(1)

Princeton Spine & Joint Center, Princeton, NJ, USA

Keywords

ZygapophysealMedial branchRadiofrequency rhizotomyDouble-block paradigmIntra-articular injectionExtension biasedFacet joint pain is the second most common cause of chronic lower back pain, accounting for approximately 15 % of cases in younger patients and approximately 30 % of patients older than 60 [1]. Recall from Chap. 1 that the facet joints are the hinge joints in the spine that allow trunk flexion and resist extension and rotation. Facet joints are synovial joints and as such have the same basic parts as the other mobile joints in the human body such as the knee, shoulder, hip, and finger. For this reason, their technical name in the spine is zygapophyseal joints. However, they will be referred to as facet joints in this book as this is the common accepted medical practice. Pain may occur in the facet joint because of arthritis, cartilage tearing, or capsular tearing.

It is important to recognize at the outset that arthritis of the facet joints is ubiquitous. A cadaveric study that included 647 lumbar cadaveric spines, led by Dr. Eubanks, found that more than half of people between the ages of 20 and 30 reveal facet joint arthritis, and 100 % of people after the age of 60 had facet joint arthritis [2]. From this and other studies, it is clear that imaging studies of patients with suspected facet joint pain must be taken with a grain of salt since asymptomatic arthritic findings are so common [3]. Indeed, the diagnosis of facet joint pain, even in younger patients, cannot be made on imaging alone.

There are features of facet joint pain that are considered “typical” of facet joint arthropathy causing lower back pain. Positions that increase pressure on the facet joints (standing, extending backward) tend to exacerbate facet joint pain, and positions that reduce pressure (sitting, bending forward) tend to decrease pain. Facet joint pain tends to be described by patients as dull and aching. Facet joint pain tends to be more common in patients who participate in extension biased activities (e.g., gymnastics, football) or who are older than 60 years of age.

f the following patient. Elaine is a 66-year-old female with a 2-year history of progressively worsening axial lower back pain. The pain is dull and aching and worse with standing and better with sitting. The pain is worst with prolonged standing still. If she is standing for a while and the pain is getting worse, she says that sitting will make the pain better. The pain does not radiate into the legs. She denies any neurologic symptoms in the legs. On physical examination, she has pain with trunk extension and oblique extension bilaterally. An MRI is obtained, and it is normal except for multilevel facet joint arthropathy that is most pronounced at L4–L5 and L5–S1.

Most spine specialists would agree that it certainly sounds like Elaine probably has facet joint pain. As with discogenic pain and other chronic lower back pain diagnoses, this is one of those instances when the research does not line up particularly well with our collective clinical experiences. While mechanically, it makes sense and is consistent that Elaine’s pain is probably from facet joint pain, the research suggests that she still may have discogenic lower back pain or another source of her pain [4, 5].

It is fine to treat Elaine conservatively with the presumptive diagnosis of facet joint pain. However, in order to confirm the presence of facet joint pain, it is necessary to perform diagnostic injections. Diagnosing facet joint pain is a topic in which academic medicine sometimes uncomfortably collides with clinical medicine. There are two ways to diagnostically assess a facet joint with an injection. The joint itself can be injected with a fluoroscopically guided intra-articular facet injection. The other injection that can be performed is a diagnostic block of the medial branch of the dorsal ramus that innervates the suspected facet joint. There are advantages and disadvantages to each approach.

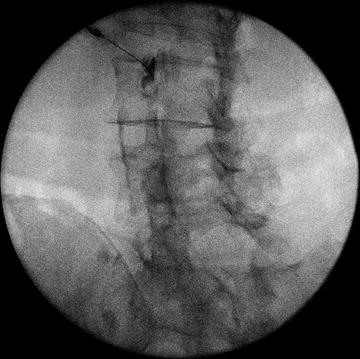

Intra-articular facet joint injections are the more common approach of a first diagnostic injection (Fig. 6.1). The advantage of an intra-articular facet joint injection is that steroid can also be used in the injection giving it the potential to be both diagnostic and potentially therapeutic. Part of the degenerative process may be a degradation of integrity of the facet joint capsule which may render it effectively incompetent. The problem diagnostically then with an intra-articular injection is that when the medicine is injected into the facet joint, if the capsule is incompetent, some of the medicine may spill over through a leaky facet joint capsule into adjacent structures making the diagnostic assessment less exact. Further, research has not shown that intra-articular facet joint steroid injections have long-term efficacy for treating facet joint pain. Indeed, the research that has been done tends to reveal that facet joint injections work about as well as injecting placebo for providing facet joint pain relief. However, this research tends to strictly assess the efficacy of an injection of the facet joints in isolation [6–13]. As with any joint, if the joint is just injected with steroid, the pain will tend to recur. For this reason, if a steroid injection is performed, it should be viewed as offering the patient a window of opportunity for him to perform physical therapy exercises and improve his biomechanics and ergonomics so that the stresses being placed on the joints are shifted and the pain does not recur when the steroids have ceased being effective.

