Factitious Disorder and Malingering

Christopher Bass

David Gill

Factitious disorder

Introduction

Patients with factitious disorder feign or simulate illness, are considered not to be aware of the motives that drive them to carry out this behaviour, and keep their simulation or induction of illness secret. In official psychiatric nomenclature, factitious disorder has replaced the eponym Munchausen syndrome, introduced by Asher(1) to describe patients with chronic factitious behaviour. Asher borrowed the term from Raspe’s 1785 fictional German cavalry officer, Baron Karl von Munchausen, who always lied, albeit harmlessly, about his extraordinary military exploits.

The criteria for factitious disorder in DSM-IV(2) are (a) the intentional production or feigning of physical or psychological signs or symptoms; (b) motivation to assume the sick role; and (c) lack of external incentives for the behaviour (e.g. economic gain, avoidance of legal responsibility, or improved physical well-being, as in malingering) and lack of a better classification for the disorders.

In the last 10 years there has been increased interest in deception in medical practice, with specific focus on pathological lying and the diagnostic dilemmas in this field: specifically, how to differentiate between hysteria, factitious disorders, and malingering. Some of these topics will be discussed in the next section.

This chapter concentrates on factitious physical complaints; fabricated psychological symptoms are considered under malingering.

Diagnostic problems

The DSM-IV criteria have recently come under attack. Turner(3) has argued that criterion B (motivation to assume the sick role) has no empirical content and fulfils no diagnostic function. He also argues that criterion A, the intentional production of physical or psychological signs or symptoms, emphasizes symptoms and cannot accommodate pseudologia fantastica (PF), voluntary false confessions, and impersonations. He concludes that the two criteria need reformulating in terms of lies and self-harm, respectively. Bass and Halligan(4) have also suggested that because the conceptual justification for factitious disorders is ‘empirically unsubstantiated’ and the motivation for diagnostic purposes (conscious versus unconscious; voluntary versus involuntary) essentially unknowable, it seems reasonable to question the clinical status and legitimacy of factitious disorder. More recently there has been a resurgence of interest in pathological lying, because this is often easier to identify than, for example, the degree of ‘voluntariness’ or ‘motivation’ to attain the sick role (however that is defined).

Pathological lying (pseudologia fantastica): a key component of factitious disorder

It is possible to identify pathological lying if the clinician has sufficient information at his disposal (most often the medical notes). If the patient reports, for example, that they are being treated for leukaemia, and when there is evidence that contradicts this, then this suggests dissimulation. On some occasions the patient will admit to lying, but this is rare.

Because pathological lying is often a key component in factitious disorders, evidence for it should be actively sought by the clinician. But what distinguishes the pathological liar from the person who just lies a lot? Dike et al.(5) suggest that the diagnosis is made when lying is persistent, pervasive, disproportionate, and not motivated primarily by reward or other external factors. They also suggest, however, that a key characteristic of pathological lying may be its compulsive nature, with pathological liars ‘unable to control their lying’. Psychiatric conditions that have been traditionally associated with deception in one form or another include malingering, confabulation, Ganser’s syndrome, factitious disorder, borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. Lying may also occur in histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders. It is important to note however that pathological lying can occur in the absence of a psychiatric disorder, and that there may be different types of pathological lying, e.g. the benefit fraudster and the stereotypical wandering Munchausen patient describe different subgroups. Furthermore, it has been reported that up to 40 per cent of cases of pseudologia fantastica have a history of central nervous system abnormalities, which suggests that brain dysfunction in these patients requires closer study.(6)

In recent years, functional neuroimaging techniques (especially functional magnetic resonance imaging) have been used to study deception. Attempted deception is associated with activation of executive brain regions (particularly prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices), while truthful responding has not been shown to be associated with any areas of increased activation (relative to deception).(7) Furthermore, Yang et al.(8) reported that pathological liars showed a 22-26 per cent increase in prefrontal white matter and a 36-42 per cent reduction in prefrontal grey/white ratios compared with both antisocial controls and normal controls. These findings suggest that increased prefrontal white matter developmentally provides a person with the cognitive capacity to lie, although Spence(9) has urged caution in the interpretation of these results.

Clinical features of factitious disorder

Clinical features are diverse, and attempts to subtype patients have not always been helpful. The majority of patients with factitious disorders are non-wandering, socially conformist young women (often nurses) with relatively stable social networks.(10, 11 and 12) These patients

are likely to enact their deceptions in general hospitals, especially accident and emergency departments, and the liaison psychiatrist should be alert to these clinical problems, which can be referred from a variety of different medical and surgical specialties.

are likely to enact their deceptions in general hospitals, especially accident and emergency departments, and the liaison psychiatrist should be alert to these clinical problems, which can be referred from a variety of different medical and surgical specialties.

Factitious disorders typically begin before the age of 30 years;(13, 14) there are often prodromal behaviours in childhood and adolescence (see below). These individuals often report an unexpectedly large number of childhood illnesses and operations, and many have some association with the health care field.(10) High rates of substance abuse, mood disorder, and borderline personality disorder have been reported.(10,12) Approximately four-fifths of factitious disorder patients are women, and 20-70 per cent work in medically related occupations.(12)

Clinicians should be alert to the presentation of more exotic forms of factitious presentation. For example, some women present themselves to family cancer or genetic-counselling clinics and provide a false family history of breast cancer to their medical attendants.(15) Another recent example is ‘electronic’ factitious disorder,(16) used to describe patients who falsify their electronic medical records to create a factitious report (e.g. of cancer). Another important group is encountered in pregnancy, and this will clearly have important implications for child protection.(17)

In medico-legal practice factitious disorders have been described in patients with a diagnosis of reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), specially involving the forearm,(18) and others have reported that the abnormal movements commonly associated with RSD (CPRS Type I) are consistently of somatoform or malingered origin.(19) Cases have been described where patients involved in litigation have died of factors directly related to factitious physical disorder.(20)

It is being increasingly recognized that these disorders can occur in childhood and adolescence, and child psychiatrists need to be alert to factitious presentations, especially in departments of infectious diseases.(21) Unlike adult patients, many of these children admit to their deceptions when confronted, and some have positive outcomes at follow-up. The descriptions of some of these children as bland, depressed, and fascinated with health care are remarkably similar however to adults with factitious disorders.(22)

Classification

Four main subtypes are distinguished in DSM-IV.(2)

1 Factitious disorder with predominantly psychological signs and symptoms. This is more difficult to diagnose than factitious disorder with physical complaints, because there is no way of excluding a ‘true’ psychiatric disorder by physical examination or laboratory investigation: see below under malingering.

2 Factitious disorders with predominantly physical signs and symptoms. Almost every illness has been produced factitiously. However, four subgroups describe most cases(23):

self-induced infections

simulated illnesses, for example adding blood to urine

interference with pre-existing lesions or wounds

surreptitious self-medication, for example self-injection of insulin

These categories are not mutually exclusive or jointly exhaustive.

3 Factitious disorders with combined psychological and physical symptoms

4 Factitious disorders not otherwise specified. This includes factitious disorder by proxy (see below and Chapter 9.3.3).

Diagnosis

Clinicians should become suspicious that a patient may be fabricating symptoms if the following features are noted:

The course of the illness is atypical and does not follow the natural history of the presumed disease, e.g. a wound infection does not respond to appropriate antibiotics (self-induced skin lesions often fall into this category, when ‘atypical’ organisms in the wound may alert the physician).

Physical evidence of a factitious cause may be discovered during the course of treatment, e.g. a concealed catheter, a ligature applied to a limb to induce oedema.

The patient may eagerly agree to or request invasive medical procedures or surgery.

There is a history of numerous previous admissions with poor outcome or failure to respond to surgery (these patients may overlap with the chronic somatoform patient with ‘surgery prone behaviour’).(24)

Many physicians have been consulted and have been unable to find a relevant cause for the symptoms.

Additional clues include the patient being socially isolated on the ward and having few visitors, or the patient being prescribed (or obtaining) opiate medication, often pethidine, when this drug is not indicated. When these findings occur in someone who has either worked in or is related to someone who has worked in the health field, the caregivers should have a high index of suspicion for a factitious disorder. Obtaining collateral information from family members, prior physicians, and hospitals is crucial.

Differential diagnosis

Factitious disorder must be distinguished from authentic medical conditions. It is not uncommon in clinical practice however to find patients with both factitious disorder and coexisting physical illness. For example, patients with brittle diabetes are usually young females who deliberately interfere with their treatment, causing unstable diabetic control.(25) A syndrome of severely unstable asthma (‘brittle asthma’) which also affects young females has also been described;(26) this can occur (especially in A and E departments) with paradoxical adduction of the vocal cords during inspiration.(27) Such patients can neglect to take medication at appropriate times and then ignore adequate management of the potentially dangerous consequences. This may lead to repeated admissions to hospital with medical emergencies such as diabetic ketoacidosis, status asthmaticus, or even pseudo status (simulated status epilepticus).

Factitious disorders are differentiated from somatoform disorders, where physical symptoms, although not caused by physical disease, are deemed not to be intentionally produced. Patients with factitious disorder, although they may state that they are not aware of the motives that drive them, voluntarily produce their physical or psychological symptoms. The disorders may overlap, however, and non-wandering female patients with factitious physical disorders may have more in common with those females who have somatoform disorders than with men with factitious disorder or with malingerers. Fink(28) found that 20 per cent of patients with

persistent somatization (i.e. patients with more than six admissions to the general hospital with medically unexplained symptoms) also had a factitious illness. One of the authors (Christopher Bass) has also found coexisting chronic somatoform and factitious disorders in the female perpetrators of factitious or induced illness.(29)

persistent somatization (i.e. patients with more than six admissions to the general hospital with medically unexplained symptoms) also had a factitious illness. One of the authors (Christopher Bass) has also found coexisting chronic somatoform and factitious disorders in the female perpetrators of factitious or induced illness.(29)

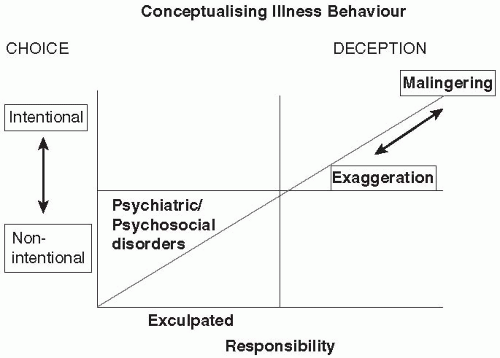

A more difficult distinction is between factitious disorder and malingering. Malingerers, described below, have clear-cut goals, often personal profit, and lack a history of hazardous, unnecessary invasive procedures. In our opinion the boundaries between the two disorders are more porous than the glossaries would have us believe, and we have stated above that the differentiation between conversion disorders, factitious disorders and malingering is extremely difficult in clinical practice. Case reviews have demonstrated how behaviour may shift from somatization to factitious to malingering when patients are followed longitudinally.(30) In our opinion the clinical status and diagnostic legitimacy of factitious disorder as a selective medical disorder is questionable, because it fails to take account of a morally questionable but volitional-based choice to deceive others by feigning illness. Considered as an act of wilful deception, illness deception can be meaningfully conceptualized within a socio-legal or moral model of human nature that recognizes the capacity for choice and the potential for pursuing benefits associated with the sick role. This model, which recognizes the human capacity to exercise free will, is shown diagrammatically in Fig. 5.2.9.1.

Epidemiology

Factitious disorders are relatively uncommon but probably underdiagnosed. Prevalence depends on clinical setting and the investigators’ index of suspicion. Factitious disorder (probably underreported) is probably more common than full-blown Munchausen syndrome (probably overreported). In a recent survey of physicians from Germany, frequency estimates of factious disorder among their patients averaged 1.3 per cent, with dermatologists and neurologists giving the highest estimations.(31)

Of 1288 liaison psychiatric consecutive referrals, seen in a North American general hospital, 0.8 per cent had factitious disorder.(13) Similar figures have been reported by Dutch investigators.(14) Prevalence rates for factitious disorder with psychological symptoms in patients under the age of 65 in a psychiatric hospital are approximately 0.4 per cent.(32)

Aetiology

There is little aetiological information, as large studies are lacking and the self-reported histories of many patients are fallacious. However, a number of themes are apparent(13):

Developmental

Parental abuse, neglect, or abandonment: Many factitious disorder patients experienced significant deprivation in childhood that left them with unfulfilled cravings for attention and care. These patients then seek to gratify these dependency needs by creating illness to obtain the ‘attention and care’ of the medical system

early experiences of chronic illness or hospitalization Medically related

a significant relationship with a physician in the past

experiences of medical mismanagement leading to a grudge against doctors

paramedical employment

Physical

Organic brain disorder: There is increasing evidence that neurobiological factors have a role in some patients, and it has been recommended that screening for evidence of brain dysfunction be carried out in these patients.(33) It is thought however that it is the pseudologia fantastica, and not the factitious disorder per se, that is associated with brain dysfunction (see previous section on Pathological Lying), though such a distinction may be difficult to support in clinical practice.

The authors have found it useful to conceptualize the problem using a cognitive behavioural formulation suggested by Fehnel and Brewer.(34) This allows the assessors to examine for relevant developmental factors and recent life events (especially losses or threatened losses and separations; see Fig. 5.2.9.2).

Course and prognosis

Factitious disorder may be limited to one or more brief episodes, but is usually chronic. For example, of 10 patients identified in a general hospital setting and followed up, at least one was known to have died as a result of factitious behaviour 4 months after the index admission.(13) Only one of the remaining nine patients accepted psychiatric treatment after discharge from hospital. Other authors have, however, reported a less gloomy outcome.(10) Outcome may be determined by how patients are managed, once their deceptions become manifest. Regrettably, the unmasking of the disorder is often the end of the story. Psychological support following hospital discharge may be associated with improved outcome.(10) Non-wanderers with more stable social networks may have a better prognosis than wanderers.(14) Engaging a patient with factitious disorder in long-term psychological treatment occurs so rarely that it often becomes the subject of a case report. One such report, of a 20-year follow-up of a patient with factious disorder with a favourable outcome is, in the opinion of the authors, the exception to the rule.(35)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree