Chapter 20 Falls and their management

Introduction

Falls are ‘events which cause you to come to rest on the ground or other lower level unintentionally, not due to seizure, stroke/myocardial infarction or an overwhelming displacing force’ (Tinetti et al., 1988). Similar definitions abound but the common phrase ‘come to rest’ is misleadingly genteel. Anyone who has heard or seen an adult crash to the floor will be under no illusion: falls can be calamitous and terrifying.

Falls and falling

Any situation that challenges our postural stability has the potential to:

Falls are high on the agenda of those who fund and provide health care. They are a major cause of disability and the leading cause of mortality due to injury in people aged over 75 years (Department of Health (DoH), Website). The economic impact of falls among elderly people in the UK is considerable and increasing. In 1999, there were more than 600 000 A&E attendances, 200 000 hospital admissions and nearly 5000 fatalities in people aged 60 years and over following falls. The total cost to the UK government was almost £1 billion. The National Health Service incurred 59% of the cost (equivalent to the total budget for one Strategic Health Authority, or 3.3 times the total funding earmarked for mental health, coronary heart disease, cancer, and primary care in England) and the Personal Social Services for long-term care incurred the remainder (Scuffham et al., 2003).

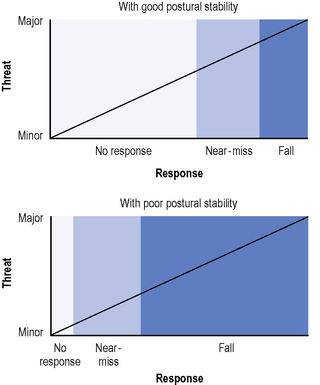

Falls should also be high on the agenda of everyone involved in the rehabilitation of an elderly person or someone with a neurological disorder: it takes less of a challenge to threaten the postural stability of someone with a neurological disorder, for example, than it does someone with an intact system. In the model below (Figure 20.1) someone with good postural stability is likely to fall only after a major challenge; a moderate threat may challenge their stability and register a near-miss; any lesser threat may not even cause a near-miss. Conversely, someone with poor postural stability may fall when faced by even a minor threat. If they have negligible saving reactions, such as someone with acute stroke or advanced PD, almost any threat to their postural stability may result in a fall. As patients progress through rehabilitation, they may acquire the skills to survive the type of moderate threat that previously generated near-misses before they acquire the skills to survive greater perturbation. This may explain the reduction in near-misses, but not in falls observed in a recent fall-prevention trial in Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Ashburn et al., 2007).

To identify a patient at high risk of falling, be aware of the risk factors, use common sense (Haines et al., 2009, showed that physiotherapists were highly accurate in predicting patient falls during rehabilitation) and complete a comprehensive patient assessment (see below). There is no such thing as ‘a faller’; every patient who has fallen is an individual: while an individual carries their risk factors for falling with them 24 hours a day, they only fall at particular moments. The path to preventing someone falling (or, at least, falling again) stems from understanding their fall history in detail (see below), i.e. the circumstances (Stack & Ashburn, 1999) in which they fear falling, have nearly fallen or have actually fallen. It is important not to overlook near-misses, which Skelton (2005) defined as ‘a potential fall corrected’.

Extent of the problem

It is widely believed that approximately one-third of elderly people fall annually. People with neurological conditions also fall frequently and stroke is one of the greatest risk factors (see Ch. 2). Between one-quarter and three-quarters of community-dwelling elderly people with chronic stroke fall over 6 months, with approximately half falling repeatedly, and this population is at high risk of experiencing a fracture. Impairments such as muscle weakness, impaired cognition, sensorimotor dysfunction, and balance and mobility problems presumably contribute to the large number of falls among people with stroke (Marigold and Misiaszek, 2009). Hyndman et al. (2002) identified an association between repeated falls after stroke and impaired mobility, reduced arm function and impaired ability to carry out activities of daily living (ADL). People with PD are twice as likely as are other elderly people to be recurrent fallers (see Ch. 6). As these falls have devastating consequences, there is an urgent need to identify and test innovative interventions with the potential to reduce falls in people with PD. Falls are common in Huntingdon’s disease (see Ch. 7) and targets for physical intervention include gait bradykinesia, stride variability and chorea leading to increased sway, cognitive decline and behavioural change (Grimbergen et al., 2009). Gait disorders, among the most common symptoms in neurology, may play a part in half the falls among these patients (Stolze et al., 2005). Among inpatients, Stolze et al. identified gait symptoms in 93% of patients with PD and 83% with MND. One survey of neurological inpatients suggests that falling leads to 7% of neurological inpatient admissions and that one-third of inpatients fall annually (Stolze et al., 2004).

Causes of falling

Grouped simply, some of the most frequently cited risk factors for falls are:

For a fuller description of the risk factors for falls among elderly people, see the 1996 Effective Health Care Bulletin. The literature mentions more than 400 risk factors for falling. The more risk factors an individual has, the more likely they are to fall (Nitz & Choy, 2008), but, encouragingly, many risk factors are amenable to intervention. In many cases, a multidisciplinary assessment will be necessary, drawing on the skills and expertise of those trained to assess factors ranging from balance and mobility to underlying medical conditions, and multidisciplinary intervention may follow. People who are in pain or who are acutely unwell are at higher than usual risk of falling. Among elderly people with mobility disorders, pain predicts decreased balance and mobility, as demonstrated by Bishop et al. (2007) using the Berg Balance Scale (Berg et al., 1989) and Dynamic Gait Index (Whitney et al., 2003). Falls can be a symptom of urinary tract infection (Rhoads et al., 2007).

Of more importance than the risk factors in themselves is the interaction between them. As Berry and Miller (2008) stated, ‘falls result from an interaction between characteristics that increase an individual’s propensity to fall and acute mediating risk factors that provide the opportunity to fall’. To reduce falls, therapists target the hazardous interactions by identifying the circumstances in which the patient falls and relating them to the pathology, to determine the factors causing falls: these factors are likely to be disease-specific.

Consequences of falling

The consequences of falling are wide-ranging, interconnected, costly and they may be devastating (Box 20.1).

Box 20.1 Consequences of falling

Fear of falling

This may be associated with a fear of dependency.

Half of the 200 elderly residents interviewed by Sharaf and Ibrahim (2008) had moderate to severe concern about falling, particularly those:

Intervention can decrease these sources of fear. A fear of falls can lead to activity restriction and increase the risk of falls or prompt potential fallers to take extra care. Fear, alongside other factors that restrict activity, should feature in fall-prevention programmes (Lee et al., 2008).

An enduring fear can also affect carers (Liddle & Gilleard, 1995).

Injury

Fall descent, impact and bone strength are important determinants of whether a fall will result in a fracture (Berry & Miller, 2008). Fractured femur is one of the most costly and debilitating consequences of falling. Cummings and Nevitt (1989) hypothesized that four factors increased the likelihood of a fall resulting in a hip fracture:

There is supportive evidence that the ‘nature of the fall’ may determine the type of fracture (Nevitt and Cummings, 1993): elderly women with hip fractures are likely to have fallen ‘sideways or straight down’ and those with wrist fractures are likely to have fallen backward. The pattern of excessive proximal humerus, pelvis and hip fractures in PD suggests that the increased risk is due to specific types of backward or sideways falls (Johnell et al., 1992).

Carer strain/injury

Davey et al. (2004) interviewed 14 spouses of repeat fallers with PD. Most were frightened about their spouse falling; they had received little information about falls, felt unprepared for their role and expressed a need for more support and advice about managing falls. Carers can be injured attempting to prevent falls and helping someone up after a fall: rehabilitation must not overlook them.

Assessing people who have fallen

It would be dangerous not to take a good fall history (with the patient in a safe, stable position) before asking the patient to perform any mobility tests. When, for example, a person who has fallen reports ‘turning is fatal’ or ‘all falls are to do with turning’ (Stack & Ashburn, 1999), the therapist will be suitably alert to the risks inherent in asking that patient to perform a turn test. In the same way that a thorough history from a patient with low back pain should leave the therapist almost able to feel the pain, a thorough history after a fall should leave the therapist almost able to recreate the event in their mind. Some researchers have asked people who have fallen to re-enact the events leading to a fall (for example, Connell & Wolf, 1997), but this is potentially risky and there is no guarantee of a more accurate recall than there is with a verbal account.

Falls are distinct events that happen in a specific time and place and for a specific reason. Although people with neurological conditions fall more frequently than people without, they do not fall continuously. An individual’s risk factors for falling act on them all-day-every-day, but people only fall occasionally, when they cannot preserve their postural stability as they move about their environment. In 1997, Berg et al. wrote that ‘relatively little research has addressed what fallers are actually doing at the time of a fall’. That is changing and we are increasingly illuminating the circumstances in which people (with PD and stroke, at least) fall (Ashburn et al., 2008; Hyndman et al., 2002; Mackintosh et al., 2005; Stack & Ashburn, 1999).

Time spent interviewing the person who has fallen (or a carer or witness) is time well spent, as it will guide intervention. Unfortunately, in the case of inpatient falls, the person documenting the fall may not have witnessed it: Morse et al. (1985) found that staff witnessed only 23% of inpatient falls. While a witness can easily record the location in which they found the faller, the time and evident injuries, they can only surmise what had happened (i.e. the fall-precipitating circumstances).

Interviewing patients and carers

Previous falls are not always well documented in patients’ medical records; patients may not share the same ideas as health-care professionals about what constitutes a fall (e.g. ‘I didn’t fall, I slipped’); nor may they wish to disclose a fall. It is imperative that therapists use all their interviewing skills to talk to patients about previous falls and to probe carefully if a patient denies falling. We strongly disagree with Wild et al. (1981) who claimed that ‘fallers are rarely sufficiently aware of what happened or sufficiently articulate in their description to provide doctors with the necessary information’. The key to understanding what has happened (and thus being able to prevent a repetition) is being able to identify the circumstances in which the individual has fallen.

In other words, the therapist must attempt to discover, through questioning and observation:

Even the act of taking a detailed falls history may be a fall-preventive intervention, boosting insight and confidence. Elderly people who reflect on their falls and seek understanding are better able (than are their non-reflecting peers) to develop strategies to prevent future falls, face their fear of falling and remain active (Roe et al., 2008). Self-reported impaired balance is a readily assessed risk factor for future fractures in elderly people (Wagner et al., 2009). On completion of the interview, refer patients to other specialists if their input is necessary.

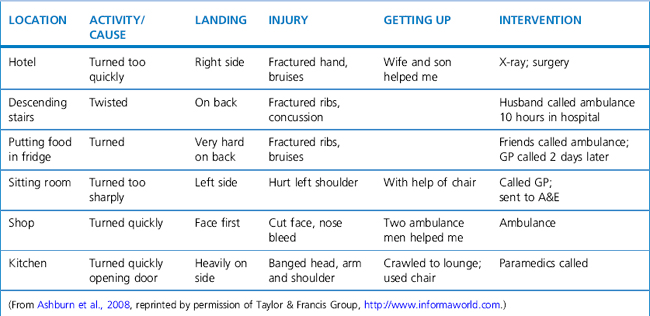

Falls diaries

The same questions that one might ask a patient directly can form the basis of a falls diary. Research participants often complete diaries, sometimes for several months. In a recent study (Ashburn et al., 2008), repeated fallers with PD recorded the circumstances in which they fell over a 6-month period. On a calendar sheet, they marked any day on which they had a fall or a near-miss. On separate dated sheets, they noted where they fell, the suspected cause, what they were doing at the time, how they landed and what happened next. The example diary entries in Table 20.1 outline some injurious falls in which turning was the fall-related activity.

Table 20.1 Examples of injurious falls during turning requiring health service input: an example of falls diary use

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree