Examination and Diagnosis of the Psychiatric Patient

5.1 Psychiatric Interview, History, and Mental Status Examination

5.1 Psychiatric Interview, History, and Mental Status Examination

The psychiatric interview is the most important element in the evaluation and care of persons with mental illness. A major purpose of the initial psychiatric interview is to obtain information that will establish a criteria-based diagnosis. This process, helpful in the prediction of the course of the illness and the prognosis, leads to treatment decisions. A well-conducted psychiatric interview results in a multidimensional understanding of the biopsychosocial elements of the disorder and provides the information necessary for the psychiatrist, in collaboration with the patient, to develop a person-centered treatment plan.

Equally important, the interview itself is often an essential part of the treatment process. From the very first moments of the encounter, the interview shapes the nature of the patient–physician relationship, which can have a profound influence on the outcome of treatment. The settings in which the psychiatric interview takes place include psychiatric inpatient units, medical nonpsychiatric inpatient units, emergency rooms, outpatient offices, nursing homes, other residential programs, and correctional facilities. The length of time for the interview, and its focus, will vary depending on the setting, the specific purpose of interview, and other factors (including concurrent competing demands for professional services).

Nevertheless, there are basic principles and techniques that are important for all psychiatric interviews, and these will be the focus of this section. There are special issues in the evaluation of children that will not be addressed. This section focuses on the psychiatric interview of adult patients.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Agreement as to Process

At the beginning of the interview the psychiatrist should introduce himself or herself and, depending on the circumstances, may need to identify why he or she is speaking with the patient. Unless implicit (the patient coming to the office), consent to proceed with the interview should be obtained and the nature of the interaction and the approximate (or specific) amount of time for the interview should be stated. The patient should be encouraged to identify any elements of the process that he or she wishes to alter or add.

A crucial issue is whether the patient is, directly or indirectly, seeking the evaluation on a voluntary basis or has been brought involuntarily for the assessment. This should be established before the interview begins, and this information will guide the interviewer especially in the early stages of the process.

Privacy and Confidentiality

Issues concerning confidentiality are crucial in the evaluation/treatment process and may need to be discussed on multiple occasions. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations must be carefully followed, and the appropriate paperwork must be presented to the patient.

Confidentiality is an essential component of the patient–doctor relationship. The interviewer should make every attempt to ensure that the content of the interview cannot be overheard by others. Sometimes, in a hospital unit or other institutional setting, this may be difficult. If the patient is sharing a room with others, an attempt should be made to use a different room for the interview. If this is not feasible, the interviewer may need to avoid certain topics or indicate that these issues can be discussed later when privacy can be ensured. Generally, at the beginning, the interviewer should indicate that the content of the session(s) will remain confidential except for what needs to be shared with the referring physician or treatment team. Some evaluations, including forensic and disability evaluations, are less confidential and what is discussed may be shared with others. In those cases, the interviewer should be explicit in stating that the session is not confidential and identify who will receive a report of the evaluation. This information should be carefully and fully documented in the patient’s record.

A special issue concerning confidentiality is when the patient indicates that he or she intends to harm another person. When the psychiatrist’s evaluation suggests that this might indeed happen, the psychiatrist may have a legal obligation to warn the potential victim. (The law concerning notification of a potential victim varies by state.) Psychiatrists should also consider their ethical obligations. Part of this obligation may be met by appropriate clinical measures such as increasing the dose of antipsychotic medication or hospitalizing the patient.

Often members of the patient’s family, including spouse, adult children, or parents, come with the patient to the first session or are present in the hospital or other institutional setting when the psychiatrist first sees the patient. If a family member wishes to talk to the psychiatrist, it is generally preferable to meet with the family member(s) and the patient together at the conclusion of the session and after the patient’s consent has been obtained. The psychiatrist should not bring up material the patient has shared but listen to the input from family members and discuss items that the patient introduces during the joint session. Occasionally, when family members have not asked to be seen, the psychiatrist may feel that including a family member or caregiver might be helpful and raise this subject with the patient. This may be the case when the patient is not able to communicate effectively. As always, the patient must give consent except if the psychiatrist determines that the patient is a danger to himself or herself or others. Sometimes family members might telephone the psychiatrist. Except in an emergency, consent should be obtained from the patient before the psychiatrist speaks to the relative. As indicated above, the psychiatrist should not bring up material that the patient has shared but listen to the input from the family member. The patient should be told when a family member has contacted the psychiatrist even if the patient has given consent for this to occur.

In educational and, occasionally, forensic settings, there may be occasions when the session is recorded. The patient must be fully informed about the recording and how the recording will be used. The length of time the recording will be kept and how access to it will be restricted must be discussed. Occasionally in educational settings, one-way mirrors may be used as a tool to allow trainees to benefit from the observation of an interview. The patient should be informed of the use of the one-way mirror and the category of the observers and be reassured that the observers are also bound by the rules of confidentiality. The patient’s consent for proceeding with the recording or use of the one-way mirror must be obtained, and it should be made clear that the patient’s receiving care will not be determined by whether he or she agrees to its use. These devices will have an impact on the interview that the psychiatrist should be open to discussing as the session unfolds.

Respect and Consideration

As should happen in all clinical settings, the patient must be treated with respect, and the interviewer should be considerate of the circumstances of the patient’s condition. The patient is often experiencing considerable pain or other distress and frequently is feeling vulnerable and uncertain of what may happen. Because of the stigma of mental illness and misconceptions about psychiatry, the patient may be especially concerned, or even frightened, about seeing a psychiatrist. The skilled psychiatrist is aware of these potential issues and interacts in a manner to decrease, or at least not increase, the distress. The success of the initial interview will often depend on the physician’s ability to allay excessive anxiety.

Rapport/Empathy

Respect for and consideration of the patient will contribute to the development of rapport. In the clinical setting, rapport can be defined as the harmonious responsiveness of the physician to the patient and the patient to the physician. It is important that patients increasingly feel that the evaluation is a joint effort and that the psychiatrist is truly interested in their story. Empathic interventions (“That must have been very difficult for you” or “I’m beginning to understand how awful that felt”) further increase the rapport. Frequently a nonverbal response (raised eyebrows or leaning toward the patient) or a very brief response (“Wow”) will be similarly effective. Empathy is understanding what the patient is thinking and feeling and it occurs when the psychiatrist is able to put himself or herself in the patient’s place while at the same time maintaining objectivity. For the psychiatrist to truly understand what the patient is thinking and feeling requires an appreciation of many issues in the patient’s life. As the interview progresses, the patient’s story unfolds and patterns of behaviors become evident, and it becomes clearer what the patient may actually have experienced. Early in the interview, the psychiatrist may not be as fully confident of where the patient is or was (although the patient’s nonverbal cues can be very helpful). If the psychiatrist is uncertain about the patient’s experience, it is often best not to guess but to encourage the patient to continue. Head nodding, putting down one’s pen, leaning toward the patient, or a brief comment, “I see,” can accomplish this objective and simultaneously indicate that this is important material. In fact the large majority of empathic responses in an interview are nonverbal.

An essential ingredient in empathy is retaining objectivity. Maintaining objectivity is crucial in a therapeutic relationship and it differentiates empathy from identification. With identification, psychiatrists not only understand the emotion but also experience it to the extent that they lose the ability to be objective. This blurring of boundaries between the patient and psychiatrist can be confusing and distressing to many patients, especially to those who as part of their illness already have significant boundary problems (e.g., individuals with borderline personality disorder). Identification can also be draining to the psychiatrist and lead to disengagement and ultimately burnout.

Patient–Physician Relationship

The patient–physician relationship is the core of the practice of medicine. (For many years the term used was “physician–patient” or “doctor–patient,” but the order is sometimes reversed to reinforce that the treatment should always be patient centered.) Although the relationship between any one patient and physician will vary depending on each of their personalities and past experiences as well as the setting and purpose of the encounter, there are general principles that, when followed, help to ensure that the relationship established is helpful.

The patient comes to the interview seeking help. Even in those instances when the patient comes on the insistence of others (i.e., spouse, family, courts), help may be sought by the patient in dealing with the person requesting or requiring the evaluation or treatment. This desire for help motivates the patient to share with a stranger information and feelings that are distressing, personal, and often private. The patient is willing, to various degrees, to do so because of a belief that the doctor has the expertise, by virtue of training and experience, to be of help. Right from the very first encounter (sometimes the initial phone call), the patient’s willingness to share is increased or decreased depending on the verbal and often the nonverbal interventions of the physician and other staff. As the physician’s behaviors demonstrate respect and consideration, rapport begins to develop. This is increased as the patient feels safe and comfortable. If the patient feels secure that what is said in the interview remains confidential, he or she will be more open to sharing.

The sharing is reinforced by the nonjudgmental attitude and behavior of the physician. The patient may have been exposed to considerable negative responses, actual or feared, to their symptoms or behaviors, including criticism, disdain, belittlement, anger, or violence. Being able to share thoughts and feelings with a nonjudgmental listener is generally a positive experience.

There are two additional essential ingredients in a helpful patient–physician relationship. One is the demonstration by physicians that they understand what the patient is stating and emoting. It is not enough that the physician understands what the patient is relating, thinking, and feeling; this understanding must be conveyed to the patient if it is to nurture the therapeutic relationship. The interview is not just an intellectual exercise to arrive at a supportable diagnosis. The other essential ingredient in a helpful patient–physician relationship is the recognition by the patient that the physician cares. As the patient becomes aware that the physician not only understand but also cares, trust increases and the therapeutic alliance becomes stronger.

The patient–physician relationship is reinforced by the genuineness of the physician. Being able to laugh in response to a humorous comment, admit a mistake, or apologize for an error that inconvenienced the patient (e.g., being late for or missing an appointment) strengthens the therapeutic alliance. It is also important to be flexible in the interview and responsive to patient initiatives. If the patient brings in an item, for example, a photo that he or she wants to show the psychiatrist, it is good to look at it, ask questions, and thank the patient for sharing it. Much can be learned about the family history and dynamics from such a seemingly sidebar moment. In addition, the therapeutic alliance is strengthened. The psychiatrist should be mindful of the reality that there are no irrelevant moments in the interview room.

At times patients will ask questions about the psychiatrist. A good rule of thumb is that questions about the physician’s qualifications and position should generally be answered directly (e.g., board certification, hospital privileges). On occasion, such a question might actually be a sarcastic comment (“Did you really go to medical school?”). In this case it would be better to address the issue that provoked the comment rather than respond concretely. There is no easy answer to the question of how the psychiatrist should respond to personal questions (“Are you married?,” “Do you have children?,” “Do you watch football?”). Advice on how to respond will vary depending on several issues, including the type of psychotherapy being used or considered, the context in which the question is asked, and the wishes of the psychiatrist. Often, especially if the patient is being, or might be, seen for insight-oriented psychotherapy, it is useful to explore why the question is being asked. The question about children may be precipitated by the patient wondering if the psychiatrist has had personal experience in raising children, or more generally does the psychiatrist have the skills and experience necessary to meet the patient’s needs. In this instance, part of the psychiatrist’s response may be that he or she has had considerable experiences in helping people deal with issues of parenting. For patients being seen for supportive psychotherapy or medication management, answering the question, especially if it is not very personal, such as “Do you watch football?,” is quite appropriate. A major reason for not answering personal questions directly is that the interview may become psychiatrist centered rather than patient centered.

Occasionally, again depending on the nature of the treatment, it can be helpful for the psychiatrist to share some personal information even if it is not asked directly by the patient. The purpose of the self-revelation should always be to strengthen the therapeutic alliance to be helpful to the patient. Personal information should not be shared to meet the psychiatrist’s needs.

Conscious/Unconscious

In order to understand more fully the patient–physician relationship, unconscious processes must be considered. The reality is that the majority of mental activity remains outside of conscious awareness. In the interview, unconscious processes may be suggested by tangential references to an issue, slips of the tongue or mannerisms of speech, what is not said or avoided, and other defense mechanisms. For example, phrases such as “to tell you the truth” or “to speak frankly” suggest that the speaker does not usually tell the truth or speak frankly. In the initial interview it is best to note such mannerisms or slips but not to explore them. It may or may not be helpful to pursue them in subsequent sessions. In the interview, transference and countertransference are very significant expressions of unconscious processes. Transference is the process of the patient unconsciously and inappropriately displacing onto individuals in his or her current life those patterns of behavior and emotional reactions that originated with significant figures from earlier in life, often childhood. In the clinical situation the displacement is onto the psychiatrist, who is often an authority figure or a parent surrogate. It is important that the psychiatrist recognizes that the transference may be driving the behaviors of the patient, and the interactions with the psychiatrist may be based on distortions that have their origins much earlier in life. The patient may be angry, hostile, demanding, or obsequious not because of the reality of the relationship with the psychiatrist but because of former relationships and patterns of behaviors. Failure to recognize this process can lead to the psychiatrist inappropriately reacting to the patient’s behavior as if it were a personal attack on the psychiatrist.

Similarly, countertransference is the process where the physician unconsciously displaces onto the patient patterns of behaviors or emotional reactions as if he or she were a significant figure from earlier in the physician’s life. Psychiatrists should be alert to signs of countertransference issues (missed appointment by the psychiatrist, boredom, or sleepiness in a session). Supervision or consultations can be helpful as can personal therapy in helping the psychiatrist recognize and deal with these issues.

Although the patient comes for help, there may be forces that impede the movement to health. Resistances are the processes, conscious or unconscious, that interfere with the therapeutic objectives of treatment. The patient is generally unaware of the impact of these feelings, thinking, or behaviors, which take many different forms including exaggerated emotional responses, intellectualization, generalization, missed appointments, or acting out behaviors. Resistance may be fueled by repression, which is an unconscious process that keeps issues or feelings out of awareness. Because of repression, patients may not be aware of the conflicts that may be central to their illness. In insight-oriented psychotherapy, interpretations are interventions that undo the process of repression and allow the unconscious thoughts and feelings to come to awareness so that they can be dealt with. As a result of these interventions, the primary gain of the symptom, the unconscious purpose that it serves, may become clear. In the initial session, interpretations are generally avoided. The psychiatrist should make note of potential areas for exploration in subsequent sessions.

Person-Centered and Disorder-Based Interviews

A psychiatric interview should be person (patient) centered. That is, the focus should be on understanding the patient and enabling the patient to tell his or her story. The individuality of the patient’s experience is a central theme, and the patient’s life history is elicited, subject to the constraints of time, the patient’s willingness to share some of this material, and the skill of the interviewer. Adolf Meyer’s “life-charts” were graphic representations of the material collected in this endeavor and were a core component of the “psychobiological” understanding of illness. The patient’s early life experiences, family, education, occupation(s), religious beliefs and practices, hobbies, talents, relationships, and losses are some of the areas that, in concert with genetic and biological variables, contribute to the development of the personality. An appreciation of these experiences and their impact on the person is necessary in forming an understanding of the patient. It is not only the history that should be person centered. It is especially important that the resulting treatment plan be based on the patient’s goals, not the psychiatrist’s. Numerous studies have demonstrated that often the patient’s goals for treatment (e.g., safe housing) are not the same as the psychiatrist’s (e.g., decrease in hallucinations). This dichotomy can often be traced to the interview where the focus was not sufficiently person centered but rather was exclusively or largely symptom based. Even when the interviewer specifically asks about the patient’s goals and aspirations, the patient, having been exposed on numerous occasions to what a professional is interested in hearing about, may attempt to focus on “acceptable” or “expected” goals rather than his or her own goals. The patient should be explicitly encouraged to identify his or her goals and aspirations in his or her own words.

Traditionally, medicine has focused on illness and deficits rather than strengths and assets. A person-centered approach focuses on strengths and assets as well as deficits. During the assessment, it is often helpful to ask the patient, “Tell me about some of the things you do best,” or, “What do you consider your greatest asset?” A more open-ended question, such as, “Tell me about yourself,” may elicit information that focuses more on either strengths or deficits depending on a number of factors including the patient’s mood and self-image.

Safety and Comfort

Both the patient and the interviewer must feel safe. This includes physical safety. On occasion, especially in hospital or emergency room settings, this may require that other staff be present or that the door to the room where the interview is conducted be left ajar. In emergency room settings, it is generally advisable for the interviewer to have a clear, unencumbered exit path. Patients, especially if psychotic or confused, may feel threatened and need to be reassured that they are safe and the staff will do everything possible to ensure their safety. Sometimes it is useful to explicitly state, and sometimes demonstrate, that there are sufficient staff to prevent a situation from spiraling out of control. For some, often psychotic patients who are fearful of losing control, this can be reassuring. The interview may need to be shortened or quickly terminated if the patient becomes more agitated and threatening. Once issues of safety have been assessed (and for many outpatients this may be accomplished within a few seconds), the interviewer should inquire about the patient’s comfort and continue to be alert to the patient’s comfort throughout the interview. A direct question may be helpful in not only making the patient feel more comfortable but also in enhancing the patient–doctor relationship. This might include, “Are you warm enough?” or “Is that chair comfortable for you?” As the interview progresses, if the patient desires tissues or water it should be provided.

Time and Number of Sessions

For an initial interview, 45 to 90 minutes is generally allotted. For inpatients on a medical unit or at times for patients who are confused, in considerable distress, or psychotic, the length of time that can be tolerated in one sitting may be 20 to 30 minutes or less. In those instances, a number of brief sessions may be necessary. Even for patients who can tolerate longer sessions, more than one session may be necessary to complete an evaluation. The clinician must accept the reality that the history obtained is never complete or fully accurate. An interview is dynamic and some aspects of the evaluation are ongoing, such as how a patient responds to exploration and consideration of new material that emerges. If the patient is coming for treatment, as the initial interview progresses, the psychiatrist makes decisions about what can be continued in subsequent sessions.

PROCESS OF THE INTERVIEW

Before the Interview

For outpatients, the first contact with the psychiatrist office is often a telephone call. It is important that whomever is receiving the call understands how to respond if the patient is acutely distressed, confused, or expresses suicidal or homicidal intent. If the receiver of the call is not a mental health professional, the call should be transferred to the psychiatrist or other mental health professional, if available. If not available, the caller should be directed to a psychiatric emergency center or an emergency hotline. The receiver of the call should obtain the name and phone number of the caller and offer to initiate the call to the hotline if that is preferred by the caller.

Most calls are not of such an urgent nature. The receptionist (or whomever receives the call) should obtain the information that setting has deemed relevant for the first contact. Although the requested information varies considerably, it generally includes the name, age, address and telephone number(s) of the patient, who referred the patient, the reason for the referral, and insurance information. The patient is given relevant information about the office including length of time for the initial session, fees, and whom to call if there are additional questions. In many practices the psychiatrist will call the patient to discuss the reason for the appointment and to determine if indeed an appointment appears warranted. The timing of the appointment should reflect the apparent urgency of the problem. Asking the patient to bring information about past psychiatric and medical treatments as well as a list of medications (or preferably the medications themselves) can be very helpful. Frequently a patient is referred to the psychiatrist or a psychiatric facility. If possible, reviewing records that precede the patient can be quite helpful. Some psychiatrists prefer not to read records prior to the initial interview so that their initial view of the patient’s problems will not be unduly influenced by prior evaluations. Whether or not records are reviewed, it is important that the reason for the referral be understood as clearly as possible. This is especially important for forensic evaluations where the reason for the referral and the question(s) posed will help to shape the evaluation. Often, especially in the outpatient setting, a patient is referred to the psychiatrist by a primary care physician or other health care provider. Although not always feasible, communicating with the referring professional prior to the evaluation can be very helpful. It is critical to determine whether the patient is referred for only an evaluation with the ongoing treatment to be provided by the primary care physician or mental health provider (e.g., social worker) or if the patient is being referred for evaluation and treatment by the psychiatrist.

If the patient is referred by the court, a lawyer, or some other non–treatment-oriented agency such as an insurance company, the goals of the interview may be different from diagnosis and treatment recommendations. These goals can include determination of disability, questions of competence or capacity, or determining, if possible, the cause or contributors of the psychiatric illness. In these special circumstances, the patient and clinician are not entering a treatment relationship, and often the usual rules of confidentiality do not apply. This limited confidentiality must be explicitly established with the patient and must include a discussion of who will be receiving the information gathered during the interview.

The Waiting Room

When the patient arrives for the initial appointment, he or she is often given forms to complete. These generally include demographic and insurance information. In addition, the patient receives information about the practice (including contact information for evenings and weekends) and HIPAA-mandated information that must be read and signed. Many practices also ask for a list of medications, the name and address of the primary care physician, and identification of major medical problems and allergies. Sometimes the patient is asked what his or her major reason is for coming to the office. Increasingly, some psychiatrists ask the patient to fill out a questionnaire or a rating scale that identifies major symptoms. Such scales include the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) or the Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology Self Report (QIDS-SR), which are scales of depressive symptoms based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Diseases (DSM).

The Interview Room

The interview room itself should be relatively soundproof. The decor should be pleasant and not distracting. If feasible, it is a good idea to give the patient the choice of a soft chair or a hard-back chair. Sometimes the choice of the chair or how the chair is chosen can reveal characteristics of the patient. Many psychiatrists suggest that the interviewer’s chair and the patient’s chair be of relatively equal height so that the interviewer does not tower over the patient (or vice versa). It is generally agreed that the patient and the psychiatrist should be seated approximately 4 to 6 feet apart. The psychiatrist should not be seated behind a desk. The psychiatrist should dress professionally and be well groomed. Distractions should be kept to a minimum. Unless there is an urgent matter, there should be no telephone or beeper interruptions during the interview. The patient should feel that the time has been set aside just for him or her and that for this designated time he or she is the exclusive focus of the psychiatrist’s attention.

Initiation of the Interview

The patient is greeted in the waiting room by the psychiatrist who, with a friendly face, introduces himself or herself, extends a hand, and, if the patient reciprocates, gives a firm handshake. If the patient does not extend his or her hand, it is probably best not to comment at that point but warmly indicate the way to the interview room. The refusal to shake hands is probably an important issue, and the psychiatrist can keep this in mind for a potential inquiry if it is not brought up subsequently by the patient. Upon entering the interview room, if the patient has a coat, the psychiatrist can offer to take the coat and hang it up. The psychiatrist then indicates where the patient can sit. A brief pause can be helpful as there may be something the patient wants to say immediately. If not, the psychiatrist can inquire if the patient prefers to be called Mr. Smith, Thomas, or Tom. If this question is not asked, it is best to use the last name as some patients will find it presumptive to be called by their first name especially if the interviewer is many years younger. These first few minutes of the encounter, even before the formal interview begins, can be crucial to the success of the interview and the development of a helpful patient–doctor relationship. The patient, who is often anxious, forms an initial impression of the psychiatrist and begins to make decisions as to how much can be shared with this doctor. Psychiatrists can convey interest and support by exhibiting a warm, friendly face and other nonverbal communications such as leaning forward in their chair. It is generally useful for the psychiatrist to indicate how much time is available for the interview. The patient may have some questions about what will happen during this time, confidentiality, and other issues, and these questions should be answered directly by the psychiatrist. The psychiatrist can then continue with an open-ended inquiry, “Why don’t we start by you telling me what has led to your being here,” or simply, “What has led to your being here?” Often the response to this question will establish whether or not the patient has been referred. When a referral has been made, it is important to elicit from the patient his or her understanding of why he or she has been referred. Not uncommonly, the patient may be uncertain as to why he or she has been referred or may even feel angry at the referrer, often a primary care physician.

Open-Ended Questions

As the patient responds to these initial questions, it is very important that the psychiatrist interacts in a manner that allows the patient to tell his or her story. This is the primary goal of the data collection part of the interview, to elicit the patient’s story of his or her health and illness. In order to accomplish this objective, open-ended questions are a necessity. Open-ended questions identify an area but provide minimal structure as to how to respond. A typical open-ended question is, “Tell me about your pain.” This is in contrast to closed-ended questions that provide much structure and narrow the field from which a response may be chosen. “Is your pain sharp?” The ultimate closed-ended question leads to a “yes” or “no” answer. In the initial portion of the interview questions should be primarily open ended. As the patient responds, the psychiatrist reinforces the patient continuing by nodding or other supportive interventions. As the patient continues to share his or her story about an aspect of his or her health or illness, the psychiatrist may ask some increasingly closed-ended questions to understand some of the specifics of the history. Then, when that area is understood, the psychiatrist may make a transition to another area again using open-ended questions and eventually closed-ended questions until that area is well described. Hence, the interview should not be a single funnel of open-ended questions in the beginning and closed-ended questions at the end of the interview but rather a series of funnels, each of which begins with open-ended questions.

ELEMENTS OF THE INITIAL PSYCHIATRIC INTERVIEW

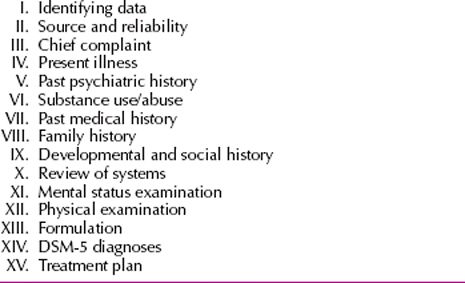

The interview is now well launched into the present illness. Table 5.1-1 lists the sections or parts of the initial psychiatric interview. Although not necessarily obtained during the interview in exactly this order, these are the categories that conventionally have been used to organize and record the elements of the evaluation.

Table 5.1-1

Table 5.1-1

Parts of the Initial Psychiatric Interview

The two overarching elements of the psychiatric interview are the patient history and the mental status examination. The patient history is based on the subjective report of the patient and in some cases the report of collaterals including other health care providers, family, and other caregivers. The mental status examination, on the other hand, is the interviewer’s objective tool similar to the physical examination in other areas of medicine. The physical examination, although not part of the interview itself, is included because of its potential relevance in the psychiatric diagnosis and also because it usually is included as part of the psychiatric evaluation especially in the inpatient setting. (In addition, much relevant information can be verbally obtained by the physician as parts of the physical examination are performed.) Similarly, the formulation, diagnosis, and treatment plan are included because they are products of the interview and also influence the course of the interview in a dynamic fashion as the interview moves back and forth pursuing, for example, whether certain diagnostic criteria are met or whether potential elements of the treatment plan are realistic. Details of the psychiatric interview are discussed below.

I. Identifying Data

This section is brief, one or two sentences, and typically includes the patient’s name, age, sex, marital status (or significant other relationship), race or ethnicity, and occupation. Often the referral source is also included.

II. Source and Reliability

It is important to clarify where the information has come from, especially if others have provided information or records reviewed, and the interviewer’s assessment of how reliable the data are.

III. Chief Complaint

This should be the patient’s presenting complaint, ideally in his or her own words. Examples include, “I’m depressed” or “I have a lot of anxiety.”

A 64-year-old man presented in a psychiatric emergency room with a chief complaint, “I’m melting away like a snowball.” He had become increasingly depressed over 3 months. Four weeks before the emergency room visit, he had seen his primary care physician who had increased his antidepressant medication (imipramine) from 25 to 75 mg and also added hydrochlorothiazide (50 mg) because of mild hypertension and slight pedal edema. Over the ensuing 4 weeks, the patient’s condition deteriorated. In the emergency room he was noted to have depressed mood, hopelessness, weakness, significant weight loss, and psychomotor retardation and was described as appearing “depleted.” He also appeared dehydrated, and blood work indicated he was hypokalemic. Examination of his medication revealed that the medication bottles had been mislabeled; he was taking 25 mg of imipramine (generally a nontherapeutic dose) and 150 mg of hydrochlorothiazide. He was indeed, “melting away like a snowball.” Fluid and potassium replacement and a therapeutic dose of an antidepressant resulted in significant improvement.

IV. History of Present Illness

The present illness is a chronological description of the evolution of the symptoms of the current episode. In addition, the account should also include any other changes that have occurred during this same time period in the patient’s interests, interpersonal relationships, behaviors, personal habits, and physical health. As noted above, the patient may provide much of the essential information for this section in response to an open-ended question such as, “Can you tell me in your own words what brings you here today?” Other times the clinician may have to lead the patient through parts of the presenting problem. Details that should be gathered include the length of time that the current symptoms have been present and whether there have been fluctuations in the nature or severity of those symptoms over time. (“I have been depressed for the past two weeks” vs. “I’ve had depression all my life”). The presence or absence of stressors should be established, and these may include situations at home, work, school, legal issues, medical comorbidities, and interpersonal difficulties. Also important are factors that alleviate or exacerbate symptoms such as medications, support, coping skills, or time of day. The essential questions to be answered in the history of the present illness include what (symptoms), how much (severity), how long, and associated factors. It is also important to identify why the patient is seeking help now and what are the “triggering” factors (“I’m here now because my girlfriend told me if I don’t get help with this nervousness she is going to leave me.”). Identifying the setting in which the illness began can be revealing and helpful in understanding the etiology of, or significant contributors to, the condition. If any treatment has been received for the current episode, it should be defined in terms of who saw the patient and how often, what was done (e.g., psychotherapy or medication), and the specifics of the modality used. Also, is that treatment continuing and, if not, why not? The psychiatrist should be alert for any hints of abuse by former therapists as this experience, unless addressed, can be a major impediment to a healthy and helpful therapeutic alliance.

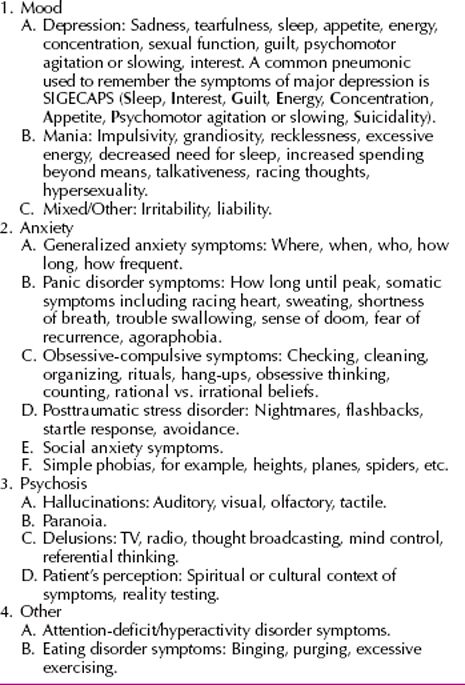

Often it can be helpful to include a psychiatric review of systems in conjunction with the history of the present illness to help rule in or out psychiatric diagnoses with pertinent positives and negatives. This may help to identify whether there are comorbid disorders or disorders that are actually more bothersome to the patient but are not initially identified for a variety of reasons. This review can be split into four major categories of mood, anxiety, psychosis, and other (Table 5.1-2). The clinician will want to ensure that these areas are covered in the comprehensive psychiatric interview.

Table 5.1-2

Table 5.1-2

Psychiatric Review of Systems

V. Past Psychiatric History

In the past psychiatric history, the clinician should obtain information about all psychiatric illnesses and their course over the patient’s lifetime, including symptoms and treatment. Because comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception, in addition to prior episodes of the same illness (e.g., past episodes of depression in an individual who has a major depressive disorder), the psychiatrist should also be alert for the signs and symptoms of other psychiatric disorders. Description of past symptoms should include when they occurred, how long they lasted, and the frequency and severity of episodes.

Past treatment episodes should be reviewed in detail. These include outpatient treatment such as psychotherapy (individual, group, couple, or family), day treatment or partial hospitalization, inpatient treatment, including voluntary or involuntary and what precipitated the need for the higher level of care, support groups, or other forms of treatment such as vocational training. Medications and other modalities such as electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy, or alternative treatments should be carefully reviewed. One should explore what was tried (may have to offer lists of names to patients), how long and at what doses they were used (to establish adequacy of the trials), and why they were stopped. Important questions include what was the response to the medication or modality and whether there were side effects. It is also helpful to establish whether there was reasonable compliance with the recommended treatment. The psychiatrist should also inquire whether a diagnosis was made, what it was, and who made the diagnosis. Although a diagnosis made by another clinician should not be automatically accepted as valid, it is important information that can be used by the psychiatrist in forming his or her opinion.

Special consideration should be given to establishing a lethality history that is important in the assessment of current risk. Past suicidal ideation, intent, plan, and attempts should be reviewed including the nature of attempts, perceived lethality of the attempts, save potential, suicide notes, giving away things, or other death preparations. Violence and homicidality history will include any violent actions or intent. Specific questions about domestic violence, legal complications, and outcome of the victim may be helpful in defining this history more clearly. History of nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior should also be covered including any history of cutting, burning, banging head, and biting oneself. The feelings, including relief of distress, that accompany or follow the behavior should also be explored as well as the degree to which the patient has gone to hide the evidence of these behaviors.

VI. Substance Use, Abuse, and Addictions

A careful review of substance use, abuse, and addictions is essential to the psychiatric interview. The clinician should keep in mind that this information may be difficult for the patient to discuss, and a nonjudgmental style will elicit more accurate information. If the patient seems reluctant to share such information specific questions may be helpful (e.g., “Have you ever used marijuana?” or “Do you typically drink alcohol every day?”). History of use should include which substances have been used, including alcohol, drugs, medications (prescribed or not prescribed to the patient), and routes of use (oral, snorting, or intravenous). The frequency and amount of use should be determined, keeping in mind the tendency for patients to minimize or deny use that may be perceived as socially unacceptable. Also, there are many misconceptions about alcohol that can lead to erroneous data. The definition of alcohol may be misunderstood, for example, “No, I don’t use alcohol,” yet later in the same interview, “I drink a fair amount of beer.” Also the amount of alcohol can be confused with the volume of the drink: “I’m not worried about my alcohol use. I mix my own drinks and I add a lot of water.” in response to a follow-up question, “How much bourbon? Probably three or four shots?” Tolerance, the need for increasing amounts of use, and any withdrawal symptoms should be established to help determine abuse versus dependence. Impact of use on social interactions, work, school, legal consequences, and driving while intoxicated (DWI) should be covered. Some psychiatrists use a brief standardized questionnaire, the CAGE or RAPS4, to identify alcohol abuse or dependence.

CAGE includes four questions: Have you ever Cut down on your drinking? Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? Have you ever felt bad or Guilty about your drinking? Have you ever had a drink the first thing in the morning, as an Eye-opener, to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover? The Rapid Alcohol Problem Screen 4 (RAPS4) also consists of four questions: Have you ever felt guilty after drinking (Remorse), could not remember things said or did after drinking (Amnesia), failed to do what was normally expected after drinking (Perform), or had a morning drink (Starter)?

Any periods of sobriety should be noted including length of time and setting such as in jail, legally mandated, and so forth. A history of treatment episodes should be explored, including inpatient detoxification or rehabilitation, outpatient treatment, group therapy, or other settings including self-help groups, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA), halfway houses, or group homes.

Current substance abuse or dependence can have a significant impact on psychiatric symptoms and treatment course. The patient’s readiness for change should be determined including whether they are in the precontemplative, contemplative, or action phase. Referral to the appropriate treatment setting should be considered.

Other important substances and addictions that should be covered in this section include tobacco and caffeine use, gambling, eating behaviors, and Internet use. Exploration of tobacco use is especially important because persons abusing substances are more likely to die as a result of tobacco use than because of the identified abused substance. Gambling history should include casino visits, horse racing, lottery and scratch cards, and sports betting. Addictive type eating may include binge eating disorder. Overeaters Anonymous (OA) and Gamblers Anonymous (GA) are 12-step programs, similar to AA, for patients with addictive eating behaviors and gambling addictions.

VII. Past Medical History

The past medical history includes an account of major medical illnesses and conditions as well as treatments, both past and present. Any past surgeries should be also reviewed. It is important to understand the patient’s reaction to these illnesses and the coping skills employed. The past medical history is an important consideration when determining potential causes of mental illness as well as comorbid or confounding factors and may dictate potential treatment options or limitations. Medical illnesses can precipitate a psychiatric disorder (e.g., anxiety disorder in an individual recently diagnosed with cancer), mimic a psychiatric disorder (hyperthyroidism resembling an anxiety disorder), be precipitated by a psychiatric disorder or its treatment (metabolic syndrome in a patient on a second-generation antipsychotic medication), or influence the choice of treatment of a psychiatric disorder (renal disorder and the use of lithium carbonate). It is important to pay special attention to neurological issues including seizures, head injury, and pain disorder. Any known history of prenatal or birthing problems or issues with developmental milestones should be noted. In women, a reproductive and menstrual history is important as well as a careful assessment of potential for current or future pregnancy. (“How do you know you are not pregnant?” may be answered with “Because I have had my tubes tied” or “I just hope I’m not.”)

A careful review of all current medications is very important. This should include all current psychiatric medications with attention to how long they have been used, compliance with schedules, effect of the medications, and any side effects. It is often helpful to be very specific in determining compliance and side effects including asking questions such as, “How many days of the week are you able to actually take this medication?” or “Have you noticed any change in your sexual function since starting this medication?,” as the patient may not spontaneously offer this information, which may be embarrassing or perceived to be treatment interfering.

Nonpsychiatric medications, over-the-counter medications, sleep aids, herbal, and alternative medications should also be reviewed. These can all potentially have psychiatric implications including side effects or produce symptoms as well as potential medication interactions dictating treatment options. Optimally the patient should be asked to bring all medications currently being taken, prescribed or not, over-the-counter preparations, vitamins, and herbs to the interview.

Allergies to medications must be covered, including which medication and the nature of, the extent of, and the treatment of the allergic response. Psychiatric patients should be encouraged to have adequate and regular medical care. The sharing of appropriate information among the primary care physicians, other medical specialists, and the psychiatrist can be very helpful for optimal patient care. The initial interview is an opportunity to reinforce that concept with the patient. At times a patient may not want information to be shared with his or her primary care physician. This wish should be respected, although it may be useful to explore if there is some information that can be shared. Often patients want to restrict certain social or family information (e.g., an extramarital affair) but are comfortable with other information (medication prescribed) being shared.

VIII. Family History

Because many psychiatric illnesses are familial and a significant number of those have a genetic predisposition, if not cause, a careful review of family history is an essential part of the psychiatric assessment. Furthermore, an accurate family history helps not only in defining a patient’s potential risk factors for specific illnesses but also the formative psychosocial background of the patient. Psychiatric diagnoses, medications, hospitalizations, substance use disorders, and lethality history should all be covered. The importance of these issues is highlighted, for example, by the evidence that, at times, there appears to be a familial response to medications, and a family history of suicide is a significant risk factor for suicidal behaviors in the patient. The interviewer must keep in mind that the diagnosis ascribed to a family member may or may not be accurate and some data about the presentation and treatment of that illness may be helpful. Medical illnesses present in family histories may also be important in both the diagnosis and the treatment of the patient. An example is a family history of diabetes or hyperlipidemia affecting the choice of antipsychotic medication that may carry a risk for development of these illnesses in the patient. Family traditions, beliefs, and expectations may also play a significant role in the development, expression, or course of the illness. Also the family history is important in identifying potential support as well as stresses for the patient and, depending on the degree of disability of the patient, the availability and adequacy of potential caregivers.

IX. Developmental and Social History

The developmental and social history reviews the stages of the patient’s life. It is an important tool in determining the context of psychiatric symptoms and illnesses and may, in fact, identify some of the major factors in the evolution of the disorder. Frequently, current psychosocial stressors will be revealed in the course of obtaining a social history. It can often be helpful to review the social history chronologically to ensure all information is covered.

Any available information concerning prenatal or birthing history and developmental milestones should be noted. For the large majority of adult patients, such information is not readily available and when it is it may not be fully accurate. Childhood history will include childhood home environment including members of the family and social environment including the number and quality of friendships. A detailed school history including how far the patient went in school and how old he or she was at that level, any special education circumstances or learning disorders, behavioral problems at school, academic performance, and extracurricular activities should be obtained. Childhood physical and sexual abuse should be carefully queried.

Work history will include types of jobs, performance at jobs, reasons for changing jobs, and current work status. The nature of the patient’s relationships with supervisors and coworkers should be reviewed. The patient’s income, financial issues, and insurance coverage including pharmacy benefits are often important issues.

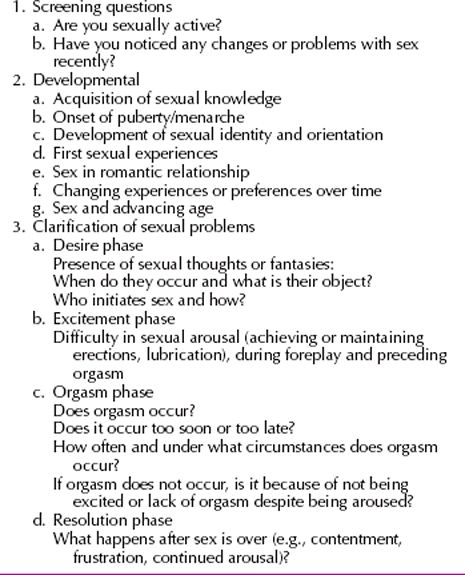

Military history, where applicable, should be noted including rank achieved, combat exposure, disciplinary actions, and discharge status. Marriage and relationship history, including sexual preferences and current family structure, should be explored. This should include the patient’s capacity to develop and maintain stable and mutually satisfying relationships as well as issues of intimacy and sexual behaviors. Current relationships with parents, grandparents, children, and grandchildren are an important part of the social history. Legal history is also relevant, especially any pending charges or lawsuits. The social history also includes hobbies, interests, pets, and leisure time activities and how this has fluctuated over time. It is important to identify cultural and religious influences on the patient’s life and current religious beliefs and practices. A brief overview of the sexual history is given in Table 5.1-3.

Table 5.1-3

Table 5.1-3

Sexual History

X. Review of Systems

The review of systems attempts to capture any current physical or psychological signs and symptoms not already identified in the present illness. Particular attention is paid to neurological and systemic symptoms (e.g., fatigue or weakness). Illnesses that might contribute to the presenting complaints or influence the choice of therapeutic agents should be carefully considered (e.g., endocrine, hepatic, or renal disorders). Generally, the review of systems is organized by the major systems of the body.

XI. Mental Status Examination

The mental status examination (MSE) is the psychiatric equivalent of the physical examination in the rest of medicine. The MSE explores all the areas of mental functioning and denotes evidence of signs and symptoms of mental illnesses. Data are gathered for the mental status examination throughout the interview from the initial moments of the interaction, including what the patient is wearing and their general presentation. Most of the information does not require direct questioning, and the information gathered from observation may give the clinician a different dataset than patient responses. Direct questioning augments and rounds out the MSE. The MSE gives the clinician a snapshot of the patient’s mental status at the time of the interview and is useful for subsequent visits to compare and monitor changes over time. The psychiatric MSE includes cognitive screening most often in the form of the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE), but the MMSE is not to be confused with the MSE overall. The components of the MSE are presented in this section in the order one might include them in the written note for organizational purposes, but as noted above, the data are gathered throughout the interview.

Appearance and Behavior. This section consists of a general description of how the patient looks and acts during the interview. Does the patient appear to be his or her stated age, younger or older? Is this related to the patient’s style of dress, physical features, or style of interaction? Items to be noted include what the patient is wearing, including body jewelry, and whether it is appropriate for the context. For example, a patient in a hospital gown would be appropriate in the emergency room or inpatient unit but not in an outpatient clinic. Distinguishing features, including disfigurations, scars, and tattoos, are noted. Grooming and hygiene also are included in the overall appearance and can be clues to the patient’s level of functioning.

The description of a patient’s behavior includes a general statement about whether he or she is exhibiting acute distress and then a more specific statement about the patient’s approach to the interview. The patient may be described as cooperative, agitated, disinhibited, disinterested, and so forth. Once again, appropriateness is an important factor to consider in the interpretation of the observation. If a patient is brought involuntarily for examination, it may be appropriate, certainly understandable, that he or she is somewhat uncooperative, especially at the beginning of the interview.

Motor Activity. Motor activity may be described as normal, slowed (bradykinesia), or agitated (hyperkinesia). This can give clues to diagnoses (e.g., depression vs. mania) as well as confounding neurological or medical issues. Gait, freedom of movement, any unusual or sustained postures, pacing, and hand wringing are described. The presence or absence of any tics should be noted, as should be jitteriness, tremor, apparent restlessness, lip-smacking, and tongue protrusions. These can be clues to adverse reactions or side effects of medications such as tardive dyskinesia, akathisia, or parkinsonian features from antipsychotic medications or suggestion of symptoms of illnesses such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Speech. Evaluation of speech is an important part of the MSE. Elements considered include fluency, amount, rate, tone, and volume. Fluency can refer to whether the patient has full command of the English language as well as potentially more subtle fluency issues such as stuttering, word finding difficulties, or paraphasic errors. (A Spanish-speaking patient with an interpreter would be considered not fluent in English, but an attempt should be made to establish whether he or she is fluent in Spanish.) The evaluation of the amount of speech refers to whether it is normal, increased, or decreased. Decreased amounts of speech may suggest several different things ranging from anxiety or disinterest to thought blocking or psychosis. Increased amounts of speech often (but not always) are suggestive of mania or hypomania. A related element is the speed or rate of speech. Is it slowed or rapid (pressured)? Finally, speech can be evaluated for its tone and volume. Descriptive terms for these elements include irritable, anxious, dysphoric, loud, quiet, timid, angry, or childlike.

Mood. The terms mood and affect

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree