Epilepsy: Historical Perspectives

Michael D. Daras

Peter F. Bladin

Mervyn J. Eadie

David Millett

|

(The fact is that the cause of this affection is in the brain.)

Hippocrates: On the Sacred Disease133

Introduction

Among the diseases that have plagued humans over the centuries, few exhibit the brief, frightening manifestations of an epileptic attack and the relatively quick, seemingly miraculous recovery. Accounts of what may have been epileptic seizures can be found in several ancient scriptural accounts such as reference to the prophet Balaam falling down with the eyes open (Numbers, XXIV, 1) and to King Saul’s fits of rage (Samuel I, 18, 10 and 19,9). While naphal and nôphêl were Old Testament and Talmudic terms for epilepsy, Israelites also used nikpheh to refer to the disease.201,204 Similarly, the prohibition against entering the temple by those possessed by a malevolent power in the ancient Egyptian text of Esra has also been thought to be a reference to epilepsy.218 In contrast, the papyrus of Ebers, the oldest Egyptian medical book, has no mention of the condition. Initially, these ancient accounts of falling attacks attributed such “seizures” to an evil entity or punishment inflicted by a god or, later, to some natural cause. Not until Hippocrates was the origin of epilepsy placed in the brain. Temkin, in his book The Falling Sickness, describes a battle between rational, scientific thinking and magical beliefs that started with Hippocrates’ connection of epilepsy to the brain and continued at least until Jackson’s time.232

Sakkiku

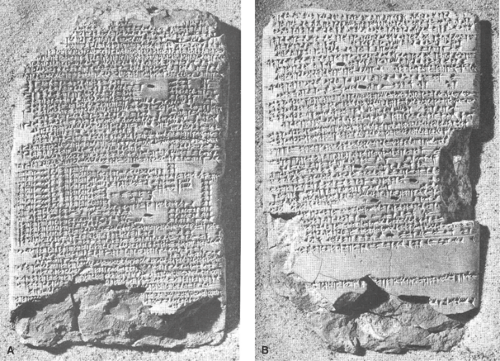

The oldest medical reference to epilepsy consists of two clay tablets written in Assyrian-Babylonian, which are copies of portions of a comprehensive medical textbook known as Sakkiku that dates to the reign of King Adad-apla-iddina (1067–1046 BCE). The tablets were discovered during separate archaeologic expeditions in Turkey and Iraq (Fig. 1A, B); they were subsequently translated by Wilson and Reynolds.248 Although written over 3,000 years ago, they provide remarkably accurate accounts of some characteristic clinical manifestations of the disease.

“It is he again!” probably implies an aura. Descriptions of seizure phenomena include generalized convulsions; repetitive occurrence as in status epilepticus; partial motor seizures (“his eyes roll to the side, a lip puckers, and his left hand, leg and trunk jerk”); adversive attacks and sensory symptoms, such as auditory hallucinations; and epigastric aura. Gelastic epilepsy was reported for the first time: “[If at the] time of his epilepsy he laughs loudly for a long time, his legs (his hands and legs) being continuously flexed and extended.” The impressive astuteness of the clinical observations is matched by a detailed description of various demons that were considered responsible for each symptom. Interestingly, there is no discussion of treatment.

China

Epilepsy was apparently known in ancient China, but no chapter devoted to epilepsy is known to exist in the ancient Chinese medical literature. Lai and Lai161 presented the information offered on epilepsy in Huang Di Nei Jing (The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine), a collective work of Chinese physicians that was compiled between 770 and 221 BC. In the Ling Shu volume the term dian-kuang was applied to a generalized attack preceded by behavioral alterations. At first, this term was used interchangeably for epilepsy and psychosis, but the two entities were differentiated around 200 BCE in the medical text Nan Jing.161 Epilepsy was generally considered congenital, but other causes including phlegm and insufficiency of blood or kidney were mentioned. Treatment was focused on restoring the balance between the energies, the yang from the sun and the yin from the moon, or among the five elements metal, wood, water, fire, and earth that were considered disturbed during disease states.

India

The three ancient Indian medical systems of Siddha, Ayurveda, and Unani all recognized epilepsy.226 The most elaborate descriptions are found in the Ayurveda (science of life), the oldest known medical system that evolved continuously from 4500 to 1500 BCE. The views on epilepsy are attributed to the physician Atreya (about 900 BCE). The compendium of Ayurvedic medicine known as Charaka Samhita (6th century BCE) used the term apasmara (apa, loss of; smara, consciousness or memory) for epilepsy.19 Visual hallucinations; twitching of the tongue, eyes, and eyebrows; and jerking of the hands and feet accompanied by excessive salivation were some of the symptoms noted, as well as the observation of a patient awakening after the attack as if from sleep.176 The term Apasmara poorva roopa was used for auras that included visual, auditory, and somatic symptoms, as well as behavioral disturbances.

The Ayurvedic system attempted to classify seizures into four types based on the defects in one the three doshas (humors). It also recognized external trigger factors such as high fever, internal bleeding, extreme mental agitation, and even excessive sexual intercourse. In addition to the traditional Ayurvedic approach to treat the whole body (physical, mental, and spiritual), cleansing through enemas, purgation, or emesis as well as medicinal preparations based on herbs were employed.

Hippocrates

The Hippocratic treatise On the Sacred Disease133 is not a medical text; it was apparently written for the layperson. It begins with an attack against common popular superstitions

and all those who labeled epilepsy as “sacred” to conceal their ignorance about its cause and justify their fraudulent practices. Contrary to the Babylonian text, the Hippocratic writings challenged the widespread beliefs of the time that epileptic seizures were caused by actions of demons or gods. The Babylonian text described in detail various epileptic symptoms, as caused by a particular demon, while Hippocrates (Fig. 2) attempted to disconnect the physical phenomena from supernatural forces. After a brief description of the generalized epileptic attack, the author recognized the hereditary nature of the disease and the greater frequency with which children were affected.

and all those who labeled epilepsy as “sacred” to conceal their ignorance about its cause and justify their fraudulent practices. Contrary to the Babylonian text, the Hippocratic writings challenged the widespread beliefs of the time that epileptic seizures were caused by actions of demons or gods. The Babylonian text described in detail various epileptic symptoms, as caused by a particular demon, while Hippocrates (Fig. 2) attempted to disconnect the physical phenomena from supernatural forces. After a brief description of the generalized epileptic attack, the author recognized the hereditary nature of the disease and the greater frequency with which children were affected.

The fundamental difference, however, between Hippocrates’ and other contemporary or older medical explanations (Assyrian, Indian, and Chinese) lies in the unequivocal statement about the origin of the disease: “the fact…that the cause of this affection (epilepsy)… is in the brain.” Hippocrates further recognized that all cognitive functions or emotional manifestations are related to the brain, emphasizing that “men ought to know that from the brain, and from the brain only, arise our pleasures, joys, laughter and jests, as well as our sorrows, pains, grieves and tears. Through it, in particular we think, see, hear and distinguish the ugly from the beautiful, the bad from the good, the pleasant from the unpleasant…” Thus, Hippocrates importantly dissociated epilepsy from religion and magic, arguing forcibly and eloquently that epilepsy was properly a subject not for incantation but for medical investigation and study.

FIGURE 2. Hippocrates (c. 460–377 BCE), presumed author of the essay On The Sacred Disease. (Museo della Via Ostiense, Rome.) |

His explanation that phlegm rushes into the cerebral vessels, preventing air from flowing into the brain, was the first attempt to explain the cause of epilepsy based on a physiologic process that affected the brain. Another important Hippocratic contribution to medicine was the introduction of prognosis. In the essay On the Sacred Disease, he commented on

the grave outcome of status epilepticus and the spontaneous remission of epilepsy in children as they mature. In Wounds of the Head, Hippocrates for the first time recognized laterality in brain function,134 when he described trauma to the temple as producing spasm of the contralateral limbs. In his attempt to prove that there was nothing “sacred” about epilepsy, Hippocrates stated that there was treatment for the disease, but no specific suggestions occur in his writings.

the grave outcome of status epilepticus and the spontaneous remission of epilepsy in children as they mature. In Wounds of the Head, Hippocrates for the first time recognized laterality in brain function,134 when he described trauma to the temple as producing spasm of the contralateral limbs. In his attempt to prove that there was nothing “sacred” about epilepsy, Hippocrates stated that there was treatment for the disease, but no specific suggestions occur in his writings.

Post-Hippocratic Hellenistic and Roman Medicine

Attempts to define epilepsy started during Hellenistic times and continued during the time of the Roman Empire. The description of questionable authenticity,232 attributed to the Alexandrian physician Erasistratus (3rd century BCE), “that epilepsy is a convulsion of the body together with an impairment of the leading functions” emphasized two cardinal symptoms, convulsions and loss of consciousness. An interesting observation of that time was that sensory stimuli such as bad smell133 or the sight of whirling wheels5 were potentially epileptogenic. Greeks and Romans used this knowledge to evaluate the fitness of slaves being sold by having them face the sun while looking through a turning potter’s wheel. Intermittent photic stimuli produced by his marching soldiers were reported to have triggered some of Julius Caesar’s attacks.

Among those in the 1st and 2nd century CE whose writings have survived are Soranus of Ephesus and Celsus in Rome. Our knowledge of medical attitudes during the post-Hippocratic, pre-Christian era, from the 4th century BCE on, is limited to the information available from Soranus through Caelius Aurelianus.47 None of Soranus’ works in Greek have survived. It is believed, however, that the 5th-century CE physician, Caelius Aurelianus, preserved them in Latin translation. These writings contain an extensive list of symptoms that could precede epileptic attacks, including excessive sexual excitement accompanied by sexual acts (possibly seizures of frontal lobe origin), and they also discuss psychic causes, such as fright and anger, as precipitating factors. The seriousness of repetitive attacks was noted, and physicians were advised to warn relatives about their severity and lack of treatment to avoid possible repercussions after a patient’s death. Consumption of wine was associated with seizures, and even drunkenness of the wet nurse was implicated as a cause of epileptic seizures in children. Soranus criticized Hippocrates’ statement about the existence of treatment, when none was mentioned in the Sacred Disease. Soranus also attacked contemporary practices like Diocles’ use of various substances in enemas, or the administration of animal or human excrements by Praxagoras, Asclepiades, and Serapion. Patients whose attacks had a predictable pattern of recurrence were bled in anticipation and purged with emetics (white hellebore) or cathartics (scammony or black hellebore). This type of “catharsis” was popular by Greek and Roman physicians from 300 BCE to 100 CE.47

Celsus in the Comitialis, Book III, 2354 described both generalized convulsions and what were probably atonic and myoclonic attacks. He noted that epilepsy was more common among men and children but added that onset in childhood was associated with a better prognosis. He never discussed possible causes but advised dietary measures and avoidance of cold, heat, and wine, and opposed the practice of administering blood of dead gladiators.

In the 2nd century CE, the two main contributors to epileptology were Galen of Pergamon and Aretaeus of Cappadocia. Unlike Hippocrates, whose description of seizures in the essay On the Sacred Disease emphasized only major symptoms, Aretaeus provided a detailed narrative of generalized convulsions6:

“The man lies unresponsive with the arms in spasm and the legs stiffened and then shaking; the head is twisted, either bent to the sternum or backwards as if pulled violently by the hair; the mouth is open with the tongue protruding at risk of being injured or cut; the eyes are turned upwards, while the lids blink; if they are not closed, the white of the eye shows; the face is distorted and changed, because the eyebrows frown or are pulled to the temples; the lips either protrude or are pulled to the side and shake; the initial redness of the face is replaced by paleness; the blood vessels of the neck dilate; the pulses are initially fast and then slow; towards the end there is loss of urine and feces or in some men ejaculation, while froth comes from the mouth.”

Further recognizing the variety with which epilepsy could express itself, he stated: “Epilepsy is an illness of various shapes and horrible.” Without using the term, he described a visual aura—“red or black lights or both together appear in arcs before the eyes, similar to the rainbow”—and gave a detailed list of auditory (ringing in the ears), olfactory (foul smell), and other sensory symptoms. Like Hippocrates, Aretaeus observed the greater frequency with which seizures occurred in children as compared to adults, as well as the spontaneous remission in old age: “If it passes the peak of life, it co-ages and dies out.” Todd paralysis, first observed by Hippocrates, was termed “paretic hand” by Aretaeus.

Galen’s descriptions of epileptic seizures43,99,224,231 are scattered throughout his works and include “loss of consciousness and the leading functions,…sudden fall,…the presence of spasms, or sometimes (loss of consciousness) in the absence of them,…secretion of froth from the mouth,…loss of urine,…ejaculation,…changes in pulse rate.” He apparently did not restrict the diagnosis of epilepsy to generalized convulsions as he wrote “if there is not only convulsion, but also interruption of the leading functions, then this is called epilepsy.” Galen differentiated types of seizures based on their clinical features and the anatomic part involved in the aura. His classification of seizures as primary (originating in the brain) or sympathetic (arising either from the stomach or from other parts of the body) was the first and influenced the approach to epilepsy for centuries. Galen also noted the more frequent occurrence in childhood, a relation between seizures and the menstrual cycle, and the precipitation of seizures by prolonged starvation. Galen is credited with introducing the term aura (in Greek, sea breeze), which he described in a young man who reported the feeling of a “cool aura” that started in his foot, marched upward, and heralded the onset of the attack.100

Treatment in the Hellenistic and Roman times was guided by the theories of three schools: The dogmatic—Galen and Aretaeus (based on the pathology of the disease), the empiric—Serapion, and the methodist—Soranus, Themison, and Celsus. What was common to all three schools was the importance of dietary regimens, exercise, sleep, and “catharsis” through emetics, enemas, or bleeding. Various techniques of bleeding and cauterization of the arteries of the scalp, as well as trephination, were used. Both methodists, such as Theodorus Priscianus, and dogmatists, such as Aretaeus, recommended these methods. Soranus, however, and later the Galenist Alexander of Tralles, warned against them, “which to many become a punishment rather than a cure.”231 The use of drugs for epilepsy probably preceded the dietetic treatments that required time and money, and thus were affordable only by the rich. It is, therefore, not surprising that a large number of drugs were developed. Dioscurides (2nd century CE) in his Materia Medica76 lists 45 antiepileptic substances. Temkin231 divided them into three categories: 18 had no connection to magic and corresponded to contemporary pathologic theories; at least 13 were definitely based on superstition; and 14 had no apparent magical connotation, but the reason for their use was questionable.

Byzantine Medicine

The transfer of the capital of the Empire from Rome to Constantinople in 330 CE marked the transition from the Roman to the Byzantine Empire. The corresponding religious transformation led to significant changes in medical attitudes. While hospitals were built particularly for the care of the poor, religious views changed society’s attitude toward medicine. In the case of epilepsy, the description of the miraculous cure of the “lunatic” boy by Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel (17:14–18) heralded a return to pre-Hippocratic beliefs of demonic possession. Origen, one of the early Fathers of the Church, stated, “Physicians physiologize, as they do not consider it [epilepsy] to be a dirty spirit, but a somatic symptom… This disease should be considered to be the influence of a dirty, speechless and evil spirit.”190 Supporters of this view included St. Athanasius, John Chrysostom, and Hieronymus in the West.174 The “lunar influence” on epileptics, which was considered by ancient physicians to be the result of humoral changes of the brain, was explained as the devil’s attempt to defame God by defaming his creation. In the Eastern Church it was not until several centuries later that the Alexandrine Stefanus of Athens and the 11th century Patriarch Photios in his Amphilochia settled this argument in favor of a naturalistic explanation.173 Among physicians, however, a “biologic” approach to epilepsy based on the Hippocratic and Galenic tradition was retained throughout the thousand years of the Byzantine Empire. The Encyclopedists Oribasius, Aetius Amidenus, Alexander of Tralles, and Paul of Aegina preserved and organized the works of earlier Greek and Roman physicians.83 Support for epilepsy as a natural disease is indicated by the comments of Leo (9th century CE) that “epilepsy occurs from obstruction of the ventricles of the brain”; Psellos (11th century CE) that “epilepsy is a spasm obstructing the exits for the psychic spirit. It may start at another part, like the hand or the foot as an aura that rises to the brain”; and Actuarius (14th century CE) that it is “a disease…due to a fine dyscrasia of the brain or the presence of bilious humor in its ventricles.”83,174

Oribasius, physician to the last pagan emperor Julian the Apostate, attempted to challenge religious views on the influence of the moon on epilepsy by arguing “as the sun…warms the bodies, so the moon rather moistens them… It makes the brains wetter…and triggers epilepsy.”83,189 Aetius Amidenus (6th century CE), chief physician to emperor Justinian, interpreted the fear that preceded the attacks: “the so called terror is not a demon but intention and preface to epilepsy.”3,83 Influenced by Galen, Alexander of Tralles (6th century CE) classified epilepsy into “primary, originating in the brain, one originating from the stomach and a third from other parts of the body, which subsequently reaches the brain.” He considered loss of consciousness as the main symptom of the attack but included complex partial seizures as “they get wearied on the head, confused, hard of hearing and sense slowly before the attack.” He should be credited with the first description of reading epilepsy: “I observed a man falling while reading who sensed the attack from a cold aura starting in the tarsus and rising up to the brain.”4 Paulus Aegineta (7th century CE) defined epilepsy as “a spasm of the whole body with damage of all princely functions.” He explained the prodromal symptoms as “an unintentional tension of the soul [that] precedes the epileptic [attack], and dysthymia and oblivion of the future and tumultuous dream visions and headache and continuous head fullness, and irritability with paleness of the face and disorderly movements of the tongue.” Paulus noted the possible lethality of the attacks in childhood but also the occasional spontaneous remission after puberty. He recommended abstinence from alcohol “…particularly the old and heavy wines” and sexual intercourse, because orgasm and epilepsy were considered equivalent.194 Treatment of epilepsy included the use of various drugs and again “catharsis” through emetics, enemas, and venesection.83

Contributions from Islamic Medicine

The influence of earlier Persian, Indian, and particularly Greek (notably Hippocrates and Galen) practices set the foundations for Islamic medicine. A reference of a god telling Zoroaster to prohibit epileptics from offering sacrifices in his honor is probably the only mention of epilepsy from the ancient Persian religion. The translation of Greek words resulted in new Persian-Arabic medical terms such as abilibsyâ (usually referring to the psychic symptoms) or Sar (connoting falling sickness).240 Islamic medicine, like Byzantine, was strongly influenced by Galenic beliefs. The two main Islamic physicians who mostly influenced the West were Rhazes (865–925 CE) and Avicenna (980–1037 CE). Their opinions were based on personal observations of epileptic phenomena. Avicenna in his Canon deviated from Galenic opinions by not considering convulsions as essential. He defined epilepsy as a sickness that prevented animation of the members, the operation of the senses, movement, and standing erect.243 Although he invoked the Galenic concept of ventricular obstruction, he differed in concluding that the lower (fourth) ventricle, and not the anterior ventricles, was the area of obstruction by an unhealthy humor, usually phlegm. He considered two possible mechanisms, one originating in the brain and the other in the nerves, proposing that a putrid vapor from the distal part rose to affect the brain. Rhazes used bleeding, emetics, and purgatives, while Avicenna used several traditional herbal and other pharmacologic agents.

Medieval Europe

The Middle Ages started earlier in the Western Roman world than in the East. Fragments of the works of Soranus and Caelius Aurelianus provided concise descriptions of epilepsy. Cassius Felix (5th century CE) recapitulated the old opinions that epilepsy was divided in two types: One accompanied by convulsions, the other by sleep. Like Galen, Cassius Felix believed that seizures originated in the brain due to influence of a melancholic humor or phlegm, the stomach, or any lower part of the body.50 He used “epilepsy” to refer to the idiopathic type originating in the brain, whereas “analepsy” was the type “ascending” from the stomach, and “cataplexy” the type arising from other parts. Cataplexy, however, was used differently in ancient writings to describe a condition with fever and mental obtundation.11

The translation of classical Greek and Arabic texts into Latin and the establishment of medical studies influenced the beliefs of medieval scholastic medicine. Based on older traditions and their own observations, physicians were quite familiar with convulsive epilepsy as well as some of the other forms. Bernard of Goddon (14th century CE)165 described brief episodes of loss of consciousness and staring spells. The classification of epileptic symptoms was a matter of considerable discussion and description, with the main question centered on how to find the original lesion. Platearius (12th century CE) distinguished between “major and minor epilepsy” in a way reminiscent of the later distinction between “grand mal and petit mal” epilepsy.231 Another division involved “true” (Galen’s “idiopathic”) versus “spurious” (originating from other parts) types of epilepsy. Arnold of Villanova (14th century CE) blamed phlegm for the “true” and black bile mixed with phlegm for “spurious” epilepsy.243 Gilbertus Anglicus231 agreed on phlegm as the cause of “true” epilepsy, but he suggested other humors as the cause of the “spurious” form. John

of Gaddesden164 wrote of three forms: Minor or true (due to obstruction of the arteries to the brain), medium or truer (due to obstruction of the nerves), and major or truest epilepsy (due to obstruction of the ventricles). Significant disagreements existed among medieval authors about the type of humors involved in different forms of epilepsy based on arbitrary or even imaginary signs such as the viscosity of the saliva or the color of the urine. Medieval physicians recognized trauma as a cause of epilepsy probably based on the Hippocratic observation in the Wounds of the Head. Alī ibn Abbās and Constantinus Africanus associated seizures with fractures of the skull and compression of the brain. Both early Arab and European physicians emphasized the hereditary nature of epilepsy as noted in the essay On the Sacred Disease.

of Gaddesden164 wrote of three forms: Minor or true (due to obstruction of the arteries to the brain), medium or truer (due to obstruction of the nerves), and major or truest epilepsy (due to obstruction of the ventricles). Significant disagreements existed among medieval authors about the type of humors involved in different forms of epilepsy based on arbitrary or even imaginary signs such as the viscosity of the saliva or the color of the urine. Medieval physicians recognized trauma as a cause of epilepsy probably based on the Hippocratic observation in the Wounds of the Head. Alī ibn Abbās and Constantinus Africanus associated seizures with fractures of the skull and compression of the brain. Both early Arab and European physicians emphasized the hereditary nature of epilepsy as noted in the essay On the Sacred Disease.

During medieval times, Western European, Byzantine Greek, and Arab physicians did not significantly extend the boundaries of our understanding of epilepsy. At a time, however, of prevailing beliefs in falling evil and demonic possession, they deserve recognition for maintaining the tradition of understanding disease in terms of natural causes.231

Medieval China

Classification of seizures was published in Chinese medical books in the 7th century CE based on the Chinese philosophy of medicine and the belief of “yang and yin” energy and disturbances of their balance. Nowhere was the brain mentioned as being involved in epilepsy. The goal of the treatment was to expel the wind and the phlegm, bring down the fever, activate blood circulation, and energize the kidneys and spleen. The therapy included herbs, acupuncture, mai yao (injection of herbs into acupuncture points), mai xien (inserting a piece of goat intestine into the acupuncture point), and massage.161

Pre-Colombian America

Although three major cultures, Inca, Aztec, and Mayan, flourished across the Atlantic, little documentation survived the colonization. The Inca term for epilepsy in the Quechua language (sonko-nanay) was rather erroneously translated by the Spanish chroniclers as “mal de corazon.” The term sonko means the center of the human body and mind located in the chest and upper abdomen and not heart (corazon), and nanay means disease. Variations of this term were used to describe different symptoms: songo-piti (pulling the heart) and songo-chiriray (getting frozen) for grand mal seizures, nahuin-ampin (darkening of vision) and upayacurin (behavioral arrest) for partial simple seizures, and upakundiya (upa, fool; kontiyak, volcanic) for complex seizures.46 While the Incas considered epilepsy to be divine punishment, epileptics were considered closer to the supernatural forces. On the other hand, the Aztecs believed epilepsy was related to the influence of evil goddess Cihuapipiltin; children were not allowed to go out on the days of her descent to earth. As in the Greco-Roman world, slaves with epilepsy could not be sold.84

The American cultures used religious-magical means as well as the administration of products from plants, animals, or minerals to treat epilepsy. Both Aztecs and Incas employed removal of sin by washing and confession. The ritual of Bacabs (evil deities) was practiced by the Mayans, who invoked the help of good deities against them.180 Constituents of magical means, such as hair from a corpse, a stag’s horn, a dog’s bile, or the brain of an ox or weasel, were part of the Aztec remedies. A large number of plants were used for epilepsy on an empirical basis but, unfortunately, none of them was included in a study that evaluated medicinal plants from Central and South America.191

The Renaissance

During the Renaissance the beliefs in supernatural or physical causes continued in their separate ways. Physicians believed that bilateral tonic–clonic seizures, often associated with falling to the ground, were the sole manifestation of epilepsy. Nonetheless, there were occasional suggestions that epilepsy might include less dramatic events. Antonio Benivieni15 described an obvious complex partial seizure without either falling or secondary convulsing and made it clear that he considered this a form of epilepsy that was probably unfamiliar to his contemporaries. In 1470, the Chinese author Fang Xian161 wrote of olfactory auras and visual hallucinations preceding loss of consciousness without specifying that either falling or bilateral convulsing necessarily followed.

Paracelsus (1493–1541) discussed the falling sickness in his posthumously published Diseases That Deprive Man of His Reason that was written between 1520 and 1525.242 He defined five varieties of epilepsy, beginning in the brain, liver, heart, intestine, and limbs, thus extending Galen’s three. He tended to think in terms of alchemical processes and perceived resemblances between seizures and earthquakes. In the falling sickness the “vital spirits” of the body, like an earthquake, suddenly boiled up at the site of the apparent origin of the attack and then spread to other parts. Once they reached the brain, consciousness was lost. Such a concept, mounting to sudden spontaneous overactivity in some organs body, though highly fanciful, accurately conveyed the potential violence of the epileptic process. It reflected his belief that epilepsy had a natural rather than a supernatural origin. His disciple, van Helmont (1570–1644), further proposed that nearly all seizures originated in the stomach, where the local Archeus (the soul, or ruler of that organ) had become injured and angry.192 This idea was subsequently abandoned, but Paracelsus’ concept that seizures arose from abrupt overactivity in some parts of the body was adopted, refined, and—a century later—restricted to the brain by Willis.

Paracelsus proposed new chemical remedies for epilepsy, many of them of mineral origin, including his allegedly efficacious green vitriolic oil. The chemical nature of these treatments remains obscure largely because the source material cannot be determined and, therefore, they cannot be reproduced. Both their claimed mechanisms of action and alleged efficacy appear highly speculative.

The Scientific Revolution

During the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, some present-day authors have identified, though not fully convincingly, what could be regarded as the first descriptions of certain epileptic syndromes, such as benign Rolandic epilepsy by Martinus Rolandus in 1597,238 focal motor (jacksonian) seizures by the philosopher John Locke in 1676,194 and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy by Thomas Willis in 1667.79

Thomas Willis (1621–1675) was the main contributor to epileptology during this period. The evolution of his thinking about the subject can be traced in two separate publications: Thomas Willis’ Oxford Lectures75 preserved by Lower and Locke, who kept notes of his lectures between 1661 and 1664 that were published three centuries later, and Pathologie Cerebri.247 Willis’ account of hysteria contained descriptions of what would appear to be epileptic manifestations, including the paroxysmal events that befell his “very noble lady of a most curious shape,” who may have suffered from juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. It is likely that generations of authors, perhaps going back to Plato himself, mistakenly attributed instances of a rising abdominal discomfort to hysteria, when in reality these

were the epigastric auras of temporal lobe epilepsy. Willis at least realized that hysteria could occur in men and concluded that it arose in the brain and not in the uterus. At autopsy his “very noble lady” whose seizures were “hysterical” had a macroscopically normal uterus, but Willis believed there were abnormalities in her brain.

were the epigastric auras of temporal lobe epilepsy. Willis at least realized that hysteria could occur in men and concluded that it arose in the brain and not in the uterus. At autopsy his “very noble lady” whose seizures were “hysterical” had a macroscopically normal uterus, but Willis believed there were abnormalities in her brain.

Willis tended to diagnose epilepsy only when the sufferer was afflicted with “insensibility, and horrid convulsions, and also with foam at the mouth.” He regarded preliminary symptoms, such as fits of “vertigo or giddiness” associated with confusion, as precursors to, rather than as manifestations of, the seizure. His theories explain epilepsy as movement of the “animal spirits,” an intangible entity whose existence had been invoked in the time of Galen as the psychic pneuma,207 and which had been employed ever since to explain nervous system activity. In the period between 1661 and 1664, Willis suggested that epileptic seizures arose from contraction of meninges that squeezed the “animal spirits” from the brain into the peripheral nerves, producing widespread muscle contractions. Later in his Oxford lectures, he spoke of a chemically induced boiling of these “animal spirits” causing the postulated meningeal contraction. At that time he also suggested that the sensory aura produced the actual seizure through the centripetal movement of these spirits that started the aura and also activated a central epileptic explosive mechanism in the brain. By 1667, Willis abandoned the notion of meningeal contractions because he recognized that this was an anatomic improbability due to the dura’s firm attachment to the skull. In his final explanation of seizure causation, he concluded that the decisive event was an explosion of animal spirits in the center of the brain. This explosion in the brain caused loss of consciousness, and its force set up a sequential series of chemically initiated explosions in the “animal spirits” radiating centrifugally. When the explosions reached the origin of the peripheral nerves, it produced a tugging on the nerves that resulted in abrupt muscle contractions. Willis continued to believe that centripetal movement of “animal spirits” associated with the experience of an epileptic aura could trigger an explosion in the center of the brain, producing a convulsive seizure. Alternatively, he also thought that local explosions near the origin of a peripheral nerve could be the cause of the aura itself, suggesting that a sensory aura might be of central and not peripheral origin.

Willis produced a “comprehensive” hypothesis of the origin of epileptic seizures based on speculations of an intangible entity, “the animal spirits,” whose physical existence had already been questioned by his contemporaries, Harvey,127 Stensen,228 and Glisson.116 Ingenious though it was, Willis’ line of thought was not developed further by his successors, though it contained the seeds of ideas that reappeared in the latter half of the 19th century. Through his theories of epilepsy causation, Willis reasoned his way to a rational approach to treating and preventing seizures. In practice, however, this approach justified the use of the multiple conventional antiepileptic remedies of his day, whose application in practice he described in detail in the Pathologie Cerebri.

The 18th Century

The period of the Enlightenment saw a gradual replacement of the notion of the “animal spirits” as the explanation for neural activity, although it was still employed as late as 1770 by Tissot and 1779 by Morgagni. Concepts such as Cullen’s brain “energy”70 or Haller’s “irritability”125 began to be used as the mechanism of neural function. A year after Galvani’s discovery of electricity in 1780, Fontana began to write of the “electrical fluid” in nervous tissue.36 However, the concept of an electrical component was not to be applied to ideas about epilepsy for some time.

During the 18th century, diagnosis of epilepsy generally required the presence of both loss of consciousness and bilateral convulsive activity. Cheyne,56 however, seemed to imply that falling (presumably from loss of consciousness) might suffice for the diagnosis. Tissot232 provided a reasonably convincing description of what Calmeil48 later called absence seizures: “these ‘petits’ being accompanied at times by grande accés,” while Cullen in 178970 recognized the existence of partial convulsions involving only a localized part of the body with preservation of consciousness that distinguished them from epilepsy: “I might treat of particular convulsions, which are to be distinguished from epilepsy by their being more partial: That is, affecting certain parts of the body only; and by their not being attended with a loss of sense, nor ending in such a comatose state as epilepsy always does.” Heberden in his Commentaries,129 perhaps following Tissot, wrote of brief minor depressions of consciousness in relation to epilepsy, as well as the familiar bilateral tonic–clonic seizures. By then the clinical spectrum of epilepsy was beginning to widen. It was generally accepted that the origin of epilepsy was located in the brain, but there was little consideration of more precise localization. Boerhaave27 wrote of “too great an action of the brain” as the basis of the epileptic seizure, while Cullen70 attributed it to an excess of brain energy, confessing that he was unable to be more specific. Curiously, Tissot,232 in his thorough review of the earlier literature on epilepsy, reverted to Willis’ notion that brain contraction expelled the “animal spirits” and caused seizures.

The 18th century saw the development of interest in the pathologic basis of epilepsy. Morgagni,183 using his experience in neuropathology, suggested that epileptic seizures arose from structural abnormalities of the brain such as hardening (gliosis) or abscess, which diverted the “animal spirits” from their normal pathways through the brain substance or released an irritant that acted on these spirits to produce seizures. The growing interest in the neuropathologic basis of epilepsy was also reflected in attempts to classify the epilepsies according to the pathology.27,70 Various structural pathologies as well as inheritance, strong emotions, and speculative chemical abnormalities were included in the causes. The details of these classifications are less important than the fact that etiology and structural pathology had become crucial in the attempt to understand the pathogenesis of epilepsy. Outside of the medical circles, however, beliefs of supernatural influences still persisted.

Gradually some of the more extreme, if not outrageous, remedies of the past began to disappear during the 18th century. Measures such as venesection continued to be used, and the antiepileptic pharmacopoeia became increasingly botanical in nature. Tissot reviewed these treatments232 and commended valerian more highly than any of its numerous alternatives. Indeed, in appropriate types of seizures and at sufficient dosage, valerian may have had some chemical basis for genuine antiepileptic efficacy.80

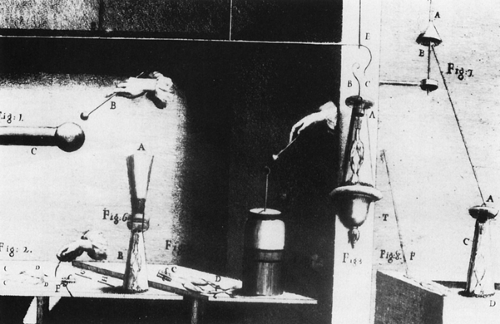

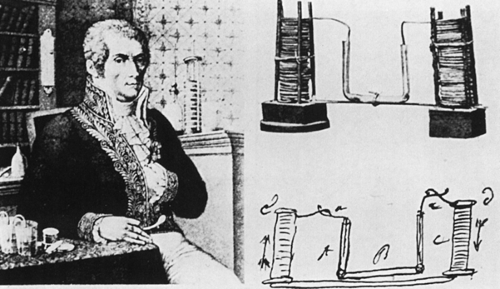

Biologic Electricity

Luigi Galvani (Fig. 3) created the foundation for the field of electrophysiology and, ultimately, electroencephalography through his monumental discovery of animal electricity in 1791.101 These fruits of his work would revolutionize the study of epilepsy in the 20th century. Galvani demonstrated that electrical charges produced by friction and stored in Leyden glass jars caused muscle contractions, whether the charge was applied to the muscle or the nerve (Fig. 4). For many years, Galvani’s seminal observations had little scientific impact, in spite of confirmation of the phenomenon by Alessandro Volta (Fig. 5) and others. In fact, it was Volta, inventor of the first storage battery, who was largely responsible for the 50-year delay in the general acceptance of animal electricity because of his misinterpretation of Galvani’s experimental findings. Volta

incorrectly and tenaciously ascribed all of Galvani’s evidence of intrinsic nerve transmission to direct muscle stimulation from a battery effect due to the inadvertent use of two dissimilar metals.241 Galvani, who opposed Napoleon, lost his position at the University of Bologna and the Institute of Sciences, while Volta, a supporter of Napoleon, received many honors, and by outliving Galvani by three decades, used his prestige to continue to deny the validity of his countryman’s work. It was not until 1937, 200 years after Galvani’s birth, that Bologna’s Institute of Sciences celebrated his life and republished his treatise.

incorrectly and tenaciously ascribed all of Galvani’s evidence of intrinsic nerve transmission to direct muscle stimulation from a battery effect due to the inadvertent use of two dissimilar metals.241 Galvani, who opposed Napoleon, lost his position at the University of Bologna and the Institute of Sciences, while Volta, a supporter of Napoleon, received many honors, and by outliving Galvani by three decades, used his prestige to continue to deny the validity of his countryman’s work. It was not until 1937, 200 years after Galvani’s birth, that Bologna’s Institute of Sciences celebrated his life and republished his treatise.

The 19th Century

During the 19th century the acceptance of various clinical manifestations of epilepsy broadened considerably. New theories of the mechanisms underlying the origin of epileptic seizures emerged and provided the basis for today’s evolving concepts of epileptogenesis. Supernatural ideas about the origin of epilepsy finally began to fade. Sieveking,225 however, still cited and interpreted Moreau’s statistical study in 1854, on perhaps not entirely justifiable grounds, as finally debunking the ancient belief in a lunar influence on epileptic seizures. And importantly, the first effective antiepileptic drug treatment appeared, almost incidentally, if not frankly, accidentally.

Epileptic Phenomena

In his 1823 review of previous knowledge concerning epilepsy, Cooke67 continued to insist that loss of consciousness and bilateral tonic–clonic seizures were required for diagnosis. From that time on, however, most authors, while still requiring transient loss of consciousness, have not emphasized bilateral convulsive behavior as a prerequisite for the diagnosis of epilepsy.39,87,124,205,216,234 Thus, at the end of the 19th century, Beevor14 could write that “epilepsy is the name given to sudden loss of consciousness with or without convulsions.”

This change in diagnostic requirements triggered an increased interest in the minor manifestations of epilepsy such as the brief losses of consciousness that Tissot232 had described, termed by Calmeil48 as “absences” and by Esquirol87 as “petit mal.” Prichard205 had included these, along with superficially similar episodes characterized by a prodrome of which the patient was aware (i.e., simple partial seizures evolving into complex partial ones) in his subtype of “leiothymia,” a term that soon disappeared from use. He also described a tetanic type of epilepsy, probably the same or similar to present-day tonic seizures, and wrote of “partial epilepsy” largely in Cullen’s70 sense of epileptic manifestations appearing only in a part of the body without alteration of consciousness. New epileptic

syndromes were described: First Bravais35 and later Bright39 and Todd234 reported focal motor seizures, before Jackson made them the subject of his special interest, and which Charcot later55 associated with Jackson’s name. Todd, and before him Bright, noted the temporary “epileptic hemiplegia” after such focal seizures and which later became known as Todd paralysis. West245 described infantile spasms, sadly, in his own infant son, while Herpin132 provided a detailed account of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy but did not regard it as a separate entity within the “commotions” (i.e., myoclonic seizures). An increasing wealth of detail about the prodromes or auras became available in the literature, and Esquirol87 recognized their occasional occurrence as isolated events without other manifestations of epilepsy. Herpin132 considered the aura to be not a warning but rather the actual start of the seizure: “la première manifestation de l’attaque.”

syndromes were described: First Bravais35 and later Bright39 and Todd234 reported focal motor seizures, before Jackson made them the subject of his special interest, and which Charcot later55 associated with Jackson’s name. Todd, and before him Bright, noted the temporary “epileptic hemiplegia” after such focal seizures and which later became known as Todd paralysis. West245 described infantile spasms, sadly, in his own infant son, while Herpin132 provided a detailed account of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy but did not regard it as a separate entity within the “commotions” (i.e., myoclonic seizures). An increasing wealth of detail about the prodromes or auras became available in the literature, and Esquirol87 recognized their occasional occurrence as isolated events without other manifestations of epilepsy. Herpin132 considered the aura to be not a warning but rather the actual start of the seizure: “la première manifestation de l’attaque.”

At the same time that a diverse and expanded repertoire of epileptic seizures was being recognized, there was a growing effort to define and limit those phenomena that could legitimately be included under the rubric of epilepsy. This latter development arose from an increasing attempt to classify diseases on an etiologic basis. At the onset of the 19th century, Maisonneuve174 and later Prichard205 divided epilepsy into idiopathic and sympathetic types, with the latter further subdivided into gastric, intestinal, hysterical, and hypochondriacal subtypes, based on the part of the body where the first seizure manifestation was experienced. Esquirol87 added a third type, a symptomatic form of epilepsy due to disease outside the central nervous system. Delasiauve73 utilized the same three main categories, but his idiopathic epilepsy was restricted to cases of cerebral origin without brain pathology, while his symptomatic type was characterized by detectable cerebral pathology. Shortly thereafter, Reynolds,213 in his 1861 monograph on Epilepsy: Its Symptoms, Treatment, and Relation to Other Chronic Convulsive Diseases, defined an entity of “epilepsy proper,” which meant cases without obvious brain pathology. Seizures due to detectable cerebral, or extracerebral, pathology were termed epileptiform and not epileptic. Unfortunately, defining epilepsy as a disease whose cause was the absence of a detectable cause was virtually guaranteed not to have enduring validity as knowledge advanced. Two decades later, Gowers121 extended this concept of epilepsy, almost surreptitiously, when he used the term epilepsy to refer to all seizures of cerebral origin without “active” pathology. Contemporaneously, new hypotheses of epileptic mechanisms emerged. In the first third of the century, seizures were commonly ascribed to brain hyperemia or venous congestion.67,87,205 while Mansford175 postulated that cerebral plethora caused charged electrical fluid to accumulate in the brain until it could no longer be contained, thus triggering a brain discharge and an epileptic seizure. Romberg216 accepted both brain plethora and brain anemia as being capable of producing seizures. As an outcome of his study of the neural mechanisms underlying the reflex arc, Hall123 postulated that excessive activity in the afferent limb of the reflex arc (eccentric epilepsy) or in the central element (centric epilepsy) produced the excessive motor response comprising the convulsion. He proposed that the initial convulsive tightening of the muscles of the neck and larynx obstructed the cerebral venous return, causing brain congestion that led to loss of consciousness. Hall’s interpretation did not account for epileptic auras and meant that bilateral convulsive movements began before consciousness was altered, contrary to the usual sequence of events in a seizure. Brown-Séquard45 overcame these difficulties by postulating that excessive afferent activity, which was sometimes also responsible for the aura, in the central nervous system ascended to structures as high as the medulla oblongata. Upon reaching the medulla it produced a discharge at the medullary vasomotor center, which caused immediate cerebral arterial spasm leading to loss of consciousness. Reynolds213 combined elements of both Hall’s and Brown-Séquard’s ideas, proposing that Brown-Séquard’s mechanisms initiated the seizure, while Hall’s mechanism of venous obstruction mechanism perpetuated the unconscious state with the resultant hypercapnia from cessation of breathing converting the initial tonic convulsion into clonic jerking.

Gradually these postulated mechanisms had become acceptable in explaining convulsive seizures and placed the central events in the medulla oblongata. Van Sweiten’ data239 also settled on the medulla as the critical brain region involved in epileptogenesis, while Sauvages219 and Nothnagel187 had claimed the production of convulsions in animals by stimulating the medulla. Kussmaul and Tenner160 reported convulsions in experimental animals after rapidly exsanguinating them and through sections at different levels of the central nervous system showed that an intact brainstem in continuity with the spinal cord was essential for such anoxic convulsions to occur.

In his animal experiments, Todd (1809–1860)234 found that electrical stimulation of the spinal cord or the medulla produced tonic spasm of muscles and stimulation of the mesencephalon produced clonic convulsions, but stimulation of the cerebral hemispheres led only to slight facial twitching. On this basis he postulated that epileptic seizures arose in the cerebral hemispheres much like a discharge of static electricity from a condenser. If the discharge was restricted to the hemispheres, consciousness was lost but no motor symptoms occurred. If, however, the discharge reached the midbrain, clonic convulsive movements occurred in addition to loss of consciousness, but if it extended into the medulla and spinal cord, tonic components followed. Thus, Todd accounted for all of the elements of the convulsive epileptic seizure, except for the aura. He did not address epileptic unconsciousness without motor accompaniment. His ideas, however, did not attract a following among his contemporaries.

In contrast to all of these concepts that were based on brain overactivity, Radcliffe208 attempted to explain epileptic seizures as a manifestation of reduced neural activity. His ideas received a courteous reception, but were otherwise ignored and never developed further. Thus, by 1860, plausible explanations were available for the mechanisms underlying most aspects of epileptic phenomena, and a consensus had developed that the medulla oblongata was the critical brain region in the production of epileptic seizures. That state of knowledge formed the background against which John Hughlings Jackson’s work over the next 40 years was carried out.

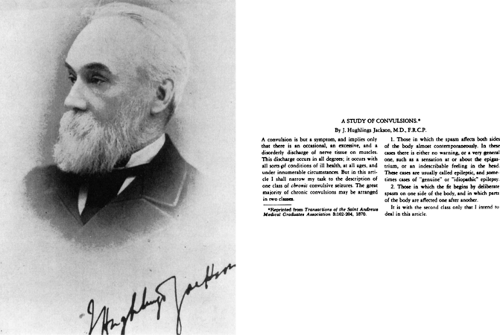

John Hughlings Jackson (1835–1911)

In the 1860s, Jackson68 (Fig. 6) set out to analyze and then interpret the mechanisms underlying epileptic seizures. His numerous writings were compiled by Taylor.230 Jackson, who initially attempted to study bilateral tonic–clonic seizures, soon realized that these were too widespread, developed too rapidly to be followed reliably by the observer, and the patient, being unconscious, could contribute little information. He therefore decided to first try to study focal motor seizures, as events were more localized and easier to follow, and the patient could often describe the experience. Such seizures were sometimes followed by temporary hemiplegia similar to that due to lesions in the internal capsule rather than the brainstem. Spenser’s psychology had prepared Jackson for the idea of localization of function within the cerebral hemisphere, although it had not yet been demonstrated. By the mid-1860s, Jackson had named focal motor seizures “corpus striatum epilepsy,” as he had perceived that they probably began in neuronal cell bodies in the neighboring striatal gray matter, which had become functionally overactive.

By 1870, after considering Broca’s40,41,42 reports of aphasia from lesions in the posterior-inferior left frontal convolution, Jackson observed that temporary dysphasia occasionally coexisted with Todd paralysis after focal motor seizures involving the right face, and the association of focal motor seizures sometimes with syphilitic nodules in the meninges over the contralateral middle cerebral artery. Jackson142 concluded that focal motor seizures involving the face or hand probably originated in the lower part of the perirolandic cortex of the opposite cerebral hemisphere. This radical departure from the conventional interpretation of the site of epileptogenesis received independent support within a comparatively short period from Fritsch and Hitzig’s experimental studies of cortical stimulation and ablation in animals.98 This work provided convincing evidence of localized representation of motor function within the cerebral cortex. During the next few years Jackson’s concept of epilepsy became increasingly wide ranging:

“Epilepsy is not one particular grouping of symptoms occurring occasionally; it is a name for any sort of nervous symptom or group of symptoms occurring occasionally from local discharge… A paroxysm of ‘subjective’ sensation of smell is an epilepsy as much as is a paroxysm of convulsion; each is a result of sudden local discharge of grey matter.”

Jackson’s idea that all convulsions and epileptic manifestations were symptoms was at first criticized on the grounds that he had not studied “epilepsy proper,” but merely one variety of epileptiform seizure. His reaction to this criticism consisted of convoluted and rather repetitive writing, in which he continued to draw a distinction between focal motor seizures and “epilepsy proper” to make his ideas more acceptable to his peers, in spite of his private belief that they were manifestations of epilepsy and even occasionally saying so.

In the 1870s experimental physiologists, such as Ferrier,90,91,92 began to map out aspects of localization of function in the animal cerebral cortex. At the same time Jackson started to pay attention to the minor, often paroxysmal, expressions of human epilepsy. He used the knowledge of the site of pathology in conjunction with the experimental animal findings to locate sites for the representation of various functions within the human cerebral cortex. He accumulated data suggesting that the foot was represented in the upper part of the perirolandic cortex,145 and that the site responsible for auditory hallucinations and the so-called dreamy state or “intellectual aura” was in the anterior part of the temporal lobe.146,147 Jackson related visual hallucinations to the posterior half of the cerebral hemisphere without being able to more precisely localize the site of their origin. He deduced that consciousness depended on intact function of an extensive part of the prefrontal cortex of at least one hemisphere.143 He attempted to explain the cortical origin of epileptic auras using these localizations and the belief that an epileptic discharge arose from a sudden release (at times he used the word “explosion”) of local brain energy. If the localized discharge achieved sufficient intensity and extent of spread, the aura would progress to unconsciousness and even convulsing. Extensive involvement of the prefrontal cortex by the discharge caused loss of consciousness, while involvement

of the cortical motor areas produced contralateral convulsing. Jackson had originally thought144 that unilateral motor cortex discharges might finally activate the uncrossed pyramidal pathway, and thus convert contralateral convulsing into bilateral convulsing. Later, following Horsley’s experiments,140 Jackson accepted the idea that the discharge must cross the corpus callosum and other brain commissures for bilateral convulsive movements to occur.

of the cortical motor areas produced contralateral convulsing. Jackson had originally thought144 that unilateral motor cortex discharges might finally activate the uncrossed pyramidal pathway, and thus convert contralateral convulsing into bilateral convulsing. Later, following Horsley’s experiments,140 Jackson accepted the idea that the discharge must cross the corpus callosum and other brain commissures for bilateral convulsive movements to occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree