Forensic Psychiatry and Ethics in Psychiatry

36.1 Forensic Psychiatry

36.1 Forensic Psychiatry

The word forensic means belonging to the courts of law, and at various times, psychiatry and the law converge. Forensic psychiatry covers a broad range of topics that involve psychiatrists’ professional, ethical, and legal duties to provide competent care to patients; the patients’ rights of self-determination to receive or refuse treatment; court decisions, legislative directives, governmental regulatory agencies, and licensure boards; and the evaluation of those charged with crimes to determine their culpability and ability to stand trial. Finally, the ethical codes and practice guidelines of professional organizations and their adherence also fall within the realm of forensic psychiatry.

MEDICAL MALPRACTICE

Medical malpractice is a tort, or civil wrong. It is a wrong resulting from a physician’s negligence. Simply put, negligence means doing something that a physician with a duty to care for the patient should not have done or failing to do something that should have been done as defined by current medical practice. Usually, the standard of care in malpractice cases is established by expert witnesses. The standard of care is also determined by reference to journal articles; professional textbooks, such as the Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry; professional practice guidelines; and ethical practices promulgated by professional organizations.

To prove malpractice, the plaintiff (e.g., patient, family, or estate) must establish by a preponderance of evidence that (1) a doctor–patient relationship existed that created a duty of care, (2) a deviation from the standard of care occurred, (3) the patient was damaged, and (4) the deviation directly caused the damage.

These elements of a malpractice claim are sometimes referred to as the 4 Ds (duty, deviation, damage, direct causation).

Each of the four elements of a malpractice claim must be present or there can be no finding of liability. For example, a psychiatrist whose negligence is the direct cause of harm to an individual (physical, psychological, or both) is not liable for malpractice if no doctor–patient relationship existed to create a duty of care. Psychiatrists are not likely to be sued successfully if they give advice on a radio program that is harmful to a caller, particularly if a caveat was given to the caller that no doctor–patient relationship was being created. No malpractice claim will be sustained against a psychiatrist if a patient’s worsening condition is unrelated to negligent care. Not every bad outcome is the result of negligence. Psychiatrists cannot guarantee correct diagnoses and treatments. When the psychiatrist provides due care, mistakes may be made without necessarily incurring liability. Most psychiatric cases are complicated. Psychiatrists make judgment calls when selecting a particular treatment course among the many options that may exist. In hindsight, the decision may prove wrong but not be a deviation in the standard of care.

In addition to negligence suits, psychiatrists can be sued for the intentional torts of assault, battery, false imprisonment, defamation, fraud or misrepresentation, invasion of privacy, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. In an intentional tort, wrongdoers are motivated by the intent to harm another person or realize, or should have realized, that such harm is likely to result from their actions. For example, telling a patient that sex with the therapist is therapeutic perpetrates a fraud. Most malpractice policies do not provide coverage for intentional torts.

Negligent Prescription Practices

Negligent prescription practices usually include exceeding recommended dosages and then failing to adjust the medication level to therapeutic levels, unreasonable mixing of drugs, prescribing medication that is not indicated, prescribing too many drugs at one time, and failing to disclose medication effects. Elderly patients frequently take a variety of drugs prescribed by different physicians. Multiple psychotropic medications must be prescribed with special care because of possible harmful interactions and adverse effects.

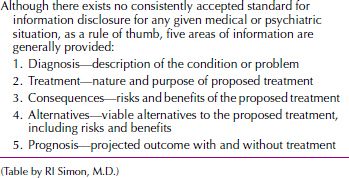

Psychiatrists who prescribe medications must explain the diagnosis, risks, and benefits of the drug within reason and as circumstances permit (Table 36.1-1). Obtaining competent informed consent can be problematic if a psychiatric patient has diminished cognitive capacity because of mental illness or chronic brain impairment; a substitute health care decision maker may need to provide consent.

Table 36.1-1

Table 36.1-1

Informed Consent: Reasonable Information to Be Disclosed

Informed consent should be obtained each time a medication is changed and a new drug is introduced. If patients are injured because they were not properly informed of the risks and consequences of taking a medication, sufficient grounds may exist for a malpractice action.

The question is often asked: How frequently should patients be seen for medication follow-up? The answer is that patients should be seen according to their clinical needs. No stock answer about the frequency of visits can be given. The longer the time interval between visits, however, the greater the likelihood of adverse drug reactions and clinical developments. Patients taking medications should probably not go beyond 6 months for follow-up visits. Managed care policies that do not reimburse for frequent follow-up appointments can result in a psychiatrist prescribing large amounts of medications. The psychiatrist is duty bound to provide appropriate treatment to the patient, quite apart from managed care or other payment policies.

Other areas of negligence involving medication that have resulted in malpractice actions include failure to treat adverse effects that have, or should have, been recognized; failure to monitor a patient’s compliance with prescription limits; failure to prescribe medication or appropriate levels of medication according to the treatment needs of the patient; prescribing addictive drugs to vulnerable patients; failure to refer a patient for consultation or treatment by a specialist; and negligent withdrawal of medication treatment.

Split Treatment

In split treatment, the psychiatrist provides medication, and a nonmedical therapist conducts the psychotherapy. The following vignette illustrates a possible complication.

A psychiatrist provided medications for a depressed 43-year-old woman. A master’s level counselor saw the patient for outpatient psychotherapy. The psychiatrist saw the patient for 20 minutes during the initial evaluation and prescribed a tricyclic drug, and the patient was prescribed sufficient drugs for follow-up in 3 months. The psychiatrist’s initial diagnosis was recurrent major depression. The patient denied suicidal ideation. Appetite and sleep were markedly diminished. The patient had a long history of recurrent depression with suicide attempts. No further discussions were held between the psychiatrist and the counselor, who saw the patient once a week for 30 minutes in psychotherapy. Within 3 weeks, after a failed romantic relationship, the patient stopped taking her antidepressant medication, started to drink heavily, and committed suicide with an overdose of alcohol and antidepressant drugs. The counselor and psychiatrist were sued for negligent diagnosis and treatment.

Psychiatrists must do an adequate evaluation, obtain prior medical records, and understand that no such thing as a partial patient exists. Split treatments are potential malpractice traps because patients can “fall between the cracks” of fragmented care. The psychiatrist retains full responsibility for the patient’s care in a split treatment situation. This does not preempt the responsibility of the other mental health professionals involved in the patient’s treatment. Section V, annotation 3 of the Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry, states: “When the psychiatrist assumes a collaborative or supervisory role with another mental health worker, he/she must expend sufficient time to assure that proper care is given.”

In managed care or other settings, a marginalized role of merely prescribing medication apart from a working doctor–patient relationship does not meet generally accepted standards of good clinical care. The psychiatrist must be more than just a medication technician. Fragmented care in which the psychiatrist only dispenses medication while remaining uninformed about the patient’s overall clinical status constitutes substandard treatment that may lead to a malpractice action. At a minimum, such a practice diminishes the efficacy of the drug treatment itself or may even lead to the patient’s failure to take the prescribed medication.

Split-treatment situations require that the psychiatrist remain fully informed of the patient’s clinical status as well as the nature and quality of treatment the patient is receiving from the nonmedical therapist. In a collaborative relationship, the responsibility for the patient’s care is shared according to the qualifications and limitations of each discipline. The responsibilities of each discipline do not diminish those of the other disciplines. Patients should be informed of the separate responsibilities of each discipline. The psychiatrist and the nonmedical therapist must periodically evaluate the patient’s clinical condition and requirements to determine whether the collaboration should continue. On termination of the collaborative relationship, both parties treating the patient should inform the patient either separately or jointly. In split treatments, if the nonmedical therapist is sued, the collaborating psychiatrist will likely be sued also and vice versa.

Psychiatrists who prescribe medications in a split-treatment arrangement should be able to hospitalize a patient if it becomes necessary. If the psychiatrist does not have admitting privileges, prearrangements should be made with other psychiatrists who can hospitalize patients if emergencies arise. Split treatment is increasingly used by managed care companies and is a potential malpractice minefield.

PRIVILEGE AND CONFIDENTIALITY

Privilege

Privilege is the right to maintain secrecy or confidentiality in the face of a subpoena. Privileged communications are statements made by certain persons within a relationship—such as husband–wife, priest–penitent, or doctor–patient—that the law protects from forced disclosure on the witness stand. The right of privilege belongs to the patient, not to the physician, so the patient can waive the right.

Psychiatrists, who are licensed to practice medicine, may claim medical privilege, but privilege has some qualifications. For example, privilege does not exist at all in military courts, regardless of whether the physician is military or civilian and whether the privilege is recognized in the state in which the court martial takes place.

In 1996, the United States Supreme Court recognized a psychotherapist–patient privilege in Jaffee v. Redmon. Emphasizing the important public and private interests served by the psychotherapist–patient privilege, the Court wrote: Because we agree with the judgment of the state legislatures and the Advisory Committee that a psychotherapist-patient privilege will serve a “public good transcending the normal predominant principle utilizing all rational means for ascertaining truth”… we hold that confidential communications between a licensed psychotherapist and her patients in the course of diagnosis or treatment are protected from compelled disclosure under Rule 501 of the Federal Rules of Evidence.

Confidentiality

A long-held premise of medical ethics binds physicians to hold secret all information given by patients. This professional obligation is called confidentiality. Confidentiality applies to certain populations and not to others; a group that is within the circle of confidentiality shares information without receiving specific permission from a patient. Such groups include, in addition to the physician, other staff members treating the patient, clinical supervisors, and consultants.

A subpoena can force a psychiatrist to breach confidentiality, and courts must be able to compel witnesses to testify for the law to function adequately. A subpoena (“under penalty”) is an order to appear as a witness in court or at a deposition. Physicians usually are served with a subpoena duces tecum, which requires that they also produce their relevant records and documents. Although the power to issue subpoenas belongs to a judge, they are routinely issued at the request of an attorney representing a party to an action.

In bona fide emergencies, information may be released in as limited a way as feasible to carry out necessary interventions. Sound clinical practice holds that a psychiatrist should make the effort, time allowing, to obtain the patient’s permission anyway and should debrief the patient after the emergency.

As a rule, clinical information may be shared with the patient’s permission—preferably written permission, although oral permission suffices with proper documentation. Each release is good for only one piece of information, and permission should be reobtained for each subsequent release, even to the same party. Permission overcomes only the legal barrier, not the clinical one; the release is permission, not obligation. If a clinician believes that the information may be destructive, the matter should be discussed, and the release may be refused, with some exceptions.

Third-Party Payers and Supervision. Increased insurance coverage for health care is precipitating a concern about confidentiality and the conceptual model of psychiatric practice. Today, insurance covers about 70 percent of all health care bills; to provide coverage, an insurance carrier must be able to obtain information with which it can assess the administration and costs of various programs.

Quality control of care necessitates that confidentiality not be absolute; it also requires a review of individual patients and therapists. The therapist in training must breach a patient’s confidence by discussing the case with a supervisor. Institutionalized patients who have been ordered by a court to get treatment must have their individualized treatment programs submitted to a mental health board.

Discussions About Patients. In general, psychiatrists have multiple loyalties: to patients, to society, and to the profession. Through their writings, teaching, and seminars, they can share their acquired knowledge and experience and provide information that may be valuable to other professionals and to the public. It is not easy to write or talk about a psychiatric patient, however, without breaching the confidentiality of the relationship. Unlike physical ailments, which can be discussed without anyone’s recognizing the patient, a psychiatric history usually entails a discussion of distinguishing characteristics. Psychiatrists have an obligation not to disclose identifiable patient information (and, perhaps, any descriptive patient information) without appropriate informed consent. Failure to obtain informed consent could result in a claim based on breach of privacy, defamation, or both.

Internet and Social Media. It is imperative that psychiatrists and other mental health professionals be aware of the legal implications of discussing patients over the Internet. Internet communications about patients are not confidential, are subject to hacking, and are open to legal subpoenas. Some psychiatrists have blogged about patients thinking they were sufficiently disguised only to find that they were recognized by others, including the involved patient. Some professional organizations have electronic mailing lists in which they ask advice about patients from their colleagues or make referrals and in so doing provide detailed information about the patient that can easily be traced. Similarly, using social media to communicate about patients is equally risky.

Child Abuse. In many states, all physicians are legally required to take a course on child abuse for medical licensure. All states now legally require that psychiatrists, among others, who have reason to believe that a child has been the victim of physical or sexual abuse make an immediate report to an appropriate agency. In this situation, confidentiality is decisively limited by legal statute on the grounds that potential or actual harm to vulnerable children outweighs the value of confidentiality in a psychiatric setting. Although many complex psychodynamic nuances accompany the required reporting of suspected child abuse, such reports generally are considered ethically justified.

HIGH-RISK CLINICAL SITUATIONS

Tardive Dyskinesia

It is estimated that at least 10 to 20 percent of patients and perhaps as high as 50 percent of patients treated with neuroleptic drugs for more than 1 year exhibit some tardive dyskinesia. These figures are even higher for elderly patients. Despite the possibility for many tardive dyskinesia–related suits, relatively few psychiatrists have been sued. In addition, patients who develop tardive dyskinesia may not have the physical energy and psychological motivation to pursue litigation. Allegations of negligence involving tardive dyskinesia are based on a failure to evaluate a patient properly, a failure to obtain informed consent, a negligent diagnosis of a patient’s condition, and a failure to monitor.

Suicidal Patients

Psychiatrists may be sued when their patients commit suicide, particularly when psychiatric inpatients kill themselves. Psychiatrists are assumed to have more control over inpatients, making the suicide preventable.

The evaluation of suicide risk is one of the most complex, dauntingly difficult clinical tasks in psychiatry. Suicide is a rare event. In our current state of knowledge, clinicians cannot accurately predict when or if a patient will commit suicide. No professional standards exist for predicting who will or will not commit suicide. Professional standards do exist for assessing suicide risk, but at best, only the degree of suicide risk can be judged clinically after a comprehensive psychiatric assessment.

A review of the case law on suicide reveals that certain affirmative precautions should be taken with a suspected or confirmed suicidal patient. For example, failing to perform a reasonable assessment of a suicidal patient’s risk for suicide or implement an appropriate precautionary plan will likely render a practitioner liable. The law tends to assume that suicide is preventable if it is foreseeable. Courts closely scrutinize suicide cases to determine if a patient’s suicide was foreseeable. Foreseeability is a deliberately vague legal term that has no comparable clinical counterpart, a common-sense rather than a scientific construct. It does not (and should not) imply that clinicians can predict suicide. Foreseeability should not be confused with preventability, however. In hindsight, many suicides seem preventable that were clearly not foreseeable.

Violent Patients

Psychiatrists who treat violent or potentially violent patients may be sued for failure to control aggressive outpatients and for the discharge of violent inpatients. Psychiatrists can be sued for failing to protect society from the violent acts of their patients if it was reasonable for the psychiatrist to have known about the patient’s violent tendencies and if the psychiatrist could have done something that could have safeguarded the public. In the landmark case Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, the California Supreme Court ruled that mental health professionals have a duty to protect identifiable, endangered third parties from imminent threats of serious harm made by their outpatients. Since then, courts and state legislatures have increasingly held psychiatrists to a fictional standard of having to predict the future behavior (dangerousness) of their potentially violent patients. Research has consistently demonstrated that psychiatrists cannot predict future violence with any dependable accuracy.

The duty to protect patients and endangered third parties should be considered primarily a professional and moral obligation and, only secondarily, a legal duty. Most psychiatrists acted to protect both their patients and others threatened by violence long before Tarasoff.

If a patient threatens harm to another person, most states require that the psychiatrist perform some intervention that might prevent the harm from occurring. In states with duty-to-warn statutes, the options available to psychiatrists and psychotherapists are defined by law. In states offering no such guidance, health care providers are required to use their clinical judgment and act to protect endangered third persons. Typically, a variety of options to warn and protect are clinically and legally available, including voluntary hospitalization, involuntary hospitalization (if civil commitment requirements are met), warning the intended victim of the threat, notifying the police, adjusting medication, and seeing the patient more frequently. Warning others of danger, by itself, is usually insufficient. Psychiatrists should consider the Tarasoff duty to be a national standard of care, even if they practice in states that do not have a duty to warn and protect.

Tarasoff I. This issue was raised in 1976 in the case of Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California (now known as Tarasoff I). In this case, Prosenjiit Poddar, a student and a voluntary outpatient at the mental health clinic of the University of California, told his therapist that he intended to kill a student readily identified as Tatiana Tarasoff. Realizing the seriousness of the intention, the therapist, with the concurrence of a colleague, concluded that Poddar should be committed for observation under a 72-hour emergency psychiatric detention provision of the California commitment law. The therapist notified the campus police, both orally and in writing, that Poddar was dangerous and should be committed.

Concerned about the breach of confidentiality, the therapist’s supervisor vetoed the recommendation and ordered all records relating to Poddar’s treatment destroyed. At the same time, the campus police temporarily detained Poddar but released him on his assurance that he would “stay away from that girl.” Poddar stopped going to the clinic when he learned from the police about his therapist’s recommendation to commit him. Two months later, he carried out his previously announced threat to kill Tatiana. The young woman’s parents thereupon sued the university for negligence.

As a consequence, the California Supreme Court, which deliberated the case for the unprecedented time of about 14 months, ruled that a physician or a psychotherapist who has reason to believe that a patient may injure or kill someone warn the potential victim.

The discharge of the duty imposed on the therapist to warn intended victims against danger may take one or more forms, depending on the case. Therefore, stated the court, it may call for the therapist to notify the intended victim or others likely to notify the victim of the danger, to notify the police, or to take whatever other steps are reasonably necessary under the circumstances.

The Tarasoff I ruling does not require therapists to report a patient’s fantasies; instead, it requires them to report an intended homicide, and it is the therapist’s duty to exercise good judgment.

Tarasoff II. In 1982, the California Supreme Court issued a second ruling in the case of Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California (now known as Tarasoff II), which broadened its earlier ruling extending the duty to warn to include the duty to protect.

The Tarasoff II ruling has stimulated intense debates in the medicolegal field. Lawyers, judges, and expert witnesses argue the definition of protection, the nature of the relationship between the therapist and the patient, and the balance between public safety and individual privacy.

Clinicians argue that the duty to protect hinders treatment because a patient may not trust a doctor if confidentiality is not maintained. Furthermore, because it is not easy to determine whether a patient is sufficiently dangerous to justify long-term incarceration, unnecessary involuntary hospitalization may occur because of a therapist’s defensive practices.

As a result of such debates in the medicolegal field, since 1976, the state courts have not made a uniform interpretation of the Tarasoff II ruling (the duty to protect). Generally, clinicians should note whether a specific identifiable victim seems to be in imminent and probable danger from the threat of an action contemplated by a mentally ill patient; the harm, in addition to being imminent, should be potentially serious or severe. Usually, the patient must be a danger to another person and not to property; the therapist should take clinically reasonable action.

HOSPITALIZATION

All states provide for some form of involuntary hospitalization. Such action usually is taken when psychiatric patients present a danger to themselves or others in their environment to the extent that their urgent need for treatment in a closed institution is evident. Certain states allow involuntary hospitalization when patients are unable to care for themselves adequately.

The doctrine of parens patriae allows the state to intervene and to act as a surrogate parent for those who are unable to care for themselves or who may harm themselves. In English common law, parens patriae (“father of his country”) dates to the time of King Edward I and originally referred to a monarch’s duty to protect the people. In US common law, the doctrine has been transformed into a paternalism in which the state acts for persons who are mentally ill and for minors.

The statutes governing hospitalization of persons who are mentally ill generally have been designated commitment laws, but psychiatrists have long considered the term to be undesirable. Commitment legally means a warrant for imprisonment. The American Bar Association and the American Psychiatric Association have recommended that the term commitment be replaced by the less offensive and more accurate term hospitalization, which most states have adopted. Although this change in terminology does not correct the punitive attitudes of the past, the emphasis on hospitalization is in keeping with psychiatrists’ views of treatment rather than punishment.

Procedures of Admission

Four procedures of admission to psychiatric facilities have been endorsed by the American Bar Association to safeguard civil liberties and to make sure that no person is railroaded into a mental hospital. Although each of the 50 states has the power to enact its own laws on psychiatric hospitalization, the procedures outlined here are gaining much acceptance.

Informal Admission. Informal admission operates on the general hospital model, in which a patient is admitted to a psychiatric unit of a general hospital in the same way that a medical or surgical patient is admitted. Under such circumstances, the ordinary doctor–patient relationship applies, with the patient free to enter and to leave, even against medical advice.

Voluntary Admission. In cases of voluntary admission, patients apply in writing for admission to a psychiatric hospital. They may come to the hospital on the advice of a personal physician, or they may seek help on their own. In either case, patients are admitted if an examination reveals the need for hospital treatment. The patient is free to leave, even against medical advice.

Temporary Admission. Temporary admission is used for patients who are so senile or so confused that they require hospitalization and are not able to make decisions on their own and for patients who are so acutely disturbed that they must be admitted immediately to a psychiatric hospital on an emergency basis. Under the procedure, a person is admitted to the hospital on the written recommendation of one physician. After the patient has been admitted, the need for hospitalization must be confirmed by a psychiatrist on the hospital staff. The procedure is temporary because patients cannot be hospitalized against their will for more than 15 days.

Involuntary Admission. Involuntary admission involves the question of whether patients are suicidal and thus a danger to themselves or homicidal and thus a danger to others. Because these persons do not recognize their need for hospital care, the application for admission to a hospital may be made by a relative or a friend. After the application is made, the patient must be examined by two physicians, and if both physicians confirm the need for hospitalization, the patient can then be admitted.

Involuntary hospitalization involves an established procedure for written notification of the next of kin. Furthermore, the patients have access at any time to legal counsel, who can bring the case before a judge. If the judge does not think that hospitalization is indicated, the patient’s release can be ordered.

Involuntary admission allows a patient to be hospitalized for 60 days. After this time, if the patient is to remain hospitalized, the case must be reviewed periodically by a board consisting of psychiatrists, nonpsychiatric physicians, lawyers, and other citizens not connected with the institution. In New York State, the board is called the Mental Health Information Service.

Persons who have been hospitalized involuntarily and who believe that they should be released have the right to file a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. Under law, a writ of habeas corpus can be proclaimed by those who believe that they have been illegally deprived of liberty. The legal procedure asks a court to decide whether a patient has been hospitalized without due process of law. The case must be heard by a court at once, regardless of the manner or the form in which the motion is filed. Hospitals are obligated to submit the petitions to the court immediately.

RIGHT TO TREATMENT

Among the rights of patients, the right to the standard quality of care is fundamental. This right has been litigated in highly publicized cases in recent years under the slogan of “right to treatment.”

In 1966, Judge David Bazelon, speaking for the District of Columbia Court of Appeals in Rouse v. Cameron, noted that the purpose of involuntary hospitalization is treatment and concluded that the absence of treatment draws into question the constitutionality of the confinement. Treatment in exchange for liberty is the logic of the ruling. In this case, the patient was discharged on a writ of habeas corpus, the basic legal remedy to ensure liberty. Judge Bazelon further held that if alternative treatments that infringe less on personal liberty are available, involuntary hospitalization cannot take place.

Alabama Federal Court Judge Frank Johnson was more venturesome in the decree he rendered in 1971 in Wyatt v. Stickney. The Wyatt case was a class-action proceeding brought under newly developed rules that sought not release but treatment. Judge Johnson ruled that persons civilly committed to a mental institution have a constitutional right to receive such individual treatment as will give them a reasonable opportunity to be cured or to have their mental condition improved. Judge Johnson set out minimal requirements for staffing, specified physical facilities, and nutritional standards and required individualized treatment plans.

The new codes, more detailed than the old ones, include the right to be free from excessive or unnecessary medication; the right to privacy and dignity; the right to the least restrictive environment; the unrestricted right to be visited by attorneys, clergy, and private physicians; and the right not to be subjected to lobotomies, electroconvulsive treatments, and other procedures without fully informed consent. Patients can be required to perform therapeutic tasks but not hospital chores unless they volunteer for them and are paid the federal minimum wage. This requirement is an attempt to eliminate the practice of peonage, in which psychiatric patients were forced to work at menial tasks, without payment, for the benefit of the state.

In a number of states today, medication or electroconvulsive therapy cannot be forcibly administered to a patient without first obtaining court approval, which may take as long as 10 days.

RIGHT TO REFUSE TREATMENT

The right to refuse treatment is a legal doctrine that holds that, except in emergencies, persons cannot be forced to accept treatment against their will. An emergency is defined as a condition in clinical practice that requires immediate intervention to prevent death or serious harm to the patient or another person or to prevent deterioration of the patient’s clinical state.

In the 1976 case of O’Connor v. Donaldson,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree