13 Atul Goel and Trimurti D. Nadkarni Cavernous angioma of the cavernous sinus is an uncommon lesion accounting for ~2% of all cavernous sinus tumors.1–5 This benign tumor is a neurosurgical challenge because of the high vascularity, location within the cavernous sinus, and relationship to the intracavernous internal carotid artery and cranial nerves. Cavernous angiomas of the cavernous sinus are vascular malformative lesions, analogous to the intraaxial cavernous angioma. Some authors feel that the correct term for extracerebral cavernous (hem)angiomas is cavernoma, or venous vascular malformation of the cavernous type.6 The term hemangioma should be avoided and reserved for the vascular tumors commonly seen in infants.6 Cavernous angiomas in the cavernous sinus are anatomically and physically different from cavernomas or cavernous angiomas of the cerebral parenchyma. Histologically, cavernous angioma involving the cavernous sinus is similar to intracerebral cavernous angioma but is a distinct clinical entity, and the management issues are vastly different from those located within the cerebral parenchyma and other extracerebral locations. Histology reveals that cavernous angiomas of cavernous sinus are vascular malformations composed of large vascular channels lined by flat endothelium and separated by fibroconnective tissue stroma. Ohata et al. have described the cavernous angioma to be a cluster of sinusoidal cavities, the size of which depends on the systemic blood pressure.7 Katada et al. suggest that growth mechanism of cavernous angioma could be progressive ectasia of vessels or their autonomous development at the edges of the lesions.8 Cavernous angiomas involving the dural confines of the cavernous sinus frequently reach giant size before diagnosis. Radiation treatment has been successful.9–11 However, the general consensus favors radical surgery as the primary and the only modality of therapy for these benign tumors. Understanding of the anatomic location and relationships and the vascular pattern of the tumor can lead to a successful resection even through a small exposure. As the surgical principles involved in the treatment are different from all other brain lesions, an experience in the surgical resection of these tumors is of great help during surgery. Fifteen patients with cavernous angiomas of the cavernous sinus, 10 females and 5 males aged from 15 to 55 years (mean, 30 years), were treated in our unit from 1992 to 2003. The duration of symptoms at the time of presentation ranged from 7 days to 2 years (mean, 40 days). All patients were treated with radical surgery and followed up from 8 months to 9 years (mean, 45 months). The principal clinical features are shown in Table 13-1. All patients presented with symptoms of headache. Thirteen patients had sudden onset of single or multiple cranial nerve pareses, and the symptoms were progressive in three of these patients. Four patients had visual deficits on the side of the tumor, one of which had visual deficits on both sides, worse on the side of the tumor. The visual deficits were progressive in all patients. Six patients had moderate to severe pain in the face on the side of the tumor. Two patients had no cranial nerve deficit at presentation; one presented with an episode of generalized convulsions and headache, and the other had only headache.

Giant Cavernous Angiomas of the Cavernous Sinus

Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment at King Edward Memorial Hospital: Clinical Experience

Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment at King Edward Memorial Hospital: Clinical Experience

| Symptoms | No. of Patients | Percent of Patients |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | 15 | 100 |

| Retroorbital and facial pain | 6 | 46.2 |

| Visual impairment | 4 | 30.8 |

| Impaired corneal reflex | 9 | 69.2 |

| Decreased sensation over face | 10 | 76.9 |

| Wasted temporalis/masseter muscle | 8 | 61.5 |

| Sixth cranial nerve paresis | 12 | 80 |

| Third cranial nerve paresis | 11 | 73.3 |

| Seizures | 2 | 15.4 |

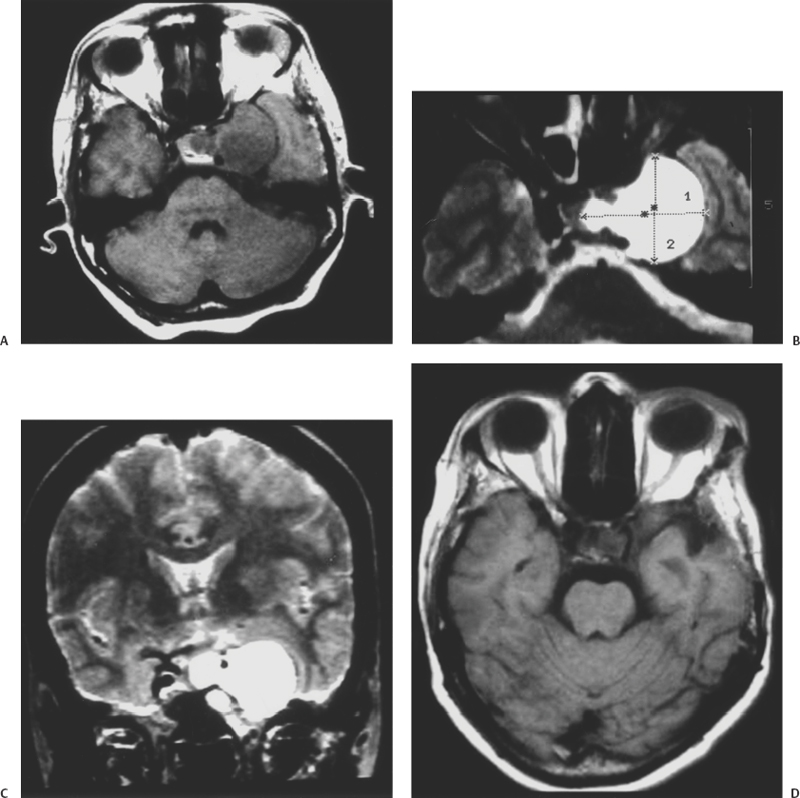

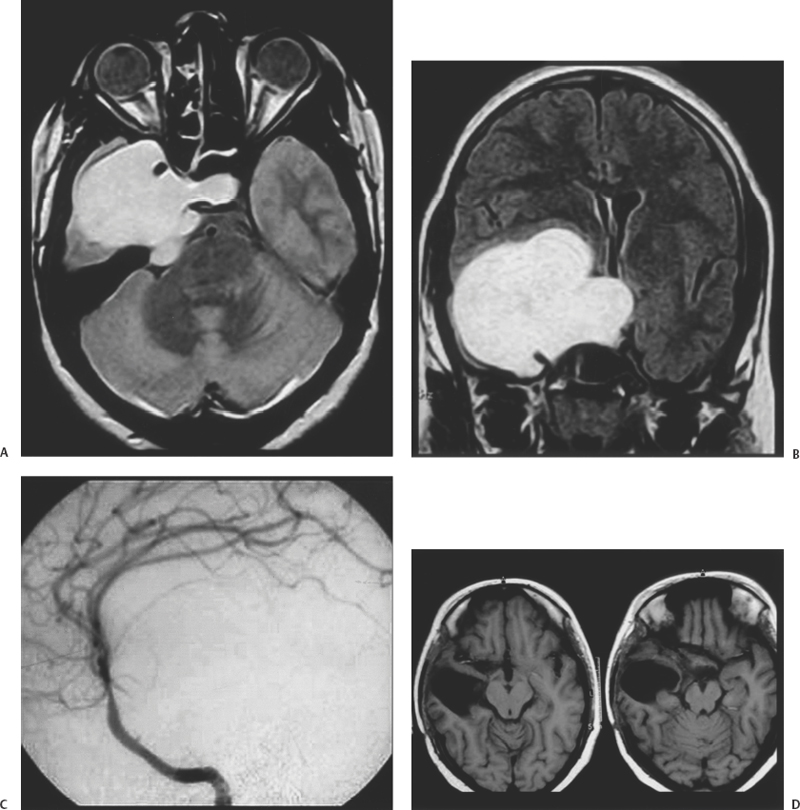

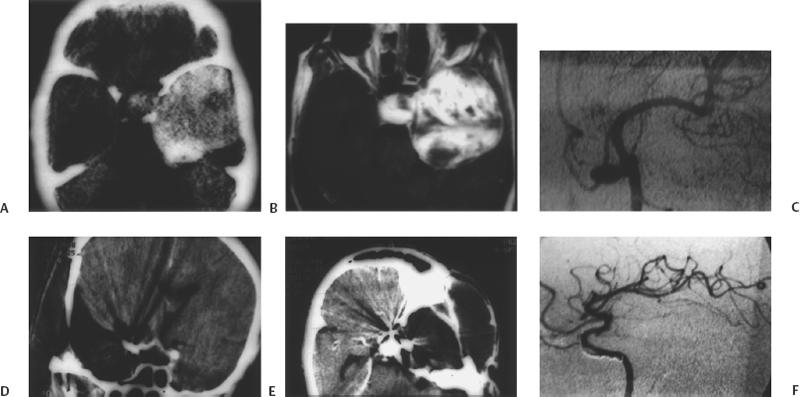

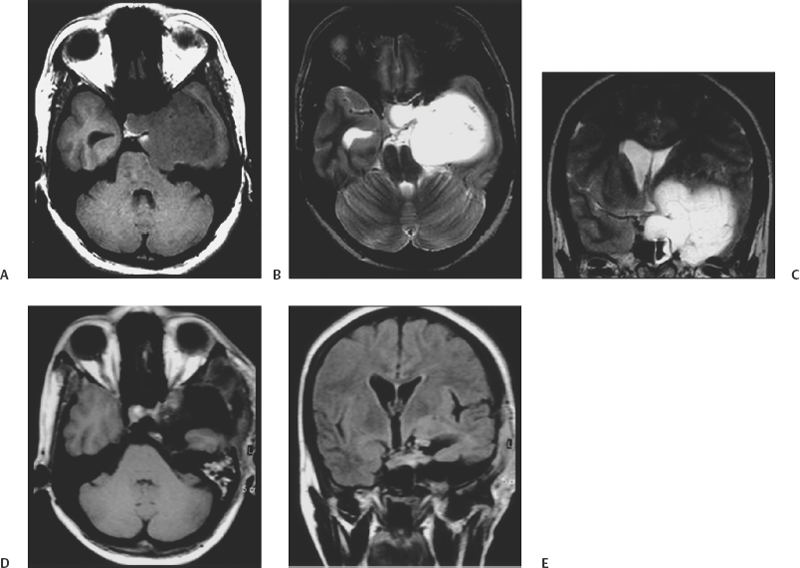

All patients were investigated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). CT showed the lesion as hypodense to isodense with marked enhancement after contrast administration. On T1-weighted MRI, the lesion was moderately hypointense, and on T2-weighted MRI, the lesion was highly hyperintense. The size of the lesion ranged from 28 to 73 mm in maximum dimension (mean, 44 mm). All cavernous angiomas irrespective of size were located entirely within the dural confines of the cavernous sinus and had extensions toward the petrous apex, superior orbital fissure, and the sella (Figs. 13-1 to 13-4). All lesions encased the internal carotid artery circumferentially during its course through the cavernous sinus.

Angiography was performed in five patients. These lesions were angiographically relatively “occult” despite the intense vascularity encountered during surgery (Figs. 13-2 and 13-3). There was a relatively minor vascular blush in all cases. Small leashes of vessels arising from the internal carotid artery fed the cavernous angioma. The cavernous angioma was also fed by larger vessels such as the inferolateral trunk in four cases and from the region of the McConnell capsular artery in two cases. Preoperative embolization was not possible in any of our series as the feeding vessels were too small. One case of huge cavernous angioma incorporated a large aneurysm in the intracavernous segment of the internal carotid artery associated with evidence of intralesional bleeding (Fig. 13-3). There was no evidence of hemorrhage in any other lesion. No case showed any calcification or necrosis.

Figure 13-1 A 40-year-old woman presented with headaches associated with third, sixth, and fifth cranial nerve dysfunction. (A) Axial T1-weighted image showing an isointense left cavernous sinus angioma with a sellar extension. (B) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image showing the hyperintense left cavernous tumor. (C) Coronal T2-weighted image shows the carotid artery to be encased by the tumor. (D) Postoperative T1-weighted axial image demonstrates complete excision of the cavernous sinus mass.

Figure 13-2 A 15-year-old girl presented with diminution of vision in both eyes for 6 months. She had right eye ptosis and diplopia for a fortnight. On examination, she had only perception of light in the right eye and finger counting vision in the left eye at 3 feet. There was total ophthalmoplegia of the right eye. The right fifth nerve demonstrated motor, sensory, and corneal affection. (A) Axial proton density magnetic resonance image demonstrated a large hyperintense right intracavernous sinus tumor. (B) Postcontrast T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showed the tumor to enhance and the carotid artery to be encased. (C) Right internal carotid angiogram demonstrated no tumor blush. (D) Postoperative axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance images showing complete excision of the tumor.

Orbitozygomatic osteotomy, basal pterional craniotomy, and an intradural approach to the lesion were performed in our first case.12 Intraoperative control of the internal carotid artery in the neck was performed in this patient. A basal zygomatic bone-based temporal craniotomy was performed with the patient in a lateral position in all other cases. Proximal control of the internal carotid artery in the neck or in the petrous apex was not obtained in these patients. Lumbar drainage of the cerebrospinal fluid was performed during surgery. Exposure of the lesion extradurally was attempted in the latter 14 cases but was possible only in 11 cases, whereas the extradural approach was adopted but an additional intradural approach was used to facilitate resection and to confirm the completeness of removal in the other three cases. A large part of the lesion lateral to the carotid artery was removed en bloc by careful dissection from the adjoining structures in two cases of relatively small cavernous angiomas. However, the lesion was large and required piecemeal resection in the other cases. Total resection was achieved in 14 patients and partial resection was achieved in one patient.

Figure 13-3 A 50-year-old female presented with acute onset of ophthalmoplegia 5 days prior to admission. (A) Axial computed tomography (CT) with contrast shows a massive cavernous sinus mass that occupies nearly the entire middle cranial fossa. (B) Postcontrast axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing enhancement with extensions into the sella, superior orbital fissure, and the Meckel cave. (C) Left internal carotid angiogram showing a large aneurysm on the anterior ascending segment of the artery. The tumor demonstrates no significant blush. (D) Postoperative coronal (CT) scan shows complete excision of the tumor with clip artifacts. (E) Axial CT demonstrates complete excision of the tumor. (F) Postoperative left carotid artery angiogram shows the aneurysm to be completely excluded from circulation.

Figure 13-4 A 43-year-old woman presented with one episode of generalized seizure but without any neurologic deficit. (A) Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows a hypointense cavernous sinus tumor. (B) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image demonstrates the tumor to be hyperintense. (C) Coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image showing the large dimensions of the tumor. (D) Postoperative axial T1-weighted image and (E) coronal T1-weighted image shows complete excision of the giant cavernous angioma of the cavernous sinus.

The sixth cranial nerve could not be identified in its course within the cavernous sinus in seven patients. The sixth cranial nerve was identified in eight patients and could be completely preserved in five patients. In the immediate postoperative phase, none of the patients showed recovery of function of any cranial nerve. Extraocular movements completely recovered in five patients ~12 months after surgery. One patient who had intact preoperative function of all cranial nerves developed sixth cranial nerve paresis after surgery, but the third cranial nerve remained normal. At follow-up after 18 months, she showed complete recovery of all extraocular movements. Nine patients had moderate to severe dysfunction of the extraocular movements, and both the third and the sixth cranial nerves were affected. Six patients showed partial recovery of third cranial nerve function. All patients were relieved of the headaches after surgery. During the follow-up period, no recurrence or regrowth of the residual cavernous angioma was found, and all patients are leading active lives.

Literature Review of Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment

Literature Review of Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment

Cavernous angiomas of the cavernous sinus are frequently seen in the fourth and fifth decades of life.12,13 Nearly half of the reported cases were of Japanese origin.13 Ninety-four percent of the reported cases occurred in women.2 In our series, 67% were females. Symptoms have been reported to first appear or to worsen with pregnancy.1, 14 Considering that females in their youth or middle age are more common victims of this lesion, the origin may be hormonal.14,15

Clinical presentation is usually in the form of symptoms related to the acute or subacute dysfunction of the nerves traversing the cavernous sinus and the optic nerve. Hemorrhage within the cerebral cavernous angiomas is a common feature but is relatively uncommon in cavernous angiomas located in the cavernous sinus.13,16 Despite the acute nature of clinical presentation in 10 cases, only 1 case had evidence of bleeding.17,18 In the absence of a bleed within the lesion, it appears that the acute cranial nerve symptoms may be a result of an ischemic insult. In our series, one patient had no affection of any cranial nerve and presented with the primary symptom of severe headache. The rest of the patients had deficit involving cranial nerves coursing through the cavernous sinus. Vision was affected in four patients. The cause of the visual affection could be due to a vascular steal phenomenon as in high-flow arteriovenous malformations. Headache, which varied in intensity from moderate to severe, was present in all patients and was the most disabling clinical feature. Two patients had generalized seizures. No other hemisphere-related symptoms occurred in any patient. Pituitary hypofunction has been reported with these lesions2,18 but was not encountered in our series. An acute cavernous sinus syndrome, manifesting as retroorbital pain, blepharoptosis of the eye, diplopia, and sensory disturbance of the face similar to the Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, has been reported.8 Yamamoto et al. have reported amenorrhea and hyperprolactinemia in a 34-year-old female as presenting symptoms.19 Exophthalmos, trigeminal neuralgia, and hemi- or monoparesis are the other reported symptoms at the time of presentation.2

Improvement in the diagnosis after the introduction of computer-based imaging had led to an increased rate of diagnosis of cavernous angiomas in intracerebral and extracerebral locations. Identification of the lesions as cavernous angioma within the cavernous sinus on the basis of preoperative clinical findings and radiologic parameters is crucial for planning of the surgical strategy. Radiographically, cavernous angiomas of the cavernous sinus have a characteristic pattern of extension toward the sella, superior orbital fissure, and the Meckel cave, which was observed in all our cases and in the majority of reported cases with radiography of the lesion.2,3,13 Cavernous angioma is the only primary intracavernous sinus tumor. Irrespective of the size, the tumor has never been found to protrude out of the anatomic dural confines of the cavernous sinus. The extension toward the sella appears to be through the enlarged intercavernous sinus. Extension into the other tributaries of the cavernous sinus such as the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses has not been encountered. Erosion of the bones of the middle fossa floor, sphenoid wing, and the temporal squama and wasting of the temporalis and masseter muscles in some cases suggest the slow growth and progression of these lesions.10

Cavernous angioma is hyperdense on CT with brilliant enhancement after contrast administration. Extraaxial cavernous angiomas differ from intraaxial ones on MRI in that the hemorrhagic variant is less frequent, hemosiderin ring is rare, the signal characteristics are different, and contrast enhancement is the rule.20 The lesion is hypointense on T1-weighted MR images and highly hyperintense on T2-weighted images.21,22 The lesion encased the internal carotid artery during its entire course in the cavernous sinus in all our cases. Cavernous angioma is usually angiographically “occult” despite the extensive vascularity,10,13 although a mild blush is frequently seen.2,13,23–26 This blush has been observed to have flecked, pooling, or lake-like appearance in the late venous phase.2 As in our cases, the inferolateral trunk,15,23,27 meningohypophyseal trunk,10,11,18 accessory meningeal artery,18,26 and middle meningeal artery2,9–11 have been identified as major feeding vessels. In two of our cases, there was a relatively large feeder from the region of the McConnell capsular artery. Preoperative embolization of the lesion has been reported,2,9,12,18 but this could not be done in our series because of the small size of the feeding vessels. An aneurysm of the internal carotid artery was seen in one of our cases.28 Although likely, it is difficult to confirm whether this associated aneurysm was due to high-pressure blood flow in the cavernous angioma simulating the aneurysm seen on feeding vessels of intracranial arteriovenous malformations.

Thallium-201 (201Tl) single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) shows low uptake in cavernous sinus angiomas, and technetium-99m-human serum albumin-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid SPECT reveals high uptake within tumor. 201Tl SPECT usually shows very high uptake in meningiomas and malignant tumors. Thus, SPECT is useful for distinguishing cavernomas from other cavernous sinus tumors.29

Selection of the operative route for cavernous sinus-related lesions, the extent of exposure necessary, the need for operative control of the carotid artery, and feasibility and need of radical resection depend on the histologic nature of the lesion. The age and sex of the patient, principal presenting signs, size of the lesion, extent of cranial nerve and carotid artery involvement, imaging characters, and other such features are helpful in estimating the consistency and vascularity of the lesion, site of origin, and direction of its spread and the extent and nature of cavernous sinus involvement. Evaluation of the histology of the lesion on the basis of radiologic and clinical parameters and the impact on decision regarding the surgical strategy is paramount.30

Surgical excision is the most acceptable therapy for cavernous angiomas of the cavernous sinus considering the benign nature of the lesion and potential curability. 2,10,11,23,26,31–34 Smaller lesions and those with mild symptoms can be clinically and radiologically observed. The main difficulty during surgery for cavernous angioma is the vascularity of the lesion.2,11,27 Surgical resection carries the risk of extensive and uncontrollable bleeding. Surgical misadventures have resulted in high morbidity and mortality.2,14,18 Preoperative radiation treatment as a modality to reduce lesion vascularity has been suggested.2,11,25,35 Direct puncture and injection of sclerosing agents (alcohol, fibrin glue, plastic adhesive material) in the lesion has produced good results.36–38 Induced hypotension and hypothermia may be useful adjuncts for surgery.7

In our first case, we performed an orbitozygomatic osteotomy and basal frontotemporal approach.12 However, we observed that the brain in these cases was lax and the tumor was soft and compressible, so elaborate skull base exposures could be safely avoided. In the later part of our series, we performed a basal temporal craniotomy based over the entire zygomatic bone. The lateral aspect of the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone was removed. Bone work in the extradural space was restricted to prevent avoidable blood loss. We observed that extradural exposure was the most appropriate approach for these essentially intracavernous sinus lesions. The lateral dural wall of the cavernous sinus could be stripped in a relatively bloodless field from the inner dural layer containing the splayed out cranial nerves.39 The incision in the inner layer was taken toward the base to avoid injury to the first division of the fifth cranial nerve. Extradural surgery avoided handling of the temporal brain and reduced the possibility of postoperative seizures.

In our earlier report on this subject,12 we recommended en bloc excision of the cavernous angioma. Other authors have also favored an en bloc tumor excision.2 En bloc resection of these lesions is most suitable for small, moderate, and even large cavernous angiomas. Although, identified by some,2,3 a pseudocapsule providing an opportunity for surgical dissection plane was not observed in our series. Most of the cavernous angiomas were very large or giant in our series, so we preferred an alternative method of dissection. The lesion was first dissected from its surface in an en bloc manner. However, during this dissection whenever the cavernous angioma bleeding was significant and excessive, a debulking of the lesion was performed by working within the mass. The red, extensively vascular lesion was soft and contained thin vascular channels and could be debulked and decompressed using relatively powerful and controlled suction. Avoiding sharp dissection in the cavernous sinus while working in a bloody field was useful to preserve the internal carotid artery and the cranial nerves. We observed that hemostasis was achieved spontaneously after a large part of the lesion was resected, and the residual cavernous angioma could be resected under vision from the corners. The technique of minor resection and then hemostasis before further tumor resection and maintaining a bloodless field may not be applicable in these cases. Such a procedure is associated with greater overall blood loss than if a relatively quick resection is performed. Partial or subtotal resections are not recommended and can lead to difficulty in control of bleeding during surgery and could be associated with an increased incidence of postoperative hemorrhage.

The initial direction of debulking the lesion mass was toward the petrous apex to identify the sixth cranial nerve as the site of its entry into the cavernous sinus. The nerve was then followed distally. The feeding vessels from the intracavernous sinus carotid artery were coagulated as soon as significant debulking was completed and wide exposure of the carotid artery was achieved. The third cranial nerve is located on the dome of the cavernous angioma and is securely placed within the dural walls. The dissection of the lesion in the region of the dome was performed later in the region of the surgery after a large portion of the cavernous angioma had been removed from within the cavernous sinus and the bleeding from the lesion was under control.

Radical resection of cavernous angiomas located within the cavernous sinus is possible by an entirely extradural route. Rapid decompression of the lesion after wide exposure can lead to successful resection. The outcome for extraocular movements is excellent after surgery on small or moderate-size cavernous angiomas. However, the outcome of extraocular movement was poor in our series after surgery in giant cavernous angiomas. Recurrence rates after successful resection are extremely low.13,40 There was no recurrence or re-growth in any of our patients.

Radiotherapy has been demonstrated to show complete disappearance of cavernous sinus angioma or a significant reduction in size of the tumor. There has been symptomatic relief and recovery of cranial nerve function. Radiation has been used in doses of 30 to 40 grays.19,41–45 Radiotherapy should be considered for patients with incomplete tumor excision or for patients who are too ill to undergo surgery.2 Radiosurgery has also shown similar results.46–50 Radiosurgery could be beneficial in the treatment of small cavernous angiomas47 and could be a modality of therapy for smaller residual lesions.

References

11. Mori K, Handa H, Gi H, Mori K. Cavernomas in the middle fossa. Surg Neurol 1980;14:21–31

12. Goel A, Nadkarni TD. Cavernous haemangioma in the cavernous sinus. Br J Neurosurg 1995;9:77–80

14. Finkemeyer H, Kautzky R. Das Kavernom des Sinus cavernosus. Zen-tralbl Neurochir 1968;29:23–30

24. Lu Q. [The neuroimaging of the intracranial hemangiomas.] Chin. J Neurosurg 1987;3:137–140

47. Kida Y, Kobayashi T, Mori Y. Radiosurgery of cavernous hemangiomas in the cavernous sinus. Surg Neurol 2001;56:117–122

< div class='tao-gold-member'>