19 Glucose Management and Nutrition Jennifer A. Frontera Hyperglycemia in critically ill patients, often referred to as stress hyperglycemia, is characterized by increased gluconeogenesis, elevated insulin levels, insulin resistance, and increased IGF-binding protein 1. Elevated catecholamines, cortisol, growth hormone, and glucagon also occur in the context of critical illness, contributing to hyperglycemia. Hyperglycemia has been shown to lead to worse outcomes among various critically ill populations and has the highest adjusted odds ratios for mortality among cardiac and neurologic patients. Acute hyperglycemia is common after neurologic injury. It occurs in 30 to 70% of patients and may be mediated by an acute stress response, hypothalamic injury, or catecholamine surge at the time of neurologic injury. Animal models of brain ischemia suggest that hyperglycemia worsens acidosis, excitotoxicity, and breakdown of the blood-brain barrier with consequent edema or hemorrhagic transformation. Elevated admission glucose and prolonged hyperglycemia have been linked to worse outcomes in patients with ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), and traumatic brain injury (TBI).3,4,6,7,8,9 Prolonged hypoglycemia, which can occur as a complication of glucose management, can also lead to neurologic deterioration. Finding the appropriate glucose range and the best way to maintain normoglycemia in the neurologically critically ill is an active area of research. Does the patient have a history of diabetes? Does the patient have a history of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmotic nonketotic hyperglycemia? Does the patient take oral hypoglycemics or insulin at home? Blood glucose should be monitored hourly until stable and other laboratories checked every 2 to 4 hours depending on the severity and clinical response.

History and Examination

History

Physical Examination

Neurologic Examination

Differential Diagnosis

Life-Threatening Diagnoses Not to Miss

Diagnostic Evaluation

Treatment

Insulin

Feeding

Treatment of DKA and HONK (Table 19.2)

Prognosis

| Recommemdation | Grade |

| All patients who are not expected to be on a full oral diet within 3 days should receive enteral nutrition. | C |

| Hemodynamically stable critically ill patients who have a functioning GI tract should be fed early (<24 h) using an appropriate amount of feed. | C |

| During the acute and initial phase of critical illness, in excess of 20–25 kcal/kg BW/d may be associated with a less favorable outcome. | C |

| During the anabolic recovery phase, the aim is to provide 25–30 kcal/kg BW/d. | C |

| Patients with severe undernutrition should receive enteral nutrition up to 25–30 total kcal/kg BW/d. If these target values are not reached supplementary, parenteral nutrition should be given. | C |

| Supplementary intravenous metoclopramide or erythromycin can be administered to patients with intolerance to enteral feeding (i.e., high gastric residuals). | C |

| Use enteral nutrition in patients who can be fed via the enteral route. | C |

| There is no significant difference in the efficacy of jejunal vs gastric feeding in critically ill patients. | C |

| Avoid additional parenteral nutrition in patients who tolerate enteral nutrition and can be fed approximately to the target values. | A |

| Use supplemental parenteral nutrition in patients who cannot be fed sufficiently via the enteral route. Consider careful parenteral nutrition in patients intolerant to enteral nutrition at a level equal to but not exceeding the nutritional needs of the patient. | C |

| Whole protein formulas are appropriate in most patients because no clinical advantage of peptide-based formulas has been shown. | C |

| Immune-modulating formulas (enriched with arginine, nucleotides, and omega 3 fatty acids) are superior to standard enteral formulas in patients with elective upper GI surgery, mild sepsis (APACHE II<10:48 AM 10/6/201010:48 AM 10/6/201015), trauma, and ARDS. Patients with severe sepsis who do not tolerate more than 700 mL of enteral formula per day should not receive immune-modulating formulas. | A-B |

| Glutamine should be added to standard enteral formula in burn and trauma patients. | A |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory disease syndrome; BW, body weight; GI, gastrointestinal.

* See Chapter 22 for a summary of Grades of ESPEN evidence.

Data from: Kreymann KG, Berger MM, Deutz NE, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral

Nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr 2006;25(2):210–223.

| Treatment | Comment |

| Fluid resuscitation | Volume deficit can be as high as 4–6 L because glucose acts as an osmotic diuretic. Replace with NS starting at 15–20 mL/kg BW/h. |

| Insulin | Begin intravenous infusion of regular insulin at 0.1 U/kg as IV bolus followed by 0.1 U/kg/h IV infusion. Check hourly blood glucose values and titrate as necessary. Replete potassium <3.3 mEq/dL prior to initiation of insulin infusion. If the serum glucose does not fall by 50–70 mg/dL from the initial value in the first hour, the bolus should be repeated, and the insulin infusion may be doubled every hour until glucose steadily declines. When glucose values are <200 mg/dL, IV fluids should be changed to D5NS and insulin continued until the anion gap is <12 mEq/L. Ketosis may persist for up to 24 hours. Do not discontinue the insulin infusion until the anion gap is closed. Correct the anion gap for the albumin level. |

| Potassium | May be normal or elevated at admission due to insulin deficiency. Potassium distribution is reversed (driven intracellularly) rapidly during insulin infusion. K + 20 mEq/L is generally added to IV fluids and potassium levels carefully monitored and maintained between 4.0–5.0 mEq/L. |

| Bicarbonate | HCO3 can lead to rise in pCO2 resulting in paradoxic decline in cerebral pH as CO2 rapidly crosses the blood-brain barrier. Patients with pH <7.0 or life-threatening hyperkalemia may benefit from HCO3 administration. |

Abbreviations: BW, body weight; D5NS, 5% dextrose in normal saline; IV, intravenous; NS, normal saline.

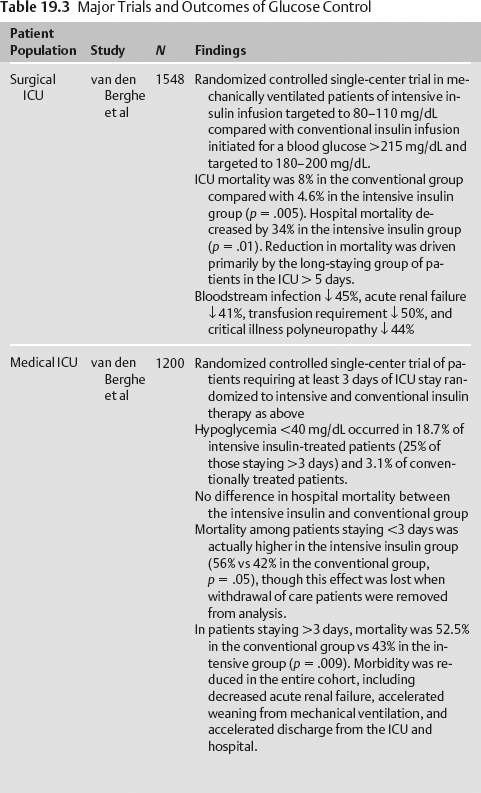

A summary of the major trials and outcomes of glucose control is given in Table 19.3.10–16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree