26

Epilepsy After Sixty

Introduction

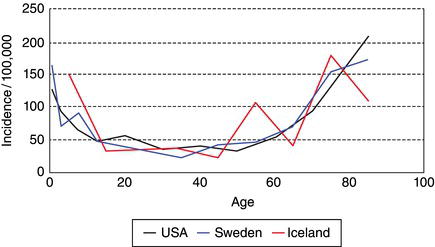

After age 60, the incidence of new-onset seizures rises steeply. Surveys in varied populations revealed incidence rates of about 100/100,000 per year at age 70 and 150/100,000 per year at age 80 (Figure 26.1). Based on nationwide Medicare diagnostic coding data, there is an incidence of 108/100,000 of new-onset seizures for patients 65 and older, translating to over 60,000 new cases per year in the USA. These figures are striking and will increase with an aging population and greater longevity. Prevalence is less than the expected accumulated incidence, suggesting that death rates among elderly patients with seizures are high. Important differences from epilepsy in younger adults are summarized in Table 26.1.

Diagnosis

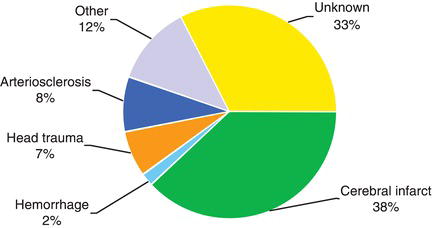

Focal seizures with altered awareness (complex partial seizures) are the most common seizure type in the elderly (Figure 26.2). Unfortunately, these brief staring spells may go unnoticed or be dismissed as inattention or forgetfulness. Automatisms become less prominent with aging, so the seizures may be manifested merely by bland staring.

Therefore, a high index of suspicion coupled with a careful eyewitness description is essential. Routine EEG is helpful if abnormal, but the yield of epileptiform abnormalities, 28%, is less than in younger adults. Continuous video–EEG monitoring either at home or in the hospital is a reasonable option, though expensive. Home cell phone video is surprisingly helpful, though seizure onset is usually missed.

Another factor that contributes to the underdiagnosis of seizures in the elderly is that the differential diagnosis is long and difficult. Included in this differential list are transient cerebral ischemia (TIA), syncope (vasovagal, orthostatic, cardiac dysrhythmia, aortic stenosis, etc.), migraine, metabolic conditions, and psychogenic events.

It is common for seizures to be misdiagnosed as TIAs. It should be noted that TIAs usually produce negative motor phenomena such as weakness. In contrast, motor phenomena during seizures, if present, are positive, as with increased tone or clonus. Transient loss of consciousness is uncommon with TIA. Transient global amnesia usually lasts much longer than does a complex partial seizure.

Syncope is heralded by premonitory symptoms followed by the loss of body tone and a quick recovery. The premonitory symptoms of light-headedness, visual change, and nausea are uncommon for seizures. Syncope may involve some clonic jerking or even a full tonic–clonic sequence—this is “convulsive syncope,” not epilepsy.

Figure 26.1. Incidence of unprovoked seizures in developed countries. From Cloyd J, Hauser W, Towne A, et al. Epidemiological and medical aspects of epilepsy in the elderly. Epilepsy Res 2006; 68(Suppl. 1):S39–S48, with permission.

Table 26.1. Major features of epilepsy in older adults.

| Seizures are very common; incidence increases with age over 60 |

| Cerebrovascular disease is the most likely cause |

| Complex partial seizures predominate and are difficult to diagnose |

| A first seizure is likely to recur |

| Drugs must be used at lower dosages |

| The seizures are often easy to control |

Figure 26.2. Etiology of seizures in patients over the age of 60 (VA Cooperative Study). From Ramsay RE, Rowan AJ, Pryor FM. Special considerations in treating the elderly patient with epilepsy. Neurology 2004; 62(5 Suppl. 2):S24–S29, with permission.

Etiology

The most common identifiable cause of new-onset seizures after age 60 is cerebrovascular disease (Figure 26.3). Embolic, hemorrhagic, large, or cortical strokes are most likely to cause seizures. About 10% of strokes are followed by seizures, with about half occurring “early” (often defined as within 2 weeks) and half “late.” This differentiation has prognostic significance and therefore influences decisions about treatment.

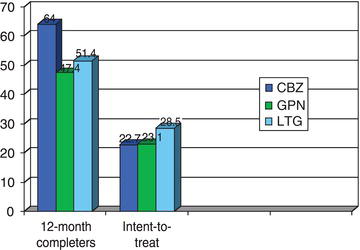

Figure 26.3. Percentage of patients seizure-free at 12 months, VA new-onset geriatric epilepsy study. From Rowan AJ, Ramsay RE, Collins JF, et al. New onset geriatric epilepsy: A randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. Neurology 2005; 64:1868–1873, with permission.

SCIENCE REVISITED

SCIENCE REVISITED CAUTION!

CAUTION! CAUTION!

CAUTION!Alzheimer’s disease is a risk factor for seizures, with up to 10% incidence, usually late in the course. Of the metabolic causes, hyperglycemia can cause partial as well as generalized-onset seizures. Hypoglycemia more often produces syncope or other symptoms recognizable by the patient as low-sugar related. Many prescription drugs carry warnings of seizures, but in practice this association is infrequent. Occasionally bupropion, maprotiline, tramadol, theophyllines, thorazine, fluoroquinolones, or other drugs can be implicated, usually in association with large doses. Other antibiotics, neuroleptics, and antidepressants rarely cause trouble, and if indicated, they should not be withheld. Alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal is suspected if heavy consumption and then abstention is followed in 24–72 h by seizure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree