Geriatric Psychiatry— Dementias

Andreea L. Seritan MD

Michael K. McCloud MD, FACP

Ladson Hinton MD

A 70-year-old man of Middle Eastern descent with limited English skills presents to the geriatric clinic complaining of memory loss for the past 3 months. He has become easily distracted, forgets important dates and recent events, and was in a minor car accident 2 weeks ago. He is brought in by his daughter who readily gives the history, rushes to answer the interviewer’s questions before the patient, and translates the MMSE while at the same time giving clues as to the correct answers.

CLINICAL HIGHLIGHTS

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a useful screening tool for most dementias, but it does not adequately screen for executive dysfunction. Despite a 30/30 score, some patients may still have a dementia syndrome.

Prior to making a diagnosis of dementia, reversible causes of cognitive dysfunction including medical, medication-induced, and psychiatric conditions should be assessed and treated.

Anticholinergic agents and benzodiazepines are generally contraindicated in patients with dementia as they can worsen cognition and cause delirium.

Although there is no cure for neurodegenerative dementias such as Alzheimer disease, medication treatment is the contemporary standard of care and may delay further cognitive and functional decline.

Addressing caregiver burden is an essential part of dementia treatment.

Neuropsychological testing is helpful in distinguishing the dementia syndrome of depression (DSD), formerly known as pseudodementia, from other cognitive deficits.

Clinical Significance

By 2030, one in three U.S. residents will be age 55 or older, and one in five will be at least age 65. Nearly 20% of those aged 55 or older will have psychiatric disorders, including dementias (1). Dementia prevalence increases with age, from 5% of those aged 71 to 79 to 37.4% of those aged 90 and older (2). Given limited access and availability of subspecialty mental health services, elderly patients with dementia and other psychiatric disorders are most often cared for by their primary care clinicians.

Diagnosis

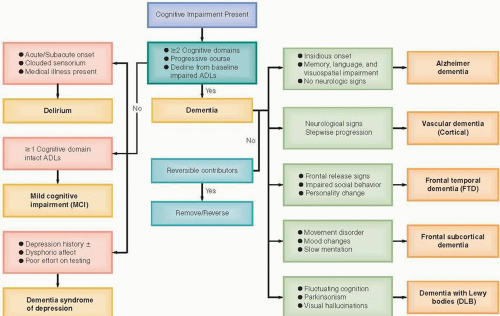

Early diagnosis and treatment of dementias are imperative, as they help to slow cognitive and functional decline. Persons with early-stage dementia are more likely to be able to participate in clinical decision making. Delays in detection of behavior problems result in reactive as opposed to proactive management of dementia and increase reliance on pharmacologic rather than behavioral approaches (3). A simplified algorithm for dementia diagnosis is presented in Figure 12.1.

ESTABLISH PRESENCE OF A DEMENTIA SYNDROME

Dementia implies an acquired, persistent, and progressive impairment in multiple cognitive domains leading to significant functional decline. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) diagnostic criteria require involvement of at least two cognitive domains, one of which is memory (5). Other domains noted are mostly cortical functions (also known as “A” functions):

amnesia (memory recall deficit), aphasia (language impairment), apraxia (inability to perform learned motor sequences in the absence of motor impairment), and agnosia (inability to recognize an object in the absence of sensory impairment) (5). A dementing illness is distinguished from congenital mental retardation syndromes by the criterion of acquired impairment.

amnesia (memory recall deficit), aphasia (language impairment), apraxia (inability to perform learned motor sequences in the absence of motor impairment), and agnosia (inability to recognize an object in the absence of sensory impairment) (5). A dementing illness is distinguished from congenital mental retardation syndromes by the criterion of acquired impairment.

Although impairments of executive function are common in dementias that involve the frontal cortex or subcortical white matter, they are often overlooked. The MMSE does not adequately screen for executive dysfunction. Some patients with subcortical dementias may still have a 30/30 score. Executive function may be assessed by asking questions about the patient’s ability to shop, plan meals, balance the checkbook, keep track of appointments, develop a schedule in advance of an anticipated events, and prioritize things by importance. Collateral information is often crucial. If suspicion exists based on history, several simple tests can be quickly performed in the office to establish whether executive dysfunction is present (Table 12.1) (4).

By contrast, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is defined by deficits in at least one cognitive domain with relatively intact ADLs. In a primary care sample, MCI prevalence was up to 25% in individuals over age 75 (6). MCI is further classified as amnestic (with memory impairment) and nonamnestic, in which other cognitive domains (other than memory) are impaired. Patients with amnestic MCI should be closely followed as they may convert to Alzheimer disease (AD) at a rate of about 15% per year (7). Recent research suggests that neuropsychiatric symptoms, especially depression and apathy, are a predictor of progression to AD (8).

DEMENTIA

Impairment in two or more cognitive domains

Progression of deficits

Functional impairment (difficulty in performing activities of daily living [ADLs])

CORTICAL VERSUS SUBCORTICAL DEMENTIAS

After the presence of a dementia syndrome has been established, it is important to further clarify the diagnosis. If either major focal neurologic deficits or a history of cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) is present together with a sudden onset or a stepwise progressive decline in cognitive function, vascular dementia (VaD) secondary to cortical infarction is most likely present. Pure vascular dementias constitute only up to 10% of all dementias, and many persons who have an onset typical of vascular dementia may later present with more gradual deterioration indicative of AD, thus a mixed AD–VaD dementia (4).

MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

Deficits in one or more cognitive domains

Intact ADLs

Score ≥1.5 standard deviations below average level of age peers on a standardized memory test

In other patients, motor slowing (bradykinesia), ataxia, cogwheel rigidity, shuffled gait, tremor, or chorea may be observed. These movement disorders, along with cognitive slowing (bradyphrenia), apathy, retrieval memory deficit but preserved recall initially, and mood disturbances are typical of neurodegenerative or vascular processes involving subcortical structures (4). Neuronal circuits connect the basal ganglia and other subcortical structures with corresponding areas in the frontal lobes. The dementias associated with impairments of these circuits are called frontal-subcortical dementias. Examples are Huntington disease (HD), Parkinson disease (PD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP),

multiple system atrophy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) dementia, and subcortical CVAs (Table 12.2) (4).

multiple system atrophy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) dementia, and subcortical CVAs (Table 12.2) (4).

VASCULAR DEMENTIA

Neurologic deficits (clinical, neuroimaging)

Stepwise progression

Usually presents with a long-standing history of hypertension

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), a mixed cortical-subcortical dementia, is the third most frequent cause of dementia, after AD and vascular dementia, and accounts for 15% to 20% of dementias. Onset of the disease varies between 50 and 90 years of age, and dementia usually occurs within 1 year of the onset of parkinsonism. Exquisite sensitivity to antipsychotic side effects and repeated falls are supportive diagnostic features. Delusions, delusional misidentification, mood changes, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder are other prominent neuropsychiatric manifestations (9).

FRONTAL-SUBCORTICAL DEMENTIA

Movement disorders

Mood disturbance

Psychomotor and cognitive slowing (apathy)

OVERVIEW ON CORTICAL DEMENTIA AND ALZHEIMER DISEASE

Pure AD constitutes about 35% of all dementias, while mixed AD–VaD accounts for 15% (4). AD is the quintessential amnestic dementia and often presents with anterograde memory loss (difficulty learning new information). Onset is insidious, with early word-finding difficulties progressing slowly to empty but fluent speech, accompanied later by visuospatial impairment. Poor insight into cognitive deficits is typical, while poor judgment and planning may follow as the illness progresses to involve the frontal lobes. Wandering and unsafe driving are other cardinal manifestations.

DEMENTIA WITH LEWY BODIES

Fluctuating mental status

Parkinsonism

Visual hallucinations

Poor response to antipsychotics

The MMSE is particularly useful in screening for cortical dementias, especially AD, since it is heavily weighted toward language and memory. Most practitioners use a cut-off score of 24 in screening; however, higher thresholds need to be used in highly educated patients. Difficulty

with recall (especially if not helped by cues), naming, temporal orientation, and polygon copying are typically found in AD. The clock drawing test examines multiple cognitive domains, including visuospatial skills (Table 12.1) (4).

with recall (especially if not helped by cues), naming, temporal orientation, and polygon copying are typically found in AD. The clock drawing test examines multiple cognitive domains, including visuospatial skills (Table 12.1) (4).

ALZHEIMER DISEASE

Memory loss (early word-finding difficulties, anterograde amnesia)

Language impairment

Visuospatial skills impairment

In addition to VaD with cortical strokes and AD, the other major cortical dementia class is frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), which accounts for 5% of dementias (4). FTLD is a heterogenous term that includes frontotemporal dementia (FTD or Pick disease), FTD with motor neuron disease (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), progressive nonfluent aphasia, semantic dementia, and progressive apraxia. FTLD usually develops between ages 45 and 65, whereas AD usually presents after age 65 (4). The FTD clinical picture is one of profound alteration in social conduct and personality. Memory failures result from executive, organizational, and retrieval deficits rather than from amnesia.

FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA

Disinhibition (personality change)

Early loss of social awareness

Early loss of insight

Hyperorality

Stereotyped and perseverative behavior (wandering, mannerisms)

REVERSIBLE CONTRIBUTORS

Completely reversible dementias are rare, although reversible comorbid conditions are common in dementia. Identifying reversible etiologies of cognitive deficits is important, although in some cases (alcohol, vitamin B12 or folate deficiency) neuropsychiatric sequelae can only be partially reversed. Replacement of vitamin B12 levels below 350 pmol/L is recommended because checking for elevated homocysteine or methylmalonic acid levels may be more expensive and serial blood tests are often necessary. Table 12.3 lists suggested studies for dementia work-up (10). Computerized tomography (CT) will screen for most intracranial mass lesions, hematomas, hydrocephalus, and strokes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended when white matter disease is suspected, such as with subcortical strokes or multiple sclerosis. Periventricular white matter disease consistent with small vessel ischemia is a commonly reported finding and it does not rule out AD. Functional imaging studies, such as positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), may indicate impairment before structural changes are visible. Medicare covers PET when used to differentiate AD from FTLD (5). Neuropsychological testing is helpful in distinguishing the dementia syndrome of depression, formerly known as pseudodementia, from other cognitive deficits.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree