chapter 7

Episodic Disturbances of Neurological Function

The assessment of patients with intermittent disturbances of neurological function is one of the most interesting and challenging aspects of clinical neurology. One needs to be an amateur detective like Sherlock Holmes, whom Arthur Conan Doyle modelled on Dr Joseph Bell, one of his teachers at the medical school of Edinburgh University. Dr Bell was a master at observation, logic, deduction and diagnosis [1]. This chapter discusses the various causes of episodic disturbance of neurological function. There is only a brief discussion of epilepsy and cerebrovascular disease as they are covered in more detail in Chapter 8, ‘Seizures and epilepsy’, and Chapter 10, ‘Cerebrovascular disease’, respectively. Vertigo is discussed in this chapter as most often it is an episodic disturbance, but mainly because it seemed to fit better in this chapter than in any other.

THE HISTORY AND INTERMITTENT DISTURBANCES

Most inexperienced clinicians simply ascertain the nature of the symptoms. They do not determine their exact distribution, the mode of onset and progression of each and every symptom, particularly in relation to the other symptoms, nor the circumstances under which symptoms occur, which often provides the vital clue to the diagnosis.

The recommended method of taking a history is different from that described in Chapter 2, ‘The neurological history’. It is far more useful to ask the patient to provide a detailed account of several individual episodes.

As you take the history question the patient about the symptoms:

A suggested method of history taking

Begin by asking the patient the following questions:

1. Tell me about the last episode you had: what were you doing at the time it commenced?

2. What was the very first symptom that you noticed?

3. From the moment you first noticed that symptom, was it at its most severe or did it become more intense or spread to involve other parts of the body?

4. If it did, how long did it take to spread or reach maximum intensity?

6. What was the next symptom that you noticed?

7. How long after the first symptom did it commence?

8. Was the initial symptom showing signs of improving or worsening before this symptom began?

9. How long did this symptom take to develop in terms of maximum intensity or extent of involvement of the body?

Cases involving single episodes

On the surface this does appear to be an epileptic seizure preceded by an olfactory aura (see Chapter 8, ‘Seizures and epilepsy’, for further discussion of the term ‘aura’, which is used to describe the initial symptom(s) of a seizure, often referred to as the warning symptoms). However, this doctor was too quick in jumping to the diagnosis of epilepsy and used only the nature of the symptoms to make a diagnosis, recalling that some seizures are associated with an altered smell. The correct diagnosis was apparent when a detailed history was obtained.

Cases involving recurrent episodes or transient symptoms

In patients with recurrent episodes or transient neurological symptoms, establish whether all episodes were identical and whether the symptoms varied from one episode to another by asking: ‘Are all your turns the same or are some different to the others?’ If the episodes varied, it is more rewarding to ask about several individual episodes. This is most relevant in some patients with epilepsy who may have multiple types of seizures (see Chapter 8, ‘Seizures and epilepsy’). If the events were all identical, it is possible to use the approach of asking the patient to imagine having an episode right now in front of you and using the questioning technique described above to obtain a detailed description of each and every symptom. This approach could miss the diagnosis when the circumstances under which these episodes occurred provide the vital clue to the diagnosis. This is highlighted by the next two cases.

Note the same error: only the nature of the symptoms was obtained. The weakness in all four limbs combined with true vertigo (the room spinning), diplopia (double vision) and dysarthria (slurred speech) clearly points to involvement of the brain stem. The intermittent nature of the symptoms combined with the age of the patient suggests the diagnosis of vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI, transient cerebral ischaemia in the posterior circulation). To the experienced clinician the transient loss of consciousness (LOC) in two of the episodes is atypical and would raise doubts about this being primarily related to cerebral vascular disease. (LOC is extremely rare in patients with VBI. See Chapter 10, ‘Cerebrovascular disease’.)

A more detailed history obtained the vital clue.

The detailed description of the three individual events revealed that they all occurred with exercise, and cerebral ischaemia related to vascular disease does not occur in such a predictable manner.1 Examination of the patient demonstrated severe aortic stenosis, and the explanation for her symptoms was exercise-induced hypotension due to poor cardiac output with initial selective involvement of the posterior circulation causing the focal symptoms and the subsequent global cerebral ischaemia resulting in LOC.

The patient described in Case 7.4 alerted this author to the importance of obtaining a blow-by-blow description of each of the episodes. She had recently been discharged from hospital without a clear diagnosis and after having undergone extensive investigation over a 2-week period. The patient was an 85-year-old woman who would be called in the trade ‘a poor historian’.

After the patient described two further episodes it became clear that every one occurred about midday and only when she stood up. Six months beforehand she had been placed on prazosin, a drug for hypertension and one that is often associated with postural hypotension. Her blood pressure fell from 170/100 lying to 110/65 on standing and her symptoms resolved upon cessation of this drug.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF CLASSIFICATION OF INTERMITTENT DISTURBANCES

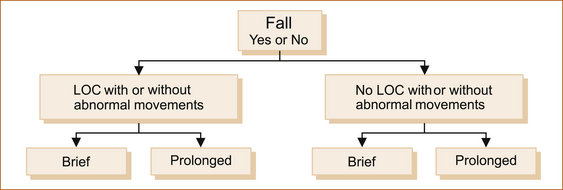

There are many ways to classify intermittent disturbances of neurological function. The traditional approach is to classify them according to the aetiology or underlying pathological basis. On the other hand, the simplest classification from the clinical point of view depends on what can readily be observed during episodes and is shown in Figure 7.1. Patients:

• fall (or slump if seated) or do not fall

• have a ‘blackout’ or they do not, whether they fall or not

• may or may not experience abnormal movements under any of these circumstances

• may experience episodes that vary in duration from seconds to minutes or even hours.

The various causes of intermittent disturbances can be differentiated along these lines.

Most episodes in patients who fall with or without LOC are brief. The exceptions are:

• the very rare prolonged tonic–clonic seizure lasting many minutes

• syncope with a prolonged aura

• a secondary head injury causing LOC complicating the fall, whatever the cause.

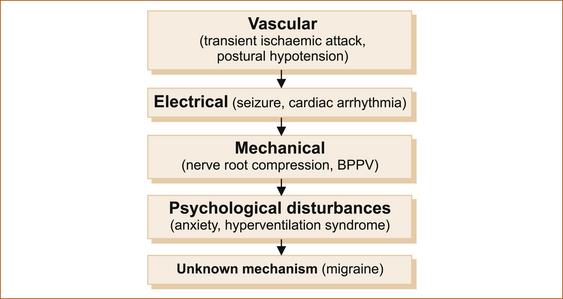

Most intermittent disturbances result from one of the mechanisms illustrated in Figure 7.2.

EPISODIC DISTURBANCES WITH FALLING

Falling with loss of consciousness

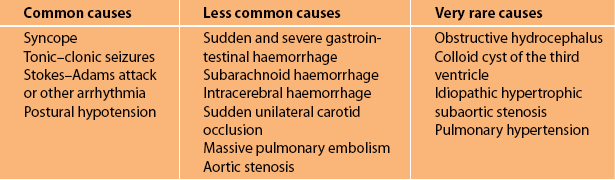

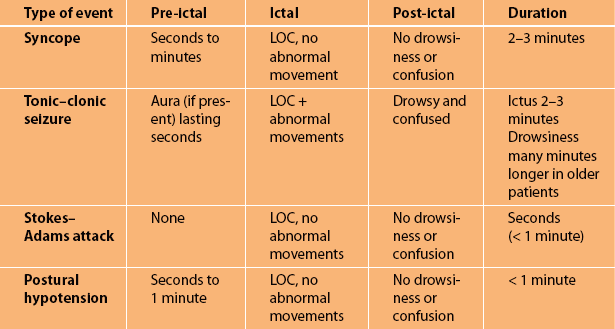

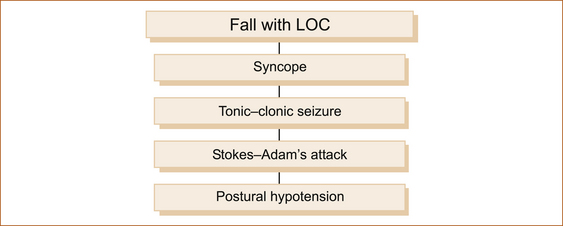

The four most common causes of transient LOC with falling are given in Figure 7.3. A complete summary of the numerous causes of transient LOC associated with a fall are listed in Table 7.1. Table 7.2 summarises the main clinical features of the common causes. Note that all are brief in duration.

Syncope (fainting, vasovagal or neurocardiogenic syncope)

Although syncope can afflict anyone of any age it tends to occur more commonly in young adults [2]. The patient is almost invariably standing, occasionally sitting and very, very rarely in a recumbent position. There is often, but not always, a trigger such as pain, alcohol, stressful situations, the sight of blood or being in a hot crowded environment.

• Immediately before ictus: There are several warning (pre-ictal) symptoms that increase in intensity over a period lasting between 30 seconds and 2 minutes after they first appear. These warning symptoms are referred to as pre-syncope and include light-headedness, nausea and feeling hot and clammy. If the symptoms worsen the patient becomes sweaty, their vision darkens and their hearing dims.

• During ictus: The patient subsequently loses consciousness (ictus), the eyes are closed, they are very pale and there are no abnormal movements unless the patient suffers a secondary seizure that usually consists of a very brief tonic seizure lasting less than 20 seconds. In some patients syncope can occur with little or no warning, mimicking a Stokes–Adams attack (see below). Patients with shorter duration of warning symptoms may suffer traumatic injuries [3].

• After ictus: The patient rapidly regains consciousness (within 10–30 seconds) and, although they wonder what has happened, they are neither confused nor drowsy and can carry on a sensible conversation almost immediately after the episode, even when there has been a brief secondary seizure.

Unlike epilepsy, many patients who suffer from syncope can prevent LOC by lying or sitting down quickly when they experience the warning symptoms. This is an important diagnostic clue. Where there is uncertainty advise the patient to lie down immediately when the episode next occurs to see if LOC can be prevented by elevating the legs so that they are above the level of the head. There is a very rare condition in elderly patients where syncope can be related to carotid sinus sensitivity [4].

SOME NOTES OF CAUTION

1. Patients and eyewitnesses often have difficulty estimating time, and ‘funny turns’ always seem to last longer than they actually do.

2. Pallor by itself is not overly useful, as patients are invariably described as being pale or a dreadful colour with all types of funny turns of differing causes. Having said this, extreme pallor associated with sweating is very suggestive of a cardiovascular cause.

3. Feeling the pulse quickly is very difficult, even for people who are trained such as medical practitioners and nurses; the apparent absence of a pulse does not necessarily imply an arrhythmia.

4. Eyewitnesses and patients often interpret having no recollection of the event as post-ictal confusion.

5. Regarding confusion, it is very important to clarify what observers and patients mean when they say the patient was confused after the episode.

Tonic–clonic seizures

Only a few brief principles are discussed here, as Chapter 8, ‘Seizures and epilepsy’, deals with the subject of epilepsy in detail.

• Immediately before ictus: The pre-ictal phase or aura if present is very brief, lasting only a few seconds. In many patients with tonic–clonic seizures there is no warning before they lose consciousness.

• During ictus: The patient will fall to the ground and there is a brief stiffening of the limbs (tonic phase) lasting 10–20 seconds followed by jerking (clonic phase) of the limbs lasting on average 5–30 seconds. The duration of impaired consciousness is brief. Most tonic–clonic seizures last approximately 1 minute, although they can last as long as 10 minutes [5]. The eyes are usually open during the seizure and observers often say the eyes rolled up into the top of the head. The patient may bite their lip, cheek or tongue and they may suffer incontinence of urine and/or faeces during the seizure.

• After ictus: The post-ictal period is associated with drowsiness and confusion lasting from 30 seconds to several minutes [5]. The period of post-ictal drowsiness and confusion may be as long as 24 hours or even up to 1 week following prolonged seizures and in older patients [6].

Stokes–Adam’s attack

This predominantly occurs in the elderly, although very rarely Stokes–Adam’s attacks can occur in younger patients. These episodes are usually related to a bradyarrhythmia or complete heart block, although similar symptoms can occur with a tachyarrhythmia if it results in sudden hypotension [7].

• Immediately before ictus: There is no warning.

• During ictus: The patient suddenly finds themselves on the ground, wondering what has happened. They do NOT recall falling. The period of impaired consciousness (ictus) is very brief, usually only a matter of seconds, certainly less than 1 minute [8].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree