Seizure is the manifestation of a sudden, uncontrolled surge of neuronal firing. After a first

seizure, approximately 50% of the patients will have a second one within 6 months. After two seizures, children have an approximately 80% chance of recurrence (

1).

Epilepsy, recurrent unprovoked seizures, is the most common neurological disorder in children.

Epilepsy affects 0.5% to 1% of children through age 16 years. Each year, 20,000 to 45,000 children are diagnosed with

epilepsy. Of children 5 to 14 years of age, 325,000 are affected with

epilepsy (

2). Child neurologists spend at least 50% of their clinical time caring for patients with

epilepsy because of seizures and their

comorbidity.

Epilepsy is more common in children with mental retardation and other underlying neurological and psychiatric disorders (

3).

Epilepsy of early childhood onset is more likely to indicate an underlying brain disorder than is

epilepsy of middle childhood onset, which is likely to have an unknown or genetic cause (

4,

5).

Neurologists and psychiatrists have common ground not only in diagnosis but also in their prescribing of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). In addition, psychiatrists might be asked to evaluate and treat

epilepsy‘s comorbidities—depression, attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anxiety—before or in conjunction with neurologists (

3).

This chapter reviews (a)

epilepsy and seizures, including their incidence, classification, etiology, and differential diagnosis; (b) AEDs and their effects on seizures and psychiatric disorders; and (c) psychiatric comorbidities of

epilepsy.

Seizure Classification

The International League against

Epilepsy has proposed a classification based on the clinical manifestations of the

seizure and the electroencephalogram (EEG) (

6). It differentiates partial from generalized seizures.

Partial seizures begin locally within a specific brain region, whereas generalized seizures have no clear focal onset. Partial seizures are further divided into those expressed by confusion or mild alteration of consciousness (complex partial) and those without alteration of consciousness (simple partial). Generalized seizures are defined by the presence or absence of the motor activity that accompanies the events, and are typically associated with impairment or a loss of consciousness (

Table 5.1).

Seizures previously referred to as “grand mal” are convulsive, and include tonic, clonic, and tonic-clonic seizures, and seizures that have partial onset with secondary generalization.

The term

grand mal may include seizures that have partial onset with secondary generalization. Thus, defining a

seizure as grand mal or convulsive does not help determine a possible focal onset. However, documenting a partial (focal) onset is crucial in diagnosing localized pathology, such as mesial temporal sclerosis or a tumor. The term

petit mal had been applied to “small seizures” that could include myoclonic seizures or staring spells, which could be either generalized absence or complex partial seizures. The clinical behavior associated with a partial

seizure depends on the area of the brain that is affected; a behavioral or focal motor event will correlate with the cortical area involved. In adolescents, the most common focus for partial seizures is the temporal lobe. Those seizures often begin with an

aura, such as fear or

déjà vu. In young children, extratemporal partial seizures are more common.

NONEPILEPTIC EVENTS

On the other hand, what appears to be a

seizure is occasionally a nonepileptic event, sometimes termed a “

pseudoseizure.” Although these events are paroxysmal and feature altered behavior, they do not produce an alteration on the EEG. Moreover, they often have no identifiable physiological cause and are frequently associated with psychiatric disturbances. In some children and adolescents, sexual or physical abuse has preceded these episodes.

Kotagal et al (

7) reported paroxysmal nonepileptic events in 134 (15.2%) of 883 children and adolescents during a six-year period in the Cleveland Clinic

Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU). In that study, of children 5 to 12 years old, 61 had a diagnosis of nonepileptic events, including conversion disorder (psychogenic seizures),

inattention, daydreaming spells, stereotypic movements, hypnic jerks, or paroxysmal movements. Of those children, 25% had concomitant

epilepsy. Of adolescents, 12 to 18 years old, 48 had nonepileptic events. Of these adolescents, 83% had a conversion disorder and 19% had concomitant

epilepsy. Thus, the demonstration of a nonepileptic behavior does not rule out the presence of

epilepsy.

Having a family review the video-recorded event is a good way to document that the behavior in question represents the “

seizure” reported. In cases of different types of episodes, management is quite difficult.

When both the clinical evaluation and the EEG suggest pseudoseizures, psychiatric consultation is advisable because of the high incidence of underlying psychiatric disorders (

8,

9). Frequently diagnosed nonepileptiform paroxysmal disorders in children and adolescents are listed in

Table 5.2.

Children and adolescents with mental retardation, autism, or other pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) are subject to another diagnostic pitfall. Clinicians may misinterpret

recurrent movements or behaviors (stereotypies) as seizures. In any case, a comprehensive diagnostic assessment from a neurologist may be indicated because children with these disorders may have a high rate of seizures. Similarly, children who are blind or

deaf or both also have stereotypies, some of which are self-stimulating. Overall, the prognosis of nonepileptic events is better in children than in adults (

10).

Etiology and Diagnosis of Childhood Epilepsy

The etiology of childhood

epilepsy is often population-specific. For example, neurocysticercosis commonly causes

epilepsy in citizens of Central America, where cysticercosis is endemic. The age of onset of

epilepsy is also important. For example, children with inborn errors of metabolism, congenital malformations, and perinatal injuries tend to present with

epilepsy at a young age. Genetic factors and head trauma are more common causes in the older child and adolescent. Although various type-specific gene abnormalities cause certain varieties of

epilepsy, it is still unclear why specific mutations, which are associated with

epilepsy, have variable expression, including different ages of onset in members of the same family (

11).

The history and clinical characteristics of the events serve as the basis of the preliminary diagnosis. During a medical history, the physician should inquire whether activities such as staring spells or myoclonic jerks, which might represent seizures, also occur. In a similar fashion, the physician should ask about possible localized symptoms of seizures. For example, the parents may have noted momentary jerking of one limb or conjugate eye deviation prior to the onset of a

seizure.

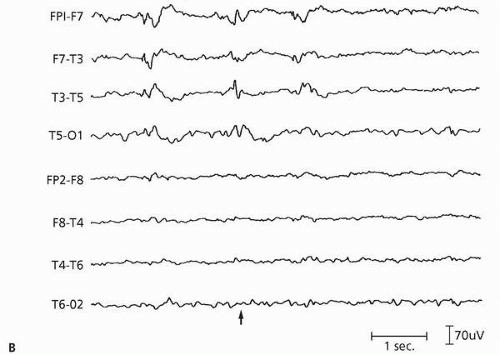

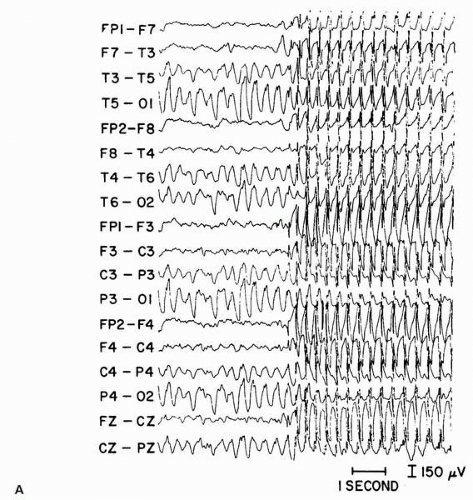

The EEG during the typical episode provides a reliable documentation of the presence, classification, and origin of a

seizure. In the usual clinical situation, a routine EEG is performed between events, that is, in the interictal period (

12). The interictal EEG may be completely normal or may demonstrate abnormalities, such as generalized spike-and-waves or focal spikes, suggestive of generalized or focal onset

epilepsy (

Figs. 5.1A,

B). An EEG may show focal slowing of background rhythms over a particular region, suggesting a structural lesion. EEGs should include photic stimulation and hyperventilation to activate potential epileptiform activity. When clinical events continue despite normal interictal EEGs, neurologists order prolonged (24 hours) EEG studies or an EEG at the time of day when spells usually develop, such as early morning or with sleep deprivation.

Notably, a normal EEG does not exclude a diagnosis of

epilepsy. Moreover, identification of nonspecific abnormalities during a routine EEG does not confirm the diagnosis of

epilepsy. Children’s EEG records have numerous normal variants. For example, young children have prominent, central, sharp vertex activity during drowsiness and sleep that is frequently misinterpreted as being indicative of

epilepsy but is normal.

Prolonged video-EEG monitoring in an EMU for 3 to 7 days is now standard for determining whether seizures are present and establishing an electroclinical correlation. In other words, it determines if a child’s behavior coincides with a paroxysm of abnormal EEG activity. This monitoring confines children to a specially designed room, but within it they are free to move about and a parent can stay with them. EEG electrodes are glued to their scalp rather than secured with pins. In addition to the scalp electrodes, technicians may apply ones to measure other physiological functions, such as respiration, cardiac activity, and ocular movement, which would reflect sleep stages. The monitoring consists of continual digital recordings of closed circuit video observations of children’s behavior and the simultaneous EEG. While the child is in the EMU, physicians often withdraw AEDs to allow

seizure activity to emerge. Although exceptions appear in the literature, the results of video-EEG monitoring are generally accepted as the gold standard.

Neurologists order brain imaging in children in whom cerebral pathology is suspected. However, certain “

benign epilepsy syndromes,” such as childhood absence (see further on), do not require imaging. When imaging is performed,

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice (

12). Advanced imaging techniques, such as functional MRI (fMRI),

positron emission tomography (PET), and other specialized imaging techniques, are currently appropriate only for those undergoing evaluation for

epilepsy surgery.