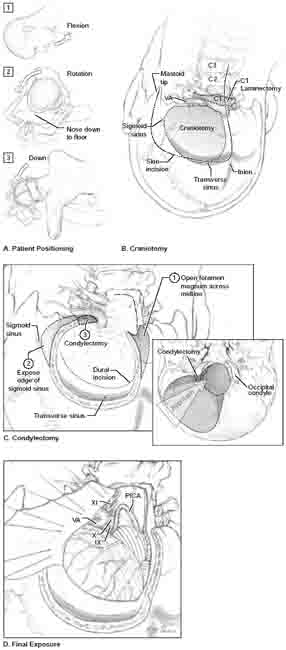

13 Far-Lateral Approach The far-lateral approach is also called the lateral suboccipital approach, the extreme lateral approach, and the extreme lateral inferior transcondylar exposure (ELITE). A modified park-bench or three-quarter prone position is used with the patient placed with the lesion side upward (Fig. 13.1A). The operating table is extended by placing a 3/4-inch-thick plastic board under the mattress and pulling both the mattress and board 6 inches beyond the edge of the table. This extender creates a gap between the Mayfield head holder and its attachment to the table, allowing the dependent arm to hang comfortably over the extended end of the table, cradled in a padded sling. By dropping the patient’s arm and shoulder down, the head can be rotated effectively into position. This position minimizes brachial plexus compression and improves venous return compared with the full prone position. Three maneuvers position the head optimally: flexion in the anteroposterior plane until the chin is one finger’s breadth from the sternum; rotation of 45 degrees away from the side of the lesion, bringing the nose down toward the floor; and lateral flexion 30 degrees down toward the floor. These maneuvers position the clivus perpendicular to the floor, allowing the neurosurgeon to look down the axis of the vertebral and basilar arteries and to work between the lower cranial nerves. The ipsilateral mastoid process becomes the highest point in the operative field, and the posterior cervical-suboccipital angle is opened maximally to increase the neurosurgeon’s operating space. The patient’s up shoulder is taped to keep the cervical-suboccipital angle open. A “hockey-stick” incision is made beginning in the cervical midline over the C4 spinous process (Fig. 13.1B). It extends cephalad to the inion, courses laterally along the superior nuchal line to the mastoid bone, and finishes inferiorly at the mastoid tip. A cut just below the superior nuchal line is made, paralleling the superior nuchal line and leaving a 1-cm cuff of fascia to reattach the muscle during closure. The midline nuchal ligament is identified by continuing this cut across the midline and inspecting the suboccipital muscles. The paraspinous musculature is split in this avascular plane of the nuchal ligament. The cut just below the superior nuchal line extends laterally to the mastoid bone and inferiorly to its tip, detaching the paraspinous muscles. The myocutaneous flap is then mobilized inferolaterally to expose the occipital bone and foramen magnum. Mobilization of the paraspinous musculature in this manner provides adequate exposure of the lateral foramen magnum; the muscles need not be dissected or transected, thereby eliminating a significant source of postoperative pain. Retraction of soft tissue is facilitated by exposure down to and around the C2 spinous process. The vertebral artery (VA) is identified and protected as it courses from the transverse foramen of the lateral mass of C1, through the sulcus arteriosus of the C1 vertebral arch, to its dural entry point. The lateral epidural venous plexus can cause troublesome bleeding and is best preserved by blunt dissection. Bone removal consists of three parts: C1 laminotomy, lateral occipital craniotomy, and condylectomy (Fig. 13.1B). The arch of C1 is removed with the drill, making a cut just medial to the sulcus arteriosus and another across the contralateral arch. These cuts are made in a rostral-to-caudal direction to keep any lurching of the drill away from the VA. Additional atlantal bone can be removed under the VA laterally to the transverse foramen. The foramen can be opened dorsally and the artery mobilized, but this maneuver is rarely needed for intradural aneurysms. Dural adhesions around the foramen magnum are stripped with angled curettes, and a craniotomy is performed using the lip of the foramen magnum as the epidural access for the drill. A suboccipital craniotomy is extended unilaterally from the foramen magnum in the midline, up to the muscle cuff at the level of the transverse sinus, as far laterally as possible, and then back around to the foramen magnum. In elderly patients with adherent dura, a suboccipital bur hole with subsequent cuts down to the foramen magnum may help to preserve dura. The rim of the foramen magnum is rongeured to extend the opening across the midline and laterally toward the occipital condyle (Fig. 13.1C).

Position

Position

Incision and Extracranial Dissection

Incision and Extracranial Dissection

Craniotomy

Craniotomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree