The Evidential Basis of CBT for Addiction

CBT has brought key mechanisms of addiction into much sharper focus. This has allowed for the development of more precise therapeutic interventions that target aspects of the dynamic interaction between person, situation and appetitive impulse. The present text is a consolidation or evolution of CBT theory and practice. One of the strengths of CBT approach is its capacity to accommodate innovations. The formulation-based approach is crucial in this regard, as it enables the deployment of novel techniques to target psychological processes. The development of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), for example, illustrates this ethos. Mindfulness-based meditation comes from a very different tradition to that of CBT but has demonstrably brought added value to certain clinical populations such as those with chronic depression and high propensity to relapse (Segal et al., 2002). As yet, mindfulness protocols have rarely been subjected to the rigours of controlled clinical trials with addicted populations. An exception to this is a single-site randomized controlled trial of mindfulness training for people trying to give up smoking. Brewer et al. (2011) found a greater point prevalence abstinence rate at the end of 17-week follow-up (31% versus 6%, p = 0.012) among a group of smokers were taught mindfulness compared with those who received a standard package of care.

Meta-analytic Findings

First, consider the findings of clinical trials reflected in meta-analytic studies. Dutra et al. (2008), for example, found cognitive behavioural therapy alone and relapse prevention produced low to moderate effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.28 and 0.32) respectively. This contrasts unfavourably with median effect sizes of d = 0.8 and 0.9 observed with panic disorder and generalized disorder respectively, although an effect size of 0.3 was noted with depression (Westen and Morrison, 2001), based on data from 34 studies. This rather mixed message receives support from an earlier review. Irwin et al. (1999) found in their meta-analysis of 26 comparative treatment studies involving 9504 participants that the overall treatment effect of group-based relapse-prevention interventions for substance misuse was indeed small (r = 0.14), but statistically reliable. This modest figure reflects the relatively greater response on the part of individuals recruited to studies investigating alcohol dependence but disguises the negligible effect size noted with, for example, cocaine or nicotine addiction. However, the effect of relapse prevention on improving overall psychosocial adjustment was significantly larger (r = 0.48).

Behavioural Approaches

Specific behavioural techniques such as contingency management, based on operant conditioning, appear to deliver greater effect sizes than observed with broader CBT approaches. Variants of this approach include Behavioural Couples Therapy (O’Farrell and Fals-Stewart, 2006) and Social Behaviour Network Therapy (Copello et al., 2006). They share an emphasis on reinforcing abstinence or adherence to the treatment goal by using either social or monetary reinforcements or combination of both. Clearly, these exemplify effective behaviour modification. From a cognitive control perspective, behavioural approaches that alter contingencies also directly influence the contents of working memory. The systematic and repetitious nature of reinforcement approaches is in effect a form of rehearsal or goal maintenance. From the model depicted in Figure 2.2, it is clear that whatever occupies the ‘high ground’ of working memory or executive control can exert influence over the surrounding cognitive terrain. Hypothetically, the maintenance and rehearsal of a clear behavioural goal should influence top-down processes such as the allocation of attentional resources. Moreover, by occupying a system that has limited capacity, these recovery orientated goals can reduce the likelihood of the working memory system defaulting to appetitive goals. These variants are limited to some extent, because they require the active participation of a non-substance-misusing partner or the cooperation of others in the addicted person’s social network. A recent review of treatments using contingency management alone (Prendergast et al., 2006) indicated moderate–high effect sizes (d = 0.42). Contingency management appeared more effective in treating opiate use (d = 0.65) and cocaine use (d = 0.66) compared with tobacco (d = 0.31) or polydrug misuse (d = 0.42).

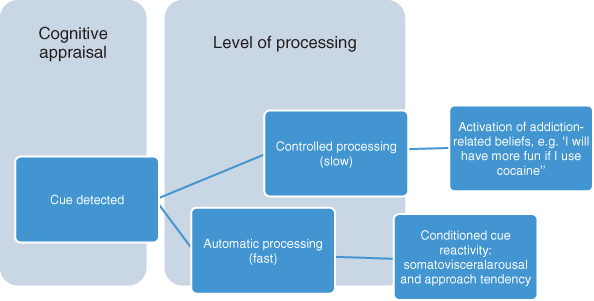

Figure 2.2 Two routes to addictive behaviour: a fast route triggered by preferential detection of potential drug cues; a slow route reliant on reflective or conscious deliberation.

Calibrating and comparing effect sizes calculated using different statistical analyses has its limitations. The data quoted here nonetheless illustrate that treatment effect sizes tend to be smaller and more varied with addictive disorders than with emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression. These meta-analytic findings appear to be telling us two things about responding therapeutically to addiction and coexisting mental health problems. On a positive note, we can advise our clients with concomitant panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder that treatment can be very effective, and people with depression will also benefit to a significant degree. This will contribute to overcoming addictive impulses insofar as negative affect can be a powerful motivator. Second, and perhaps less positively, we would have to inform our clients that their addictive behaviour might prove more resistant to treatment, and will therefore require more intervention, probably over a longer timeframe. An important exception to this is that contingency management can change addictive behaviour, at least in the short term. Overall, however, this pattern of results suggests key mechanisms of change are being overlooked in conventional cognitive therapy applications.

Diverse Treatments Mostly Deliver Equivalent Outcomes

Findings from clinical outcome studies indicate that different treatment approaches tend to produce similar outcomes. This presents a particular challenge to cognitive behavioural approaches, given the focus on particular mechanisms of change. In the USA, Project MATCH (Project MATCH Research Group, 1997) compared CBT, Twelve-Step facilitation and motivational enhancement therapy in a multisite controlled trial. Hypothesized treatment matching effects were largely absent, but most participants showed a significant reduction in the frequency and intensity of alcohol consumption. The COMBINE (combined pharmacotherapies and behavioural interventions for alcohol dependence) study (Anton et al., 2006), another large multi-site trial, evaluated the relative efficacy of various combinations of pharmacotherapy, behavioural approaches and medical management conditions Again, all participants showed largely equivalent therapeutic gain as indexed by reduced alcohol consumption. This included those receiving the brief but focused medical management condition. Similarly, in the UK, the UKATT (2005) alcohol treatment trial compared motivational enhancement therapy and Social Behavioural Network Therapy and found both equally effective: both groups, totalling 742, showed substantial, but equivalent, decreases of 44 per cent in alcohol consumption when followed up after 12 months.

What Are the Mechanisms of Change?

So far, so good: CBT at least seems to work as well as other approaches. But further results from controlled clinical trials evaluating CBT raise fundamental questions about efficacy. In a controlled study of cocaine dependence (Crits-Christoph et al., 1999), both cognitive therapy and brief psychodynamic therapy led to significantly poorer outcomes indexed by rates of abstinence compared with traditional Twelve-Step counselling delivered to a combination of individual and group-based interventions. This was despite the fact that the Twelve-Step clients attended significantly fewer sessions. A further challenge to the emphasis on coping skills that is central to CBT emerges from a study by Litt et al. (2003). These researchers assigned 128 alcohol-dependent men and women to 26 weeks of group therapy consisting of either CBT aimed at developing coping skills or interactional therapy intended to examine interpersonal relationships. Both treatments yielded good reduced drinking outcomes throughout the 18-month follow-up period. Moreover, increased coping skills was a significant predictor of outcome but neither treatment was superior in this regard.

Partly in response to the findings of equivalent outcome with diverse interventions, Orford (2008) challenged addiction treatment researchers to focus on empirically supported common change processes. But what could these processes be? What is the common currency across such diverse terrain as Twelve-Step facilitation, motivational enhancement, CBT, behaviour and social network therapy, pharmacotherapy and structured advice sessions from a medical practitioner? Litt et al. (2003) considered non-specific treatment effects, suggesting, for example, that suitably motivated treatment seekers were in a position to capitalize on the opportunities for learning afforded by any structured treatment. Orford (2008a, p. 707) considered broader contextual factors to be plausible candidates:

Such a model emphasises factors such as client commitment, therapist allegiance and the client–therapist alliance, and views personal change as being embedded within a complex, multi-component treatment system, itself nested within a broader life system that contains an array of inter-related factors promoting or constraining positive change.

This does not account for the fact that relatively straightforward behavioural techniques such as contingency management appear to deliver robust gains, although these fade with the contingency. More importantly, invoking a role for non-specific factors brings us no closer to understanding, let alone modifying, the mechanisms that account for the tenacity of addiction.

The Missing Variable?

The proposal that overcoming addiction entails an essentially cognitive conflict suggests that the extent to which therapeutic interventions can enhance cognitive control will index their therapeutic potency. This remains hypothetical, but is at least consistent with the finding that contingency management, CBT, Twelve-Step approaches, substance-focused counselling and motivational interviewing have been shown to be equally effective (or in many cases rather less than effective) in addressing addictive disorders. This points to the existence of a common factor or component process, which contrives to sustain self-control across a range of situations, in both the long term and short term. This is my candidate for ‘the missing variable’ that has eluded and baffled many clinical investigators. In fairness, this could be because cognitive control is a multifaceted variable. I propose that the extent to which diverse treatments foster and sustain an increased level of cognitive control will have a direct bearing on the efficacy. There is a hint of circularity in this proposition – good outcomes in addiction are de facto evidence of robust cognitive control – until it is established what are the components processes of cognitive control and how can these can be more deliberately accentuated in a therapeutic framework. As will hopefully become apparent in this text, the components of cognitive control are indeed becoming more clearly specified, and being translated into promising therapeutic strategies. Without the development of dual-representation theories, positing qualitatively different types of information processing, none of this would have been possible.

A Dual-Processing Framework

Strack and Deutsch (2004) have outlined a theoretical framework termed the Reflective Impulsive Model (RIM) that describes a two-systems model to account for aspects of human behaviour. In a subsequent article (Deutsch and Strack, 2006), they explored the implications of their model for addictive behaviour. The basic assumption of the model is that behaviour results from the operation of two distinct cognitive processing systems. These are a reflective system that is deliberate, intentional and decisive, and parallel but sometimes in opposition to this, an impulsive system. The latter is typically fast, effortless and implicit or intuitive. The RIM is one of several theoretical frameworks that shares a dual-processing architecture derived from earlier work by, for example, Shiffrin and Schneider (1977). The defining feature of these models is the recognition that information can be processed by two qualitatively distinct modes, controlled and automatic, corresponding to the reflective and impulsive systems. Once automatic processes are established, they acquire autonomy from controlled processes. In normal operation they are essentially capacity free, in marked contrast to the ‘bottleneck’ that constrains controlled processing.

Automatic processes are always ‘switched on’ and can interrupt or draw attention away from deliberate or controlled processes. One outcome of this is that the reflective system, where information is processed explicitly or rule based, is more prone to distraction or diversion. An apt example would be an individual trying to abstain from alcohol travelling to work. Here, controlled processing would be required to complete the journey and keep in mind the priorities and tasks that need to be addressed on arrival. There is now abundant evidence that individuals in this scenario would find their attention captured by stimuli associated with alcohol such as adverts, bars or retail outlets where alcohol is for sale. The essential point is that this attentional capture takes place regardless of the individual’s decision to ignore such cues. Further, as will be seen in Chapter 7, once these cues have captured attention addicted individuals have difficulty in disengaging from this.

Bechara et al. (2006) described a neural architecture that provides a plausible basis for two cognitive systems, operating in parallel but sometimes in conflict as in the case of addiction. These theorists refer to an ‘impulsive amygdala-dependent’ system that signals pain or pleasure associated with immediate or short term outcomes that contrasts with a ‘reflective prefrontal-dependent’ neural system responsible for signalling future pain or pleasure (Bechara et al., 2006, p. 216). Both of these theoretical accounts, speaking to cognitive and neural systems respectively, posit a competitive process that precedes behavioural expression. In many scenarios, impulsive or short-term imperatives are easily reconciled with long-term objectives. A well-motivated but nonetheless hungry worker, for example, will diligently complete a tedious task before lunch. In this scenario, the individual appears able to choose an outcome that accommodates a range of motives and needs.

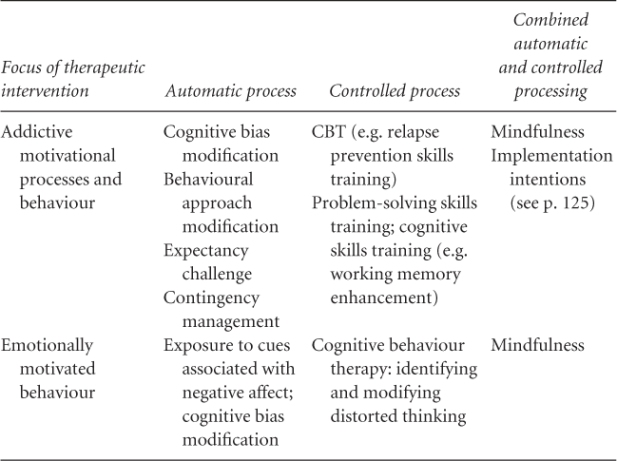

Bechara and colleagues propose that in the context of addiction there is a lack of equilibrium between the impulsive and reflective neural systems. Specifically, drawing on incentive models of addiction (e.g. Berridge and Robinson, 1995), they speculated that the sensitized impulsive system becomes more influential and more difficult for the reflective system to override. Moreover, the capacity to inhibit pre-potent responses is also compromised in individuals who have developed substance dependence (Noel et al., 2003), analogous to that observed in patients with ventromedial prefrontal lesions. Overall, dual-representation theories present major challenges to extant therapeutic approaches but also offer opportunities for the development of innovative cognitive and behavioural remedies. Table 2.1 shows how models where information is processed at different levels can accommodate different therapeutic procedures in response to both addictive behaviour and behaviour linked with negative emotional states, in keeping with the CHANGE framework. In reality, both automatic and controlled processes act in concert, as component processes can at least be partially differentiated as in the table. Implementation intentions, for instance (see p. 125) aim to recruit both automatic and controlled processes, by instigating rehearsal and activation of coping skills in response to cues. As will be seen (Chapter 4, pp. 58–59), what is encoded in working memory as a conscious goal can nonetheless influence attentional processing and behavioural activation automatically, and hence require little or no effort once the goal remains encoded.

Table 2.1 Dual processes mapped onto therapeutic interventions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree