Diagnostic Considerations

Currently accepted essentials of diagnosis are presented in

Table 19-1. Medical and mental health professionals can screen for FASD. Diagnosis is ideally made by medical professionals working with an interdisciplinary team, because test data and psychosocial information indicating central nervous system (CNS) damage/dysfunction are central to the diagnosis.

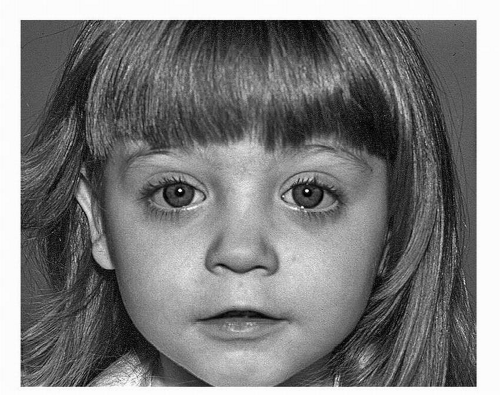

The most obvious manifestation of the developmental effects of prenatal alcohol exposure is the full FAS. FAS is a permanent birth defect syndrome known to be caused by maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy. FAS can be recognized by a pattern of characteristic dysmorphic facial features, smooth philtrum, thin upper lip, short palpebral fissure lengths (

Fig. 19-1), pre- or postnatal growth deficiency, and a variable manifestation of CNS damage/dysfunction. Diagnostic researcher Astley maintains that the specificity of the FAS facial phenotype to prenatal alcohol exposure supports a clinical judgment that the cognitive and behavioral dysfunction observed among individuals with FAS is due, at least in part, to brain damage caused by a teratogen. Studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show FAS rates ranging from 0.2 to 1.5 cases per 1000 live births, comparable to other common developmental disabilities such as Down syndrome or spina bifida.

Prenatal alcohol exposure, however, is also known to cause a wider spectrum of adverse functional outcomes, whether or not the characteristic facial features occur. Over the years, clinicians and researchers have given a variety of labels to those who lack some or all of the physical features of FAS, but still have neurobehavioral deficits presumed to be related to prenatal alcohol exposure. Labels include descriptive terms such as the outdated term “fetal alcohol effects” (FAE), which should no longer be used in clinical or research settings. To label conditions across the spectrum, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended other terms for diagnostic purposes, which are described below. Alcohol-related conditions resulting from prenatal alcohol not meeting the criteria for FAS are believed to occur about three times as often as does FAS, and some have estimated the rates of the full range of FASD to be as high as 9 or 10 per 1000 live births.

Initially, diagnostic emphasis was placed on physical findings, including growth deficiency and the cluster of minor facial anomalies characteristic of the fetal effects of alcohol. But in 2000, researchers Streissguth and O’Malley argued that diagnosis based on facial features is problematic, especially because the FAS face arises from prenatal exposure occurring during only a very short period of vulnerability, and so is quite tied to the timing of prenatal alcohol exposure. In 2005, Chudley and colleagues stated that “in the wide array of FASDs, facial dys-morphology is often absent and, in the final analysis, has little importance compared with the impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on brain function” (

p. 56). More recently, then, there has been increasing diagnostic emphasis on the neurobehavioral deficits presumed to be related to prenatal alcohol exposure, as these are of greater functional significance than the physical features—and are highly associated with caregiver stress, and may be present even when characteristic physical features are not. There has also been a research emphasis on trying to identify a “behavioral phenotype” of FASD, or characteristic profile of learning and behavioral deficits. This line of research is relatively new and challenging. To date, no commonly accepted behavioral phenotype has been described, but increasing evidence reviewed by the researcher Kodituwakku notes generalized deficits in processing complex information.

Diagnostic systems for clinical and epidemiologic settings are under intensive development because of efforts to make diagnosis more accessible and reliable across settings. In 1996, the IOM in the United States defined five conditions along the spectrum with categories of: (1) FAS with confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure; (2) FAS without confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure; (3) partial FAS; (4) alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND); and (5) alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD). The IOM made recommendations that research data be gathered to allow refinement and validation of diagnostic system(s). Since then, national guidelines for diagnosis have been and are now being developed around the world.

Presently, national guidelines for diagnosis of the full FAS exist in the United States, but various systems also exist for diagnosing the full spectrum of FASD in the United States, Canada, and other countries. These various diagnostic systems are being used to define samples in much of the research now accumulating in the field of FASD. Consensus has not yet been reached on a single diagnostic system, although there are many areas of agreement between the systems in common use. Work to clarify diagnostic systems and understanding conditions across the fetal alcohol spectrum is of great importance. It is of clinical, epidemiologic, and research interest to generate accurate diagnoses of individuals, and also to reliably differentiate between meaningful subgroups on the fetal alcohol spectrum. At present, clinicians recognizing only the characteristic facial features of FAS may indeed identify individuals with the full syndrome, but miss the much larger number of individuals (such as those with ARND or partial FAS) actually showing debilitating CNS effects of prenatal alcohol, but not any or all of the facial features.

Clinical Features

Individuals diagnosed with FASD show neurobehavioral deficits across a number of developmental domains, with no “behavioral phenotype” identified at this point in time. In this medical condition, difficulties can occur in cognition and executive function, attention, learning and memory, speech and language, visual—spatial skills, fine and gross motor skills, and/or adaptive behavior. These difficulties impact how the affected individual functions in all life settings, including home activities, school performance, how they get along with peers, and success in employment. Families, researchers, and clinicians believe that neurodevelopmental difficulties are the basis for the behavior and lifestyle problems often seen among those with FASD—and that what are actually difficulties in learning, memory, or behavioral regulation, or a generalized deficit in processing complex information, may often be misinterpreted as oppositional, stubborn, noncompliant, or even antisocial behavior. While there is some research evidence to support these speculations, further studies are needed to draw a firm conclusion. But few would argue that it is the difficulties with behavior that often lead families to seek professional support for their alcohol-affected child, teen, or adult.

Because of the variable way in which alcohol exposure impacts fetal development and causes CNS damage and dysfunction, no two individuals with FASD are alike in clinical features, although they share common areas of likely deficit. These clinical features persist over time, changing their “look” somewhat as individuals grow and mature. It should be noted that children born prenatally alcohol-exposed often have other prenatal exposures, such as to cigarettes or street drugs, and most have some degree of postnatal environmental risk. While animal and longitudinal study of children with moderate levels of alcohol exposure do clearly show that alcohol is a neurobehavioral teratogen, there are certainly other factors associated with adverse developmental outcomes. But prenatal alcohol exposure is a central concern, and FASD is a descriptive and diagnostic term that captures a crucial aspect of the clinical and educational presentation of an affected individual. FASD has some prognostic value, definite implications for treatment and, importantly, may suggest that FASD prevention is needed.

Behavior Problems, Social Skills Deficits, and Psychiatric Conditions

Because individuals with FASD often have challenging behavior, although this may actually arise from underlying neurodevelopmental difficulties, maladaptive behavior is discussed first. While not all individuals with FASD show maladaptive behavior, many children with FASD demonstrate behavior problems and psychiatric disorders, such as attention deficits, depressive and other internalizing disorders, oppositional defiant behavior and conduct disorders, and specific phobias, when compared to typically developing peers. This high prevalence of behavioral difficulties and psychiatric conditions continues into adolescence and adulthood among those with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Social skills deficits are common among children

diagnosed with FASD based on both parent and teacher report. Social skills deficits can include important areas of relationship development such as cooperation, initiation of conversations, making friends, and responding appropriately to conflict situations, all contributing to poor social behavior across multiple settings. Other specific social and behavioral deficits in children with FASD include poor understanding of consequences, temper tantrums and angry outbursts, unpredictable behavior, noncompliance, and difficulty regulating behavior. Other psychosocial difficulties include a higher risk of legal difficulties, alcohol and drug abuse, and other maladaptive behaviors, compared to typically developing peers.

Psychiatric and behavior problems occur in individuals across the spectrum of FASD, and not just among those diagnosed with FAS. These problems persist across time, and appear at a greater rate than would be expected based on the presence of cognitive deficits or environmental factors. Individuals with conditions on the wider fetal alcohol spectrum may actually have more debilitating behavior and lifestyle problems than those with the full FAS, perhaps because their problems go unrecognized or are inappropriately treated. These social and behavioral deficits affect an individual’s function in all life settings, and likely arise in a large part from underlying global or complex neurobehavioral deficits resulting from the teratogenic effects of prenatal alcohol exposure. Because the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure are contingent upon multiple maternal and fetus factors, and on dosage patterns, damage to the developing fetus can be widespread and diffuse. The impact on CNS structure and function is variable from person to person, making treatment quite complex and necessarily individualized.

There is no clear consensus about how FASD is acknowledged in current psychiatric or medical diagnostic coding schemes. Some consider FASD a medical condition that modifies the presentation of other psychiatric conditions. Some advocate other strategies for denoting that prenatal alcohol exposure, or clinical effects like FASD, as part of how a child’s situation is conceptualized. There is a specific code in the current medical coding system (ICD-9-CM: 760.71) used for general medical conditions that is utilized both for the full “FAS” and for “toxic effects of alcohol,” and there are other codes that might be used depending on a clinician’s case formulation. But the wider fetal alcohol spectrum and the lifelong aspect of this disorder are not adequately dealt with in psychiatric, medical, educational, or legal/judicial/correctional systems.

Adaptive Behavior

Accumulating research has shown that children prenatally exposed to alcohol, including both those with FAS and those falling within the wider fetal alcohol spectrum, often have significant adaptive function deficits in areas such as socialization, communication, and daily living skills. These youth show lower performance than might be expected from overall cognitive level, but it should be noted that lower adaptive functioning does not appear specific to more severe prenatal alcohol exposure. Interestingly, comparison of adaptive function between children with FASD and other clinically referred populations has not revealed differences in level of adaptive skills in infancy to early childhood. But they do tend to demonstrate arrested development of social adaptive functioning after the age of 4 to 6 years when compared to peers. Furthermore, difficulties with adaptive behavior do seem highly associated with caregiver stress and with executive function deficits.

Cognition and “Executive Functions”

Among the most commonly recognized difficulties for children diagnosed with FASD are deficits in intellectual status, although a wide range of intellectual abilities, ranging from the above average to well below average, occur.

Early on, alcohol-affected children may show developmental delays. Recent work suggests that over half of such children may show marked developmental delay in the first three years

of life, including those later diagnosed with FAS or partial FAS. Yet as many as one-fourth of these children may show developmental profiles well within normal limits. Among older individuals, cognitive deficits may appear as difficulty understanding abstract concepts and a concrete learning style, poor reasoning skills, or as real-life problems such as poor understanding of time-sensitive tasks and behavior that appears “immature” or younger than expected for their chronological age. A strong correlation has been found between the degree of morphological damage of facial features and cognitive abilities, as assessed by standardized measures, at least among those with the full FAS; this is not true of those without characteristic facial features, and this point is still controversial. For most individuals with FASD, performance on standardized cognitive assessments remains consistent over time, and does not decline with age. Yet although many individuals with FASD may have cognitive skills broadly within the average range, over time the presence of secondary disabilities, such as mental health problems, may mean they do not function at their actual intellectual level, because they are not able to effectively problem solve and process complex information.

Individuals diagnosed with FASD may also show problems with “executive functions.” Specific executive function impairments found in this population may include difficulty with planning ahead, cognitive inflexibility, inability to multitask, and problems in generalizing information from one situation to another. Executive function deficits may manifest themselves in real-life behavior problems such as acting without thinking about consequences or in struggling to plan a sequence of activities or actions.

Attention

Attention deficits have often been cited as a hallmark feature of FASD, perhaps affecting over 60% of children diagnosed with FASD. There may be some specificity in the types of attention deficits, with difficulties in attentional control rather than with global attention deficits. Attention deficits likely impact daily functioning at school and at home. It is thought that attention deficits can be linked to underlying deficits in working memory or to the greater cognitive effort required to respond accurately to attentional demands. A large body of research has noted that these attention deficits manifest themselves independently of cognitive deficits and persist over time.

Language

Prenatal alcohol exposure appears to affect verbal functioning. Individuals with FASD are reported to have difficulty with language learning, verbal fluency, naming, word comprehension, phonological working memory, grammatical and semantic abilities, and pragmatics. Deficits in receptive and expressive language skills impact individuals with FASD across multiple life settings, and contribute to difficulty using language to reason and analyze, and to interpret verbal and nonverbal cues. Importantly, deficits in language skills may often be overlooked or misunderstood earlier in life because many children with FASD can appear very “chatty” and seem to have age-appropriate language, although this may be less true as individuals with FASD grow older, and especially as they try to communicate effectively with peers. An interesting line of research has been tracking problems in higher-level “integrative” language abilities, like the ability to tell cohesive and coherent narratives, which may be a particular problem for those with FASD.

Problems in Learning, Memory, Visual-Spatial Skills, and Fine Motor Performance

Individuals with FASD show difficulties in learning and memory. For example, briefly put, deficits can be seen on measures of verbal fluency, efficient encoding of various kinds of information and, more generally, in working memory. On verbal memory tasks, intrusion errors and perseverative errors are common, and individuals with FASD often experience cognitive

interference. Processing speed, or difficulties in balancing the trade-off between accuracy and speed, are seen. Difficulties are also seen in visual motor integration. Visual—perceptual tasks that require integration of local and global information also appear affected, although it is possible that this may reflect a function of overall intellectual functioning, which is required to efficiently integrate visual—perceptual stimuli. In addition, in the area of motor skills, both fine and gross motor deficits have been found, particularly difficulties in fine motor precision and speed, steadiness, and dynamic movement, and in overall balance.

Academic Achievement and School Performance

Problems in school performance may have many sources, such as deficits in short and long-term memory, cause-and-effect reasoning, difficulty appreciating time or sequencing of events, visual—spatial deficits, or problems with skills such as number processing or phonological processing. As a consequence, individuals affected by prenatal alcohol exposure may show specific academic deficits in areas of reading, writing, and especially, mathematics. School performance may also be affected by problems with adaptive function and maladaptive behavior. Children and adolescents with FASD may appear unmotivated or unorganized, though this may actually arise from underlying difficulties in learning. The situation can become worse, and school performance increasingly affected, when problems go unrecognized, misdiagnosed, or inappropriately treated.