Fig. 11.1

Surgical staging system for primary spinal tumours according to Weinstein, Boriani and Biagini (WBB). The spinal column and its surrounding soft tissue, the spinal canal with the thecal sac and its contents are divided into 12 zones and 5 lettered compartments from outside the spine to the spinal canal: extraosseous paraspinal soft tissue compartment (A), superficial intraosseous compartment (B), deep intraosseous compartment (C), epidural compartment (D), intradural compartment (E)

11.2.1.6 Outcome

The outcome of primary spinal tumours largely depends on the histology and the extent of tumour resection. Incomplete resection of primary tumours or violation of tumour margins carries a high risk for local tumour recurrence and determines ultimately the survival of the patients. Survival of patients with primary spine tumours decreases dramatically in the case of a tumour recurrence. The best results are obtained with “en bloc resection techniques” with tumour-free margins. Therefore a complete en bloc resection of the tumour should be carried out whenever technically feasible.

11.2.2 Vertebral Hemangioma

Vertebral hemangiomas are the most common benign tumours of the spine and account for approximately 2–3 % of all spine tumours. From larger autopsy studies the incidence is reported to be 10–12 %; however vertebral hemangiomas are usually asymptomatic and usually diagnosed incidentally. The peak incidence is the fourth to sixth decade. Vertebral hemangiomas are extremely vascularized slowly growing tumours histologically composed of irregular vascular space collections surrounded by endothelial cells. On MRI, vertebral hemangiomas appear as T1 and T2 hyperintense lesions within the vertebral body. Symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas are usually treated conservatively. Further treatment options are vertebroplasty and embolization. In very rare cases vertebral hemangiomas cause instability and spinal cord compression (Fig. 11.2a–f). In these cases, open surgical decompression and spine stabilization is indicated. However it should be kept in mind the these highly vascularized lesions can lead to significant blood loss during open surgery. A preoperative embolization should be strongly considered. En bloc resection techniques without violation of the hemangioma can also reduce blood loss.

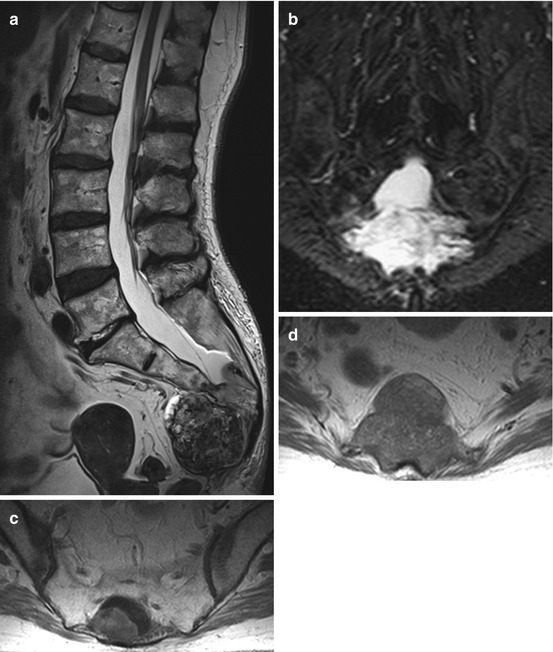

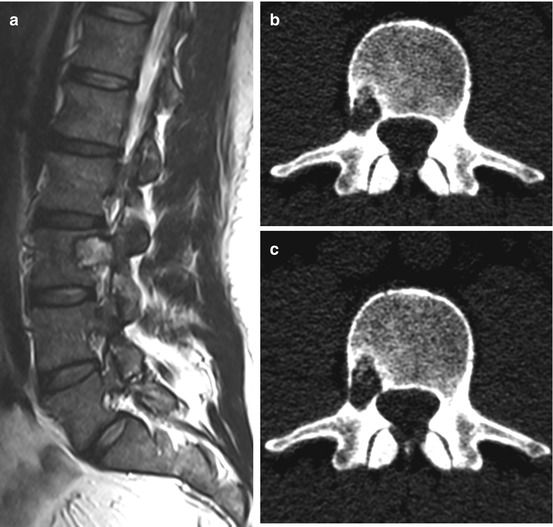

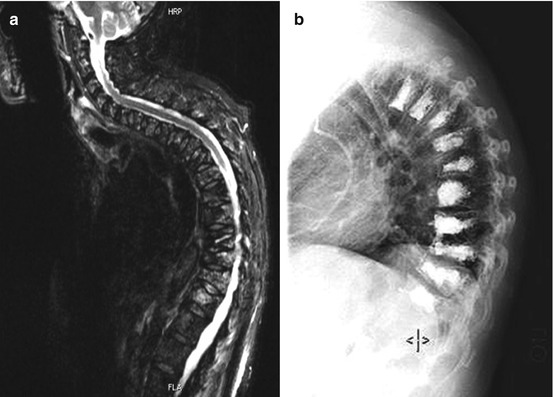

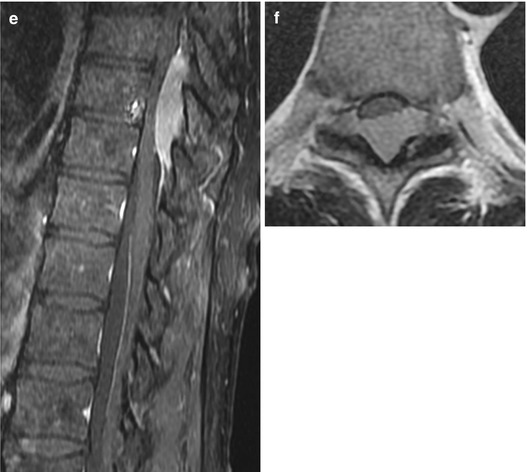

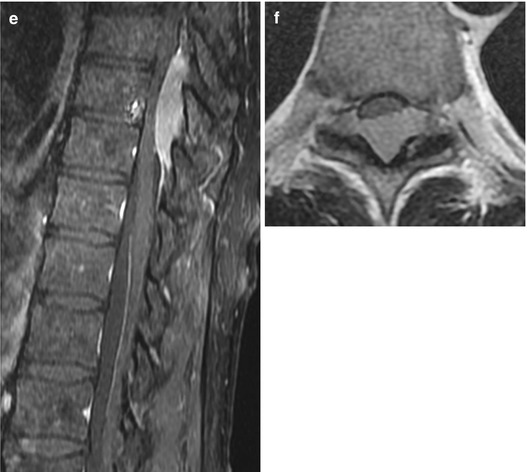

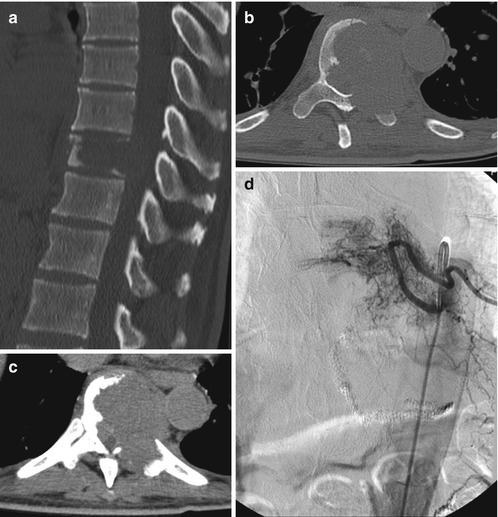

Fig. 11.2

Typical hemangioma shows a hyperintense signals on T1- and T2-weighted images reflecting adipose tissue within the stroma. Aggressive hemangiomas (a–f) however show atypical MRI features with hypointense signals on T1- (a) and hyperintense signals on T2-weighted images and on STIR sequences (b, c). Because of the vascularised stroma within an osseous matrix of bone erosion with interspersed thickened vertical trabeculae, hemangiomas show a high gadolinium uptake (d) and on CT a “honeycomb” appearance

11.2.3 Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

Aneurysmal bone cysts are cystic lesions with differently sized cavities filled with fluid and clotted blood separated by fibrous septa and do not have an endothelial lining. However, even if the histological pattern is benign with absence of atypical mitoses, aneurysmal bone cysts sometimes show rapidly progressive growth with destruction of the bone. They can affect every bone in the body and arise de novo as primary aneurysmal bone cysts or complicate other bone tumours as secondary aneurysmal bone cysts. Therapy of choice is surgical intralesional curettage/resection. If the cyst is large and needs extensive surgery, preoperative embolization should be considered.

11.2.4 Osteoid Osteoma/Osteoblastoma

These tumour are most common in adolescents and young adults. Osteoid osteomas and benign osteoblastomas belong to the same tumour entity and are only differentiated by size. Osteoid osteomas larger than 1.5 cm2 are referred to as osteoblastomas. Osteoid osteomas are typically found in long bones whereas osteoblastomas are more frequent in the spine. Histologically they do have a nidus consisting of bony trabeculae with intervening vascular tissue and are preponderantly slowly growing benign tumours; however, very rarely, osteoblastomas show a more aggressive behaviour and histological appearance. Patients with osteoid osteomas almost always present with pain as the major symptom which is promptly relieved by Non steroidal antiinflammatory drugs NSAIDs, especially by aspirin. Pain from osteoblastomas, in contrast, is usually not influenced by NSAIDs. Therapy of choice is surgical resection. In osteoid osteomas it is sufficient to do an intralesional resection whereas marginal en bloc resection is the best option for osteoblastomas.

11.2.5 Osteochondroma

Osteochondromas are the most common benign bone tumours usually found in long bones and rarely in the spine (4 % of the solitary osteochondromas). Osteochondromas are benign low grade lesions which consist of columnar cartilage and maturing bone surrounded by a fibrous capsule. Therapy of choice is surgical en bloc resection.

11.2.6 Chordoma

Chordomas derive from remnants of the notochord. They are usually found in midline structures of the skull base which is the most common region of origin. Within the spine, chordomas develop most often in the sacrum (~50 %) followed by the cervical spine. Chordomas are composed of cells arranged in small clusters or cords within a myxoid matrix. CT scans show soft tissue mass and usually osteolytic lesions. On T1WI MRI chordomas are hypo-/isointense and on T2WI hyperintense, depending on the fibrous tissue component (Fig. 11.3a–d). The most important differential diagnosis is chondrosarcoma. Chordomas show a strong keratin and S100 immunoreactivity while chondrosarcomas are only S100 immunopositive. Chordomas are slowly but locally aggressive growing tumours and therefore have to be resected en bloc whenever technically feasible.

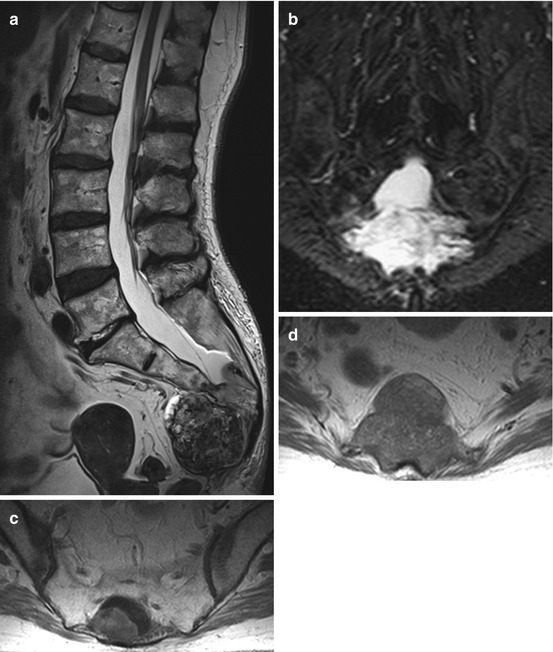

Fig. 11.3

Chordomas are midline tumours with destructive growth patterns (a–d). On T2WI they are hypo- to hyperintense depending on the fibrous tissue component (a, b). Sacral chordomas usually have a large presacral tumour component (a). On T1WI chordomas are hypo-/isointense (d) and show a heterogeneous enhancement

11.2.7 Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcomas arise from neoplastic chondrocytes. Low grade chondrosarcomas are mild to moderately hypercellular tumours, whereas high grade chondrosarcomas show increasing nuclear atypia, sometimes associated with necrosis. Chondrosarcomas are immunopositive for S100 but not for keratin. They are rare lesions occurring most often in patients between 30 and 50 years of age and are most common in the thoracic spine. The prognosis is always dependent on the possibility of a local recurrence. Intralesional resections of chondrosarcomas are associated with high recurrence rates of up to 100 %. Therefore it should be the aim to do a complete “en-bloc” resection if possible. If a complete “en-bloc” resection is achieved, the local recurrence rate is given as 20 % in the literature. Chondrosarcomas are not sensitive to conventional radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

11.2.8 Giant Cell Tumour

Giant cell tumours are locally aggressive semi-malignant tumours most frequently found in the sacrum. They usually occur in younger patients with immature skeletal system. Histologically they are composed of giant cells resembling osteoclast and spindle- to ovoid-shaped mononuclear stromal cells. These mononuclear stromal cells are thought to be the neoplastic component of these tumours, the osteoclast-like giant cells being considered as non-neoplastic reactive tumour components. Giant cell tumours sometimes spread to the lung. They are usually highly vascularised tumours, and therefore a preoperative embolization should be considered before surgery. “En-bloc” resection is the therapy of choice.

11.2.9 Brown Tumour

Brown tumours are bone lesions associated with hyperactivity of osteoclasts as seen in hyperparathyroidism. Brown tumours are non-neoplastic lesions and typically found in long bones. Spinal involvement is exclusively seen in primary hyperthyroidism. The primary therapy consists of medical treatment of the causal condition. Surgery is only indicated in cases of acute neurological deterioration and instability despite adequate therapy of the causal condition.

11.2.10 Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia is a non-malignant fibroosseous disorder of the skeletal system significant for the replacement of the normal bone with fibrous tissue and irregular osteoid. Besides the skeletal system, other organs may be involved (McCune Albright syndrome). Fibrous dysplasia usually affects one bone (monostotic form ~ 70–80 %); less frequently, more than one bone is affected (polyostotic form ~ 20–30 %). Spinal involvement is very rare and can be monostotic or polyostotic. Patients with spinal fibrous dysplasia have an increased risk of vertebral body fracture and of the development of a secondary osteosarcoma. Therapy is symptomatic to control pain. Surgery is reserved for complications such as spinal instability or neurological compromise by spinal cord or nerve root compression.

11.2.11 Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis/Eosinophilic Granuloma

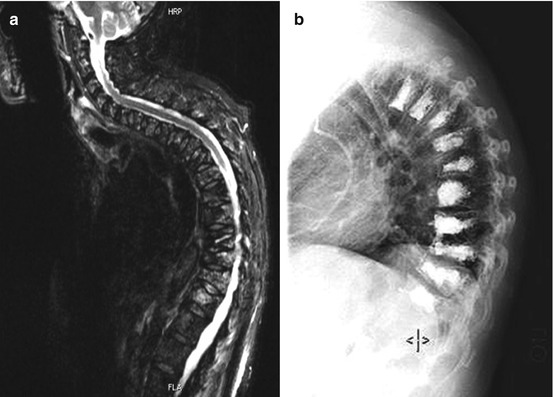

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is an abnormal proliferation of histiocytes resulting in focal or multiple granulomatous lesions of the bone. The clinical spectrum reaches from focal bone lesions to multifocal multisystem disease. Langerhans cell histiocytosis can affect every organ. It shows characteristics of both malignant and non-malignant diseases and it is still unclear whether Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a true neoplasm or an inflammatory process. Eosinophilic granuloma is the localized type of the Langerhans cell histiocytosis and shows a localized uni- or multifocal bone involvement being observed in around 70 % of patients with histiocytosis. Hand–Schüller–Christian disease is significant for localized bony involvement, usually the skull, with exophthalmus and diabetes insipidus caused by the involvement of the pituitary stalk. This type of Langerhans cell histiocytosis is seen in about 15–40 % of the cases. Abt–Letterer–Siwe disease refers to the disseminated form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis which occurs in around 10 % of the cases. Although Langerhans cell histiocytosis can occur in every age, it is usually diagnosed in the pediatric population and younger adults. In children the incidence is estimated to be 3–5 per 1,000,000. Around 8–15 % of eosinophilic granulomas affect the spine and can cause pain and instability as well as neurological compromise (Fig. 11.4a–d). Very often eosinophilic granuloma is self limiting and results in spontaneous resolution, and therefore therapy should be conservative and address predominantly the pain symptoms. Surgery is reserved for cases with spinal instability, intractable pain or neurological compromise caused by spinal cord or nerve root compression. In cases with multifocal or multisystem disease, radio- and chemotherapys are treatment options.

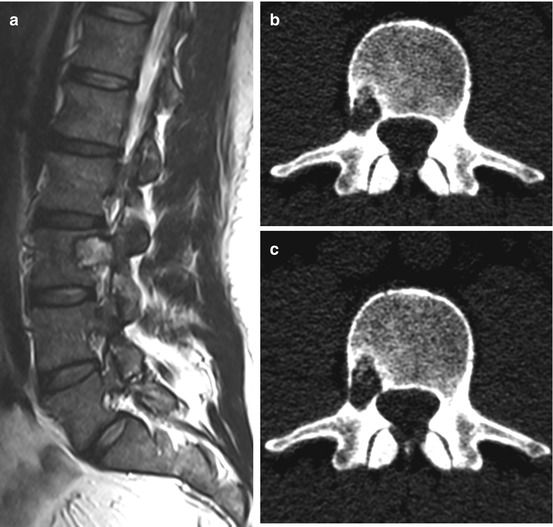

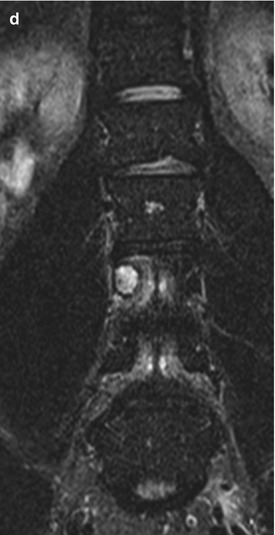

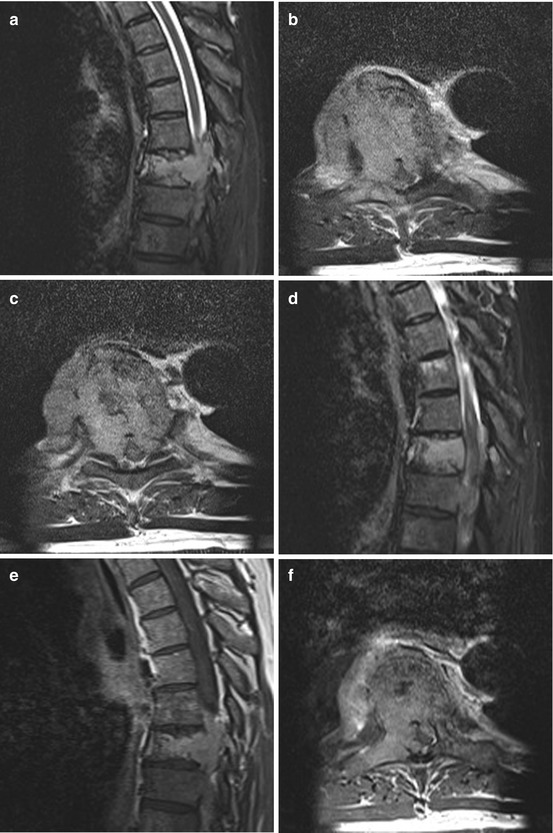

Fig. 11.4

Eosinophilic granuloma is a lytic non-sclerotic lesion (b, c) which usually does not enter the disc space, nor the epidural space or the paravertebral region. T2WI show a high signal soft tissue mass (a, d)

11.2.12 Solitary Plasmacytoma/Multiple Myeloma

Plasmacytoma/multiple myeoloma is a neoplastic disorder of the antibody producing plasma cells. It belongs to the B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas and occur with an incidence of 4–6 per 100,000 per year. The terms plasmacytoma and myeloma are often used synonymously, although, strictly speaking, only one solitary intramedullary or one extramedullary focus are referred to as plasmacytoma without systemic involvement; multiple intramedullary foci are referred to as multiple myeloma. Around 55 % of all solitary plasmacytomas affect the spine. Usually they are located within the vertebral bodies but can cause osteolytic lesions with pathologic vertebral body fractures and extend to the spinal canal with subsequent spinal cord compression (Fig. 11.5a–l). Spinal manifestation per se is not an indication for surgery, because solitary plasmacytoma/multiple myeloma is sensitive to radio- and chemotherapy. Painful pathologic fractures can be treated successfully with kypho- or vertebroplasty (Fig. 11.6a, b). Open surgery is indicated in patients with high grade spinal instability and progressive neurological deficits.

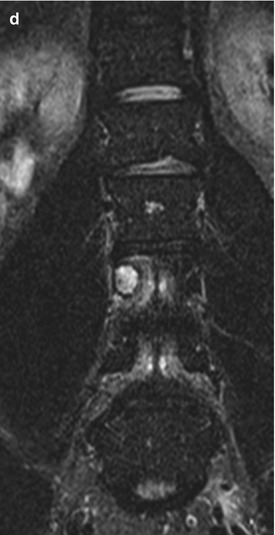

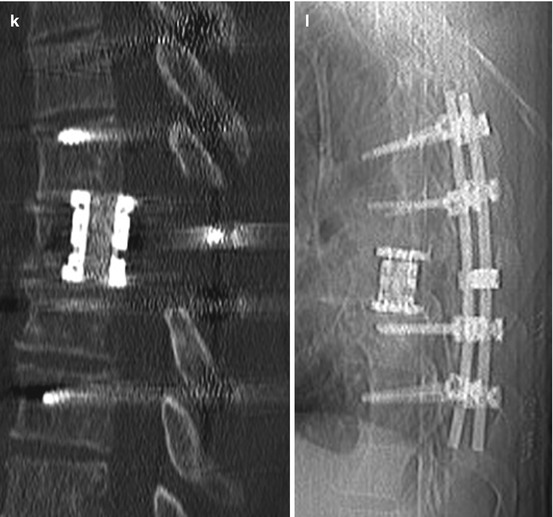

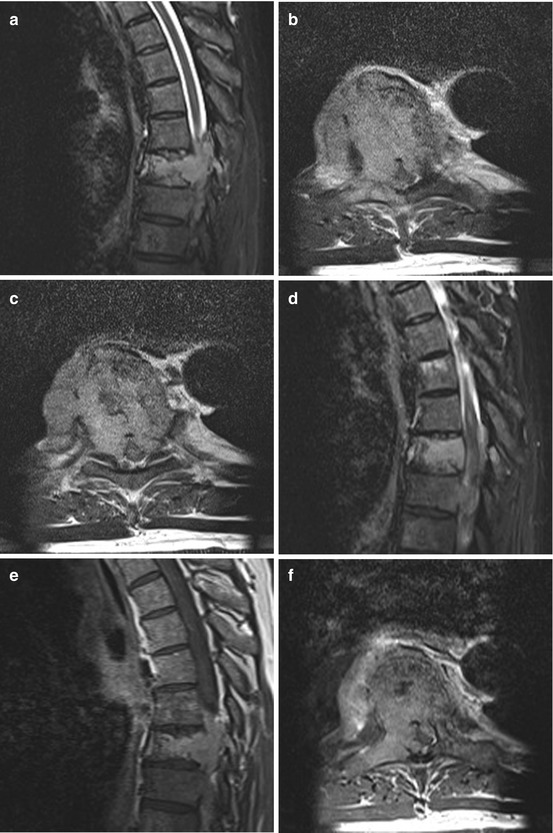

Fig. 11.5

Solitary plasmacytoma shows a lytic tumour with sclerotic margins. (h, i) On T1WI it is an iso- or slightly hyperintense tumour mass with homogenous enhancement. (e–g) On T2WI it can show a variable hyperintensity. (a–c) In this case the tumour has entered the spinal canal with high grade spinal cord compression. (a–g) Because of the significant bone destruction with subsequent instability therapy was surgical with vertebrectomy, tumour resection, anterior reconstruction with cage and posterior instrumentation over dorsoventral approach (j–l)

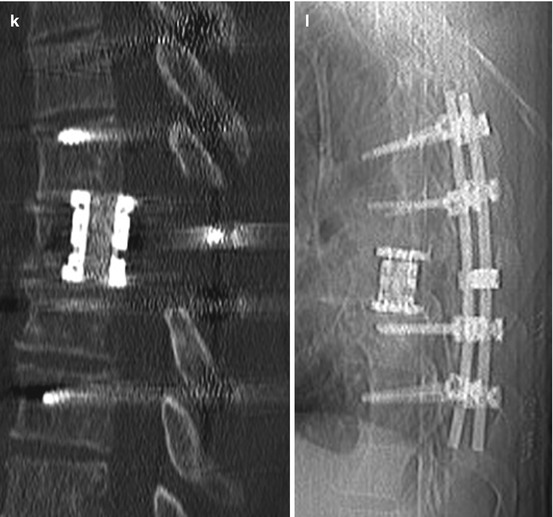

Fig. 11.6

Multiple myeloma with involvement of several vertebral bodies can lead to pathological fractures with significant pain (a). Kypho- and vertebroplasty is a minimally invasive therapy option which can usually address pain from multiple pathologic fractures in patients with multiple myeloma (b)

11.2.13 Lymphoma

Spinal lymphomas arise from the bone marrow of the vertebral body, infiltrate the bone of the vertebral body and extend per continuitatem to the epidural space or metastasize hematogenously from extraspinal sites to the epidural space (Fig. 11.7a–f). Spinal lymphomas are usually non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Therapy of choice is chemo- and radiotherapy. Surgical therapy is reserved for cases with instability and acute neurological deterioration caused by spinal cord compression. Spinal cord compression without involvement of the vertebral body is amenable to sole decompressive surgery.

Fig. 11.7

Lymphoma of the epidural space without involvement of the vertebral body. On T2WI lymphomas can have hypo- to isointense signals (a, b) and usually enhance uniformly (c–f)

11.2.14 Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is a common bone tumour; however, primary spinal osteosarcomas are rare at around 2 % of all osteosarcomas. Histologically they consist of malignant spindle or round cells which form osteoid. Risk factors for the development of an osteosarcoma are preexisting bony pathologies such as Paget’s disease or osteoblastomas and radiation therapy. Pain is the most common presenting symptom in patients with spinal osteosarcomas. Treatment consists of a combination of chemotherapy, en bloc resection when technically feasible and postoperative radiation. However, because of the aggressiveness of the tumour, the prognosis is poor.

11.2.15 Ewing Sarcoma

Ewing sarcoma is the most common malignant bone tumour in children. It usually affects long bones; primary spinal involvement is rare and occurs in less than 10 % of cases. Of the primary spinal Ewing sarcomas, the sacrum is the most common localization. Ewing sarcomas are chemo- and radiosensitive. Therefore surgery is limited to acute neurological deterioration and biomechanical instability.

11.2.16 Fibrosarcoma

Fibrosarcoma is a rare soft tissue tumour which arises typically from the fascia of the deep musculature and the periosteum. It consists of proliferating fibroblasts and anaplastic spindle cells. Known risk factors for fibrosarcomas are conditions such as fibrous dysplasia, radiation therapy and Paget’s disease. Fibrosarcomas usually involve the soft tissue of the extremities and the trunk. The spine is a rare location. In bones, surgical radical resection is the standard therapy for fibrosarcomas. Chemotherapy may be administered neoadjuvantly or adjuvantly. Typically fibrosarcomas are not very radiosensitive.

11.2.17 Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma is a soft tissue sarcoma which occasionally occurs in bone and very rarely as a primary spine tumour. Treatment consists primarily of radical resection if possible. Sometimes radiation is indicated. The role of chemotherapy in the treatment of fibrous histiocytoma is controversial at the present time.

11.2.18 Sacrococcygeal Teratoma

Sacrococcygeal teratoma is the most common extragonadal germ tumour in children, with an incidence of 1 in 350,000 live births, usually located in front of the sacrum. They consist of entodermal, ectodermal and mesodermal derivatives and have a potential to be malignant. Sacrococcygeal teratoma has been classified into four types according to their extent outside and inside the body. Type 1 tumours are completely outside the body, sometimes connected with a narrow stalk. Type 4 tumours are completely inside the body in a presacral/retrorectal location. Therapy depends on the size of the tumour and the age of manifestation. Beside close observation, complete resection is the favourite treatment option.

11.3 Secondary Malignant Epidural Tumours

11.3.1 Metastases

11.3.1.1 Prevalence

The spinal column is the most frequent site of bone metastasis. Metastatic spinal disease is a significant problem for a large number of patients: spinal metastases develop in 5–10 % of all patients with cancer during the course of their disease. Approximately 40 % of persons dying of cancer have autopsy evidence of spinal metastases. Of these, 10 % experience spinal cord compression with subsequent neurological deficits. The annual incidence of spinal cord compression caused by spinal metastases is estimated to be 20,000 cases. In recent autopsy studies, investigators found metastatic involvement of the spine in 90 % of patients with prostate carcinoma, in 75 % of those with breast carcinoma, in 55 % of those with melanoma, in 45 % of those with lung carcinoma, and in 30 % of those with renal carcinoma. Specific carcinomas cause clinically significant spinal cord compression in a higher percentage of patients. Twenty-two percent of patients with breast cancer, 15 % of those with lung cancer and 10 % of those with prostate carcinomas experience symptomatic spinal cord compression.

11.3.1.2 Symptoms

Symptoms of secondary spine tumours do not differ significantly from malignant primary spine tumours. In most cases spinal metastases present with mechanical back pain because of instability and/or radicular pain. When the metastatic tumour enters the spinal canal and compresses the spinal cord, an acute neurological deterioration with transverse spinal cord syndromes are often seen. Symptoms progress much more rapidly in metastases than in primary malignant extradural tumours.

11.3.1.3 Diagnosis

Metastatic cancer is a systemic disease. Therefore an oncological staging is very important and should answer the question of life expectancy. Preoperative MRI of the whole spine reveals further metastases which may cause instability and may have to be addressed surgically. CT scans are important for exact measurement of the pedicles and the implants and to evaluate the quality of bone. In highly vascularised metastases (renal cell, thyroid) it is recommended to perform a preoperative angiography with embolization, since intralesional resections of these tumours can cause massive blood loss (Fig. 11.8a–h).

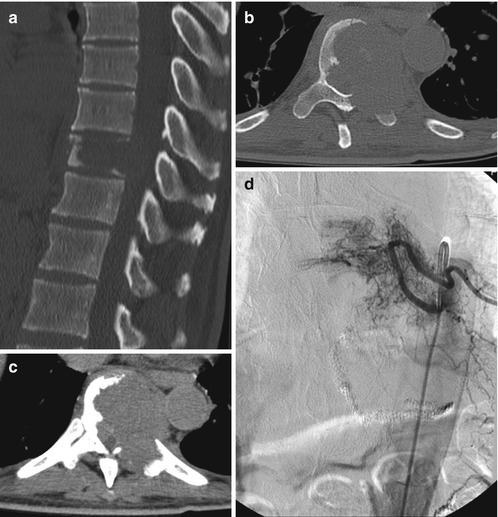

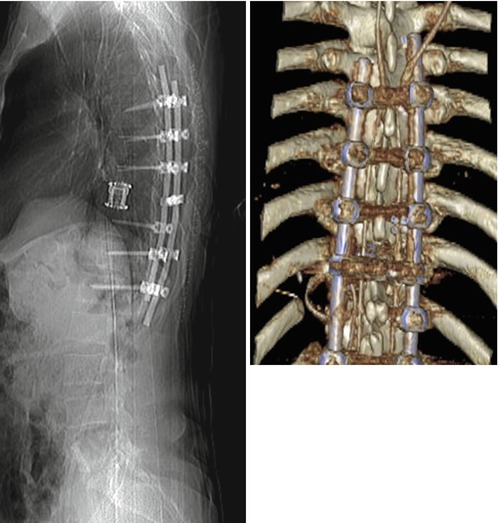

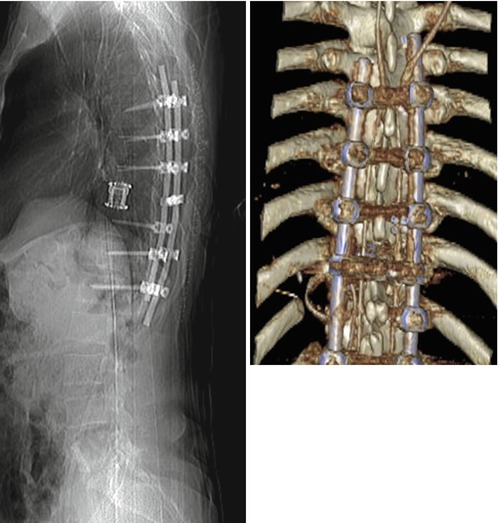

Fig. 11.8

Case with an osteolytic metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma with destruction of the larger part of the vertebral body, the left pedicle and transverse process, the facet joint and the left lamina (a, b). The tumour has entered the spinal canal with subsequent spinal cord compression (c). Because of the primary renal cell carcinoma, a preoperative angiography was carried out, demonstrating the high vascular supply (d). Embolization could significantly reduce the vascularization (e) and the patient underwent a single-stage posterolateral transpedicular vertebrectomy with anterior reconstruction with expandable cage and posterior instrumentation with a screw rod system (f–h)

11.3.1.4 Therapy

Surgical treatment options are decompression by anterior and posterior approaches as well as minimally invasive treatment with vertebro- or kyphoplasty. Possible non-surgical treatments for metastatic spinal tumours include radiotherapy alone, radiotherapy plus systemic chemotherapy, hormone therapy, surgical decompression followed by radiotherapy, and, more recently, extracranial radiosurgery. Traditionally, spinal metastases have been treated by surgical decompression over a posterior approach with a single or multilevel laminectomy to treat radicular pain and spinal cord compression. However, several studies carried out in the 1980s, including a randomized clinical trial, have shown that the outcome after surgical decompression followed by radiotherapy is not superior to treatment by radiotherapy alone. These studies led to the abandonment of surgical decompression by laminectomy alone and resulted in treatment of spinal metastases by radiotherapy alone. However, with the advent of more sophisticated techniques for complex spine reconstruction, and because of the fact that simple laminectomy and radiotherapy do not address biomechanical instability, a main feature of spinal metastases, spine surgeons started again to treat spinal metastases more aggressively compared to simple laminectomy with subsequent stabilization of the spine. Recent studies have shown that surgical decompression with complex spine reconstruction can successfully improve the neurological status, improve severe pain and restore biomechanical stability. One well designed randomized clinical trial could show that, in a selected patient group with spinal metastases, the neurological outcome and the survival after surgical decompression with subsequent stabilization followed by radiation is better than with radiation therapy alone. The present generally accepted treatment algorithm embraces that, when a metastatic spinal tumour causes compression of the spinal cord or other neural elements, surgical decompression is often chosen. Based on the extent of spinal column destruction and the resulting biomechanical instability of the spine, fixation may be elected. The goal of both surgery and local radiation therapy in the treatment of spinal metastases in the majority of patients is basically palliation of painful symptoms, prevention of pathological fractures of the vertebral body, and halting or reversing progression of neurological compromise rather than a curative concept (Fig. 11.9a–c). However, in single metastases from slowly growing tumours (renal cell, thyroid cancer) a curative therapeutic concept may apply with a radical “en-bloc” resection of the spinal metastasis. The role of radiosurgery has yet to be defined but is likely limited to treatment of focal or recurrent disease or use as a supplement to fractionated radiotherapy.