Fig. 6.1

Left oblique fluoroscop ic image of a left L4–L5 intra-articular facet joint injection with contrast enhancement confirming the flow along the joint line

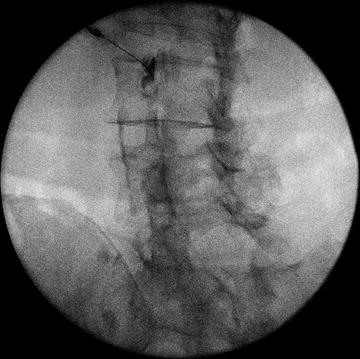

The advantage of a diagnostic medial branch block is that very little anesthetic is used to block the medial branch and so the medicine does not have the opportunity to “spill over” into adjacent structures (Fig. 6.2). The disadvantage is that there is no significant therapeutic value to the injection (although some studies do suggest a small percentage of patients improving long-term after a medial branch block).

Fig. 6.2

Needle placement at the left L2 medial branch, with contrast enhancement of the junction of the left transverse process and the superior articular process of the L3 vertebra

In clinical practice, the gold standard diagnostic approach to diagnosing facet joint pain is to follow a double-block paradigm [14]. In this approach, the patient undergoes two medial branch block procedures on different days. In one of the blocks, the doctor uses 2 % lidocaine to block the medial branch. In another block, on a different day, the doctor uses 0.25 % bupivacaine. Ideally, neither the doctor nor the patient knows which anesthetic is used on the given day (in the real world the patient typically does not know but for practical reasons the doctor generally does). For the test to be considered positive, the patient should not only have complete pain relief with both blocks, but the pain relief should last for fewer hours using the lidocaine (because it is a shorter-duration anesthetic) than with the bupivacaine.

When performing a diagnostic block of a facet joint (or any other structure), it is important to recognize that complete or near-complete pain relief does not necessarily have to mean that all of the pain is relieved. Rather, a discrete portion of the pain must be completely or nearly completely relieved. It is not unheard of for a patient to have multifactorial pain. It is possible, for example, for a patient to have facet joint pain and sacroiliac joint pain. When the facet joint pain is blocked, part of the pain in the lower back may be completely resolved but the buttock pain persists. In this instance, it would be said that the facet joints are responsible for the lower back pain but not the buttock pain and this is still a positive response to the diagnostic test. Alternatively, the lower back pain may be relieved by the diagnostic test, but the upper part of the lower back pain may remain, and this may be due to a different cause such as discogenic back pain. It is therefore very important to explain this to the patient when giving the patient a pain diary to fill out. Another important instruction for the physician to give the patient when explaining a pain diary is that the patient should only concern herself with the response of the patient’s typical pain. There may be pain from the needle, but this pain should be ignored as best as possible and the patient should focus on the response of the typical pain.

When performing a d iagnostic block, whether a medial branch block or intra-articular facet joint block, it is important to not anesthetize the subcutaneous tissue or overlying muscles. To the extent that pain relief is felt, it is important that it only be felt because the targeted structure was anesthetized and not the overlying tissue. If a 25 gauge needle is used for the procedure, the patient typically can tolerate the procedure very well despite a lack of numbing of the overlying structures.

The reason for two diagnostic blocks of the facet joints is that one diagnostic block yields an approximate 32 % false-positive rate (meaning about a third of patients have a false-positive or placebo response). When the two block paradigm is used as described above, that false-positive rate drops to about 8 %, which is generally deemed acceptable in clinical practice. For research purposes, a third diagnostic block is sometimes used and that diagnostic block is placebo. The three-block paradigm is the true gold standard diagnostic approach for research purposes. In the three-block paradigm, strict double-blind protocol is used, and the patient must have no pain relief with the placebo block, complete relief to the lidocaine, and longer-acting complete relief to the bupivacaine in order to diagnose the pain as positively from the facet joint. While this truly is the gold standard diagnostic for facet joint pain, in clinical practice it is generally not deemed ethical to inject a patient with placebo so the 8 % false-positive rate is considered acceptable [14].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree