General Factors

There is a large literature on the possible causes of conversion disorder/hysteria. It approaches the problem from a variety of perspectives: psychoanalytic, psychogenic, cultural, and biologic. However, the fundamental problem with these general approaches is that they make the assumption that all patients presenting with symptoms imitating neurologic disease have the same disorder (

23,

24). Until the validity of grouping together patients with different pseudoneurologic symptoms can be established, it seems more sensible to study patients defined by sharing specific symptoms.

There has been only one controlled study that has addressed the etiology of functional paralysis and none in patients with functional sensory symptoms. There have, however, been several studies of wider groups of patients that have contained high proportions of patients with paralysis or sensory loss (

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32).

Binzer et al. carried out a prospective case control study of 30 patients with functional paralysis and 30 patients with neurologic paralysis (

8,

33,

34). They found a higher rate of so-called axis 1 psychiatric disorders (such as depression) as well as axis 2 disorders (personality disorders) in the functional paralysis group. They also found that functional paralysis patients tended to have received less education and to have experienced more negatively perceived life events prior to symptom onset. Contrary to many other studies of conversion disorder (

26), they did not find a higher rate of childhood abuse in the cases, although the cases did report their upbringing to be more negative (

34). A study of illness beliefs in the same cases and controls was remarkable for showing that patients with motor conversion symptoms were more likely to be convinced that they had a disease and to reject psychological explanations than were patients who actually had a neurologic disease.

Other studies have examined patients with conversion disorder, a high proportion of whom have paralysis. They have confirmed the importance of childhood factors, psychiatric comorbidity, personality variables, and the importance of organic disease as risk factors for functional symptoms.

The problem remains that all of these studies, although relatively specific to patients with functional paralysis, are still examining questions relating to the generality of why people might develop symptoms unexplained by disease. Childhood factors, psychiatric morbidity, disease, and personality factors are relevant to the development of many

kinds of functional somatic symptoms, and for that matter, depression and anxiety (

35). What researchers have found much harder to tackle is the specific question, “Why do people develop paralysis and not some other symptom?”

Why Do People Develop Paralysis?

The Psychodynamic Perspective

For the last century, the dominant view of the etiology of functional paralysis has been psychodynamic.

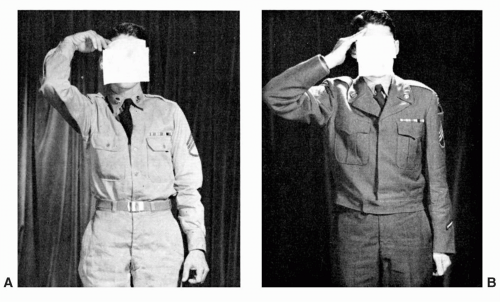

Figure 13.1 shows a classic case of a soldier who has lost the ability to perform his duties because of paralysis of the right hand. He complained, “I cannot salute and I cannot handle a gun with this hand; it has to be treated.”

Figure 13.1A shows the patient at presentation and

Figure 13.1B after psychotherapeutic treatment.

According to the psychodynamic model, the loss of function implicit in paralysis is said to arise as a result of mental conflict in a vulnerable individual—the mental conflict being partially or even completely resolved by the expression of physical symptoms—so-called primary gain. In addition to communicating distress that cannot be verbalized and “escaping” the conflict, the individual receives the status and advantage of being regarded as an invalid—so-called secondary gain. Some have regarded conversion hysteria purely as a form of communication. In the case of paralysis, the symptom may be regarded as communicating a conflict over action, for example, a pianist who cannot move his or her fingers. In the case shown in

Figure 13.1, the potential symbolism of the loss of the saluting hand is obvious.

While the hypothesis that conversion results from a transformation of distress into physical symptoms is clinically plausible for some patients, it remains merely a hypothesis. The evidence is that most patients have obvious “unconverted,” emotional distress as demonstrated by a number of studies which have found greater prevalence of emotional disorder in patients with functional symptoms compared to controls with an equivalently disabling symptom caused by disease (

8). Further evidence against the conversion hypothesis is the poor sensitivity and specificity of la belle indifférence as a clinical sign (see below). When emotional distress is apparently hidden, it is often the case that the patient is not

unaware of their emotional symptoms; rather, they simply

do not want to tell a doctor about them for fear of being labeled as mentally ill. Wessely (

36) has made a cogent plea for revision of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria to a more practical and theoretic symptom-based classification which would entail removing the name “Conversion Disorder.” In our view, this would be a great step forward, although it would be wrong to abandon all of the things we have learned from psychodynamic theory in doing so.

The Psychogenic Perspective and Dissociation

Ross Reynolds (

37), Charcot (

38), and others observed more than a century ago that ideas and suggestion could play a central role in the formation of particular symptoms. Janet extended this notion further with the idées fixes and dissociation (

39). Here is a famous example:

A man traveling by train had done an imprudent thing: While the train was running, he had got down on the step in order to pass from one door to the other, when he became aware that the train was about to enter a tunnel. It occurred to him that his left side, which projected, was going to be knocked slantwise and crushed against the arch of the tunnel. This thought caused him to swoon away but happily for him, he did not fall on the track, but was taken back inside the carriage, and his left side was not even grazed. In spite of this, he had a left hemiplegia (

39).

Janet referred to the principle process in hysteria as a “retraction of the field of personal consciousness and a

tendency to the dissociation and emancipation of the system of ideas and functions that constitute personality.” In the example above, the idea of paralysis, brought on by terror of an imminent injury, has become dissociated from the patient’s consciousness and is acting independently. He was keen to point out, however, that it is not necessarily the idea itself that is the cause of the symptom, but the action of that idea on a biologically and psychologically vulnerable individual. His conception of the idées fixes was also more sophisticated than “I’m paralyzed” or “I’m numb.” He thought in many cases the idées fixes could be something less immediately related to the symptom, for example, the fixed idea of a mother’s death or the departure of a spouse.

Surprisingly, there has been little systematic work since the efforts of Janet (

39) that has examined the phenomenon of dissociation in patients with functional paralysis, even though dissociation assumes the role of a principal etiologic factor in the

International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) classification. Two studies by Roelofs et al. found relationships between somatic and cognitive aspects of dissociation, hypnotisability, and child abuse in a cohort most of whom had functional motor symptoms (

26,

40). More work is needed in this area, specifically controlled data, and studies looking at dissociation as a transient trigger of symptoms rather than a general trait.

The Social Perspective

A social perspective on the generation and shaping of functional paralysis can also be advanced (

41). It has been suggested that patients respond to social pressures and expectations by choosing, consciously or subconsciously, to present with certain symptoms. The symptoms of paralysis may be chosen because it is a more culturally accepted presentation of ill health than is depression. This idea is supported by studies finding greater disease conviction among patients with functional paralysis compared to neurologic controls (

33). A strong belief in, or less often fear of a disease, is a recurring theme in this patient group. However, in our experience, the conviction that, whatever it is, it is “not a psychological problem” is even more prevalent and may reflect socially determined stigma about psychological problems. The social dimension of hysterical paralysis is explored further in Shorter’s book

From Paralysis to Fatigue (

42), although his hypothesis that paralysis is “now a rare symptom and seen mostly in ‘backward’ working-class and rural patients” (

43) requires revision in light of more recent studies.

The Biologic Perspective

For decades, researchers have been sporadically searching for biologic correlates of functional paralysis or sensory loss. Only with the advent of functional neuroimaging is this avenue proving fruitful, although studies thus far remain preliminary.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Eleven studies and case reports (

17,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53) with a total of 73 patients have used transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to test motor function in patients with functional paralysis. Almost without exception they have reported normal findings. This suggests that TMS may be a useful adjunct in distinguishing neurologic from functional weakness. Two papers have described therapeutic benefit from diagnostic (

50) and repetitive TMS (

54), although one suspects the mechanism here is primarily persuasion that recovery is possible rather than anything specific to TMS itself.

Evoked Responses and the P300 Response

An early study of functional hemianesthesia suggested that patients may have impaired standard evoked sensory responses in their affected limbs (

55), but this was refuted by several even earlier (

56) and later studies (

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62) including a recent study using magnetoencephalography (

63). Most recently transiently absent scalp somatosensory evoked responses have been seen in two patients with conversion disorder that subsequently recovered (

64).

Of greater interest are the nature of the P300 and other late components of the evoked response in patients with functional sensory loss. One study found that it was diminished in one case of unilateral functional sensory loss but not in a subject feigning sensory loss (

65), and another found reduction in P300 components in patients with hypnotically induced sensory loss (

66).

Cognitive Neuropsychology

Two older studies (both with around ten patients each) found that patients with conversion symptoms had reduced habituation compared to ten controls with anxiety, suggesting an impairment in attention (

67,

68). These studies found different degrees of physiologic arousal detectable in patients with conversion symptoms compared to controls. Another study suggested that arousal was high even when la belle indifférence was present (

69). A series of studies in this area by Roelofs et al. have suggested deficits in higher level central initiation of movement with relative preservation of lower level motor execution (as measured, e.g., by reaction times) in patients with functional paralysis (

70,

71). Detailed studies of attention in this patient group have been consistent with a high-level voluntary attentional deficit (

72). Spence has argued that functional paralysis is a disorder of action, drawing analogies with other disorders, including depression and schizophrenia (

73).

Functional Imaging

Charcot spent many years later in his career applying the clinicoanatomic method to hysteria. He believed that there must be a dynamic lesion in the brain to explain the symptoms he was observing. The small body of work on the

functional neuroimaging of hysteria that is now able to look for such a dynamic lesion is presented elsewhere in this symposium. The studies published in relation to the symptom of paralysis and sensory loss are summarized in

Table 13.3 below.

The data so far published is conflicting. This is perhaps not surprising and was acquired from different experimental paradigms. It is discussed further in

Chapter 26.

At their best, newer studies based in cognitive neuroscience are leading the way to a more integrated cognitive neuropsychiatric approach to the problem of functional paralysis with a focus on mechanism rather than cause. But although these studies challenge conventional psychogenic models of causation, a purely biologic interpretation of this data is just as unsatisfactory as a purely psychogenic theory of hysterical paralysis.

The Importance of Panic, Dissociation, Physical Injury, or Pain at Onset

Little attention has been paid to the circumstances and symptoms surrounding the onset of functional paralysis. In our experience, the circumstances around onset reported by individual patients provide intriguing clues to the possible mechanisms behind functional paralysis. We tend to think of paralysis, unlike abdominal bloating, as a symptom outside everyday experience and normal physiology. Yet paralysis occurs in all of us during REM sleep, when we are terrified, when we are tired and our limbs feel like lead, or as a very transient protective response when we experience acute pain in a limb. Is it possible that some of these more “everyday” causes of transient paralysis are acting as triggers to more long-lasting symptoms?

Panic and Dissociation

When given in-depth interviews, many patients reluctantly report symptoms of panic just before the onset of functional paralysis. Specifically, they may report that they became dizzy, (by which they often mean the dissociative symptoms of depersonalization or derealization), and autonomic symptoms such as sweating, nausea, and breathing difficulties. Sometimes the patient either refuses to volunteer or genuinely didn’t experience fear in association with other autonomic symptoms—so called “panic without fear” (

83). This idea is not new. Savill comments on it in his 1909 book (

84) extending the range of attack types at onset to include nonepileptic seizures, something we have also seen:

If the patient is under careful observation at the time of onset, it will generally be found that cases of cerebral paresis, rigidity or tremor are actually initiated, about the time of onset, by a more or less transient hysterical cerebral attack.…

Affirmative evidence on this point is not always forthcoming unless the patient was at the time under observation, or is himself an intelligent observer. I found affirmative evidence of this point in 47/50 cases of hysterical motor disorder which I investigated particularly. Sometimes there was only a “swimming” in the head, or a slight syncopal or vertiginous attack, slight confusion of the mind, or transient loss of speech, but in quite a number there was generalized trepidation or convulsions (

84).

Hyperventilation

Hyperventilation may also occur at the onset of symptoms, either alone or in combination with panic and dissociation. The link between hyperventilation and unilateral sensory symptoms is well-established clinically (

85,

86) and experimentally (

87), but the mechanism for this remains in doubt as both central and peripheral factors may be responsible (

88).

Physical Injury

Careful reading of the numerous case reports of functional paralysis indicates a large number of cases arising after a physical injury rather than a primarily emotional or psychological shock (although, clearly, physical injury is itself an emotional trauma). The relevance of physical trauma, and its psychological correlates, in precipitating hysteria in vulnerable individuals was well-understood by clinicians, such as Charcot (

89), Page (

90), Fox (

91), and Janet (

39), in the late 19th and early 20th century. Subsequently, trauma and shock acquired a much more psychological flavour, and the possibility that simple physical injury, even of a trivial nature, could be enough in itself to produce hysterical symptoms has been lost (although interestingly, similar debate continues with respect to whiplash injury and reflex sympathetic dystrophy).

Pain

A trivial injury could trigger functional paralysis because of panic, dissociation, or hyperventilation as described above. But pain does not have to cause a shock to cause symptoms. It is well-established that pain in itself causes a degree of weakness, which can be overcome only with effort (

92). Motor symptoms (predominantly weakness) are prominent in case series of reflex sympathetic dystrophy and complex regional pain. In one case series, 79% of 145 patients described weakness, mostly of the give-way variety, and 88% sensory disturbance (

93). When sensory signs and symptoms are sought they seem to be remarkably common in patients with chronic pain (

94). Ochoa and Verdugo (

95,

96) have produced convincing evidence that much of the sensory disturbance and movement disorder seen in complex regional pain is clinically identical to that seen in functional or psychogenic disorders. In one study of 27 patients with complex regional pain syndrome type 1 and sensory symptoms, 50% of the patients had complete reversal of their hypoaesthesia with placebo compared to none out of 13 patients with a nerve injury (

95).

Other Pathways

There are many other pathways to the development of functional paralysis. We have seen patients who develop functional paralysis after surgery (who simultaneously experienced intense depersonalization as they came out of the anesthetic), and several whose first experience of paralysis was an episode of undiagnosed sleep paralysis precipitated by depression and insomnia that later snowballed into more permanent nonsleep-related symptoms. Perhaps one of the commonest routes to functional paralysis is that of a patient with mild chronic fatigue or pain who then becomes aware of an asymmetry of symptoms. Either for biologic reasons or for attentional reasons (but probably because of both), this asymmetry escalates over weeks and months until it appears more dramatically unilateral.

These are hypotheses regarding onset and they require testing. They could, however, open a window on the proximal mechanisms of functional paralysis.

Etiology—Conclusions

Functional paralysis is a symptom, like headache or fatigue, which almost certainly has multiple causes. Some predisposing factors, like childhood neglect, are nonspecific and apply to many illnesses; others such as dissociation are perhaps more specific to pseudoneurologic symptoms. Similarly, stress and emotional disorder may be nonspecific precipitating factors, whereas pain or sleep paralysis and the asymmetry of the brain’s functioning in emotional disorder and panic may be more specific triggers. Illness beliefs, such as a belief or fear of stroke, are probably just one of many factors that can play a role in perpetuating the specific symptom of paralysis. Neuroimaging and other biologic approaches may prove helpful in increasing our understanding of the neural mechanisms of functional paralysis. It seems likely that there are a variety of different factors that lead to the development of an apparently identical symptom and that these may differ among patients.