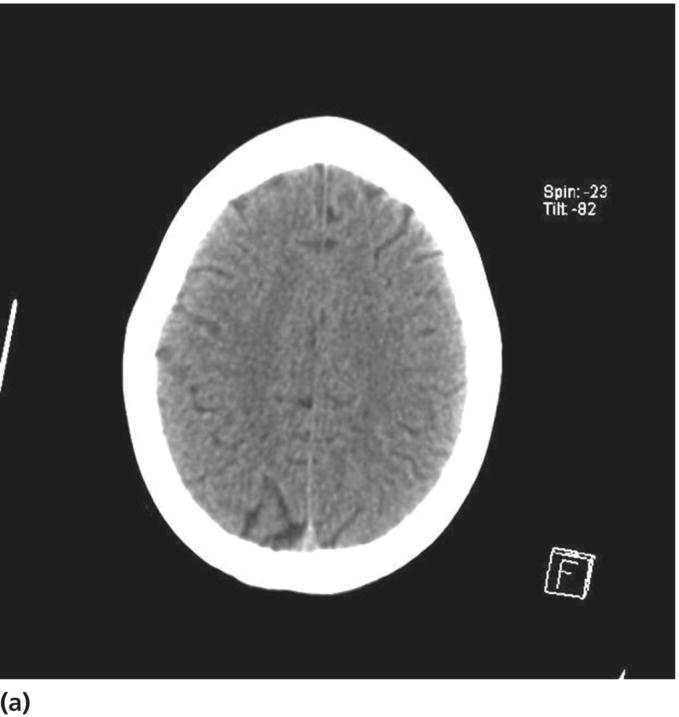

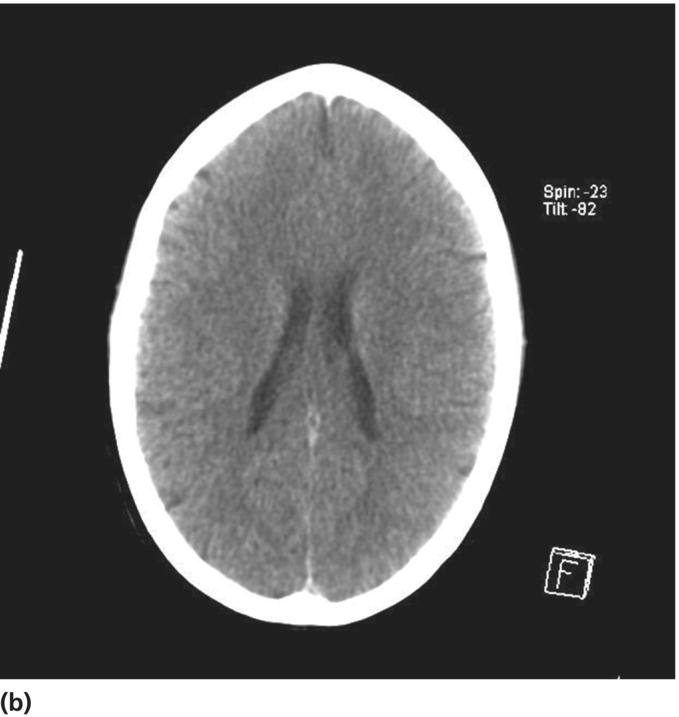

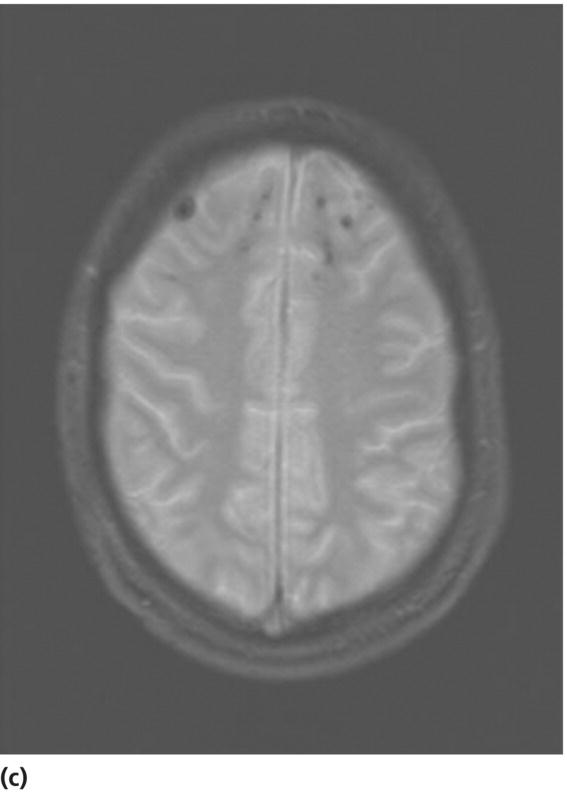

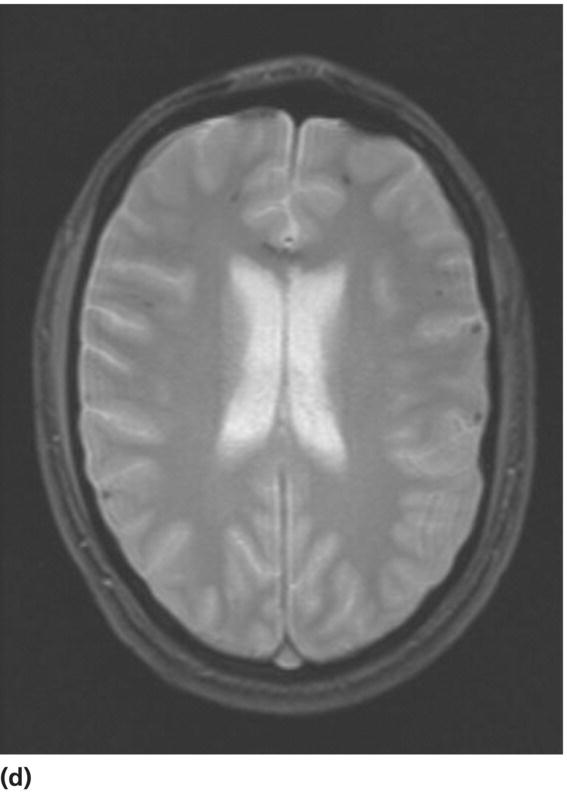

Chapter 12 Joukje van der Naalt1 and Joke M. Spikman2 1 Department of Neurology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningenthe Netherlands 2 Department of Neuropsychology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningenthe Netherlands Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an important cause of disability and death in young adults [1, 2]. The majority (80–90%) of patients admitted to the emergency department are classified as mild TBI [3]. The definition of mild TBI according to the Task Force on mild TBI of the WHO Collaborating Center for Neurotrauma [4] comprises the following criteria: Most of these patients recover within weeks to months without specific therapy. However, a subgroup of 15–25% patients continues to experience disabling postconcussive symptoms (PCS) that interfere with their return to work or resumption of social activities [5, 6]. These symptoms cause a social economical burden, since TBI often affects young patients in their twenties and thirties with full occupational status. The financial costs associated with unemployment after TBI are substantial, given that TBI disproportionally affects young people of working age [7]. Lost work productivity after mild TBI may be the largest component of economic costs of brain trauma in the USA [8]. In the USA, costs associated with care and management of TBI are estimated to be $22 billion annually [9]. In health care, indirect costs are much higher than direct costs. Admission and radiological policies are determining factors for the level of direct costs, whereas loss of productivity is the main expense for indirect costs. As minimal data are available regarding the lost work productivity in the majority of patients who are not hospitalized, economic costs of brain injury are substantially underestimated. Given the economic consequences, it is of paramount importance to identify those patients who are prone to develop chronic postconcussive problems in order to institute early rehabilitation focusing on resumption of previous activities [10, 11]. Several protocols are applied to optimize patient care and management. According to international guidelines, a brain computed tomography (CT) scan is performed at the Emergency Department (ER) on all patients with a GCS of 15 or less and in the presence of certain risk factors (see Chapter 4) [12, 13]. Only patients with documented brain injury are admitted to the neurological or surgical ward. In general, follow-up of patients after sustaining a mild TBI is only done in patients with abnormalities on admission CT. When a CT scan reveals no abnormalities in the acute phase after injury, the patient is regarded as having sustained no relevant TBI and is not seen for follow-up. However, routine CT imaging appears rather insensitive for detecting structural brain changes which may account for persistent symptoms as 20% of the patients with a normal CT scan on admission will develop cognitive complaints. On the other hand, 22% of patients with CT abnormalities showed good outcome [14]. Especially in mild TBI, CT abnormalities are rather nonspecific, and therefore, clinical variables and age are found to be stronger predictions for outcome than CT abnormalities [15]. Only when a patient experiences residual deficits does a referral to a neurologist or rehabilitation specialist occur, and eventually, a neuropsychological examination and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are performed. In general, referral occurs within several months after injury due to late recognition of residual impairments and because no practice-based guidelines for a multidisciplinary approach are available [6]. Routine follow-up or interventions are not useful for most patients with mild TBI as the vast majority of improvement occurs between the time of injury and 3 months following the injury. For those patients admitted to the hospital, one regular follow-up either at the hospital or with the general practitioner is advised in most recent guidelines [14]. Mostly, patients are admitted to the outpatient clinic within 4–6 weeks after injury. In those patients with complaints that interfere with resumption of work, additional diagnostic procedures (MRI, neuropsychological assessment) are performed to evaluate whether these impairments are related to the injury or to concomitant anxiety or depression. With the acquired information of these diagnostic procedures, individual targeted rehabilitation therapy can be instituted (Figure 12.1). Figure 12.1 Flow diagram with follow-up scheme of mild TBI. LOC, loss of consciousness; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NPO, neuropsychological assessment; PTA, posttraumatic amnesia. Some studies reveal that early targeted educational intervention that includes reassuring information can reduce long-term complaints [16]. A single-session educational intervention within 3 weeks after injury was found to be as effective as a more elaborate assessment. However, many patients had returned to work before the intervention and as such the lack of treatment effect may be due to lack of persistent symptoms in the participants [17]. Early follow-up within 7 days after injury was only found to be effective in hospitalized patients with PTA durations of more than 1 h, resulting in significantly fewer difficulties with everyday activities and lower ratings of PCS at 6 months after injury [18]. In a systematic review [19], it was recommended to apply cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in those patients with symptoms not responding to information and education alone as this treatment may not be as beneficial as previously thought. Future research on effective treatments can probably focus more on developing early brief treatments targeted to a specific problem group than studying potentially more extensive and expensive rehabilitation models for all mild TBI survivors. In the acute phase after injury, CT is the standard imaging technique because of more accurate detection of intracranial blood to determine eligibility for eventual neurosurgical intervention (see Chapter 4) [20]. For mild TBI, the incidence of abnormalities is about 15% increasing to 50% when a CT scan is done only in those with neurological symptoms [21]. Conventional CT has limited ability to detect structural and functional abnormalities as suggested by the fact that 20% of patients with a normal CT scan on admission show unfavorable outcome [14]. MRI is the preferred imaging technique in the subacute phase and during follow-up of mild TBI as MRI is more sensitive in detecting diffuse axonal injury and nonhemorragic contusions (see Chapter 2) [22]. For years, T1- and T2-weighted spin echo and FLAIR-weighted sequences were the most commonly used MRI modalities in TBI. Nowadays, T2*-weighted gradient echo is used instead of these conventional sequences because of better detection of diffuse axonal injury, with visualization of hemosiderin deposits as a result of hemorrhage [23, 24]. The number of T2*-weighted abnormalities are found to correlate with outcome and with neuropsychological deficits [23, 25, 26]. Susceptibility-weighted imaging is the most recently developed structural MRI technique with high sensitivity for hemosiderin. The first studies are promising as they show high sensitivity but a rather inconsistent relation with outcome [27, 28] (Figure 12.2). Figure 12.2 Patient with mild TBI, GCS 14 on admission, after a bicycle accident. CT on admission reveals no abnormalities (a and b). MRI performed 3 months after injury due to persisting cognitive complaints reveals microhemorrhages corresponding with diffuse axonal injury in the frontal regions bilaterally (c) and in the corpus callosum and in the cortex (d). The outcome after mild TBI in general is favorable with 75–90% of patients achieving good outcome 1 year after injury [29] measured with the Glasgow Outcome Scale. Although the majority of symptoms are present in the first 3 months after injury, still, 25–50% of patients will have persistent complaints interfering with resumption of work and social activities. The most frequent complaints after mild TBI are forgetfulness, concentration problems, and increased fatigue [30–32]. In one of the first studies on outcome of mild TBI, moderate disability was found in one out of four patients [33]. For determination of outcome and return to work, timing of follow-up is important. One month after injury, physical limitations play a role in resuming work [34] with considerable improvement noted over the first 6 months postinjury, whereas some of the reported limitations in communication and emotional domains remain constant over time [35]. Deficits in cognitive functioning are not consistently demonstrated with standard neuropsychological tests despite the often reported attention and memory complaints. Some studies report cognitive deficits in the early stage postinjury. For instance, Kwok et al. [36] found mild TBI patients to be impaired on tests for speed of information processing, attention, and memory at 1 month postinjury. However, at 3 months postinjury, patients were reassessed, and most test performances had returned to a normal level or were only present in those patients with CT abnormalities on admission [37]. A meta-analysis by Binder et al. [38] showed evidence for subtle neuropsychological deficits in mild TBI patients assessed more than 3 months postinjury, but more recent meta-analyses fail to detect significant long-term neuropsychological impairments [39–41]. Furthermore, poor test performances of mild TBI might be the consequence of poor effort [42]. More than 25% of a sample of mild TBI patients failed a symptom validity test, indicating poor effort. Strikingly, this was not related to litigation, but to lower educational levels as well as reported high levels of distress. It is also demonstrated that the mere expectation that an individual will experience cognitive symptoms influences the extent to which they are actually experienced. Studies investigating mild TBI patients under a condition of diagnosis threat (in which they were told that they may be experiencing cognitive problems due to the injury) versus a neutral condition found lower performances on cognitive tests as well as higher complaint ratings for the first group, even on a long term [43–45]. The majority of patients with mild TBI will have returned to work by 3 months after injury [30, 46]. In most studies, only the first day of working is noted without defining the level of work that the patient could achieve or the percentage of the total working hours. One recent study showed that the majority of patients with mild TBI (56%) started working until 1 and 3 months after injury. Ultimately, 91% of the patients were working in a full-time job at 6 months postinjury [47]. However, this does not imply that patients resuming work are without complaints. Work-related problems were reported by up to half of employed patients. Even patients who have resumed work completely report temporary increase of postconcussive complaints in the first months after regaining full activities, suggesting that patients who are resuming activities show suboptimal performance [32]. Given the long-term consequences, lost work productivity should not only be measured by work absence but also by estimation of reduced performance on the job. Outcome studies beyond 10 years after injury contain patients with varying severity of injury hampering the precise estimation of long-term outcome. Furthermore, the response rate is often low in mild TBI probably due to relative favorable outcome of this patient category. However, the few studies on long-term follow-up on mild TBI ultimately show good recovery varying from 50 to 88 % of patients [48, 49]. Approximately 95% of patients found their life as a whole at follow-up good or at least acceptable. An important factor influencing survival seemed to be whether relations with family and friends could be maintained at preinjury levels [50]. Up to 30% reported distressed family relations 1 year after injury. Emotional and behavioral impairments are also noted 1 year after injury [51]. Even though patients are found to live and work independently several years postinjury, they still may have difficulties in social interactions due to personality disturbances [52]. Over the years, changes in adjustment show improvement of emotional stability but increased difficulties with anger management and self-monitoring [53]. In those with milder injuries, adverse psychosocial factors are associated with deterioration [54]. At follow-up 5–7 years after injury, as many had deteriorated (12%) as had improved (13%). Those who deteriorated were more depressed and anxious and had more alcohol-related problems [55]. When comparing a mild to a moderate–severe TBI group in a cohort study beyond 10 years after injury, no substantial difference was found between injury severity groups in case of living arrangements, marital status, education, or quality of life. In addition, cognitive impairment and emotional problems were more commonly reported than physical impairment in the long term with 10–25% of patients reporting some degree of feelings of depression or anxiety [56, 57]. Approximately 1 in 10 patients was found to have lost their jobs because of persistent complaints [58]. Long-term outcome surveys in mild TBI indicate that self-reported outcomes and adaptation to impairment-related limitations improve as the time since injury increase, especially in the mild TBI group [59] (Table 12.1). Table 12.1 Long-term outcome studies of mild TBI. Studies with 100 or more patients are selected.

Follow-up and community integration of mild traumatic brain injury

Care as usual

Follow-up

Imaging

Outcome of mild TBI

Postconcussive symptoms

Cognitive impairment

Return to work

Long-term outcome and community integration

Author

Severity

Follow-up

Impairments

Outcome (for mild TBI)

Return to previous work

Engberg [50]

Register-based questionnaire survey

2–5 years

42%, behavioral disturbances

65%, good recovery*

42%

Response 76%

n = 240 mild TBI

25%, less social contacts

Kashluba [37]

Prospective outcome study

1 year

29%, cognitive problems

Not specified

61%

n = 102 mild TBI with abnormal CT

Huang [52]

Level 1 trauma center

1–10 years

Not assessed

Good recovery†

50%, 1 year

Response 33%

n = 327

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access