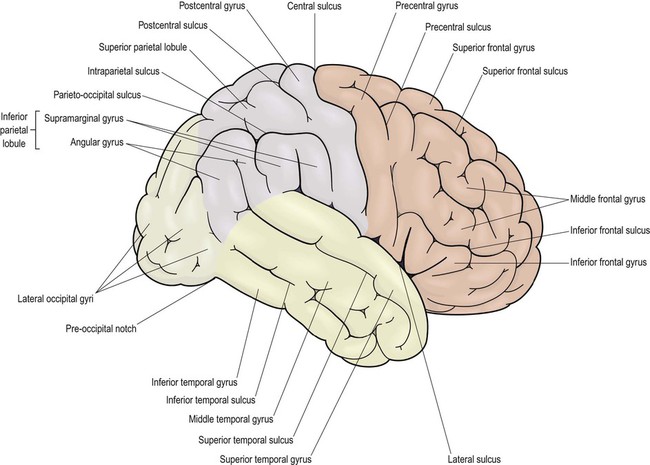

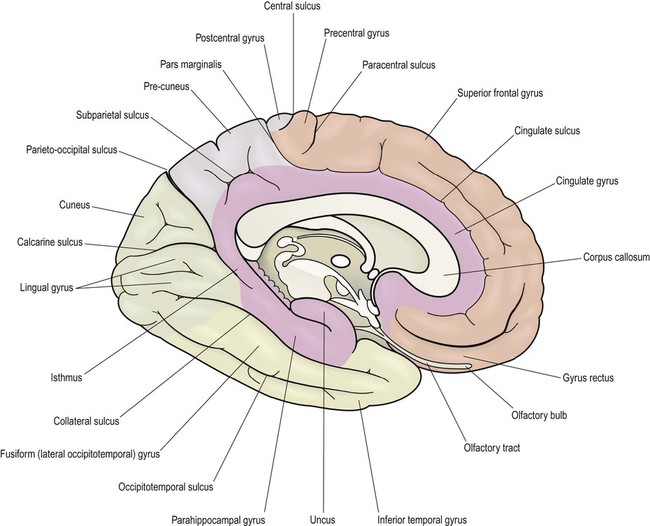

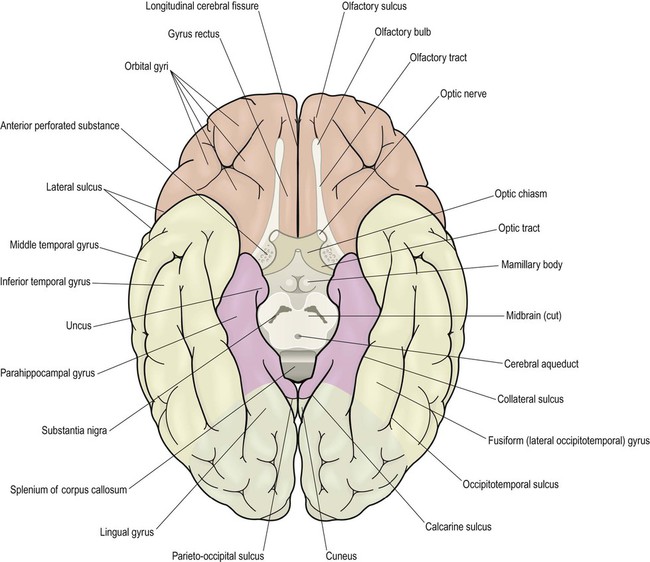

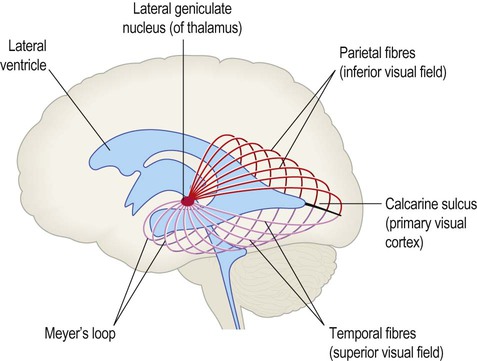

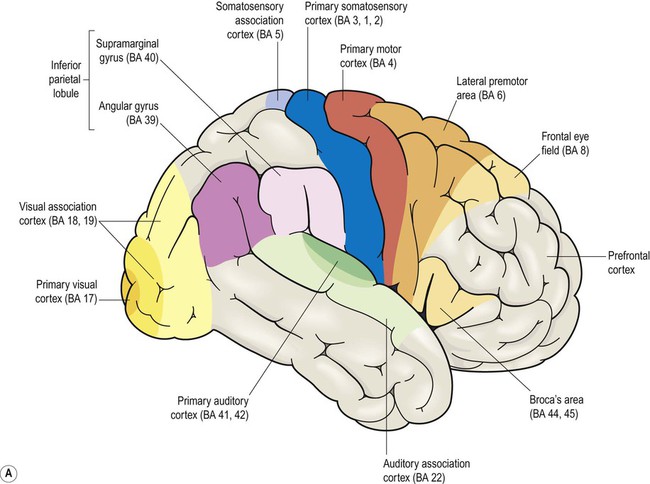

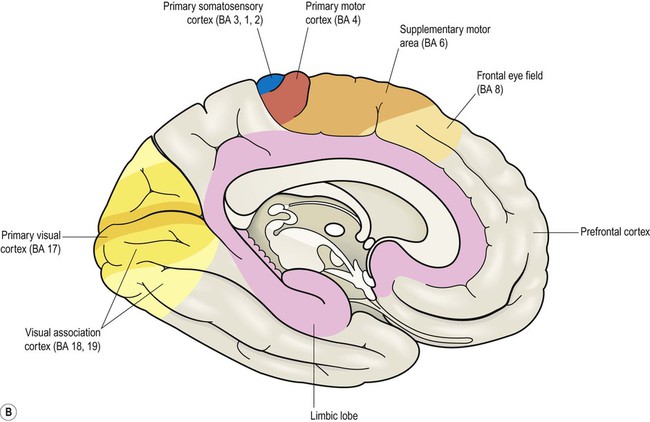

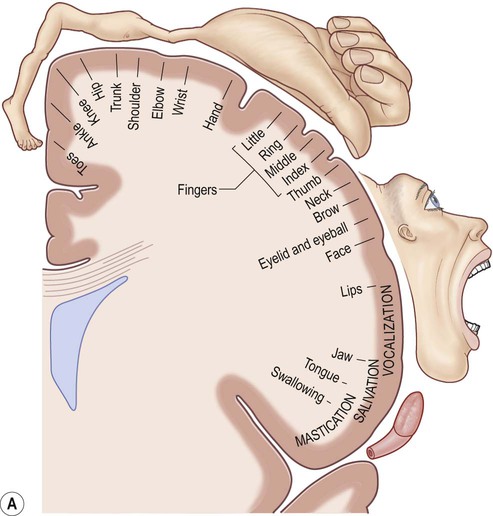

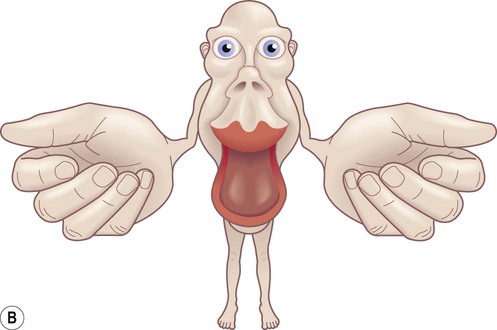

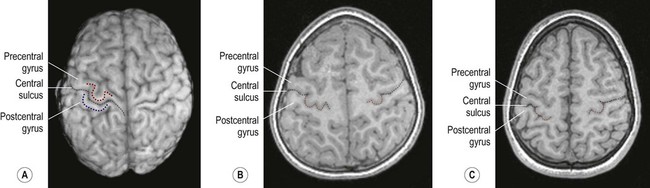

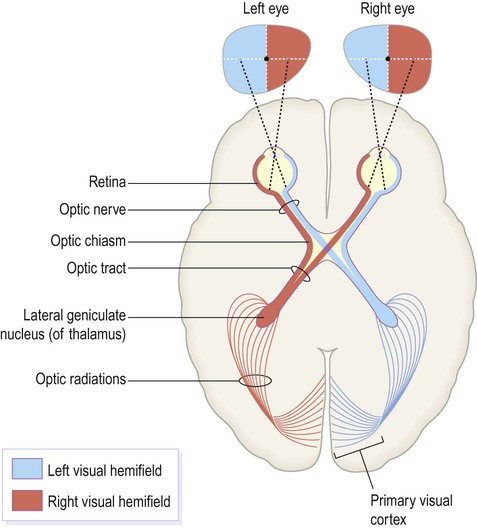

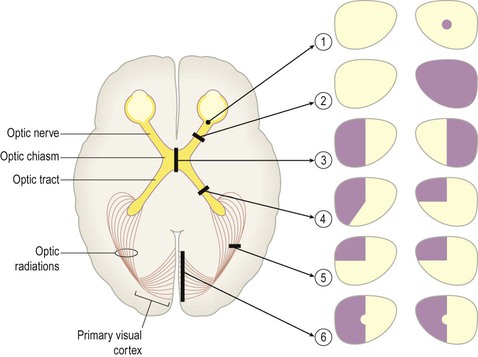

This chapter examines the functional anatomy of the brain, focusing on the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, hippocampus and amygdala. The main functional divisions of the thalamic region, brain stem and cerebellum are also discussed. Sensory and motor pathways of the CNS are described in Chapter 4. The blood supply to the brain is discussed in Chapter 10, in the context of stroke. This section describes the gyri and sulci of the cerebral hemispheres (Figs 3.1–3.3) and the main functional areas of the cerebral cortex (Fig. 3.4). Brodmann areas (BA) are indicated in brackets if they have important functional or clinical associations (these are numbered cortical regions, defined by microscopic differences in the structure of the cerebral cortex; see Chapter 5). The precentral gyrus ribbons forward over the cerebral convexity, immediately anterior to the central sulcus. It corresponds to the primary motor cortex (BA 4) which contains an inverted, point-to-point or somatotopic map of the opposite half of the body (Greek: soma, body; topos, place). The representation of each body part in the motor strip is proportional to the precision of movement control. This means that the areas for the hands, face and tongue are disproportionately large (Fig. 3.5). A useful landmark for identifying the motor cortex is the motor hand area which resembles an inverted capital omega (Fig. 3.6). The supplementary motor area (SMA) is just in front of the paracentral lobule. It contains a map of both sides of the body and tends to be recruited with its counterpart in the opposite hemisphere (e.g. when the hands are working together to manipulate an object). In contrast to the lateral premotor area, the SMA (or ‘medial premotor area’) is particularly concerned with internally generated (self-initiated) actions, rather than those that occur in response to an external event. The SMA is underactive in Parkinson’s disease, in which voluntary movements are initiated with effort and performed slowly (Ch. 13). Just anterior to the SMA, there is a small medial extension of the frontal eye field. The prefrontal cortex includes Broca’s area (discussed below, in the context of language) and the frontal eye fields (see above). The effects of prefrontal cortex lesions are discussed in Clinical Box 3.1. The remainder of the lateral parietal lobe is divided into superior and inferior parietal lobules by the intraparietal sulcus. This is a deep cleft at right angles to the central sulcus. The somatosensory association cortex (BA 5) is a small area in the superior parietal lobule, just behind the sensory strip. Lesions here may lead to astereognosia: the inability to recognize objects by touch (Greek: a-, without; stereos, solid; gnosis, knowledge). The posterior parietal cortex (BA 7) has close links with the occipital lobe and is concerned with visuospatial perception and attention (Clinical Box 3.2). This includes the representation and manipulation of objects (e.g. using a knife and fork) and the perception of movement (e.g. judging the approach of a moving vehicle). Certain semi-automatic movements are initiated by projections from the parietal cortex to the lateral premotor area (Clinical Box 3.3). The central visual pathways are crossed. This means that the right visual field is represented in the left occipital lobe and vice versa. Since light travels in straight lines and enters the eye via the small aperture of the pupil, objects in the right visual field project to the left half of each retina (coloured red in Fig. 3.7). Axons originating from the left half of each retina must therefore project to the left cerebral hemisphere. For this to happen, nerve fibres from the inner half of the retina must cross the midline to enter the opposite optic tract. This takes place at the optic chiasm, named for its resemblance to the Greek letter chi. Visual information is segregated into three separate ‘channels’ (concerned with form, motion and colour) by the primary visual cortex (V1) and visual association cortices (V2, V3… and higher). Two parallel visual ‘streams’ dealing with different aspects of visual perception arise from the occipital lobe. The dorsal or parietal lobe stream is concerned with the location and movement of objects and their positions relative to the body (the ‘where’ pathway). The ventral or temporal lobe stream synthesizes information about form and colour, allowing objects to be recognized (the ‘what’ pathway). Central visual pathway lesions are discussed in Clinical Box 3.4. On the inferior aspect of the hemisphere, the occipital and temporal lobes form a continuous, uninterrupted surface that is composed of the medial and lateral occipitotemporal gyri. The medial occipitotemporal gyrus is medial to the collateral sulcus. The portion lying within the occipital lobe is also known as the lingual gyrus, whereas the part contained in the temporal lobe is the parahippocampal gyrus. The lateral occipitotemporal gyrus runs alongside, between the collateral sulcus medially and occipitotemporal sulcus laterally. The anterior and posterior ends of the lateral occipitotemporal gyrus are usually tapered to give it a ‘spindle’ shape. It is therefore also known as the fusiform gyrus (Latin: fusiform, shaped like a spindle). It receives projections from the occipital lobe (part of the ‘what pathway’) and appears to be involved in the recognition of complex visual patterns. It contributes to reading (in the language-dominant hemisphere) and face recognition (in the non-dominant hemisphere) (Clinical Box 3.5).

Functional neuroanatomy

Cerebral cortex

Brodmann areas are indicated in brackets (apart from the prefrontal cortex and limbic lobe, which are large regions that incorporate numerous cortical functional zones).

Frontal lobe

Lateral aspect (Figs 3.1 and 3.4A)

(A) The motor strip contains an orderly somatotopic (point-to-point) representation of the contralateral half of the body, from the toes (medially) to the face and tongue (laterally). The size of the cortical representation for each body part reflects the precision of motor control, so that the areas for the hands, face and tongue are disproportionately large; (B) This can be represented graphically as a ‘homunculus’. Adapted from Matthew Levy, Bruce Koeppen, Bruce Stanton: Berne & Levy Principles of Physiology 4e (Mosby 2006) with permission.

(A) On the superior surface of the brain, the convolution corresponding to the ‘hand area’ of the primary motor cortex often resembles an inverted capital omega (Ω) as shown here in a surface rendering of the brain (obtained from a volumetric MRI scan). The motor hand area (in the precentral gyrus) is indicated by the red dashed line. The sensory hand area (of the postcentral gyrus) is shown in blue; (B) In axial sections (in this case, a T1-weighted MRI scan in the same individual) the ‘hand area’ of the primary motor cortex can be seen projecting backwards (red dashed line). Its shape often resembles a door-knob, as seen on the right-hand side in this individual; (C) Another example (in a different person). [Note: it is more common for the ‘hand-knob’ to be single (Ω-shaped) rather than double (ω-shaped).] Courtesy of Dr Gemma Northam.

Medial aspect (Figs 3.2 and 3.4B)

Prefrontal cortex (Figs 3.3 and 3.4)

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is concerned with organizing and planning behaviour in pursuit of short-, medium- and long-term goals.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is concerned with organizing and planning behaviour in pursuit of short-, medium- and long-term goals.

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) has a predominantly inhibitory role, preventing inappropriate behaviour (e.g. during social interactions) and facilitating moderation, restraint and tact.

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) has a predominantly inhibitory role, preventing inappropriate behaviour (e.g. during social interactions) and facilitating moderation, restraint and tact.

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is concerned with mood, motivation and emotion. It is part of the so-called ‘default network’ of the brain (areas that are active during quiet contemplation).

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is concerned with mood, motivation and emotion. It is part of the so-called ‘default network’ of the brain (areas that are active during quiet contemplation).

Parietal lobe

Lateral aspect (Figs 3.1 and 3.4A)

Central visual pathways (Figs 3.7 and 3.8)

The visual fields of each eye are illustrated separately in this figure, but in reality they overlap extensively to allow for binocular vision (and contributing to depth perception).

The optic chiasm (Fig. 3.7)

The primary visual cortex

The effects of lesions in various parts of the central visual pathway are illustrated. The visual fields of the left and right eyes are shown in pale yellow and the areas of reduced or absent vision are shown as purple shading. [The defects depicted are as follows: (1) = small scotoma (blind spot) in the right eye; (2) = monocular blindness, right eye; (3) = bitemporal hemianopia or ‘tunnel vision’; (4) = heteronymous left-sided field defect; (5) = left superior quadrantanopia, homonymous field defect; (6) = left hemianopia with macular (central) sparing.]

Temporal lobe

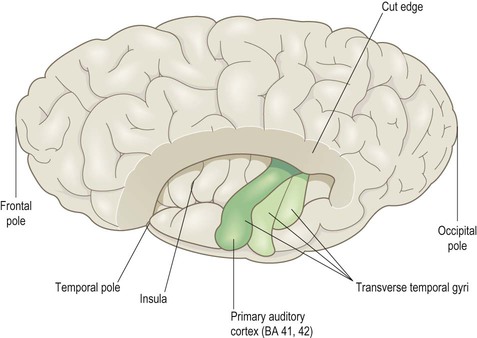

Superior aspect (Fig 3.10)

This view shows the superolateral aspect of the left cerebral hemisphere with the frontal and parietal opercula dissected away to reveal the superior surface of the temporal lobe (including the transverse temporal gyri and primary auditory cortex). Part of the insula can also be seen.

Inferior aspect (Fig. 3.3)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Functional neuroanatomy

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue