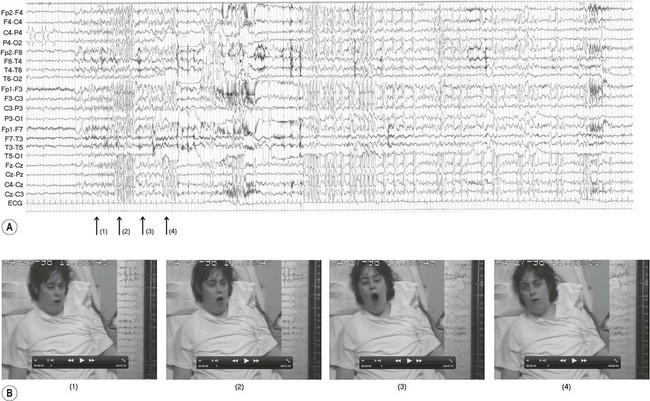

The two main types of seizure are illustrated in Fig. 11.1. Primary generalized seizures diffusely involve both cerebral hemispheres at onset and consciousness is usually lost. Partial (focal) seizures have a discrete cortical origin and the clinical features reflect the function of the affected area. Abnormal electrical activity can often be recorded during a seizure using scalp electrodes (discussed below). There are numerous epilepsy syndromes with differences in seizure type, age at onset, presumed aetiology and EEG findings (Clinical Box 11.1). They can be classified in different ways such as mode of onset (generalized versus focal) or age at presentation. Many epilepsy syndromes arise in childhood and some have highly characteristic features (Clinical Boxes 11.2, 11.3 & 11.4). Despite the large number of epilepsy syndromes, there are several commonly encountered types of seizure, each with distinctive semiology (clinical manifestations). An example of a simple partial seizure has been described in Clinical Box 11.2; in the following sections, typical features of a complex partial seizure and two very different forms of primary generalized seizure will be described. Intense neuronal discharges from the cerebral cortex cause the entire body to become rigid (Fig. 11.4A). Spasm of the laryngeal and respiratory muscles forces air out of the chest, often producing an epileptic cry. The eyes deviate upwards and the patient falls stiffly to the ground, remaining in a state of tonic muscular contraction. Breathing ceases temporarily, leading to cyanosis. This is characterized by violent, symmetrical convulsions, with muscular contraction and relaxation (Fig. 11.4B). Breathing is noisy and poorly coordinated, with salivation that appears as ‘frothing at the mouth’. The face may be pink and congested or cyanosis may persist if ventilation is poor. Tongue biting and other injuries sometimes occur and the patient may be incontinent of urine. As the clonic phase comes to an end the jerking movements gradually subside. The diagnosis of epilepsy is clinical and requires a detailed eyewitness account of the episodes. If EEG is performed, this may provide evidence to support the clinical diagnosis. Video recording combined with EEG (referred to as telemetry) may be particularly helpful in difficult cases (Fig. 11.5). Epilepsy can usually be managed pharmacologically, but a neurosurgical procedure may be suitable in a minority of cases. In some patients, the less invasive option of a vagus nerve stimulator may be considered (Clinical Box 11.5). Two thirds of patients can be managed effectively with anti-epileptic drugs and adequate control is usually achieved with a single agent (monotherapy). Some of the important side effects of anti-epileptic drugs are discussed in Clinical Box 11.6. Inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels is the most common mechanism. This interferes with the depolarization phase of the action potential, which is mediated by a fast inward sodium (Na+) current. Many agents prolong channel inactivation by preferentially binding to sodium channels in their inactivated state. This increases the refractory period of the neuronal membrane (see Ch. 6). Repetitive neuronal firing at high frequencies is specifically reduced (activity-dependence), minimizing interference with normal brain activity. Examples of agents that block sodium channels include: phenytoin, carbamazepine, sodium valproate and lamotrigine. These drugs increase activity at inhibitory synapses (see Ch. 7). Some act via post-synaptic GABAA receptors which are linked to a chloride ion channel; this stabilizes the neuronal membrane via an inward chloride (Cl–) current. These include (i) benzodiazepines (e.g. clonazepam, diazepam) which increase the frequency of channel opening and (ii) barbiturates (e.g. primidone, phenobarbital) which increase the duration of channel opening. Others act at metabotropic (G-protein-coupled) GABAB receptors which influence second messenger cascades; this causes longer-lasting hyperpolarization of the neuronal membrane by opening potassium channels. Several anti-epileptic agents increase the amount of GABA available by modulating its synthesis (sodium valproate), reuptake (tiagabine), release (gabapentin) or breakdown (vigabatrin).

Epilepsy

Types of seizure

Primary generalized seizures originate from a central focus in the thalamus or brain stem and involve both cerebral hemispheres at onset. Partial (focal) seizures begin in a discrete cortical region and are due to an abnormality in the neighbouring grey or white matter. A focal seizure may spread to become secondarily generalized.

General aspects

Common seizure patterns

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures

Tonic phase (30 seconds)

(A) The tonic phase lasts around 30 seconds. The entire body becomes rigid, respiration ceases and the patient becomes cyanotic; (B) The clonic (jerking) phase is characterized by violent symmetrical convulsions, often associated with laboured breathing and frothing at the mouth, typically lasting around 60 seconds.

Clonic phase (60 seconds)

Diagnosis and management

The EEG trace (A) and video sequence (B) capture an ictal event, characterized by involuntary orofacial movements. From Specchio, N et al: Epilepsy and Behavior: Ictal yawning in a patient with drug-resistant focal epilepsy: Video/EEG documentation and review of literature reports. Epilep Behav 2011 Nov; 22(3):602–605 with permission.

Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs)

Mechanisms of action

Sodium channel antagonists

GABA potentiators

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Epilepsy

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue