Geriatric Psychiatry

For many individuals, the passage from youth to old age is mirrored by a shift from the pursuit of wealth to the maintenance of health. In late adulthood, the aging body increasingly becomes a central concern, replacing the midlife preoccupations with career and relationships. This is so because of normal diminution in function, altered physical appearance, and the increased incidence of physical illness. Despite these occurrences, the body in late adulthood can still be a source of considerable pleasure and can convey a sense of competence, particularly if attention is paid to regular exercise, healthy diet, adequate rest, and preventive maintenance medical care. The normal state in the aged is physical and mental health, not illness and debilitation. The developmental tasks of late adulthood that lead to mental health are listed in Table 33-1.

Table 33-1

Table 33-1

Developmental Tasks of Late Adulthood

Old age, or late adulthood, usually refers to the stage of the life cycle that begins at age 65. Gerontologists—those who study the aging process—divide older adults into two groups: young-old, ages 65 to 74; and old-old, ages 75 and beyond. Some use the term oldest old to refer to those over 85. Older adults can also be described as well-old (persons who are healthy) and sick-old (persons who have an infirmity that interferes with functioning and requires medical or psychiatric attention). The health needs of older adults have grown enormously as the population ages, and geriatric physicians and psychiatrists play major roles in treating this population.

DEMOGRAPHICS

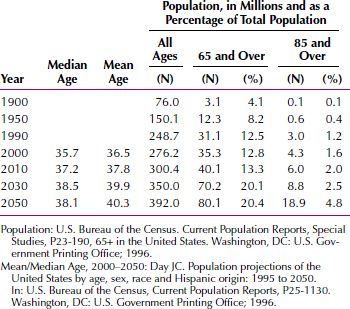

The number of individuals over age 65 is rapidly expanding. In 1900, for example, 4 percent of the US population was older than 65 years. By 2012 it was 13.7 percent, and by 2050, it is projected to be about 20 percent. That increase far exceeds the general population growth—tenfold compared with just over threefold between 1900 and 2000—and is projected to continue (e.g., 2.5 times vs. just over 1.5 times between 1990 and 2050) (Table 33-2).

Table 33-2

Table 33-2

Aging Population of the United States: 1900–2050

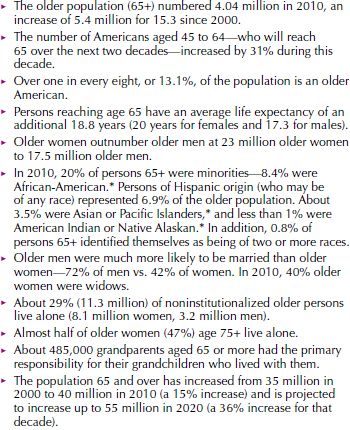

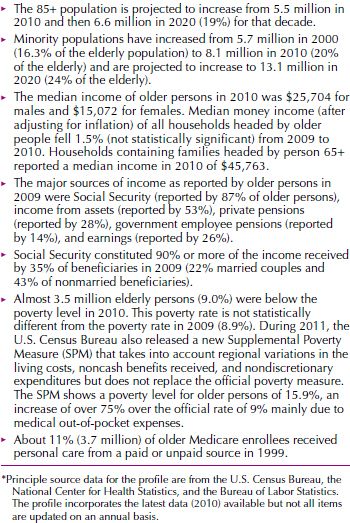

The life expectancy for women at birth is projected to continue to exceed that for men by 7 years until 2050. By 2050, the composition of the US population by age and sex is estimated to differ markedly from that today. Such changes are bound to influence income and marital statistics, the percentage of elderly persons living alone or in long-term care facilities, and other aspects of the social network. A summary of demographic highlights of the aged is given in Table 33-3.

Table 33-3

Table 33-3

Demographic Highlights of the Aged

The accuracy of these projections, however, depends on the accuracy of other predications such as birth rates, immigration, and emigration—all of which are more difficult to gauge for the future than the remaining variables, death rates, or life expectancies. Projections concerning life expectancy, for example, can change substantially within a single decade.

BIOLOGY OF AGING

The aging process, or senescence (from the Latin senescere, “to grow old”), is characterized by a gradual decline in the functioning of all of the body’s systems—cardiovascular, respiratory, genitourinary, endocrine, and immune, among others. But the belief that old age is invariably associated with profound intellectual and physical infirmity is a myth. Many older persons retain their cognitive abilities and physical capacities to a remarkable degree.

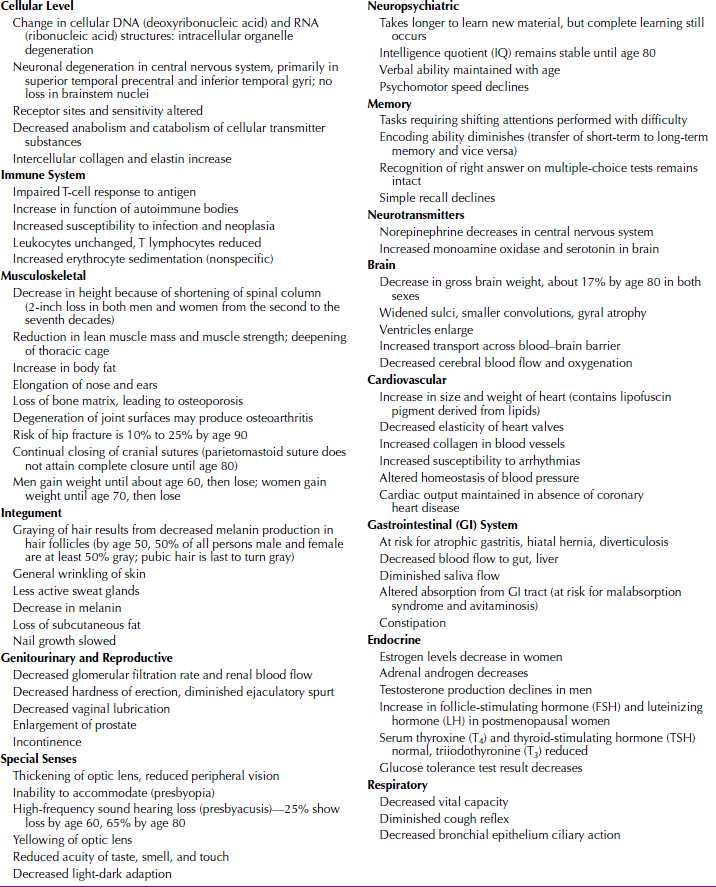

An overview of the biological changes that accompany old age is given in Table 33-4. The various decrements listed do not occur in a linear fashion in all systems. Not all organ systems deteriorate at the same rate, nor do they follow a similar pattern of decline for all persons. Each person is genetically endowed with one or more vulnerable systems, or a system may become vulnerable because of environmental stressors or intentional misuse, such as excessive ultraviolet exposure, smoking, or alcohol use. Moreover, not all organ systems deteriorate at the same time. Any one of a number of organ systems begins to deteriorate, and this deterioration then leads to illness or death.

Table 33-4

Table 33-4

Biological Changes Associated with Aging

Aging generally means the aging of cells. In the most commonly held theory, each cell has a genetically determined life span during which it can replicate itself a limited number of times before it dies. Structural changes occur in cells with age. In the central nervous system, for example, age-related cell changes occur in neurons, which show signs of degeneration. In senility (characterized by severe memory loss and a loss of intellectual functioning), signs of degeneration are much more severe. An example is the neurofibrillary degeneration seen most commonly in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.

Structural changes and mutations in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) are also found in aging cells; these have been attributed to genotypic programming, X-rays, chemicals, and food products, among others. Probably no single cause of aging exists, and all areas of the body are affected to some degree. Genetic factors have been implicated in disorders that commonly occur in older persons, such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, arteriosclerosis, and neoplastic disease. Family studies indicate inheritance factors for breast and stomach cancer, colon polyps, and certain mental disorders of old age. Huntington’s disease shows an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with complete penetrance. The average age of onset is between 35 and 40 years, but cases have occurred as late as 70 years.

Longevity

Longevity has been studied since the beginning of recorded history and has always been a topic of great interest. The research about longevity reveals that a family history of longevity is the best indicator of a long life; of persons who live past 80, half of their fathers also lived past 80. Nevertheless, many conditions leading to a shortened life can be prevented, ameliorated, or delayed with effective intervention. Heredity is but one factor—one beyond a person’s control. Predictors of longevity that are within a person’s control include regular medical checkups, minimal or no caffeine or alcohol consumption, work gratification, and a perceived sense of the self as being socially useful in an altruistic role, such as spouse, teacher, mentor, parent, or grandparent. Healthy eating and adequate exercise are also associated with health and longevity.

Life Expectancy

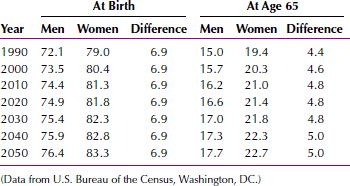

In the United States, the average life expectancy of both sexes has increased in every decade—from 48 years in 1900 to 77.4 years for men and 82.2 years for women in 2013. The projected life expectancy at birth and at age 65 is indicated in Table 33-5. Changes in morbidity and mortality have also occurred. Over the past 30 years, for example, a 60 percent decline has occurred in mortality from cerebrovascular disease and a 30 percent decline in mortality from coronary artery disease. In contrast, mortality from cancer, which rises steeply with age, has increased, especially cancer of the lung, colon, stomach, skin, and prostate.

Table 33-5

Table 33-5

Projected Life Expectancy at Birth and Age 65, by Sex: 1990–2050 (in Years)

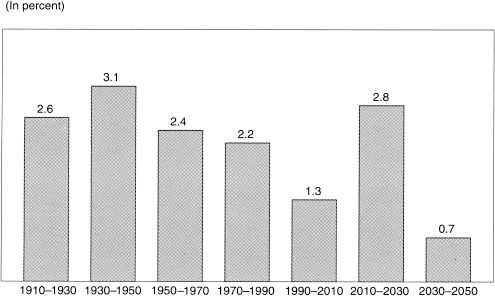

The oldest old, persons over 85 years of age, is the most rapidly growing segment of the older population. Over the past 25 years, the population of all older persons increased by 100 percent, compared with 45 percent for the entire US population, but the increase for the 85 and older group exceeded 275 percent. It is expected that by 2050, the oldest old will make up about 25 percent of the elderly population and 5 percent of the total population in the United States. Figure 33-1 gives projected percentages for the average annual growth rate of the elderly population to 2050.

FIGURE 33-1Average annual growth rate of the elderly population. (Data from U.S. Bureau of the Census.)

The leading causes of death among older persons are heart disease, cancer, and stroke. Accidents are among the leading causes of death of persons over 65. Most fatal accidents are caused by falls, pedestrian incidents, and burns. Falls are most commonly the result of cardiac arrhythmias and hypotensive episodes.

Some gerontologists consider death in very old persons (over 85) to result from an aging syndrome characterized by diminished elastic-mechanical properties of the heart, arteries, lungs, and other organs. Death results from trivial tissue injuries that would not be fatal to a younger person; accordingly, senescence is viewed as the cause of death.

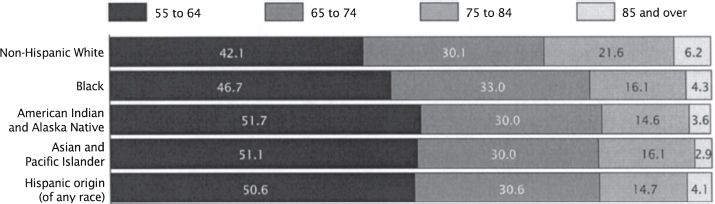

Ethnicity and Race

The proportion of older persons in the black, Hispanic, and Asian populations is smaller than that in the white population, but it is increasing rapidly. By 2050, 20 percent of older persons will be nonwhite. The proportion of older persons who are Hispanic will increase from 4 percent to approximately 14 percent over the same period. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Hispanic refers to persons “whose origins are Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American, and other Hispanic or Latino, regardless of race” (Fig. 33-2).

FIGURE 33-2Percent distribution of people 55 years and over by race, Hispanic origin, and age: 2002. (Data from U.S. Bureau of the Census.)

Sex Ratios

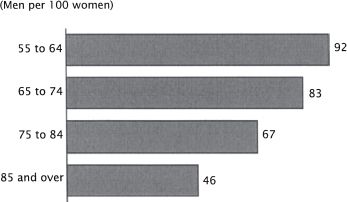

On average, women live longer than men and are more likely than men to live alone. The number of men per 100 women decreases sharply from age 65 to 85 (Fig. 33-3).

FIGURE 33-3Sex ratio of people 55 years and over by age: 2002. (Data from U.S. Bureau of the Census.)

Geographic Distribution

The most populous states have the largest number of older persons. California has the most (3.3 million), followed by New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, Michigan, Illinois, Florida, and Ohio, each with more than 1 million. States with high proportions of older persons include Pennsylvania, Florida, Nebraska, and North Dakota. The high proportion in Florida is owing to those who move into the state for retirement; in the others, because of young persons moving out.

Exercise, Diet, and Health

Diet and exercise play a role in preventing or ameliorating chronic diseases of older persons, such as arteriosclerosis and hypertension. Hyperlipidemia, which correlates with coronary artery disease, can be controlled by reducing body weight, decreasing the intake of saturated fat, and limiting the intake of cholesterol. Increasing the daily intake of dietary fiber can also help decrease serum lipoprotein levels. A daily intake of 1 ounce (about 30 mL) of alcohol has been correlated with longevity and elevated high-density lipoproteins (HDL). Studies have also clearly demonstrated that statin drugs that reduce cholesterol have a dramatic effect on reducing cardiovascular disease in persons with diet-resistant or exercise-resistant hyperlipidemia.

Low salt intake (less than 3 g a day) is associated with a lowered risk of hypertension. Hypertensive geriatric patients can often correct their condition by moderate exercise and decreased salt intake without the addition of drugs.

A regimen of daily moderate exercise (walking for 30 minutes a day) has been associated with a reduction in cardiovascular disease, decreased incidence of osteoporosis, improved respiratory function, the maintenance of ideal weight, and a general sense of well-being. Exercise has been shown to improve strength and function even among the very old. In many cases, a disease process has been reversed and even cured by diet and exercise, without additional medical or surgical intervention.

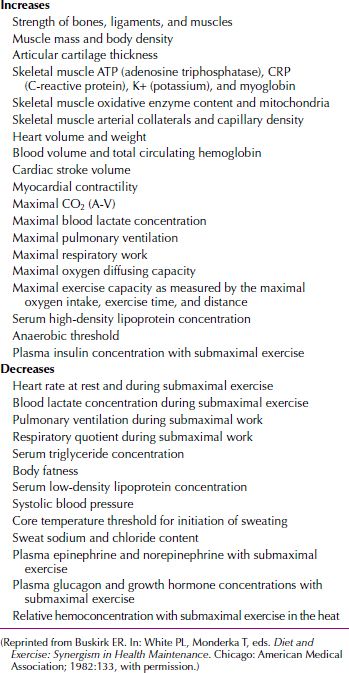

Table 33-6 lists the biological changes associated with diet and exercise. A comparison with Table 33-2 reveals that almost every biological change associated with aging is positively affected by diet and exercise.

Table 33-6

Table 33-6

Positive and Healthy Physiological Effects of Exercise and Nutrition

STAGE THEORIES OF PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT

Early personality theorists proposed that development was completed by the end of childhood or adolescence. One of the first development theorists to propose that personality continues to develop and grow over the life span was Erik Erikson. Erikson believed that development proceeded through a series of psychosocial stages, each with its own conflict that is resolved by the individual with greater or lesser success. Erikson termed the crisis of the last epoch of life integrity versus despair and believed that successful resolution of this crisis involved a process of life review and achieving a sense of peace and wisdom through coming to terms with how one’s life was lived. For example, Erikson proposed that successful resolution of this crisis would be characterized by a sense of having lived one’s life well, whereas a less successful resolution would be characterized by feeling that life was too short, that one did not choose wisely, and bitterness that one will not have a chance to live life over.

Several studies have attempted to validate aspects of Erikson’s theory. In one study, a sample of more than 400 men was studied prospectively, and the highest Eriksonian life stage each achieved was rated according to data gathered on the circumstances of his life. For example, if a man had achieved independence from his family of origin and was self-sufficient but was unable to develop an intimate relationship, the highest life stage achieved would be the identity stage, not the intimacy stage. This study found that Eriksonian stages are passed through in sequential order, although often not at the same age for every individual, and that the stages are surprisingly universal in populations that are ethnically and socioeconomically diverse.

A longitudinal study of approximately 500 subjects from two age cohorts found that the earlier age cohort scored significantly higher on integrity than the later age cohort, and scores for both age cohorts on integrity had declined significantly by the final time of testing. These data suggest that the conflict of integrity versus despair may have a more favorable outcome in earlier age cohorts than in later ones, raising the possibility that changing societal values have had a negative impact on the struggle for integrity. Another study found that wisdom, a construct related to integrity, bore a stronger relation to life satisfaction in elderly adults than other variables, including finances, health, and living situation.

A survey of theories of development in old age is given in Table 33-7.

Table 33-7

Table 33-7

Old Age Developmental Theorists

Personality Over the Life Span: Stability or Change?

Although Erikson and other stage theorists focused on unique developmental tasks and stages central to each phase of life, other theorists focused on defining core personality traits within the individual and determining their course over the life span. For example, do those who are gregarious or extroverted during early childhood and adolescence remain extroverted through midlife and old age? Several well-designed longitudinal studies that have followed individuals over periods ranging from 10 to 50 years have found strong evidence for stability in five basic personality traits: extroversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, openness to experience, and conscientiousness. Some studies found slight decreases in extroversion and slight increases in agreeableness as individuals move into the oldest-old category, which contrasts with early theories that proposed that personality rigidifies as individuals age.

Is the fact that personality appears to have considerable stability over time inconsistent with the basic tenets of stage theories? Perhaps not. It may be that although individuals are consistent over time in their basic personality structure, the themes and conflicts with which they struggle change considerably over the life span, from concerns about developing identity and a stable sense of self, to finding a life partner, to issues related to life review, as hypothesized by the stage theories. In addition, in developing theories about personality change, few studies have examined the impact of significant historical events on personality; thus, the ways in which these events may result in personality change have not been studied systematically.

PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF AGING

Social Activity

Healthy older persons usually maintain a level of social activity that is only slightly changed from that of earlier years. For many, old age is a period of continued intellectual, emotional, and psychological growth. In some cases, however, physical illness or the death of friends and relatives may preclude continued social interaction. Moreover, as persons experience an increased sense of isolation, they may become vulnerable to depression. Growing evidence indicates that maintaining social activities is valuable for physical and emotional well-being. Contact with younger persons is also important. Old persons can pass on cultural values and provide care services to the younger generation and thereby maintain a sense of usefulness that contributes to self-esteem.

Ageism

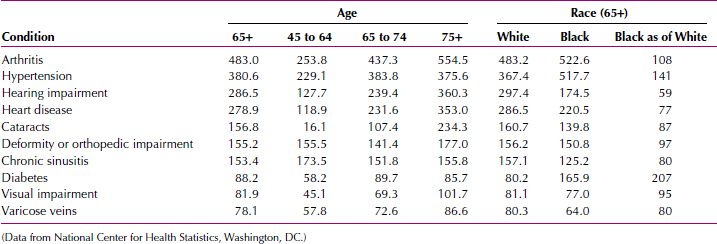

Ageism, a term coined by Robert Butler, refers to discrimination toward old persons and to the negative stereotypes about old age that are held by younger adults. Old persons may themselves resent and fear other old persons and discriminate against them. In Butler’s scheme, persons often associate old age with loneliness, poor health, senility, and general weakness or infirmity. The experience of older persons, however, does not consistently support this attitude. For example, although 50 percent of young adults expect poor health to be a problem for those over 65 years old, 75 percent of persons 65 to 74 years of age describe their health as good. Two thirds of persons 75 and older feel the same way. Health problems, when they do exist, more often involve chronic than acute conditions. More than four of five persons over the age of 65 have at least one chronic condition (Table 33-8).

Table 33-8

Table 33-8

Top Ten Chronic Conditions for People 65+, by Age and Race (Number Per 1,000 People)

Good health, however, is not the sole determinant of a good quality of life in old age. Surveys of old persons show that social contacts are at least as highly valued. In fact, the factors affecting good aging appear to be multidimensional. Aging “robustly” means considering aging in terms of productive involvement, affective status, functional status, and cognitive status. These four indicators are only minimally correlated. The most robustly aging individuals report greater social contact, better health and vision, and fewer significant life events in the past 3 years than their less robustly aging counterparts. A linear, age-related decrease occurs in robustness, but it can still be found among the oldest old.

George Vaillant followed up a group of Harvard freshmen into old age and found the following about emotional health at age 65: Having been close to brothers and sisters during college correlated with emotional well-being; undergoing early traumatic life experiences, such as the death of a parent or parental divorce, did not correlate with poor adaptation in old age; being depressed at some point between ages 21 and 50 predicted emotional problems at age 65; and possessing the personality traits of pragmatism and dependability as a young adult was associated with a sense of well-being at age 65.

Transference

Several forms of transference, some of them unique to adulthood, are present in older adults. First is the well-recognized parental transference, in which the patient reacts to the therapist as a child to a parent. Peer or sibling transference, expressions of experiences from a variety of nonparental relationships, is also common. In this form of transference, the patient looks to the therapist to share experiences with siblings, spouses, friends, and associates. At first, therapists may be surprised by older patients’ ability to ignore their age in creating such transferences.

In son or daughter transference, quite common in middle-aged individuals and the elderly, the therapist is cast in the role of the patient’s child, grandchild, or son-in-law or daughter-in-law. The themes expressed in this form of transference are multiple and often center on defenses against dependency feelings, activity and dominance versus passivity and submission, and attempts to rework unsatisfying aspects of relationships with children before time runs out. Finally, sexual transferences in older individuals are frequent and intense, and the therapist needs to be able to accept them and manage his or her countertransference responses.

Countertransference

Older individuals are dealing with illness and signs of aging, the loss of spouses and friends, and the constant awareness of time limitation and the nearness of death. These are painful issues that are just beginning to come into focus for younger therapists who would prefer not to confront them with great intensity on a daily basis.

A second source of countertransference responses centers on the older patient’s sexuality. The presence of a vivid fantasy life, masturbation, and intercourse are disconcerting in and of themselves if the therapist has not had much experience in working with individuals who are the same age as their parents and grandparents. Consider the experience presented in the case study of a 31-year-old female therapist who was treating a 62-year-old man.

Early in the treatment process, Mr. E’s sexual feelings emerged. His well-groomed appearance and adolescent-like nervousness caused the therapist discomfort. Her concern was how to engender respect and develop a therapeutic alliance with a patient who approached each session as a date, particularly because he was old enough to be her grandfather. At first shocked by his open expression of sexual interest in her, with the help of supervision and her own therapy, she was able to recognize that she and the patient had similar conflicts to resolve, despite the 30-year age difference between them. She had hoped that Mr. E would be “all grown up,” devoid of issues that she was grappling with also. She came to recognize that failure to help him understand the relation between his past and still vibrant sexuality would do the patient a great disservice and would spring from her a lack of understanding of late-life sexual development and her countertransference reaction to him based on her conflicted attitudes toward the sexuality of her parents and grandparents. (Courtesy of Calvin A. Colarusso, M.D.)

Socioeconomics

The economics of old age is of paramount importance to older persons themselves and to society at large. The past 30 years have seen a dramatic decline in the proportion of the US elderly population who are poor, primarily as a result of the availability of Medicare, Social Security, and private pensions. In 1959, 35.2 percent of persons over 65 lived below the poverty line, but by 2012 this figure had declined to 9.1 percent. Persons over age 65 make up 12 percent of the population, but they include only 9 percent of those living at low socioeconomic levels. Women are more likely than men to be poor. Income sources vary for persons age 65 and older. Despite overall economic gains, many older persons are so preoccupied by money worries that their enjoyment of life is lessened. Obtaining proper medical care may be especially difficult when personal funds are not available or are insufficient.

Medicare (Title 18) provides both hospital and medical insurance for those over age 65. About 150 million medical bills are reimbursed under the Medicare program each year; but only about 40 percent of all medical expenses incurred by older persons are covered under Medicare. The rest is paid by private insurance, state insurance, or personal funds. Some services—such as outpatient psychiatric treatment, skilled nursing care, physical rehabilitation, and preventive physical examinations—are covered minimally or not at all.

In addition to Medicare, the Social Security program pays benefits to persons over age 65 (over age 67 in 2027) and pays benefits at reduced rates from age 62 on. To qualify for benefits, a person must have worked long enough to become insured: A worker must have worked for 10 years to be eligible for benefits. Benefits are also paid to widows, widowers, and dependent children if those receiving benefits or contributing to Social Security die (survivor benefits). Social Security is not a pension scheme but a pay-as-you-go income supplement to prevent mass destitution among older persons. Benefits are paid by those currently working to those who are retired. Serious difficulties for Social Security are forecast for the next three decades, when the number of baby boomers reaching old age will greatly exceed the number of younger workers paying into the plan.

Retirement

For many older persons, retirement is a time for the pursuit of leisure and for freedom from the responsibility of previous working commitments. For others, it is a time of stress, especially when retirement results in economic problems or a loss of self-esteem. Ideally, employment after age 65 should be a matter of choice. With the passage of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 and its amendments, forced retirement at age 70 has been virtually eliminated in the private sector, and it is not legal in federal employment.

Most of those who retire voluntarily reenter the workforce within 2 years, for a variety of reasons, including negative reactions to being retired, feelings of being unproductive, economic hardship, and loneliness. The amount of time spent in retirement has increased as the life span has nearly doubled since 1900. Currently, the number of years spent in retirement is almost equal to the number of years spent working.

Sexual Activity

The frequency of orgasm, from coitus or masturbation, decreases with age in men and women. The most important factors in determining the level of sexual activity with age are the health and survival of the spouse, one’s own health, and the level of past sexual activity. Although some degree of declining sexual interest and function is inevitable with age, social and cultural factors appear to be more responsible for the sexual changes observed than for the psychological changes of aging per se. Although satisfying sexual activity is possible for the reasonably healthy elderly, many do not actualize this potential. The widely held notion that the elderly are essentially asexual is often a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree