Chapter 15 Femoral Nerve

Anatomy

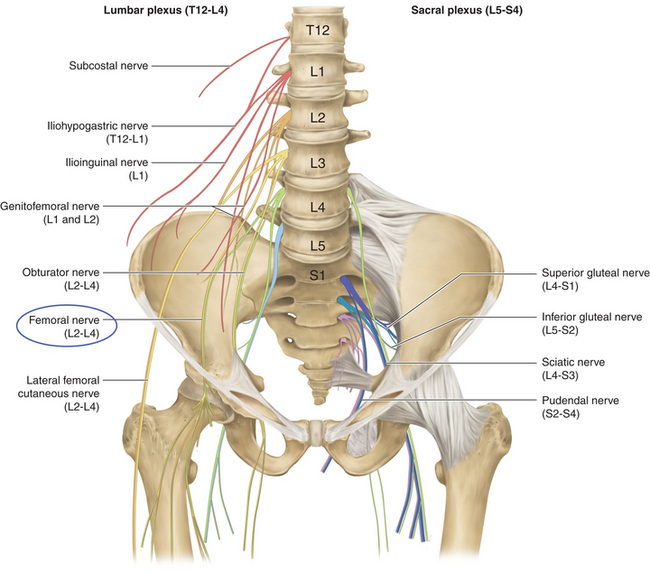

• The femoral nerve arises from the posterior divisions of L2, L3, and L4. The nerve traverses the posterior abdominal wall, passes behind the inguinal ligament, and breaks into motor and sensory branches in the proximal anterior thigh (Figure 15-1).

• The nerve runs behind the fascia that covers the psoas and iliacus muscles. It is found in the gutter between the two muscles.

• The psoas is supplied segmentally, but the iliacus is supplied directly from the femoral nerve. The conjoined tendon of these two muscles is attached to the femur, and they are both strong flexors of the hip joint.

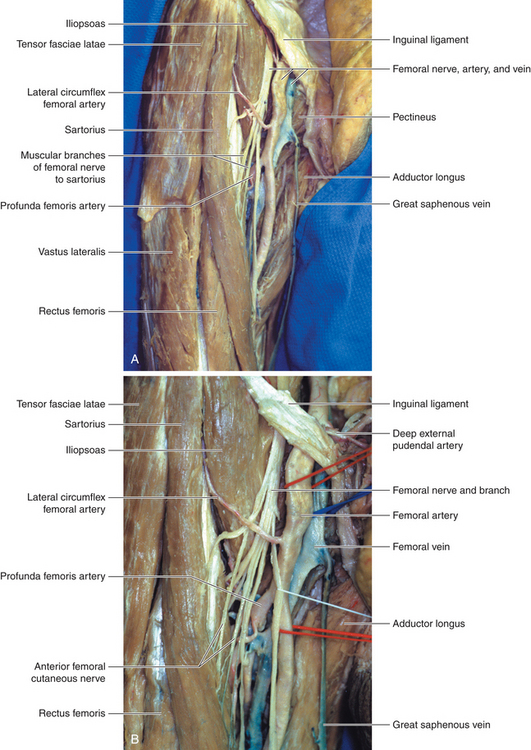

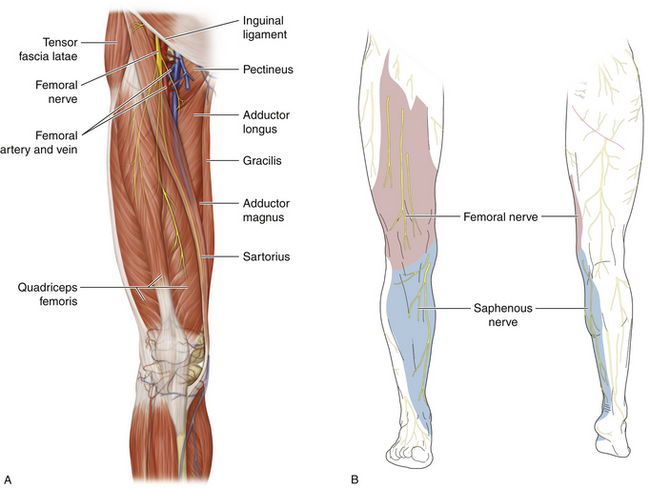

• The substantial, tapelike nerve runs a very short distance in the thigh before it breaks up into sensory and motor branches (Figure 15-2).

• The lateral circumflex artery weaves through the terminal branches of the femoral nerve. The motor branches supplying the various quadriceps muscles lie deep to that artery, as does the saphenous nerve (Figure 15-3).

• The main nerve is an immediate lateral relation of the femoral artery at the groin; however, the nerve is not contained in the femoral sheath (Figure 15-4).

Figure 15-2 A, The femoral nerve in the femoral triangle. B, The femoral nerve’s extensive sensory distribution.

Technique

• The nerve can be exposed either in the abdomen or in the thigh. The two exposures can be joined in appropriate cases (Figure 15-5). In some cases the inguinal ligament is divided over the course of the nerve (Figure 15-6). Alternatively, the surgeon can operate through two exposures and pass grafts from the abdominal exposure to the femoral triangle dissection under the intact inguinal ligament (Figure 15-7).

• A standard muscle-splitting approach is made (similar to an extensive appendectomy incision). The key point is that the incision must be placed sufficiently high so as to enable the surgeon to access L2 when necessary (e.g., for a proximal nerve tumor) (Figure 15-8).

• The peritoneum is not opened, but the peritoneum and extraperitoneal fat are pushed medially and forward by the fingertips of the operator’s hand. The psoas is a substantial muscle, and the surgeon’s fingertips, sliding medially across the iliacus fascia, will bump into the lateral border of the psoas. The surgeon’s fingers must stay firmly on the iliacus fascia so as to be truly in the extraperitoneal space behind the ureter.

• The femoral nerve is easily seen through the fascia, but additional medial retraction of the lateral border of the psoas will be required to display the spinal nerves of origin. Gentle traction of the femoral nerve will help guide the surgeon upward to the L2 spinal nerve if that degree of proximal exposure is required. The surgeon should not mistake the tendon of psoas minor, lying on the anterior surface of the psoas, for the femoral nerve.

• The genitofemoral nerve is of much smaller caliber than the femoral nerve and is located in front of the psoas major.

• If the surgery is aimed at relieving pressure on the femoral nerve by evacuating a clot behind the iliacus fascia, all that is needed is to widely incise the fascia; liquid and clotted blood will immediately extrude into the wound.

• In the thigh, the operator palpates the anterior superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis and can then palpate the pulsating femoral artery, halfway between those points.

• The surgeon may be perplexed at not immediately finding the substantial femoral nerve lateral to the artery. The nerve is not in the femoral sheath and thus must be dissected in its own investing tissue, deep to the fascia lata and lateral to the femoral artery. If the femoral artery is dissected early in the procedure, care must be taken not to unwittingly drive the sharp tips of a self-retaining retractor directly into the femoral nerve.

• The inguinal ligament is sharply cleared, and a retractor, placed under the ligament and superficial to the femoral nerve, will aid in securing a viable proximal stump. If this maneuver fails, then an appropriate proximal stump will have to be defined via the muscle-splitting extraperitoneal approach (Figure 15-9). Similarly, if it is impossible to define a viable distal stump when dealing with an intraabdominal injury, the nerve in the thigh should be exposed. By gently tugging the nerve in the thigh, the surgeon will be guided in the intraabdominal approach.

• Where appropriate, grafts can be placed behind the inguinal ligament, with the proximal sutures placed in the abdomen and the distal sutures placed in the thigh. The grafts should be cut to the appropriate length and passed up or down behind the inguinal ligament as a group (passing individual grafts later will distract the ones that have already been sewn in).

• Injuries in the proximal thigh present a significant problem, as the major branches to the individual quadriceps muscle must be defined. The nerve to vastus medialis is about the same caliber as the saphenous nerve and runs down through the femoral triangle, lateral to the femoral artery. The nerve to vastus lateralis accompanies the descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery. The saphenous nerve is entirely sensory, so grafting into that branch obviously will not restore quadriceps function.

• The sartorius and pectineus muscles are supplied by motor branches anterior to the lateral circumflex artery, but the most important thing is to get motor supply to the large knee extensors—in other words, the quadriceps.

• In practice, it can be difficult to find viable distal stumps of quadriceps motor nerves, and the tedious dissection through scar tissue requires considerable patience.

• In assessing a patient for return of function over the months, the surgeon should not mistake tensing of the iliotibial tract by contraction of the tensor fasciae latae (superior gluteal nerve) and gluteus maximus (inferior gluteal nerve) for quadriceps contraction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree