Gender Dysphoria

The term gender dysphoria appears as a diagnosis for the first time in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) to refer to those persons with a marked incongruence between their experienced or expressed gender and the one they were assigned at birth. It was known as gender identity disorder in the previous edition of DSM.

The term gender identity refers to the sense one has of being male or female, which corresponds most often to the person’s anatomical sex. Persons with gender dysphoria express their discontent with their assigned sex as a desire to have the body of the other sex or to be regarded socially as a person of the other sex.

The term transgender is a general term used to refer to those who identify with a gender different from the one they were born with (sometimes referred to as their assigned gender). Transgender people are a diverse group: There are those who want to have the body of another sex known as transsexuals; those who feel they are between genders, of both genders, or of neither gender known as genderqueer; and those who wear clothing traditionally associated with another gender, but who maintain a gender identity that is the same as their birth-assigned gender known as crossdressers. Contrary to popular belief, most transgender people do not have genital surgery. Some do not desire it and others who do may be unable to afford it. Transgender people may be of any sexual orientation. For example, a transgender man, assigned female at birth, may identify as gay (attracted to other men), straight (attracted to women), or bisexual (attracted to both men and women).

In DSM-5, no distinction is made for the overriding diagnostic term gender dysphoria as a function of age. However, criteria for diagnosis in children or adolescents are somewhat different. In children, gender dysphoria can manifest as statements of wanting to be the other sex and as a broad range of sex-typed behaviors conventionally shown by children of the other sex. Gender identity crystallizes in most persons by age 2 or 3 years. A specifier is noted if the gender dysphoria is associated with a disorder of sex development.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Children

Most children with gender dysphoria are referred for clinical evaluation in early grade school years. Parents, however, typically report that the cross-gender behaviors were apparent before 3 years of age. Among a sample of boys younger than age 12 who were referred for a range of clinical problems, the reported desire to be the other sex was 10 percent. For clinically referred girls younger than age 12, the reported desire to be the other sex was 5 percent. The sex ratio of children referred for gender dysphoria is 4 to 5 boys for each girl, which is hypothesized to be due in part to societal stigma directed toward feminine boys. The sex ratio is equal in adolescents referred for gender dysphoria. Researchers have observed that many children considered to have shown gender nonconforming behavior do not grow up to be transgender adults; conversely many people who later come out as transgender adults report that they were not identified as gender nonconforming during childhood.

Adults

The estimates of gender dysphoria in adults emanate from European hormonal/surgical clinics with a prevalence of 1 in 11,000 male-assigned and 1 in 30,000 female-assigned people. DSM-5 reports a prevalence rate ranging from 0.005 to 0.014 percent for male-assigned and 0.002 to 0.003 percent for female-assigned people. Most clinical centers report a sex ratio of three to five male patients for each female patient. Most adults with gender dysphoria report having felt different from other children of their same sex, although, in retrospect, many could not identify the source of that difference. Many report feeling extensively cross-gender identified from the earliest years, with the cross-gender identification becoming more profound in adolescence and young adulthood. Overall the prevalence of male to female dysphoria is higher than female to male dysphoria. An important factor in diagnosis is that there is greater social acceptance of birth-assigned females dressing and behaving as boys (so-called tomboys) than there is of birth-assigned males acting as females (so-called sissies). Some researchers speculate that one in 500 adults may fall somewhere on a transgender spectrum, based on population data rather than clinical data.

ETIOLOGY

Biological Factors

For mammals, the resting state of tissue is initially female; as the fetus develops, a male is produced only if androgen (set off by the Y chromosome, which is responsible for testicular development) is introduced. Without testes and androgen, female external genitalia develop. Thus, maleness and masculinity depend on fetal and perinatal androgens. Sexual behavior in lower animals is governed by sex steroids, but this effect diminishes as the evolutionary tree is scaled. Sex steroids influence the expression of sexual behavior in mature men or women; that is, testosterone can increase libido and aggressiveness in women, and estrogen can decrease libido and aggressiveness in men. But masculinity, femininity, and gender identity may result more from postnatal life events than from prenatal hormonal organization.

Brain organization theory refers to masculinization or feminization of the brain in utero. Testosterone affects brain neurons that contribute to the masculinization of the brain in such areas as the hypothalamus. Whether testosterone contributes to so-called masculine or feminine behavioral patterns remains a controversial issue.

Genetic causes of gender dysphoria are under study but no candidate genes have been identified, and chromosomal variations are uncommon in transgender populations. Case reports of identical twins have shown some pairs that are concordant for transgender issues and others not so affected.

A variety of other approaches to understanding gender dysphoria are underway. These include imaging studies that have shown changes in white matter tracts, cerebral blood flow, and cerebral activation patterns in patients with gender dysphoria; but such studies have not been replicated. An incidental finding is that transgender persons are likely to be left handed, the significance of which in unknown.

Psychosocial Factors

Children usually develop a gender identity consonant with their assigned sex. The formation of gender identity is influenced by the interaction of children’s temperament and parents’ qualities and attitudes. Culturally acceptable gender roles exist: Boys are not expected to be effeminate, and girls are not expected to be masculine. There are boys’ games (e.g., cops and robbers) and girls’ toys (e.g., dolls and dollhouses). These roles are learned, although some investigators believe that some boys are temperamentally delicate and sensitive and that some girls are aggressive and energized—traits that are stereotypically known in today’s culture as feminine and masculine, respectively. However, greater tolerance for mild cross-gender activity in children has developed in the last few decades.

Sigmund Freud believed that gender identity problems resulted from conflicts experienced by children within the Oedipal triangle. In his view, these conflicts are fueled by both real family events and children’s fantasies. Whatever interferes with a child’s loving the opposite-sex parent and identifying with the same-sex parent interferes with normal gender identity development.

Since Freud, psychoanalysts have postulated that the quality of the mother–child relationship in the first years of life is paramount in establishing gender identity. During this period, mothers normally facilitate their children’s awareness of, and pride in, their gender: Children are valued as little boys and girls. Analysts argue that devaluing, hostile mothering can result in gender problems. At the same time, the separation–individuation process is unfolding. When gender problems become associated with separation–individuation problems, the result can be the use of sexuality to remain in relationships characterized by shifts between a desperate infantile closeness and a hostile, devaluing distance.

Some children are given the message that they would be more valued if they adopted the gender identity of the opposite sex. Rejected or abused children may act on such a belief. Gender identity problems can also be triggered by a mother’s death, extended absence, or depression, to which a young boy may react by totally identifying with her—that is, by becoming a mother to replace her.

The father’s role is also important in the early years, and his presence normally helps the separation–individuation process. Without a father, mother and child may remain overly close. For a girl, the father is normally the prototype of future love objects; for a boy, the father is a model for male identification.

Learning theory postulates that children may be rewarded or punished by parents and teachers on the basis of gendered behavior, thus influencing the way children express their gender identities. Children also learn how to label people according to gender and eventually learn that gender is not dictated by surface appearance such as clothing or hairstyle.

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Children

The DSM-5 defines gender dysphoria in children as incongruence between expressed and assigned gender, with the most important criterion being a desire to be another gender or insistence that one is another gender (Table 18-1). By emphasizing the importance of the child’s self-perception, the creators of the diagnosis attempt to limit its use to those children who clearly state their wishes to be another gender, rather than encompassing a broader group of children who might be considered by adults to be gender nonconforming. However a child’s behavior may also lead to this diagnosis.

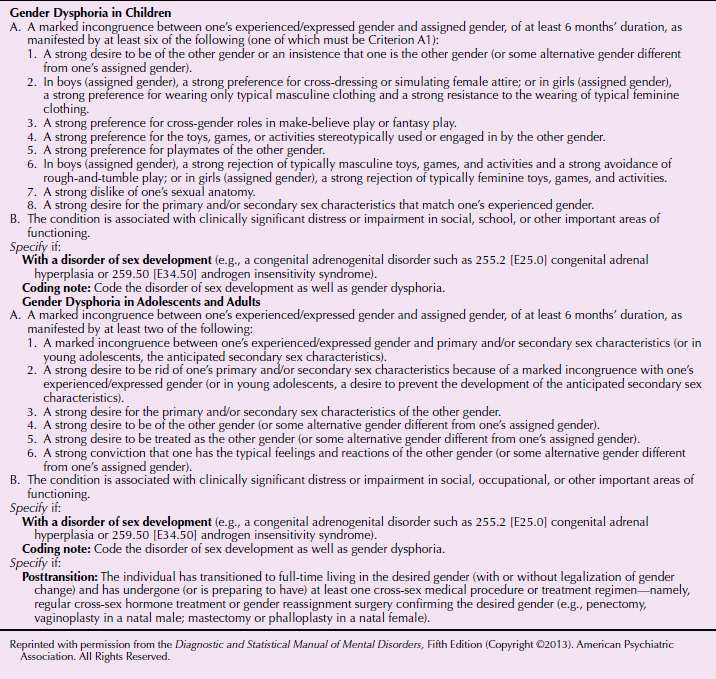

Table 18-1

Table 18-1

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Gender Dysphoria

Many children with gender dysphoria prefer clothing typical of another gender, preferentially choose playmates of another gender, enjoy games and toys associated with another gender, and take on the roles of another gender during play. For a diagnosis to be made, these social characteristics must be accompanied by other traits less likely to be socially influenced, such as a strong desire to be the other gender, dislike of one’s sexual anatomy, or desire for primary or secondary sexual characteristics of the desired gender. Children may express a desire to have different genitals, state that their genitals are going to change, or urinate in the position (standing or sitting) typical of another gender. It is notable that characteristics used to diagnose children with gender dysphoria must be accompanied by clinically significant distress or impairment on the part of the child, and not simply on the part of the adult caregivers, who may be uncomfortable with gender nonconformity.

Differential Diagnosis of Children

Children diagnosed with gender dysphoria, predicted to be more likely than others to identify as transgender as adults, are differentiated from other gender nonconforming children by statements about desired anatomical changes, as well as persistence of the diagnosis over time. Children whose gender dysphoria persists over time may make repeated statements about a desire to be or belief that they are another gender. Other gender nonconforming children may make these statements for short periods but not repeatedly, or may not make these types of statements, and may instead prefer clothing and behaviors associated with another gender, but show contentment with their birth-assigned gender.

The diagnosis of gender dysphoria no longer excludes intersex people, and instead is coded with a specifier in the cases where intersex people are gender dysphoric in relation to their birth-assigned gender. A medical history is important to distinguish between those children with intersex conditions and those without. The standards of care for intersex children have changed dramatically over the last few decades due to activism by intersex adults and supportive medical and mental health professionals. Historically, intersex babies were often subjected to early surgical procedures to create more standard male or female appearances. These procedures had the potential to cause sexual dysfunction, such as inability to orgasm, and permanent sterility. Recently, these practices have changed considerably so that more intersex people are given the chance to make decisions about their bodies later in life.

Adolescents and Adults

Adolescents and adults diagnosed with gender dysphoria must also show an incongruence between expressed and assigned gender. In addition, they must meet at least two of six criteria, half of which are related to their current (or in the cases of early adolescents, future) secondary sex characteristics or desired secondary sex characteristics. Other criteria include a strong desire to be another gender, be treated as another gender, or the belief that one has the typical feelings and reactions of another gender (see Table 18-1).

In practice, most adults who present to mental health practitioners with reports of gender-related concerns are aware of the concept of transgender identity. They may be interested in therapy to explore gender issues, or may be making contact in order to request a letter recommending hormone treatment or surgery. The cultural trope of being “trapped in the wrong body” does not apply to all, or even most, people who identify as transgender, so clinicians should be aware to use open and affirming approaches, taking language cues from their patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree