Feeding and Eating Disorders

15.1 Anorexia Nervosa

15.1 Anorexia Nervosa

The term anorexia nervosa is derived from the Greek term for “loss of appetite” and a Latin word implying nervous origin. Anorexia nervosa is a syndrome characterized by three essential criteria. The first is a self-induced starvation to a significant degree—a behavior. The second is a relentless drive for thinness or a morbid fear of fatness—a psychopathology. The third criterion is the presence of medical signs and symptoms resulting from starvation—a physiological symptomatology. Anorexia nervosa is often, but not always, associated with disturbances of body image, the perception that one is distressingly large despite obvious medical starvation. The distortion of body image is disturbing when present, but not pathognomic, invariable, or required for diagnosis. Two subtypes of anorexia nervosa exist: restricting and binge/purge. The theme in all anorexia nervosa subtypes is the highly disproportionate emphasis placed on thinness as a vital source, sometimes the only source, of self-esteem, with weight, and to a lesser degree, shape, becoming the overriding and consuming daylong preoccupation of thoughts, mood, and behaviors.

Approximately half of anorexic persons will lose weight by drastically reducing their total food intake. The other half of these patients will not only diet but will also regularly engage in binge eating followed by purging behaviors. Some patients routinely purge after eating small amounts of food. Anorexia nervosa is much more prevalent in females than in males and usually has its onset in adolescence. Hypotheses of an underlying psychological disturbance in young women with the disorder include conflicts surrounding the transition from girlhood to womanhood. Psychological issues related to feelings of helplessness and difficulty establishing autonomy have also been suggested as contributing to the development of the disorder. Bulimic symptoms can occur as a separate disorder (bulimia nervosa, which is discussed in Section 15.2) or as part of anorexia nervosa. Persons with either disorder are excessively preoccupied with weight, food, and body shape. The outcome of anorexia nervosa varies from spontaneous recovery to a waxing and waning course to death.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Anorexia nervosa has been reported more frequently over the past several decades, with increasing reports of the disorder in prepubertal girls and in boys. The most common ages of onset of anorexia nervosa are the midteens, but up to 5 percent of anorectic patients have the onset of the disorder in their early 20s. The most common age of onset is between 14 and 18 years. Anorexia nervosa is estimated to occur in about 0.5 to 1 percent of adolescent girls. It occurs 10 to 20 times more often in females than in males. The prevalence of young women with some symptoms of anorexia nervosa who do not meet the diagnostic criteria is estimated to be close to 5 percent. Although the disorder was initially reported most often among the upper classes, recent epidemiological surveys do not show that distribution. It seems to be most frequent in developed countries, and it may be seen with greatest frequency among young women in professions that require thinness, such as modeling and ballet.

COMORBIDITY

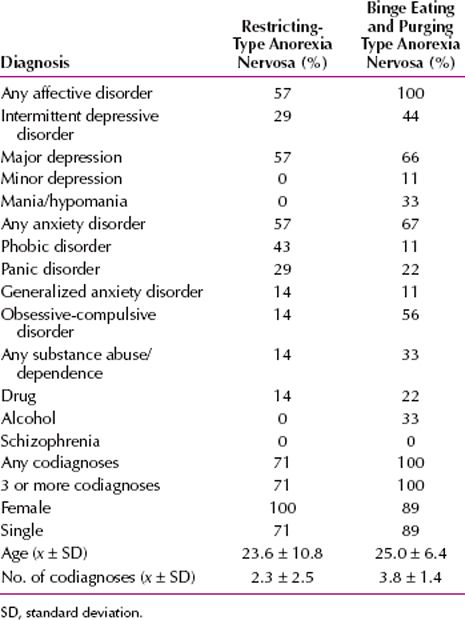

Table 15.1-1 lists comorbid psychiatric conditions associated with anorexia nervosa. Overall, anorexia nervosa is associated with depression in 65 percent of cases, social phobia in 35 percent of cases, and obsessive-compulsive disorder in 25 percent of cases.

Table 15.1-1

Table 15.1-1

Comorbid Psychiatric Conditions Associated with Anorexia Nervosa

ETIOLOGY

Biological, social, and psychological factors are implicated in the causes of anorexia nervosa. Some evidence points to higher concordance rates in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins. Sisters of patients with anorexia nervosa are likely to be afflicted, but this association may reflect social influences more than genetic factors. Major mood disorders are more common in family members than in the general population. Neurochemically, diminished norepinephrine turnover and activity are suggested by reduced 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) levels in the urine and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of some patients with anorexia nervosa. An inverse relation is seen between MHPG and depression in these patients; an increase in MHPG is associated with a decrease in depression.

Biological Factors

Endogenous opioids may contribute to the denial of hunger in patients with anorexia nervosa. Preliminary studies show dramatic weight gains in some patients who are given opiate antagonists. Starvation results in many biochemical changes, some of which are also present in depression, such as hypercortisolemia and nonsuppression by dexamethasone. Thyroid function is suppressed as well. These abnormalities are corrected by realimentation. Starvation may produce amenorrhea, which reflects lowered hormonal levels (luteinizing, follicle-stimulating, and gonadotropin-releasing hormones). Some patients with anorexia nervosa, however, may become amenorrheic before significant weight loss. Several computed tomographic (CT) studies reveal enlarged CSF spaces (enlarged sulci and ventricles) in anorectic patients during starvation, a finding that is reversed by weight gain. In one positron emission tomographic (PET) scan study, caudate nucleus metabolism was higher in the anorectic state than after realimentation.

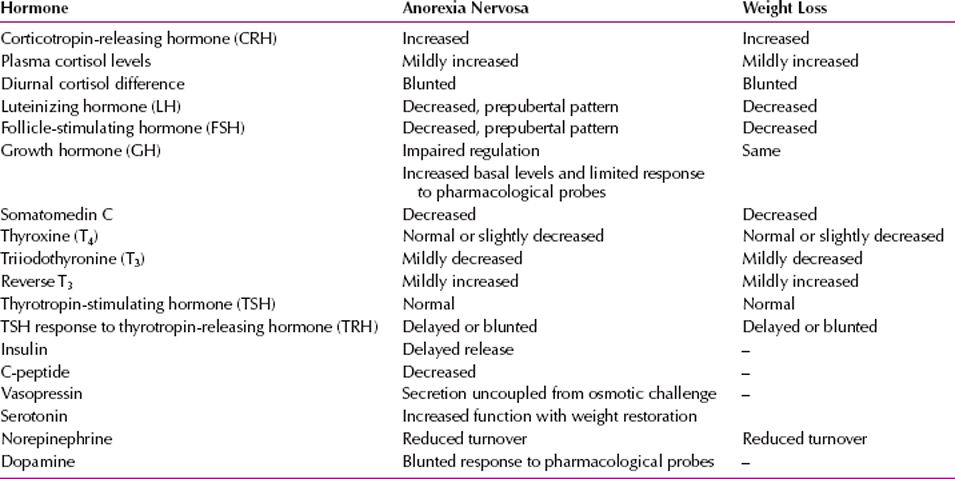

Some authors have proposed a hypothalamic-pituitary axis (neuroendocrine) dysfunction. Some studies have shown evidence for dysfunction in serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, three neurotransmitters involved in regulating eating behavior in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Other humoral factors that may be involved include corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), neuropeptide Y, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, and thyroid-stimulating hormone. Table 15.1-2 lists the neuroendocrine changes associated with anorexia nervosa.

Table 15.1-2

Table 15.1-2

Neuroendocrine Changes in Anorexia Nervosa and Experimental Starvation

Social Factors

Patients with anorexia nervosa find support for their practices in society’s emphasis on thinness and exercise. No family constellations are specific to anorexia nervosa, but some evidence indicates that these patients have close, but troubled, relationships with their parents. Families of children who present with eating disorders, especially binge eating or purging subtypes, may exhibit high levels of hostility, chaos, and isolation and low levels of nurturance and empathy. An adolescent with a severe eating disorder may tend to draw attention away from strained marital relationships.

Vocational and avocational interests interact with other vulnerability factors to increase the probability of developing eating disorders. In young women, participation in strict ballet schools increases the probability of developing anorexia nervosa at least sevenfold. In high school boys, wrestling is associated with a prevalence of full or partial eating-disorder syndromes during wrestling season of approximately 17 percent, with a minority developing an eating disorder and not improving spontaneously at the end of training. Although these athletic activities probably select for perfectionistic and persevering youth in the first place, pressures regarding weight and shape generated in these social milieus reinforce the likelihood that these predisposing factors will be channeled toward eating disorders.

A gay orientation in men is a proved predisposing factor, not because of sexual orientation or sexual behavior per se, but because norms for slimness, albeit muscular slimness, are very strong in the gay community, only slightly lower than for heterosexual women. In contrast, a lesbian orientation may be slightly protective, because lesbian communities may be more tolerant of higher weights and a more normative natural distribution of body shapes than their heterosexual female counterparts.

Psychological and Psychodynamic Factors

Anorexia nervosa appears to be a reaction to the demand that adolescents behave more independently and increase their social and sexual functioning. Patients with the disorder substitute their preoccupations, which are similar to obsessions, with eating and weight gain for other, normal adolescent pursuits. These patients typically lack a sense of autonomy and selfhood. Many experience their bodies as somehow under the control of their parents, so that self-starvation may be an effort to gain validation as a unique and special person. Only through acts of extraordinary self-discipline can an anorectic patient develop a sense of autonomy and selfhood.

Psychoanalytic clinicians who treat patients with anorexia nervosa generally agree that these young patients have been unable to separate psychologically from their mothers. The body may be perceived as though it were inhabited by the introject of an intrusive and unempathic mother. Starvation may unconsciously mean arresting the growth of this intrusive internal object and thereby destroying it. Often, a projective identification process is involved in the interactions between the patient and the patient’s family. Many anorectic patients feel that oral desires are greedy and unacceptable; therefore, these desires are projectively disavowed. Other theories have focused on fantasies of oral impregnation. Parents respond to the refusal to eat by becoming frantic about whether the patient is actually eating. The patient can then view the parents as the ones who have unacceptable desires and can projectively disavow them; that is, others may be voracious and ruled by desire but not the patient.

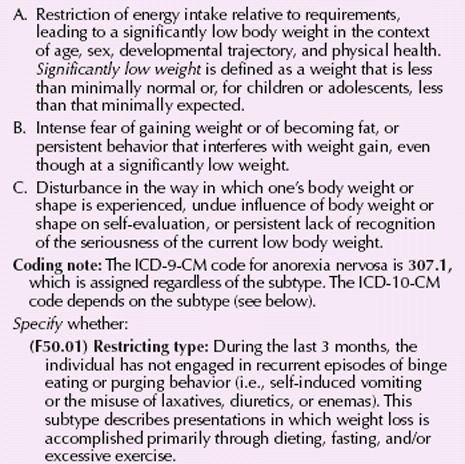

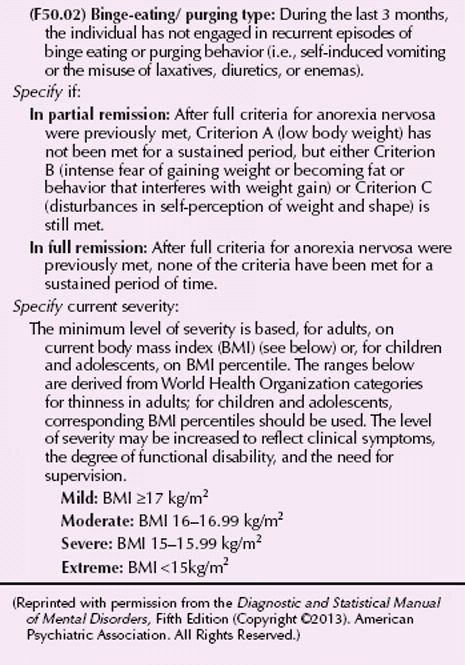

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

The onset of anorexia nervosa usually occurs between the ages of 10 and 30 years. It is present when (1) an individual voluntarily reduces and maintains an unhealthy degree of weight loss or fails to gain weight proportional to growth; (2) an individual experiences an intense fear of becoming fat, has a relentless drive for thinness despite obvious medical starvation, or both; (3) an individual experiences significant starvation-related medical symptomatology, often, but not exclusively, abnormal reproductive hormone functioning, but also hypothermia, bradycardia, orthostasis, and severely reduced body fat stores; and (4) the behaviors and psychopathology are present for at least 3 months. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa are given in Table 15.1-3.

Table 15.1-3

Table 15.1-3

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa

An intense fear of gaining weight and becoming obese is present in all patients with the disorder and undoubtedly contributes to their lack of interest in, and even resistance to, therapy. Most aberrant behavior directed toward losing weight occurs in secret. Patients with anorexia nervosa usually refuse to eat with their families or in public places. They lose weight by drastically reducing their total food intake, with a disproportionate decrease in high-carbohydrate and fatty foods.

As mentioned, the term anorexia is a misnomer, because loss of appetite is usually rare until late in the disorder. Evidence that patients are constantly thinking about food is their passion for collecting recipes and for preparing elaborate meals for others. Some patients cannot continuously control their voluntary restriction of food intake and so have eating binges. These binges usually occur secretly and often at night and are frequently followed by self-induced vomiting. Patients abuse laxatives and even diuretics to lose weight, and ritualistic exercising, extensive cycling, walking, jogging, and running are common activities.

Patients with the disorder exhibit peculiar behavior about food. They hide food all over the house and frequently carry large quantities of candies in their pockets and purses. While eating meals, they try to dispose of food in their napkins or hide it in their pockets. They cut their meat into very small pieces and spend a great deal of time rearranging the pieces on their plates. If the patients are confronted with their peculiar behavior, they often deny that their behavior is unusual or flatly refuse to discuss it.

Obsessive-compulsive behavior, depression, and anxiety are other psychiatric symptoms of anorexia nervosa most frequently noted clinically. Patients tend to be rigid and perfectionist, and somatic complaints, especially epigastric discomfort, are usual. Compulsive stealing, usually of candies and laxatives but occasionally of clothes and other items, may occur.

Poor sexual adjustment is frequently described in patients with the disorder. Many adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa have delayed psychosocial sexual development; in adults, a markedly decreased interest in sex often accompanies onset of the disorder. A minority of anorexic patients has a premorbid history of promiscuity, substance abuse, or both but during the disorder show a decreased interest in sex.

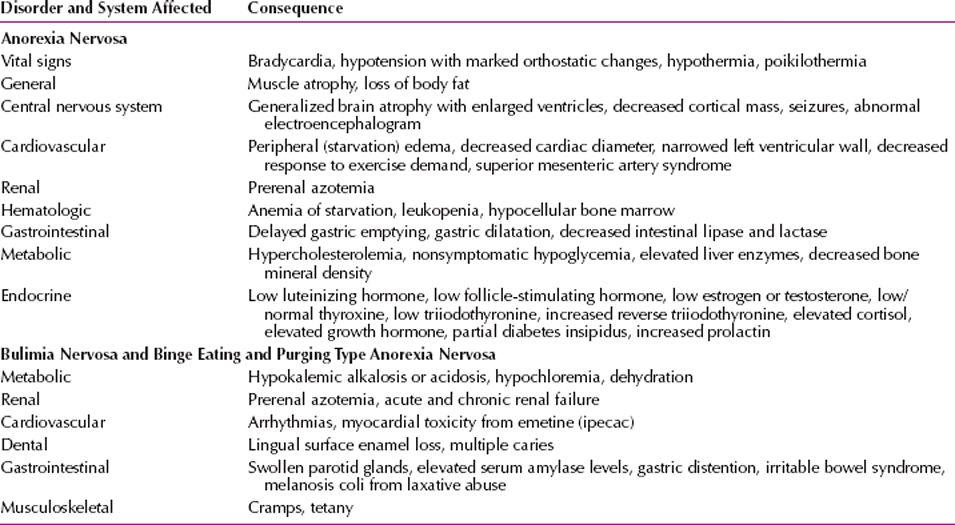

Patients usually come to medical attention when their weight loss becomes apparent. As the weight loss grows profound, physical signs such as hypothermia (as low as 35°C), dependent edema, bradycardia, hypotension, and lanugo (the appearance of neonatal-like hair) appear, and patients show a variety of metabolic changes (Fig. 15.1-1). Some female patients with anorexia nervosa come to medical attention because of amenorrhea, which often appears before their weight loss is noticeable. Some patients induce vomiting or abuse purgatives and diuretics; such behavior causes concern about hypokalemic alkalosis. Impaired water diuresis may be noted.

FIGURE 15.1-1

A patient with anorexia nervosa. (Courtesy of Katherine Halmi, M.D.)

Electrocardiographic (ECG) changes, such as T wave flattening or inversion, ST segment depression, and lengthening of the QT interval, have been noted in the emaciated stage of anorexia nervosa. ECG changes may also result from potassium loss, which can lead to death. Gastric dilation is a rare complication of anorexia nervosa. In some patients, aortography has shown a superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Other medical complications of eating disorders are listed in Table 15.1-4.

Table 15.1-4

Table 15.1-4

Medical Complications of Eating Disorders

SUBTYPES

Anorexia nervosa has been divided into two clinical subtypes: the food-restricting category and the purging category. In the food-restricting category, present in approximately 50 percent of cases, food intake is highly restricted (usually with attempts to consume fewer than 300 to 500 calories per day and no fat grams), and the patient may be relentlessly and compulsively overactive, with overuse athletic injuries. In the purging subtype, patients alternate attempts at rigorous dieting with intermittent binge or purge episodes. Purging represents a secondary compensation for the unwanted calories, most often accomplished by self-induced vomiting, frequently by laxative abuse, less frequently by diuretics, and occasionally with emetics. Sometimes, repetitive purging occurs without prior binge eating, after ingesting only relatively few calories. Both types may be socially isolated and have depressive disorder symptoms and diminished sexual interest. Overexercising and perfectionistic traits are also common in both types.

A new diagnostic category in DSM-5 is binge eating disorder (see Section 15.3) characterized by episodic bouts of the intake of excessive amounts of food but without purging or similar compensatory behavior.

Those who practice binge eating and purging share many features with persons who have bulimia nervosa without anorexia nervosa. Those who binge eat and purge tend to have families in which some members are obese, and they themselves have histories of heavier body weights before the disorder than do persons with the restricting type. Binge eating–purging persons are likely to be associated with substance abuse, impulse control disorders, and personality disorders. Persons with restricting anorexia nervosa often have obsessive-compulsive traits with respect to food and other matters. Some persons with anorexia nervosa may purge but not binge.

Persons with anorexia nervosa have high rates of comorbid major depressive disorders; major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder has been reported in up to 50 percent of patients with anorexia nervosa. The suicide rate is higher in persons with the binge eating–purging type of anorexia nervosa than in those with the restricting type.

Patients with anorexia nervosa are often secretive, deny their symptoms, and resist treatment. In almost all cases, relatives or intimate acquaintances must confirm a patient’s history. The mental status examination usually shows a patient who is alert and knowledgeable on the subject of nutrition and who is preoccupied with food and weight.

A patient must have a thorough general physical and neurological examination. If the patient is vomiting, a hypokalemic alkalosis may be present. Because most patients are dehydrated, serum electrolyte levels must be determined initially and periodically. Hospitalization may be necessary to deal with medical complications.

A young woman who weighed 10 percent above the average weight but was otherwise healthy, functioning well, and working hard as a university student joined a track team, started training for hours a day, more than her teammates, began to perceive herself as fat and thought that her performance would be enhanced if she lost weight. She started to diet and reduced her weight to 87 percent of the “ideal weight” for her age according to standard tables. At her point of maximum weight loss, her performance actually declined, and she pushed herself even harder in her training regimen. She started to feel apathetic and morbidly afraid of becoming fat. Her food intake became restricted and she stopped eating anything containing fat. Her menstrual periods became skimpy and infrequent but did not cease. (Courtesy of Arnold E. Andersen, M.D., and Joel Yager, M.D.)

PATHOLOGY AND LABORATORY EXAMINATION

A complete blood count often reveals leukopenia with a relative lymphocytosis in emaciated patients with anorexia nervosa. If binge eating and purging are present, serum electrolyte determination reveals hypokalemic alkalosis. Fasting serum glucose concentrations are often low during the emaciated phase, and serum salivary amylase concentrations are often elevated if the patient is vomiting. The ECG may show ST segment and T-wave changes, which are usually secondary to electrolyte disturbances; emaciated patients have hypotension and bradycardia. Young girls may have a high serum cholesterol level. All these values revert to normal with nutritional rehabilitation and cessation of purging behaviors. Endocrine changes that may occur, such as amenorrhea, mild hypothyroidism, and hypersecretion of corticotrophin-releasing hormone, are caused by the underweight condition and revert to normal with weight gain.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of anorexia nervosa is complicated by patients’ denial of the symptoms, the secrecy surrounding their bizarre eating rituals, and their resistance to seeking treatment. Thus, it may be difficult to identify the mechanism of weight loss and the patient’s associated ruminative thoughts about distortions of body image.

Clinicians must ascertain that a patient does not have a medical illness that can account for the weight loss (e.g., a brain tumor or cancer). Weight loss, peculiar eating behaviors, and vomiting can occur in several mental disorders. Depressive disorders and anorexia nervosa have several features in common, such as depressed feelings, crying spells, sleep disturbance, obsessive ruminations, and occasional suicidal thoughts. The two disorders, however, have several distinguishing features. Generally, a patient with a depressive disorder has decreased appetite, whereas a patient with anorexia nervosa claims to have normal appetite and to feel hungry; only in the severe stages of anorexia nervosa do patients actually have decreased appetite. In contrast to depressive agitation, the hyperactivity seen in anorexia nervosa is planned and ritualistic. The preoccupation with recipes, the caloric content of foods, and the preparation of gourmet feasts is typical of patients with anorexia nervosa but is absent in patients with a depressive disorder. In depressive disorders, patients have no intense fear of obesity or disturbance of body image.

Weight fluctuations, vomiting, and peculiar food handling may occur in somatization disorder. On rare occasions, a patient fulfills the diagnostic criteria for both somatization disorder and anorexia nervosa; in such a case, both diagnoses should be made. Generally, the weight loss in somatization disorder is not as severe as that in anorexia nervosa, nor does a patient with somatization disorder express a morbid fear of becoming overweight, as is common in those with anorexia nervosa. Amenorrhea for 3 months or longer is unusual in somatization disorder.

In patients with schizophrenia, delusions about food are seldom concerned with caloric content. More likely, they believe the food to be poisoned. Patients with schizophrenia are rarely preoccupied with a fear of becoming obese and do not have the hyperactivity that is seen in patients with anorexia nervosa. Patients with schizophrenia have bizarre eating habits but not the entire syndrome of anorexia nervosa.

Anorexia nervosa must be differentiated from bulimia nervosa, a disorder in which episodic binge eating, followed by depressive moods, self-deprecating thoughts, and self-induced vomiting occur while patients maintain their weight within a normal range. Patients with bulimia nervosa seldom lose 15 percent of their weight, but the two conditions frequently coexist.

Rare conditions of unknown etiology are seen in which hyperactivity of the vagus nerve causes changes in eating patterns that are associated with weight loss, sometimes of severe degree. In such cases bradycardia, hypotension, and other parasympathomimetic signs and symptoms are seen. Because the vagus nerve relates to the enteric nervous system, eating may be associated with gastric distress such as nausea or bloating. Patients do not generally lose their appetite. Treatment is symptomatic and anticholinergic drugs can reverse hypotension and bradycardia, which may be life-threatening.

COURSE AND PROGNOSIS

The course of anorexia nervosa varies greatly—spontaneous recovery without treatment, recovery after a variety of treatments, a fluctuating course of weight gains followed by relapses, and a gradually deteriorating course resulting in death caused by complications of starvation. One study reviewing subtypes of anorectic patients found that restricting-type anorectic patients seemed less likely to recover than those of the binge eating–purging type. The short-term response of patients to almost all hospital treatment programs is good. Those who have regained sufficient weight, however, often continue their preoccupation with food and body weight, have poor social relationships, and exhibit depression. In general, the prognosis is not good. Studies have shown a range of mortality rates from 5 to 18 percent.

Indicators of a favorable outcome are admission of hunger, lessening of denial and immaturity, and improved self-esteem. Such factors as childhood neuroticism, parental conflict, bulimia nervosa, vomiting, laxative abuse, and various behavioral manifestations (e.g., obsessive-compulsive, hysterical, depressive, psychosomatic, neurotic, and denial symptoms) have been related to poor outcome in some studies, but not in others.

Ten-year outcome studies in the United States have shown that about one fourth of patients recover completely and another one half are markedly improved and functioning fairly well. The other one fourth includes an overall 7 percent mortality rate and those who are functioning poorly with a chronic underweight condition. Swedish and English studies over a 20- and 30-year period show a mortality rate of 18 percent. About half of patients with anorexia nervosa eventually will have the symptoms of bulimia, usually within the first year after the onset of anorexia nervosa.

TREATMENT

In view of the complicated psychological and medical implications of anorexia nervosa, a comprehensive treatment plan, including hospitalization when necessary and both individual and family therapy, is recommended. Behavioral, interpersonal, and cognitive approaches are used and, in many cases, medication may be indicated.

Hospitalization

The first consideration in the treatment of anorexia nervosa is to restore patients’ nutritional state; dehydration, starvation, and electrolyte imbalances can seriously compromise health and, in some cases, lead to death. The decision to hospitalize a patient is based on the patient’s medical condition and the amount of structure needed to ensure patient cooperation. In general, patients with anorexia nervosa who are 20 percent below the expected weight for their height are recommended for inpatient programs, and patients who are 30 percent below their expected weight require psychiatric hospitalization for 2 to 6 months.

Inpatient psychiatric programs for patients with anorexia nervosa generally use a combination of a behavioral management approach, individual psychotherapy, family education and therapy, and, in some cases, psychotropic medications. Successful treatment is promoted by the ability of staff members to maintain a firm yet supportive approach to patients, often through a combination of positive reinforcers (praise) and negative reinforcers (restriction of exercise). The program must have some flexibility for individualizing treatment to meet patients’ needs and cognitive abilities. Patients must become willing participants for treatment to succeed in the long run.

Most patients are uninterested in psychiatric treatment and even resist it; they are brought to a doctor’s office unwillingly by agonizing relatives or friends. The patients rarely accept the recommendation of hospitalization without arguing and criticizing the proposed program. Emphasizing the benefits, such as relief of insomnia and depressive signs and symptoms, may help persuade the patients to admit themselves willingly to the hospital. Relatives’ support and confidence in the physicians and treatment team are essential when firm recommendations must be carried out. Patients’ families should be warned that the patients will resist admission and, for the first several weeks of treatment, will make many dramatic pleas for their families’ support to obtain release from the hospital program. Compulsory admission or commitment should be obtained only when the risk of death from the complications of malnutrition is likely. On rare occasions, patients prove that the doctor’s statements about the probable failure of outpatient treatment are wrong. They may gain a specified amount of weight by the time of each outpatient visit, but such behavior is uncommon, and a period of inpatient care is usually necessary.

Hospital Management. The following considerations apply to the general management of patients with anorexia nervosa during a hospitalized treatment program. Patients should be weighed daily, early in the morning after emptying the bladder. The daily fluid intake and urine output should be recorded. If vomiting is occurring, hospital staff members must monitor serum electrolyte levels regularly and watch for the development of hypokalemia. Because food is often regurgitated after meals, the staff may be able to control vomiting by making the bathroom inaccessible for at least 2 hours after meals or by having an attendant in the bathroom to prevent the opportunity for vomiting. Constipation in these patients is relieved when they begin to eat normally. Stool softeners may occasionally be given, but never laxatives. If diarrhea occurs, it usually means that patients are surreptitiously taking laxatives. Because of the rare complication of stomach dilation and the possibility of circulatory overload when patients immediately start eating an enormous number of calories, the hospital staff should give patients about 500 calories over the amount required to maintain their present weight (usually 1,500 to 2,000 calories a day). It is wise to give these calories in six equal feedings throughout the day, so that patients need not eat a large amount of food at one sitting. Giving patients a liquid food supplement such as Sustagen may be advisable, because they may be less apprehensive about gaining weight slowly with the formula than by eating food. After patients are discharged from the hospital, clinicians usually find it necessary to continue outpatient supervision of the problems identified in the patients and their families.

Psychotherapy

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. Cognitive and behavioral therapy principles can be applied in both inpatient and outpatient settings and have been found effective for inducing weight gain. Monitoring is an essential component of cognitive-behavioral therapy. Patients are taught to monitor their food intake, their feelings and emotions, their binging and purging behaviors, and their problems in interpersonal relationships. Patients are taught cognitive restructuring to identify automatic thoughts and to challenge their core beliefs. Problem solving is a specific method whereby patients learn how to think through and devise strategies to cope with their food-related and interpersonal problems. Patients’ vulnerability to rely on anorectic behavior as a means of coping can be addressed if they can learn to use these techniques effectively.

Dynamic Psychotherapy. Dynamic expressive-supportive psychotherapy is sometimes used in the treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa, but their resistance may make the process difficult and painstaking. Because patients view their symptoms as constituting the core of their specialness, therapists must avoid excessive investment in trying to change their eating behavior. The opening phase of the psychotherapy process must be geared toward building a therapeutic alliance. Patients may experience early interpretations as though someone else were telling them what they really feel and thereby minimizing and invalidating their own experiences. Therapists who empathize with patients’ points of view and take an active interest in what their patients think and feel, however, convey to patients that their autonomy is respected. Above all, psychotherapists must be flexible, persistent, and durable in the face of patients’ tendencies to defeat any efforts to help them.

Family Therapy. A family analysis should be done for all patients with anorexia nervosa who are living with their families, which is used as a basis for a clinical judgment on what type of family therapy or counseling is advisable. In some cases, family therapy is not possible; however, issues of family relationships can then be addressed in individual therapy. Sometimes, brief counseling sessions with immediate family members is the extent of family therapy required. In one controlled family therapy study in London, anorectic patients under the age of 18 benefited from family therapy, whereas patients over the age of 18 did worse in family therapy than with the control therapy. No controlled studies have been reported on the combination of individual and family therapy; however, in actual practice, most clinicians provide individual therapy and some form of family counseling in managing patients with anorexia nervosa.

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacological studies have not yet identified any medication that yields definitive improvement of the core symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Some reports support the use of cyproheptadine (Periactin), a drug with antihistaminic and antiserotonergic properties, for patients with the restricting type of anorexia nervosa. Amitriptyline (Elavil) has also been reported to have some benefit. Other medications that have been tried by patients with anorexia nervosa with variable results include clomipramine (Anafranil), pimozide (Orap), and chlorpromazine (Thorazine). Trials of fluoxetine (Prozac) have resulted in some reports of weight gain, and serotonergic agents may yield positive responses in some cases. In patients with anorexia nervosa and coexisting depressive disorders, the depressive condition should be treated. Concern exists about the use of tricyclic drugs in low-weight, depressed patients with anorexia nervosa, who may be vulnerable to hypotension, cardiac arrhythmia, and dehydration. Once an adequate nutritional status has been attained, the risk of serious adverse effects from the tricyclic drugs may decrease; in some patients, the depression improves with weight gain and normalized nutritional status.

REFERENCES

Andersen AE, Yager J. Eating disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:2128.

Birmingham CL, Treasure J. Medical Management of Eating Disorders. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Blechert J, Ansorge U, Tuschen-Caffier B. A body-related dot-probe task reveals distinct attentional patterns for bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:575.

Brown LM, Clegg DJ. Estrogen and leptin regulation of endocrinological features of anorexia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacol Rev. 2013;38:237.

Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Crow S, Peterson CB, Le Grange D, Simonich HK, Cao L, Lavender JM, Gordon KH. The role of affect in the maintenance of anorexia nervosa: Evidence from a naturalistic assessment of momentary behaviors and emotion. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122(3):709–719.

Fallon P, Wisniewski L. A system of evidenced-based techniques and collaborative clinical interventions with a chronically ill patient. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(5):501–506.

Fazeli PK, Misra M, Goldstein M, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Fibroblast growth factor-21 may mediate growth hormone resistance in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:369.

Fladung AK, Grön G, Grammer K, Herrnberger B, Schilly E, Grasteit S, Wolf RC, Walter H, von Wietersheim J. A neural signature of anorexia nervosa in the ventral striatal reward system. Am J Psych. 2009;167:206.

Frank GKW, Reynolds JR, Shott ME, Jappe L, Yang TT, Tregellas JR, O’Reilly RC. Anorexia nervosa and obesity are associated with opposite brain reward response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2031.

Friederich HC, Herzog W. Cognitive-behavioral flexibility in anorexia nervosa. In: Adan RAH, Kaye WH, eds. Behavioral Neurobiology of Eating Disorders. New York: Springer; 2011:111.

Germain N, Galusca B, Grouselle D, Frere D, Billard S, Epelbaum J, Estour B. Ghrelin and obestatin circadian levels differentiate bingeing-purging from restrictive anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3057.

Hay P. A systematic review of evidence for psychological treatments in eating disorders: 2005–2012. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(5):462–469.

Kishi T, Kafantaris V, Sunday S, Sheridan EM, Correll CU. Are antipsychotics effective for the treatment of anorexia nervosa? Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:e757.

Kumar KK, Tung S, Iqbal J. Bone loss in anorexia nervosa: Leptin, serotonin, and the sympathetic nervous system. Ann New York Acad Sci. 2010;1211:51.

Locke J, Grange DL. Treatment Manual for Anorexia Nervosa. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2013.

Lopez C, Davies H, Tchanturia K. Neuropsychological inefficiences in anorexia nervosa targeted in clinical practice: The development of a module of cognitive remediation therapy. In: Fox J, Goss K, eds. Eating and Its Disorders. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2012:185.

Versini A, Ramoz N, Strat YL, Scherag S, Ehrlich S, Boni C, Hinney A, Hebebrand J, Romo L, Guelfi JD, Gorwood P. Estrogen receptor 1 gene (ESR1) is associated with restrictive anorexia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1818.

Zipfel S, et al. Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):127–137.

15.2 Bulimia Nervosa

15.2 Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by episodes of binge eating combined with inappropriate ways of stopping weight gain. Physical discomfort—for example, abdominal pain or nausea—terminates the binge eating, which is often followed by feelings of guilt, depression, or self-disgust. Unlike patients with anorexia nervosa, those with bulimia nervosa typically maintain a normal body weight.

The term bulimia nervosa derives from the terms for “ox-hunger” in Greek and “nervous involvement” in Latin. For some patients, bulimia nervosa may represent a failed attempt at anorexia nervosa, sharing the goal of becoming very thin, but occurring in an individual less able to sustain prolonged semistarvation or severe hunger as consistently as classic restricting anorexia nervosa patients. For others, eating binges represent “breakthrough eating” episodes of giving in to hunger pangs generated by efforts to restrict eating so as to maintain a socially desirable level of thinness. Still others use binge eating as a means to self-medicate during times of emotional distress. Regardless of the reason, eating binges provoke panic as individuals feel that their eating has been out of control. The unwanted binges lead to secondary attempts to avoid the feared weight gain by a variety of compensatory behaviors, such as purging or excessive exercise.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree