Gender Identity Disorder

Kenneth J. Zucker

Gender Identity Disorder

Definition

At a nascent cognitive level, gender identity has been defined as a child’s recognition that he or she is a member of one sex but not of the other (1). Four decades ago, Stoller (2) coined the term core gender identity to refer to the development of a “fundamental sense of belonging to one sex,” the awareness that one is a male or female. At an affective level, this sense of belonging is emotionally valued, so that a child experiences a sense of comfort or security from being a boy or a girl. A child’s gender identity is often closely tied to the adoption of culturally defined behavioral markers of masculinity or femininity (gender roles).

What does one observe in children and adolescents who meet the DSM-IV-TR criteria for gender identity disorder (GID)? The most salient feature is a strong identification with, and preference for, the gender role characteristics of the other sex. This can be inferred from various age-related behavioral manifestations of gender identification, such as toy interests, fantasy role and activity preferences, and peer affiliation preferences. Cross-gender identification is also expressed through verbal statements that one is, or would like to be, a member of the other sex. Moreover, children with GID often have few positive things to say about their own sex and appear to experience a sense of gender dysphoria, or unease, about their own sex. By adolescence, when the clinical picture more closely resembles what one observes in adults with GID, the pervasive sense of gender dysphoria becomes even more salient. Table 5.13.1 shows the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for GID.

TABLE 5.13.1 DSM-IV DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR GENDER IDENTITY DISORDER | ||

|---|---|---|

|

History

In the 1950s, two clinical developments led to an increased interest in the study of children with potential problems in their gender identity development. First, Money et al’s (3) research on children with various types of physical intersex conditions showed that a key milestone in gender identity formation occurred sometime between 18 and 36 months of age, if not earlier. Money et al. reported that, despite an ambiguous sexual biology, children with disorders of sex development (DSD) (4) could develop a stable gender identity if they were reared unambiguously as members of one sex or the other. Second, retrospective clinical reports on the adult syndrome of GID, commonly referred to as transsexualism (5), led to the recognition that the behavioral markers of this condition were often expressed during the first few years of life.

In the early 1980s, thinking about children with gender identity problems was influenced by a third development. A series of studies on homosexuality in adults, perhaps peaking with the volume by Bell et al. (6) indicated that a pattern of childhood cross-gender behavior was also a strong developmental predictor of later homosexuality, which was subsequently confirmed in a meta-analytic review by Bailey and Zucker (7). Over the past decade, increasing attention has been given to the identification of variation in the long-term developmental trajectories of children with GID (see Course and Prognosis).

Epidemiology

Prevalence

To my knowledge, none of the numerous contemporary epidemiological studies on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in children and youth have examined GID. Accordingly, estimates of prevalence have had to rely on less sophisticated approaches. For example, it has been suggested that one estimate of prevalence might be inferred from the number of persons attending clinics for adults that serve as gateways for hormonal and surgical sex reassignment. Because not all gender dysphoric adults may attend such clinics, this method may well underestimate the prevalence of GID; in any case, the number of adult transsexuals is small— one estimate from the Netherlands suggested a prevalence of 1 in 11,000 men and 1 in 30,400 women (8).

More liberal estimates of prevalence can be judged from studies of children in whom specific cross-gender behaviors have been assessed. For example, the standardization study of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (9), a widely used parent-report questionnaire of childhood behavioral psychopathology, included information on the percentage of mothers of both clinic-referred and nonreferred boys and girls who endorsed two items pertaining to cross-gender identification: “behaves like opposite sex” and “wishes to be of opposite sex.”

TABLE 5.13.2 PERCENTAGE OF U.S. NONREFERRED CHILDREN WHOSE MOTHERS ENDORSED CHILD BEHAVIOR CHECKLIST ITEMS RELEVANT TO CROSS-GENDER IDENTIFICATION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 5.13.2 shows the percentage of mothers of nonreferred boys and girls, across the age range of 4 to 11 years, who endorsed these two items by giving ratings of either a 1 (somewhat or sometimes true) or a 2 (very true or often true) on a 0- to 2-point scale for frequency of occurrence. For both items, more mothers of girls gave ratings of either a 1 or a 2 than did mothers of boys; however, chi-square tests showed that the differences were significant only for the rating of a 1 for the item “behaves like the opposite sex.” By maternal report, the percentage of both boys and girls who wished to be of the opposite sex was quite low (range, 0.0–2.5% by sex and intensity).

These findings were largely replicated in a recent large-scale study of Dutch twins (N = 23,393) at ages 7 and 10 (10). As shown in Table 5.13.3, at both ages and for both sexes, behaving like the opposite sex was more common than wishing to be of the opposite sex (ratings of 1 and 2 combined); in general, more girls than boys were rated as showing these behaviors. Again, the percentage of both boys and girls who wished to be of the opposite sex was quite low (range, 0.9–1.7% by sex and age).

Sex Differences in Referral Rates

Among children between the ages of 3–12, it has been found that boys are referred clinically more often than girls for concerns regarding gender identity. From one speciality clinic in Toronto, Canada, Cohen-Kettenis et al (11) reported a sex ratio of 5.8:1 (N = 358) of boys to girls based on consecutive referrals from 1975 to 2000.*. In this study, comparative data were available on children evaluated at the only gender identity clinic for children in Utrecht, The Netherlands. Although the sex ratio was significantly smaller at 2.9:1 (N = 130), it still favored referral of boys over girls.

Among adolescents between the ages of 13–20, however, the sex ratio in the Toronto clinic narrowed considerably, at 1.3:1 (N = 72) of males to females (12). This ratio was remarkably similar to that of 1.2:1 (N = 133) reported by Cohen-Kettenis and Päfflin (13) in the Netherlands. Thus, across both clinics, there was a sex-related skew in referrals

during childhood, but this lessened considerably during adolescence.

during childhood, but this lessened considerably during adolescence.

TABLE 5.13.3 PERCENTAGE OF DUTCH TWINS (7 AND 10 YEARS) WHOSE MOTHERS ENDORSED CHILD BEHAVIOR CHECKLIST ITEMS RELEVANT TO CROSS-GENDER IDENTIFICATION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How might this age-related developmental disparity in the sex ratio best be understood? One possibility is that it reflects accurately the change in prevalence of GID in males and females between childhood and adolescence, but because prevalence data from the general population are lacking, this remains a matter of conjecture. Another possibility is that social factors play a role. For example, in childhood, it is well established that parents, teachers, and peers are less tolerant of cross-gender behavior in boys than in girls, which might result in a sex differential in clinical referral (14).

Two studies provided data that supported this prediction, in which it was shown that girls may need to display more cross-gender behavior than boys before a referral is initiated 11,15. This higher threshold for referral appeared consistent with the fact that, in both the Toronto and Utrecht clinics, girls were referred, on average, about 10 months later than boys (M age, 8.1 years vs. 7.3 years, respectively), a significant difference, despite the fact that the girls showed, on average, higher levels of cross-gender behavior than the boys (11). However, it is important to note that the sexes did not differ in the percentage who met the complete DSM criteria for GID; thus, there was no gross evidence for a sex difference in false positive referrals.

Another factor that could affect sex differences in referral rates pertains to the relative salience of cross-gender behavior in boys vs. girls. For example, it has been long observed that the sexes differ in the extent to which they display sex-typical behaviors; when there is significant between-sex variation, it is almost always the case that girls are more likely to engage in masculine behaviors than boys are likely to engage in feminine behaviors (16). Thus, the base rates for cross-gender behavior, at least within the range of normative variation, may well differ between the sexes.

In adolescence, the picture may change considerably in that extreme cross-gender behavior is subject to more equivalent social pressures across sex and thus there is a lowering in the bias towards a greater referral of boys. Along similar lines, it is possible that gender dysphoria in adolescent girls is more difficult to ignore than it is during childhood, as the intensification of concerns with regard to physical sex transformation becomes more salient to parents and other adults involved in the life of the adolescent.

Age at Referral

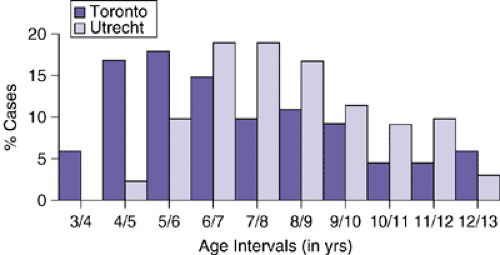

In the Cohen-Kettenis et al (11) study, the age distribution at referral showed some remarkable differences. It can be seen in Figure 5.13.1 that the Toronto sample had a substantially higher percentage of referrals between the ages of 3–4, 4–5, and 5–6 years than did the Utrecht sample (40.5% vs. 13.1%) and these differences were even more pronounced for the age intervals of 3–4 and 4–5 years (22.6% vs. 2.3%).

Cohen-Kettenis et al noted that the “delay” in referral to the Dutch clinic could not readily be accounted for by differences in natural history, including degree of cross-gender behavior, base rates of cross-gender behavior in the two countries, or financial factors (such as insurance coverage). It was speculated that cultural factors might account for the cross-national difference in age at referral, in that North American parents become concerned about their child’s cross-gender behavior at an earlier age than do Dutch parents.

Diagnosis and Clinical Features

The initial behavioral signs (age of onset) of GID most typically appear during the toddler and preschool years (17), the same developmental time period in which more conventional patterns of sex-typed behavior can also first be observed (18). The central clinical issue concerns the degree to which a pattern of behavioral signs is present, because this pattern is the basis for inference on the extent to which a child is cross-gender-identified and meets the DSM-IV-TR criteria for GID (Table 5.13.1).

For child patients, both the Toronto and Dutch clinics have reported that about 70% of their probands met the complete DSM criteria for GID at the time of assessment and the remainder were subthreshold for the diagnosis, i.e., they had some symptoms but not enough to meet the criteria for GID (11). In several quantitative studies, it has been shown that the subthreshold probands had patterns of cross-gender behavior that were intermediate between the threshold probands and controls 14,19, thus providing some validity evidence for clinician-based diagnosis of GID (20).

For patients seen for the first time in adolescence, however, the clinician needs to be aware of two major subgroups. The first subgroup consists of male and female youth who have a very clear childhood onset of GID, which has persisted into adolescence. Almost all of the youth in this subgroup have a homosexual sexual orientation, i.e., they are sexually attracted to members of their own birth sex (21). The second subgroup consists almost exclusively of males. These youth have a relatively “late onset” of GID, i.e., there is no clear indication of a childhood cross-gender history and the desire to be of the opposite sex is voiced only during the beginning of adolescence or even later 22,23. Many of these adolescent boys have a cooccurring clinical presentation of transvestic fetishism or autogynephilia (sexual arousal at the thought of being a female) (24). These youth often have a heterosexual, bisexual, or asexual sexual orientation.

Associated Behavior Problems

Comorbidity— the presence of two or more psychiatric disorders— occurs frequently among children referred for clinical evaluation. Assuming that the putative comorbid conditions actually represent distinct disorders, it is important to know, for various reasons, whether one condition increases the risk for the other condition or if the conditions are caused by distinct or overlapping factors (25).

Regarding GID, an interesting new example of comorbidity comes from several case reports describing its cooccurrence with Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD) 26,27,28. These case reports mesh with my own clinical experience, having systematically evaluated 10 boys with comorbid GID and PDD

over the past several years. One 6-year-old boy, for example, who had many of the classic features of PDD, including intense behavioral rigidity and obsessional preoccupations (e.g., with vacuum cleaners), had been insisting that he was a girl for the past 3 years and would introduce himself to other children using a girl’s name. He would have catastrophic temper tantrums if reminded that he was really a boy. It is, of course, highly unlikely that GID “causes” PDD or the other way round. Rather, it is conceivable that the relation between GID and PDD is linked by traits of behavioral rigidity and obsessionality.

over the past several years. One 6-year-old boy, for example, who had many of the classic features of PDD, including intense behavioral rigidity and obsessional preoccupations (e.g., with vacuum cleaners), had been insisting that he was a girl for the past 3 years and would introduce himself to other children using a girl’s name. He would have catastrophic temper tantrums if reminded that he was really a boy. It is, of course, highly unlikely that GID “causes” PDD or the other way round. Rather, it is conceivable that the relation between GID and PDD is linked by traits of behavioral rigidity and obsessionality.

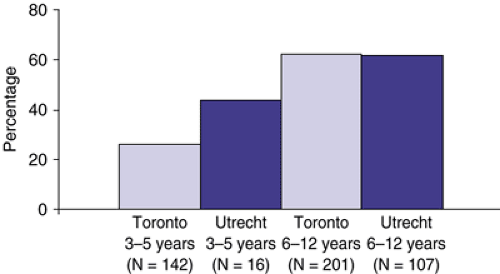

The most systematic information on general behavior problems in children with GID comes from parent-report data using the CBCL. On the CBCL, clinic-referred boys and girls with GID show, on average, significantly more general behavior problems than do their siblings and nonreferred children 11,14. Figure 5.13.2 shows the percentage of 3–5- and 6–12-year-olds from the Toronto and Dutch clinics of GID children with clinical range scores on the CBCL.

Patterns and Correlates of Behavior Problems

On the CBCL, boys with GID have a predominance of internalizing, as opposed to externalizing, behavioral difficulties, whereas girls with GID do not 11,14. Edelbrock and Achenbach (29) used cluster analysis to develop a taxonomy of profile patterns from CBCL data. Intraclass correlations were calculated and then subjected to centroid cluster analysis, from which profile types were identified and labeled. Intraclass correlations can range from -1.00 to 1.00 and a score of .00 represents the mean of the referred sample in the standardization study.

Using this system, we found evidence for a clear internalizing pattern for boys with GID (14). For 3–5-year-old boys, the mean intraclass correlation for Depressed-Social Withdrawal was .04. For 6–11-year-old boys, the mean intraclass correlations for Schizoid-Social Withdrawal and Schizoid were .04 and .16, respectively. For both age groups, there was considerable “distance” from externalizing profile types; for example, for the 4–5-year-old boys, the mean intraclass correlation for Aggressive-Delinquent was -.42 and for the 6–11-year-old boys, the mean intraclass correlation for Hyperactive was -.33.

Zucker and Bradley (14) found that increasing age was significantly associated with degree of behavior problems in boys with GID (depending on the metric, rs ranged from .28–.42, all ps < .001). This finding was replicated in the cross-national, cross-clinic comparative study by Cohen-Kettenis et al (11).

One explanation for these age effects pertains to the role of peer ostracism. That children with GID experience significant difficulties within the peer group has been noted for some time. Using a composite index of poor peer relations derived from three CBCL items (Cronbach’s alpha = .81), Zucker et al (15) showed that children with GID had significantly more peer relationship difficulties than did their siblings, even when controlling for overall number of behavior problems. Cohen-Kettenis et al (11) found that in both Toronto and The Netherlands boys with GID had significantly poorer peer relations than girls with GID, consistent with normative studies, which show that cross-gender behavior in boys is subject to more negative social pressure than is cross-gender behavior in girls. Nonetheless, Cohen-Kettenis et al found that poor peer relations was the strongest predictor of CBCL behavior problems in both GID boys and girls, accounting for 32% and 24% of the variance, respectively, suggesting that social ostracism within the peer group may well be a potential mediator between cross-gender behavior and behavior problems.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree