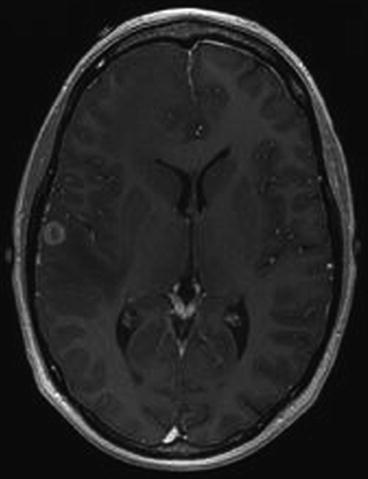

Fig. 12.1

Axial T1-enhanced MRI showing a hemorrhagic metastasis in the right frontal lobe of a 37-year-old woman with metastatic melanoma

Fig. 12.2

A smaller second lesion is seen on another cut

12.3 Approach to the Case

The team approached the case considering available evidence from the literature including as many as possible randomized studies, the patient’s eligibility for ongoing clinical trials, their collected clinical experience, analysis of risks and benefits, and patient preference. The options they listed include:

1.

Whole brain radiation alone (WBRT)

2.

Resection of the larger lesion followed by WBRT

3.

Resection of the larger lesion plus stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to the resection bed and the smaller tumor

4.

Resection of the larger lesion plus stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to the smaller tumor

5.

Resection of both tumors alone

6.

Resection of both tumors followed by WBRT

7.

Resection of both lesions followed by SRS to both resection beds

8.

SRS for both lesions alone

9.

SRS for both lesions followed by WBRT

While there is some validity for all of these options, the team decided on option 4 which the patient accepted, and the treatment plan proceeded without problem.

12.4 Discussion

12.4.1 General Ethical Approach

Rapid evolution and development in neurosurgery has resulted in several different approaches to treat the same neurosurgical problems, and this will increase in the future with the development of more and more sophisticated and complex technologies and treatments. The absence of national or international guidelines, and the lack of class I evidence supporting one method over another for most of the conditions we treat, has given the neurosurgeon the possibility to choose both what he/she feels is best and what is within his/her own capabilities and still offer the best treatment he/she is able to give the patient. Patients may get confused receiving different suggestions. The principle of autonomy dictates that the patient should know everything about the disease and should know the different methods of treatment. Although patients should make the final decision on treatment, it is wrong to presume that they can reach the decision with minimal input from the neurosurgeon. The neurosurgeon should explain all equally successful methods and then state his/her preferred method for treating the case. Ultimately the patient must decide if he/she is willing to undergo the treatment method preferred by the neurosurgeon.

Pearl

Arguably the most important single manifestation of the sacred trust between the patient and surgeon is the course of treatment the surgeon recommends. This trust is truly sacred and the surgeon must bring everything to bear to make the best decisions for his/her patients.

12.4.2 Disease-Specific and Modality-Specific Examples of Sources of Ambiguity in Decision-Making

12.4.2.1 Spine Surgery

In a patient with intractable S1 sciatica and a moderate-sized herniated lumbar disc, should the neurosurgeon try an epidural nerve root block prior to surgery? If it comes to surgery, should a standard microsurgical discectomy be done or a minimally invasive “tubular” discectomy (Dasenbrock et al. 2012)? Is an interbody fusion needed? Should the procedure be done as an outpatient procedure or should the patient be admitted (Purzner et al. 2011)? The same dilemmas exist regarding cervical disc disease. A retrospective database analysis was done to compare the perioperative patient characteristics, early postoperative outcomes, and costs between anterior cervical discectomy and fusion and a cervical total disc replacement surgery in one US center (Nandyala et al. 2014), and they found out that both cohorts demonstrated comparable incidences of early postoperative complications and costs. There were no significant differences in the risks for postoperative complications between the surgical cohorts. There are no fixed proven-beyond-doubt guidelines for spinal instrumentation. A lot depends on the experience of the neurosurgeon and the availability of instrumentation and affordability for patients; the last two factors are particularly relevant for neurosurgeons practicing in the developing world. Some people argue that spinal instrumentation may be being overused and is an industry-driven practice.

12.4.2.2 Gliomas

In a patient with a presumed low-grade glioma, should the patient be treated up front or observed in a “wait and see” protocol (Deekonda and Bernstein 2011; Hayhurst et al. 2011)? Should a biopsy be done either way? If open surgery is opted for, should a radical resection be attempted or as aggressive as the surgeon is comfortable doing? Should the surgery be done under general anesthesia or using awake craniotomy with functional mapping (Kirsch and Bernstein 2012)? Is surgical navigation based on archived imaging sufficient or is operating in an open MRI unit to provide real-time imaging the gold standard? Should the procedure be done as an outpatient procedure, or does the patient require admission to hospital (Purzner et al. 2011)?

Regarding lesions with the imaging features presumed to be high-grade glioma, the imaging findings do not predict the exact pathology in 100 % of these cases. Many times, particularly in the developing world, tuberculoma is also a differential diagnosis. Should all patients presumed to have a tuberculoma which can be treated pharmacologically first have an image-guided biopsy or resection to avoid treating a glioblastoma erroneously (Fath-Ordoubadi et al. 1997)? Should patients with glioblastoma receive, after best standard care (i.e., surgery, radiation, temozolomide), additional therapy with Gliadel wafers, Avastin, or other marginally effective treatments? The surgeon and his/her team can be challenged both when these therapies are used and when they are not used.

12.4.2.3 Aneurysms

In a patient with a subarachnoid hemorrhage, is CT angiography sufficient for surgical planning, or is a catheter angiogram needed? Should an endovascular procedure like coiling be done, or should open surgery be done? If surgery is done is a ventricular drain or lumbar drain needed routinely? Some evidence is available to help guide our approach. The effect of coiling versus clipping of ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysms on length of stay, hospital cost, hospital reimbursement, and surgeon reimbursement was studied in one US center and surgery, compared with endovascular treatment, was associated with longer hospitalization, but lower hospital costs, higher surgeon reimbursement, and similar hospital reimbursements (Hoh et al. 2009). It is easy for those who practice endovascular coiling to scare people about open surgery required for clipping. They may say that for clipping, the skull will be opened, the brain may get damaged, and therefore there are more chances of bad results, while endovascular treatment is safer as there is no open operation. The patient and family may not understand the importance of the experience of the surgeon or that sometimes something that sounds riskier is still the best for them. What they are told is that in coiling, the patient is being treated without a major brain operation. Is it ethical for those who practice coiling to focus mainly on the risks of clipping? On the other hand, how far is a surgeon who practices clipping justified in advocating clipping over coiling?

12.4.2.4 Radiosurgery Versus Surgery

The same ethical issues may apply regarding treatment by any radiosurgery modality, such as Gamma Knife, CyberKnife, etc. (Gottfried et al. 2004). The radiosurgery clinic neurosurgeon promises treatment without any immediate complications for a 1.3 cm vestibular schwannoma, while the operating neurosurgeon must always warn of the possibility of some complications of open surgery. Sometimes it can be very difficult to make patients and their relatives understand the balanced approach in any given situation.

12.4.2.5 Endoscopic Versus Conventional Microsurgery

Controversy exists over the benefits, efficacy, and safety of the endoscopic approach for complex skull base pathology over the microscopic approach, and endoscopy is becoming more widespread due to its obvious advantages (Mortini et al. 2003) and satisfaction for patients (Edem et al. 2013). In the absence of class I evidence to favor one method over the other, either method should be acceptable, and practitioners of one technique or the other must be mindful of not overemphasizing the negative aspects of the other method.

Pearl

Several factors affect how surgeons make decisions about treatment recommendations. They include surgeon comfort, surgeon bias, presence of class I evidence, existence of ongoing clinical trials, the impact of the surgeon’s training, and conflicts of interest (financial and others).

12.4.3 Factors Affecting Surgeons’ Decision-Making

12.4.3.1 Surgeon Comfort Level

There are many neurosurgeons who are not comfortable to operate on aneurysms, complex skull base tumors, complex spine surgery, and other conditions due to (1) their perceived level of expertise in various areas of neurosurgery, (2) the nature of their training, and (3) the nature of their hospital group in which subspecialization may be so developed that they focus on only one or maybe two areas of neurosurgery and there may be pressure to refer specialized cases to one’s partners.

12.4.3.2 Surgeon Bias

Surgeons are definitely subject to bias about what is the best treatment, and they may openly or inadvertently convey this bias to patients (Deekonda and Bernstein 2011). If a nonaneurysm expert feels coiling is generally safer than open microsurgery for an anterior communicating aneurysm, or a non-skull base surgeon feels that radiosurgery is safer than microsurgery for a 1.3 cm vestibular schwannoma, he/she may refer these patients for coiling or radiosurgery, respectively, by enumerating the high risks of surgery to the patients and extolling the advantages of the recommended approach. There is great asymmetry of power between surgeon and patient in that the surgeon is in control and authority and the patient is vulnerable. This gap is decreasing as patients become more informed about their disease, partly due to the internet, and more involved in their care. But in any given interaction, it is relatively easy for a surgeon to “sell” his/her preferred treatment option by the way he/she presents the information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree