OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Describe the core functions of health-care financing.

Explain how health-care financing may be tailored to address the challenges that vulnerable populations face.

Describe the provisions in the Affordable Care Act and how they affect the financing and organization of health care.

Describe the types of providers that constitute the safety net.

Explain why the organization and financing of the health-care safety net does not adequately meet all the health needs of vulnerable populations.

Articulate the arguments for increasing the numbers of primary care safety net providers to improve the access for vulnerable populations.

INTRODUCTION

John Walsh is a 56-year-old man with essential hypertension and type 2 diabetes. Since being laid off from full-time work, Mr. Walsh and his dependents, a wife and two children, were left without insurance. Neither of his part-time jobs, as a security guard and a deliveryman, offered any health insurance benefits.

Mr. Walsh and his family members have slipped through the cracks of a fragmented system of health-care insurance coverage. The United States has lagged behind almost all developed nations in establishing universal health-care coverage. In 2013, there were approximately 40 million uninsured people in the United States.1 The majority of the uninsured live in households with at least one full-time working adult.2 Absence of insurance creates obstacles to obtaining health care in a timely way. Without a means to pay, patients forgo necessary health services resulting in worsening health.

In 2010, President Obama signed into law the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA establishes an individual mandate for health insurance coverage and has numerous provisions to assist low-income individuals with financing to obtain health insurance. Nonetheless, the ACA has not removed all barriers to health care, nor has it resulted in universal coverage for Americans. The high costs of care and the dearth of providers serving vulnerable populations are persistent and substantial challenges.

A safety net system exists to care for those who face barriers in access to care, such as Mr. Walsh. The safety net is a geographically variable patchwork of providers available to care for individuals with barriers to care, such as a lack of insurance or those residing in a community that is medically underserved because of an inadequate supply of practitioners. Individuals with low family income, minority status, rural residence, limited English proficiency, and poor health status are more vulnerable to not receiving needed health care, and when they do obtain care, they are more likely to receive it from safety net providers. Even in nations with universal financial coverage, safety net programs often exist to address the needs of populations with special access challenges, such as the homeless, recent immigrants, and residents of remote rural regions.

The financing and organization of the health system are the starting points for understanding how health care is delivered to populations. No health system has enough resources to meet the demands of every patient served, not even the United States, which spends close to 18% of its gross domestic product on health. The ways in which health care is financed and organized represent choices about who will receive what services under which conditions.3

This chapter describes the financing of health care in the United States, changes in the financing of health insurance coverage related to the ACA, and the architecture of the safety net available to care for vulnerable populations.

HEALTH SYSTEM FINANCING

Financing of health systems can be characterized by the sources of health system funds and by how the collected funds are structured, whether by pooling to spread risk and ensure financial security of individuals and families or requiring patients who lack insurance coverage to pay directly in order to receive services.

Revenue collection refers to where the money to pay for health care comes from (i.e., the funding sources) and how these resources are obtained (i.e., contribution mechanisms). Nearly all health system revenue in developed nations comes from individuals—as workers, as tax payers, and as patients. In the United States, public funds are raised as taxes on workers, such as the Medicare wage tax, or from federal and state income taxes, and a limited amount from corporate and other types of taxes. Private sector funds come from insurance premium contributions that employees and their employers make. Employers consider their portion of the premium payment to be part of their employee’s total compensation package; so, in fact, it is the employee who actually pays both their own and their employer’s contributions.

Out-of-pocket payments that insured patients incur when they use health services are the second source of private sector funding. An out-of-pocket payment may be made in the form of deductibles (a fixed amount of money that a patient is responsible for paying before the insurer also pays), coinsurance (a percentage of health-care costs that a patient pays up to a maximum out-of-pocket limit), and copayments (a fee paid at the time of every visit). These three types of payments are forms of cost sharing, and are used by insurers to reduce utilization and shift costs to individuals using services. For low-income families, cost sharing can be so burdensome that they forgo necessary care with inimical effects on their health.4

A second type of out-of-pocket payment results from direct payments made to providers by patients with no insurance. Direct payments offer no financial protection and can be very burdensome for vulnerable populations.

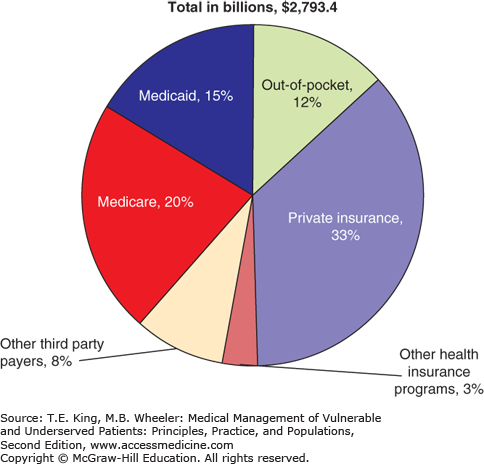

The distribution of the various sources of health system revenue in the United States is shown in Figure 3-1. Note that health system revenue in the United States is collected in approximately equal proportions using public and private sector mechanisms. This pluralistic mix of revenue contributions to the health system is one of the many obstacles in the United States to achieving a system of universal coverage.

Figure 3-1.

National health-care source of funds, 2012. (Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2012 National Health Expenditure Data [Online]. Available at http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/tables.pdf.)

When revenue is collected on a prepaid basis (rather than at the time care is received), and aggregated across many individuals, an insurance risk pool is formed. Protecting individuals from the financial impact of health-care costs is best achieved with prepayment and risk pooling. At the individual level, health-care events are largely unpredictable and, when they occur, can be costly. By pooling resources, health insurers, whether they are private plans or government-sponsored insurers, spread the risk of financial loss due to health care across the all contributors. This provides a level of financial security to a given individual that cannot be achieved without risk pooling. To sustain themselves, risk pools require large numbers of healthy individuals who in effect cover the costs of those who are sick and require more resources. Individuals are willing to participate in risk pools because of the uncertainty of illness at the individual level.

Low-income individuals may not have the financial means to participate in a health insurance risk pool. Individuals with no health insurance coverage must pay for services entirely out of pocket, rendering low-income individuals in general and those with high health-care needs in particular susceptible to financial hardship, because they are not part of a financing pool that shares financial risk.

Even when insured, many individuals may have plans with high amounts of cost sharing that cause financial hardship. Having insurance with high levels of cost sharing is a form of underinsurance, which can pose as large a financial barrier to care as having no insurance at all. Underinsurance refers to insurance that does not provide adequate financial coverage to address an individual or family’s health needs. High-deductible health plans are an example of insurance that provides coverage for expensive care, but requires patients to cover the first several thousand dollars of health-care costs on an annual basis. One-third of low-income insured individuals are actually underinsured.5 When enrolled in high-deductible health plans, low-income families and individuals with chronic conditions are at increased risk for delaying or forgoing needed health care, including physician visits and medications.6

The ill effects of being uninsured extend beyond delaying care: poor health that results from lack of insurance reduces income by an estimated 15–30%, and people with lower incomes are less likely to have health insurance.7,8 Costs associated with illness and injury in the United States are the most common reason to declare personal bankruptcy,9 and many of these bankruptcies have been among insured patients with insufficiently comprehensive benefits.

Most industrialized and many developing nations provide health-care coverage to their populations as a form of social security. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service is funded by general taxes, whereas in Germany, sickness funds are sponsored by worker payroll taxes and government contributions. The ACA, signed into law in 2010, is intended to move the United States closer to universal coverage through a combination of private insurance regulatory changes and increased availability and affordability of insurance for low-income persons.

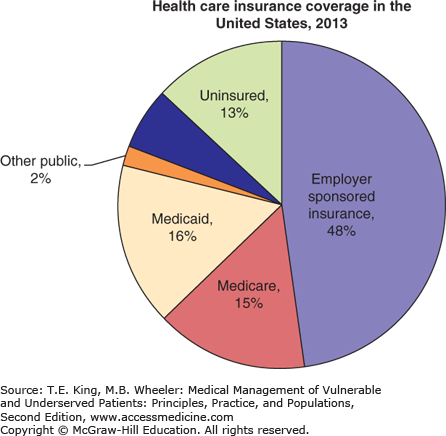

The major provisions to expand health insurance coverage as a part of the ACA were implemented in 2014. In 2013, 13% of Americans reported that they were uninsured; 48% reported that they obtained coverage through a voluntary system of employer-sponsored health-care insurance benefits, 6% purchased individual private insurance policies, and most of the remainder were covered by two major public insurance programs, Medicare and Medicaid (Figure 3-2). For low-income persons younger than 65 years, just 10% received employer-sponsored health insurance, 8% purchased it as individuals, and 27% were uninsured (the balance got their coverage from publicly sponsored programs).10,11

Figure 3-2.

Health-care insurance coverage in the United States, 2013. Categories are mutually exclusive; persons cannot be in more than one insurance category. The “Other Public” insurance category includes nonelderly Medicaid enrollees as well as individuals covered through the military or Veterans Administration. (Source: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014 estimates. Available at http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/.)

Health-care policy in the United States focused on improving insurance coverage rates and has largely developed via an “incrementalist” approach in which government confers health benefits to defined categories of the population.12 Medicare, the Indian Health Service, and the Veterans Administration’s (VA) medical system are programs sponsored by the federal government, and are entitlements where, respectively, all US citizens aged 65 years and older, Native American/Alaskan natives, and veterans are guaranteed insurance coverage. These three programs contrast with Medicaid, which is a means-tested publicly sponsored insurance benefit that, prior to implementation of the ACA, limited eligibility to a subset of poor individuals. Because of their size and importance to vulnerable populations, we discuss Medicare, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in more detail in the following.

Medicare is a federal program insuring the elderly, disabled, and those with end-stage renal disease.13 The program was created in 1965. All elderly US citizens aged 65 years and older who have paid into Social Security for at least 10 years are guaranteed coverage under Part A (“hospital insurance”). Inpatient services, short-term stays at skilled nursing facilities, hospice care, and some home health care are paid through this program, funded through a payroll tax on currently employed workers.

Medicare Part B (“medical insurance”) provides limited coverage of outpatient services and requires beneficiaries to pay a monthly premium. Many elderly individuals without sufficient incomes to pay for Part B premiums are eligible to have state Medicaid programs pay their Part B premiums, as well as some of their other out-of-pocket costs. Individuals who receive both Medicare and Medicaid coverage are termed “dual-eligibles.”

The 1997 Balanced Budget Act instituted Medicare Part C, called Medicare + Choice, to allow beneficiaries to opt into managed care plans in lieu of enrolling in Medicare Part A and Part B. In 2014, 30% of Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan.14

The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 added Medicare Part D, a voluntary prescription drug benefit.15

Medicaid was also created in 1965, but unlike Medicare, which is funded from federal and beneficiary funds, Medicaid is funded by federal and state revenues with no beneficiary premiums. The amount of federal matching funds a state receives reflects the economic status of a state as well as the size and eligibility profile of a state’s vulnerable populations. Federal guidelines govern the administration of the programs but allow for substantial flexibility in coverage and implementation, rendering each state’s Medicaid program unique.

Medicaid beneficiaries must meet the residency standards of the state and federal immigration standards, and prior to the ACA, be a member of a population eligible for coverage (e.g., pregnant women, children, and disabled persons), and satisfy income and asset requirements. As a result of these “categorical” eligibility criteria, the main classes of Medicaid beneficiaries are low-income children and their parents, pregnant women, low-income disabled individuals (who must first meet state requirements for Supplemental Security Income, SSI), and low-income elderly with Medicare coverage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree