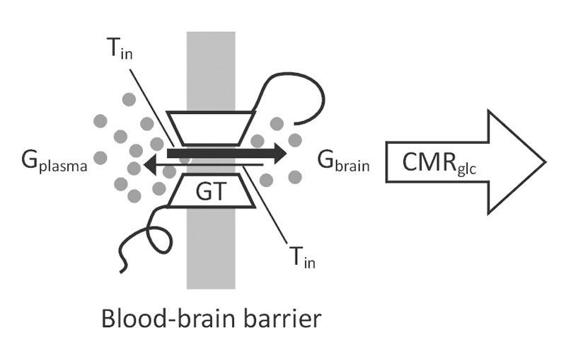

Figure 66.1. Direct relationship between brain and blood glucose levels.

Because glucose cannot freely enter the brain, it requires a transport system to cross the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier and the membranes of neurons and astrocytes. There are several glucose carrier isoforms present in the brain (Figure 66.2). The predominant glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins involved in cerebral glucose utilization are GLUT-1 and GLUT-3, with GLUT-1 present in all brain cells including the endothelial cells of the capillaries (with very low neuronal expression in vivo), and GLUT-3 which is almost completely restricted to neurons (reviewed in [36]).

Figure 66.2. Unidirectional model of glucose transport.

Both carrier proteins are facilitative glucose transporters that allow glucose to enter cells independently of insulin and are activated by cytokines released via inflammatory responses. They are also upregulated during periods of increased brain activity in order to optimize glucose transport according to demand.

Repressive adaptation of GLUT across the blood-brain barrier occurs in response to chronic hyperglycemia to prevent a rise in brain glucose content [37]. This glucose accumulation is avoided by bi-directional flux, which is influenced by the glucose concentration gradient (Figure 66.2) [36]. The different uptake kinetics according to the Michaelis-Menten equation (KM) guarantees glucose uptake even at low blood glucose levels, which is essential for neurons especially during hypoglycemia (GLUT3: 2.8 mM, GLUT1: 8 mM) [36]. Cerebral glucose consumption depends directly on metabolic activity and on a continuous systemic supply because the brain has no glucose reserves: the low glycogen stores available mainly in astrocytes are rapidly depleted within 2 minutes.

The central nervous system cells need a sufficient availability of substrate so they can generate energy to develop and maintain their functions. This is achieved at the expense of consuming glucose to generate ATP as well as CO2 and H2O.

The pathway that glucose must follow in order to produce energy is a multisequential and finely regulated process. It starts with glycolysis, a metabolic pathway by which glucose is converted into pyruvate or lactate, with the net production of 2 moles of ATP per mole of glucose. The generated pyruvate can then enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle or Krebs cycle: through this cycle and another process known as oxidative phosphorylation, 30 moles of ATP are produced per mole of glucose metabolized, making this metabolic pathway the most efficient one for producing energy.

The control of brain glucose concentration is very important for humans. Very low glucose concentrations can immediately induce seizures, loss of consciousness, and death, while chronic hyperglycemia induces changes in hippocampal gene expression and function [38].

As mentioned, glucose can originate intermediates such as lactate and pyruvate, metabolites which in certain circumstances can maintain neuronal activity. However, neither molecule crosses the blood-brain barrier freely, and because neither of the two have specific carriers they cannot replace glucose as a cerebral energy substrate in physiological conditions. Numerous studies have investigated molecules that could substitute glucose as an alternative substrate for brain energy metabolism. Among the vast array of molecules tested, mannose is the only one that can sustain normal brain function in the absence of glucose. Mannose crosses the blood-brain barrier and is converted to fructose-6-phosphate, a physiological intermediate of the glycolytic pathway, via enzymatic steps.

However, mannose is not normally present in the blood and therefore cannot be considered a physiological substrate for brain energy metabolism. Lactate and pyruvate can sustain synaptic activity in vitro [39,40]. Because of their limited permeability across the blood–brain barrier, they cannot substitute for plasma glucose to maintain brain function [41,42]. When formed inside the brain parenchyma, however, they are useful metabolic substrates for neural cells [41,42].

In certain pathological conditions such as fasting, malnutrition, diabetes, and ketonic states, acetoacetate and D-3-hydroxybutyrate are markedly elevated because they may be used by the brain as metabolic substrates. As a corollary to these studies, steady-state arterial-venous (A-V) differences provide indirect evidence that a substance can either be used as a substrate by the brain (a positive A-V difference) or produced by the brain (a negative A-V difference) from a particular substrate such as glucose. Thus, in ketotic states, positive A-V differences have been measured for acetoacetate and D-3-hydroxybutyrate, indicating net utilization under these particular conditions. A net release of lactate and pyruvate (a negative A-V difference) is occasionally found in normal individuals and more frequently in aged subjects or during convulsions.

This makes it clear that glucose is the brain energy plant and that it participates in various processes fundamental to brain cell activity. Glucose allows the proper functioning of ion channels, which are essential to maintain transmembrane transport; it enters the production of nucleic acids, amino acids and lipid and the synthesis of hormones and neurotransmitters such as glutamate, acetylcholine and GABA.

Brain energy metabolism can be measured by two techniques: the method of 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) and positron emission tomography (PET). The 2-DG method developed by Sokoloff and colleagues afforded a sensitive means to measure local rates of glucose utilization (LCMRglu) with a spatial resolution of approximately 50 to 100 µm [43]. With this method, LCRMglu has been determined in virtually all structurally and functionally defined brain structures in various physiological and pathological states, including sleep, seizures, and dehydration, and following a variety of pharmacological treatments [43]. Furthermore, an increase in glucose utilization following the activation of pathways subserving specific modalities, such as visual, auditory, olfactory, or somatosensory stimulation, as well as during motor activity, has been found in the pertinent brain structures [43].

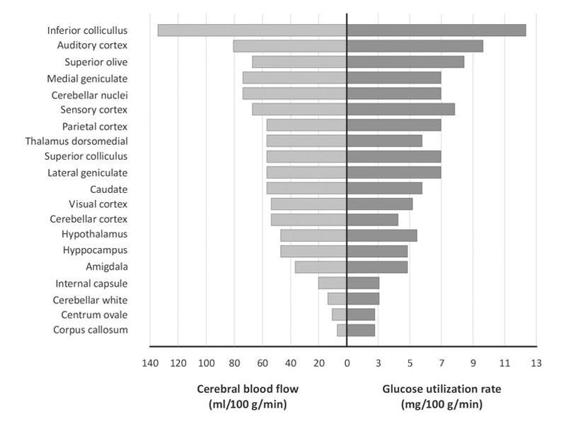

Similarly, local oxygen consumption and changes in blood flow can be studied in humans by means of PET using 15O2 and H215O and by means of local glucose utilization with 2-(18F)fluoro-2-deoxyglucose [44]. Both have revealed the characteristic features of glucose metabolism: regional heterogeneity and relationship with the developed activity (Figure 66.3). Glucose utilization by the gray matter varies between 5 and 15 mg per 100 g of tissue per minute. This variation depends on the brain region analyzed and that area’s specific function. The average rate of glucose consumed by the white matter is 1.5-2 mg/100 g/min. Physiological activation of specific pathways results in a 1.5 to 3-fold increase in LCMRglc, as determined by the 2-DG technique.

Figure 66.3. Regional differences in cerebral and glucose consumption.

Another interesting aspect of the two techniques is the simultaneous study of cerebral consumption of glucose and oxygen, together with blood flow, which has enabled and enhanced our understanding of phenomena occurring not only during functional activation but perhaps more importantly during situations of injury, clearly establishing a relationship between functional activity and energy metabolism.

Most current information on brain energy metabolism comes from studies of purified cell cultures enriched with astrocytes, neurons and endothelial cells. However, caution is warranted when extrapolating results obtained in vitro to in vivo situations. It is generally accepted, however, that insights may be gained from these cellularly homogeneous preparations. The results have allowed to review classic assumptions which considered neurons as the only metabolically active cell group and to properly reflect on what happens in the whole brain.

Although there are anatomical and structural differences between species, the neuronal population contributes up to 50% of the cerebral cortical volume. In addition, there are strong arguments for attributing astrocytes a key role in brain energy metabolism. Structurally speaking, there are 10 astrocytes per neuron, a relationship found in all brain regions studied.

Astrocytes are star-shaped cells strategically located around synapses; they possess receptors for a variety of neurotransmitters and reuptake sites mainly for glutamate. They differ from other cell types by having multiple extensions called “end-feet” in close contact with the wall of the capillaries where glucose transporters such as GLUT1 are expressed (Figure 66.2). Glutamate, the major excitatory amino acid, after exercising its function is taken up by astrocytes in the postsynaptic terminals and converted to glutamine, which is then released and taken up by neurons to maintain the neurotransmitter pool. This process results in the stimulation of aerobic glycolysis (requiring a sufficient amount of oxygen) and lactate production through a mechanism that involves activation of the sodium/potassium pump ATPase. Recent magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies in humans have shown that for every molecule of glutamate released from active synaptic terminals and captured by astrocytes one glucose molecule can be metabolized to lactate.

As noted earlier, in circumstances such as stimulation or vigorous activity, lactate can be used as an energy source by neurons although it doesn’t cross the blood-brain barrier: the situation is different when it is generated within the brain parenchyma. In summary, during neuronal activation lactate is released into the perisynaptic space, the astrocyte detects it and stimulates glucose uptake from the bloodstream. Glucose is metabolized to lactate, which is released and taken up by neurons to produce ATP via the Krebs cycle and oxidative phosphorylation.

Astrocytes have two well-established functions: 1) to maintain extracellular potassium homeostasis; and 2) to ensure neurotransmitter reuptake (mainly glutamate). They can also be involved in water regulation and exchange by activating aquaporins (AQP4), which are densely grouped on the extensions around the capillaries. Their shape and location suggest they play a key role in the transit of glucose from the bloodstream and in the coupling of energy metabolism to synaptic activity.

Earlier we mentioned that when the cells of the nervous system are active and energy-hungry, their main mechanism of energy supply is the increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF) to provide sufficient amounts of oxygen and glucose. This is accomplished by different types of signals: either metabolites such as lactate, adenosine, K+, H+, or neurotransmitters (vasoactive intestinal peptide, noradrenalin, acetylcholine) or nitric oxide. In this way, there is a “physiological coupling between CBF and energy metabolism” which is not always maintained, especially during injury.

66.3 Glucose Metabolism and Acute Brain Injury

During brain injury, whether of traumatic, hemorrhagic or ischemic origin, profound changes in brain energy metabolism occur [45-52]. The brain enters a state of energy dysfunction, called a “metabolic crisis” by some authors. Studies using microdialysis and PET techniques have discovered that this state of crisis may take several days to resolve and that it differs from cerebral ischemia. Energy dysfunction is characterized by its heterogeneity (not all brain areas are affected in the same way), and a marked decrease in oxidative metabolism and alterations in glucose metabolism. Immediately after primary brain damage, glucose use dramatically increases to ensure the supply of enough energy to meet the increased metabolic demands, thereby maintaining ion gradients and cell membrane function intact. This defence mechanism against injury has been called hyperglycolysis. It is short-lasting and followed by a period of decline in glucose utilization.

During this phase, secondary events such as seizures, intracranial hypertension, and hypoglycemia increase the demands on a tissue already working at diminished capacity, further compromising the limited energy reserves available to mitigate catastrophe.

Importantly, in pathological situations where the energy production is reduced and the cells cannot metabolize lactate aerobically, utilizing glucose acquires enormous significance. The main source of glucose derives from the extracellular space which, in turn, depends on an adequate supply and transport of glucose from the bloodstream. In these conditions, adequate glucose supplies to the brain might only be sustained when the concentration of systemic glucose is sufficient. Glucose can produce metabolic intermediates, such as lactate and pyruvate, which do not necessarily enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle but rather can be released and removed by the circulation. In this context, astrocytes play a role in glucose uptake by neurons by processing glucose through a glycolytic pathway and subsequently releasing lactate as a metabolic neuronal substrate [53].

Glucose metabolism in neurons is directed mainly to the pentose phosphate pathway, leading to the regeneration of reduced glutathione. Neurons die rapidly following the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration, whereas astrocytes utilize glycolytically generated ATP to increase their mitochondrial membrane potential, thus becoming more resistant to pro-apoptotic stimuli [53].

The increase in glucose utilization, together with a higher cerebral metabolic rate in the immediate hours following acute brain injury, lead to an increase in the capillary density of GLUT1, facilitating the transport of glucose from the blood to the brain interstitium [54]. The significant increase in GLUT3 and significant decrease of GLUT1 in neurons [55] suggest a mechanism of autoprotection against hypoglycemia due to the increased expression of high-affinity GLUT3 transporters (Km 2.8 mM) [55]. However, the lack of activity of the 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose 2,6-bisphosphatase, isoform 3 (PFKFB3), leads to a state of sustained brain energy dysfunction in both animals and humans and may eventually contribute to poor outcome [56,57]. Furthermore, transport of glucose at the blood-brain barrier and the neuronal plasma membrane may become inadequate to satisfy brain cellular metabolism.

The initial phase characterized by compensatory hyperglycemic glycolysis is typically followed by a regionally heterogeneous reduction in energy consumption, with a reduction in cerebral metabolic oxidative metabolism and alterations in glucose metabolism [58]. Rapid-sampling microdialysis studies in patients with acute brain injury including ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and intracerebral hemorrhage [59] showed an inverse relationship between the rate of depolarization and the changes in tissue glucose, the highest rate being found in patients with the greatest falls in brain glucose levels. These results indicate a potential for a deficiency in the availability of extracellular glucose after severe brain injury which, in turn, is associated with worse neurological outcome.

Due to their expression of NMDA and non-NMDA receptors, neurons and oligodendrocytes are exquisitely sensitive to excitotoxicity by glutamate, which reaches high extracellular concentrations in brain injury for several reasons, including failing astrocyte uptake [53]. Excitotoxicity kills brain cells by energetic exhaustion (due to Na+ extrusion after channel-mediated entry) combined with mitochondrial Ca2+-mediated injury and the formation of reactive oxygen species.

Many but not all astrocytes survive energy deprivation for extended periods, but after returning to aerated conditions they are vulnerable to mitochondrial damage by cytoplasmic/mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) deficiency. Ca2+ overload is established by reversal of Na+/Ca2+ exchangers following Na+ accumulation during Na+-K+-Cl– co-transporter stimulation or pH regulation, compensating for excessive acid production [53]. NAD+ deficiency inhibits glycolysis and eventually oxidative metabolism secondary to poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP) activity following DNA damage. This results in reduced pyruvate levels due to insufficiently replenished NAD+ and increased lactate levels due to metabolic short-cutting because pyruvate is metabolized to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase and cannot enter the citric acid cycle. Maintaining adequate intracerebral glucose levels can be beneficial for neurons, whereas excessive hyperglycemia increases astrocyte death due to enhanced acidosis.

66.4 Hypoglycemia-induced Brain Damage

Although there is no unanimous agreement, hypoglycemia in adults is defined as a decrease in serum glucose levels <50 mg/ dl (<2.8 millimol/l), regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms. The severity of a hypoglycemic episode is determined by the plasma glucose concentration together with the appearance of symptoms and changes in brain electrical activity [32,60-72]. The changes evidenced on the electroencephalogram (EEG) cover a wide spectrum from cortical slowing with predominantly theta and delta waves to silence or flat EEG through the suppression of wave patterns (“burst suppression”) and/or seizure activity. Glycemic thresholds that trigger symptoms or EEG impairment vary widely from individual to individual, even among non-diabetics and diabetics; indeed, fluctuations are noted among the latter regardless of whether glucose levels are under control or not.

However, several authors have underscored a key concept to bear in mind: hypoglycemia-induced brain injury occurs most often in patients in whom a strict control of blood glucose with insulin is attempted.

Hypoglycemia-induced brain damage is characterized by its depth or severity and duration. Brain energy metabolism is altered when one or both characteristics are present. This concept is important to emphasize because cerebral oxygen consumption remains unchanged during episodes of hypoglycemia, thus suggesting that alternative metabolic substrates are being utilized to ensure the production of ATP needed to maintain cellular functions.

From the physiological concepts described above it is clear that the work and survival of cells that make up the CNS is highly dependent on a continuous supply of glucose. The brain has a limited ability to adapt to situations of marked decrease in glucose intake. There are three compensatory mechanisms that counteract brain glucopenia: response to stress; increase in CBF; use of alternative reservoirs and substrates.

The systemic response to hypoglycemia is predominately via the release of counterregulatory hormones. Numbering among these hormones are catecholamines, glucagon, cortisol, and others. All favour the release of glucose into the bloodstream (hyperglycemia) in the attempt to preserve CNS cell function. Although several working groups have shown a marked increase in CBF during episodes of hypoglycemia, its pathophysiological mechanisms are not entirely clear. The extent of the increase in CBF depends on the severity of hypoglycemia. In addition, the cerebral blood vessels lose their ability to regulate their diameter in response to changes in perfusion pressure, i.e., the ability to self-regulate CBF. The astrocyte glycogen stores are depleted within 5 minutes. However, recent studies suggest that glycogen can be used longer, particularly when the supply of glucose to the brain is insufficient or when hypoglycemia is repeated.

Other endogenous substrates of energy utilized by the CNS cells both in vivo and in vitro are amino acids and fatty acids such as arachidonic acid, both of which are insufficient, inefficient and dangerous, since they induce the accumulation of products (e.g., oxygen free radicals, calcium) which are potentially toxic and lethal for neurons. Profound metabolic disorders ensue when the ability to cope with hypoglycemic insult fails or is depleted. Since glucose, besides being the brain’s ultimate energy source, is involved in other vital processes, its lack or absence prevents amino acid metabolism, protein synthesis, neurotransmitter release, alters the local pH, and damages the cell membranes when ion channels don’t work correctly.

As mentioned, the more profound and prolonged the hypoglycemia, the greater the likelihood of severe and irreversible damage. Multiple mechanisms are involved in neuronal death, including glutamate and adenosine toxicity, apoptosis, oxidative damage by oxygen free radicals, zinc and nitric oxide, and the accumulation of intracellular calcium.

Not all brain regions show the same susceptibility to damage induced by hypoglycemia. The cerebral cortex, striatum and hippocampus are among the most vulnerable areas, while the hypothalamus, cerebellum and brain stem are highly resistant to hypoglycemic injury. Autopsy studies in humans have revealed scattered petechiae, congestion and edema of nerve cells, mainly located in axons and dendrites, which undergo a series of degenerative changes and subsequently disappear. Many areas of glial reaction, demyelination, and encephalomalacia can be found.

66.5 Hyperglycemia as a Prognostic Factor

When defining hyperglycemia in the context of serious illness in general and in patients with neurological/neurosurgical emergency in particular, the lack of a uniform definition in different series studied should be taken into account.

The values used to define it widely vary and were taken arbitrarily [1-21]. Nevertheless, it is estimated that the incidence of hyperglycemia in the neurocritical patient ranges between 28 and 68% [7,10,73]. Hyperglycemia is also an independent risk factor of mortality and poor functional outcomes in several situations of neurological injury such as ischemic stroke treated or not treated with thrombolysis [2-10,73-81], spontaneous intracerebral [18-21,82,83] and subarachnoid [11,12,84-87] hemorrhage, malignant brain tumors [88], severe head injury [13-17], and spinal cord injury [89-93].

Multiple studies have demonstrated the negative impact of hyperglycemia in the ischemic brain. Williams [6] showed a close association between hyperglycemia and mortality at 30 days, 1 year and 6 years after ischemic stroke. Capes et al. [5] in their meta-analysis showed that the risk of death after ischemic stroke was 3 times higher if blood glucose levels at hospital admission were between 110 and 126 mg/dl.

In a recent study, Stead et al. reported results similar to those above, because patients with cerebrovascular disease and hyperglycemia are 2.3 times more likely to die at 90 days compared to patients with normoglycemia [84]. The multicenter, prospective observational GLIAS study [81] established as its main objective to detect the glucose threshold with the greatest predictive power of poor outcome in the acute phase of ischemic stroke. The optimal cut-off point that most accuracy predicted poor outcome 3 months after the event is 155 mg/dl. This value is correlated with a 2.7-fold increase in the probability of poor outcomes after adjusting for variables such as age, presence of diabetes, glucose level at admission, infarct volume and stroke severity, while the risk of death is 3 times greater (hazard ratio [HR] 3.80, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.79-8.10) [81].

Hyperglycemia is a common finding in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage [18-21,82-83] and has a detrimental prognostic effect in the short term according to some studies (odds ratio [OR], 1.52; 95% CI 1.28-1.82; p <0.0001) [21].

Our working group investigated the relationship between early mortality, i.e., within 30 days after intracerebral hemorrhage, and elevated levels of blood glucose [21]. Patients who died had high blood glucose levels for 72 hours after the stroke (p <0.001). It is noteworthy that for each 18 mg/dl increase in glucose levels >90 mg/dl, the probability of experiencing a fatal event increases by 33%. The cut-off point in which the greatest predictive power is obtained is >164 mg/dl. All the above findings apply equally to diabetic and non diabetics patients [21].

Elevated glucose levels have been identified as independent predictors of final outcome after SAH [12,85-87]. A study by Frontera demonstrated a close association between hyperglycemia and the onset of complications such as heart and respiratory failure, pneumonia and brain herniation (p <0.05). Also, a close link was demonstrated between hyperglycemia and poor outcomes defined as either severe disability or death (OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.07-1.28; p <0.001) [12].

The Dutch group led by Kruyt [85] evidenced, after multivariate adjustment of baseline characteristics of non-diabetic patients with aneurysmal SAH, that the average levels of fasting glucose during the first week following initial bleeding predicts poor outcomes (OR 2.5; 95% CI 1.4-4.6) better than blood glucose at admission (OR 6.1; 95% CI 0.9-2.7) [85].

The deleterious effects of hyperglycemia on the injured brain in neurotrauma are well known. It is a factor of secondary damage to be avoided. However, currently available evidence is scarce and controversial at best, so we cannot definitively say whether high blood glucose levels are an independent risk factor of poor outcome after severe head trauma.

The few available studies show that patients with blood glucose >170 mg/dl have worse long-term results compared to subjects with normal blood glucose levels [13,16,17,89]. Salim et al. retrospectively analyzed a series of patients with severe TBI. Persistent hyperglycemia was defined as ≥150 mg/dl during the first week post-trauma was prevalent in older patients with a greater severity of head and systemic trauma, and on multivariate analysis independently predicted mortality (OR 4.91; 95% CI 2.88-8.56; p <0.0001) [90].

The degree of hyperglycemia seems to be important in prognosis [16]. Some predictive models have included hyperglycemia as a prognostic factor thus improving the prediction of outcomes [91-93].

Experimental models of spinal cord ischemic injury have shown that high blood glucose levels adversely affect neurological function [94-96]. In Only one retrospective study concluded that after traumatic spinal cord injury hyperglycemia accompanies the most severe contusions, while hyperglycemia induced after spinal cord ischemia does not affect the final outcome [97].

66.6 Pathophysiology of Hyperglycemia in the Acute Phase of Brain Injury

The genesis of hyperglycemia after brain damage is not due to a single cause; instead, various multifactorial [10] mechanisms are involved [73] (Table 66.1). One hypothesis is that hyperglycemia is nothing more than an indicator of pre-existing and/or undiagnosed diabetes (intolerance to glucose); however, this hypothesis has not garnered much acceptance as many studies have shown that hyperglycemia in the absence of diabetes is by itself a risk factor of poor outcome in several neuroinjury scenarios [5-10,12-17,19-21,98,99].

|

Table 66.1. Pathophysiology of hyperglycemia in acute brain injury.

Perhaps the most widely accepted explanation is that hyperglycemia during the early phase of neuroinjury is due to a non-specific reaction or response to “stress” situations [2,10,100-103]. This programmed, coordinated and adaptive response is of paramount importance for survival.

It has 3 main components: 1) Activation of the immune-neuroendocrine hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, with the subsequent release of counterregulatory and hyperglycemic hormones, such as catecholamines, cortisol, etc.; 2) Autonomic nervous system stimulation; 3) Modification of individual behaviour.

Each component to a different degree and in a different way contributes to the development of hyperglycemia, so that the greater the damage, the greater the response. Thus, hyperglycemia may be a marker of injury severity rather than a phenomenon that can worsen or trigger it. As mentioned, however, the prevalence of hyperglycemia is high, and independent of the type and severity of the neuroinjury [7,10,73,103]. Furthermore, studies which have reported a causal and unequivocal relationship between stress hormones and stroke are inconsistent [104].

Neuroendocrine dysregulation secondary to anatomic lesion of the insular cortex is one of the mechanisms thought to explain hyperglycemia [105,106] but evidence has not been sufficiently confirmed by other authors [107].

Inflammation triggered by CNS injury is another potential cause of hyperglycemia [100,108-116]. When brain damage of whatever origin occurs, a wide range of mediators including cytokines is immediately released mainly by astrocytes and microglia. Cytokines can, in turn, trigger hyperglycemia through the induction of insulin resistance in the liver and muscle.

The resulting hyperglycemia, coupled with the increased generation of glucose by the liver secondary to the above-mentioned metabolic response to stress, leads to glucose overload that perpetuates the inflammation and triggers the injury of endothelial cells [100,108-116]. In practical terms, we must take iatrogenic causes into account, since many drugs in routine neurointensive care (e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine, steroids, thiazides, dextrose-containing solutions, among others) can potentially trigger hyperglycemia [106,117-119]. In this context, adequate nutritional support is essential, given the multiple physiological changes triggering the injury. Among the less convincing hypotheses, or rather those not sufficiently backed in the literature, are those that seek to explain direct hypothalamic damage or irritation of the centres regulating blood glucose after neuroinjury [10].

66.7 Temporal Profile

Technological advances and the development of new monitoring techniques have greatly improved our understanding of the various phenomena occurring after brain damage, many of which can establish, perpetuate and worsen the initial injury. Hyperglycemia is one such factor. Although there is no a uniform and unanimous definition of hyperglycemia in the context of neuroinjury, cut-offs used to define it vary from study to study and most were obtained in an arbitrary manner from the analysis of retrospective series [2-21,70-87]. There are several forms of monitoring and all of them determine glucose levels by an enzymatic or electrochemical method based on the reaction of glucose oxidase.

Blood glucose values can be obtained in the following ways: intravenous or arterial; capillary, “pricking” the fingertips; subcutaneous using a sensor inserted into the abdominal wall to record interstitial glucose values [76,120].

The units of expression of blood glucose values are standardized: 1) milligrams per decilitre (mg/dl) or 2) millimoles per litre (mmol/l), as expressed by most European studies.

Hospital admission is the moment most authors select when analyzing the prognostic role of elevated blood glucose values during CNS injury [2-21,73-84].

Like other biological variables, however, blood glucose is characterized by its dynamic fluctuating nature because it is subject to variations induced by: nutrition, stress situations (pain, trauma, surgery), drugs, and other factors. Therefore, it is logical to think that the deleterious effects of hyperglycemia persist beyond the first few hours after injury, making serial monitoring of blood glucose levels during brain damage of paramount importance.

Few studies have elucidated the behaviour over time of blood glucose values. Baird [76] in a small series of patients reported that 35% had hyperglycemia at admission, in 43% of which high levels persisted over the study period (72 h post-ischemic stroke), whereas 46% with normal values at the admission in hospital developed hyperglycemia.

Hyperglycemia is strongly associated with infarct expansion (r ≥0.60, p <0.01) and poor functional outcome on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale ([NIHSS] r ≥0.53, p <0.02) or the modified Rankin scale ([mRS] r ≥0.53, p=0.02) [76].

Allport et al. [120] described two phases of occurrence of hyperglycemia in a series of 59 patients suffering from ischemic stroke: an early stage occurring in all diabetic patients and 50% of non-diabetic patients within 8 hours after the stroke, and a late phase (48-88 hours post-stroke) in 27% of non-diabetic and 78% of diabetic patients.

The recently published GLIAS study [81] highlights that hyperglycemia occurring within the initial 48 hours post-ischemic stroke is most important factor in determining the final results, regardless of the presence of known and widely validated predictors such as age, presence of diabetes mellitus, infarct volume and stroke severity.

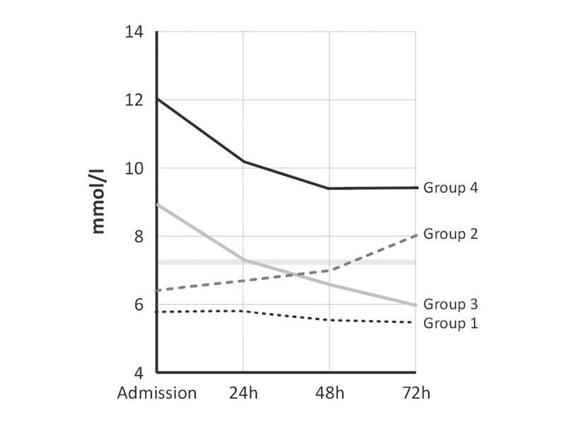

In turn, Godoy et al. [21] identified four evolutionary patterns in a series of nearly 300 patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage; but perhaps most important was the relationship between different groups and mortality: the mortality was 8.6% among patients with normal blood glucose values and 79.5% for those with persistent hyperglycemia during the study period (p <0.0001).

The main conclusions highlight that hyperglycemia is common, of long duration and with different evolutionary profiles in neurocritical patients. Additionally, it is strongly associated with death and poor functional outcomes.

66.8 Mechanisms of Hyperglycemia-induced Brain Injury

The body’s cells naturally protect themselves against the potential toxicity of hyperglycemia by regulating glucose transporters [24,121]. Some cell groups, including neurons, astrocytes, hepatocytes, epithelial and endothelial cells, and the cells of the immune system, receive glucose (without using insulin) from transporter proteins GLUT 1, 2 and 3, which are responsible for facilitating the entry of this energy source into the cell [24,121].

During injury, local hypoxia and the release of mediators (e.g., cytokines, angiotensin II, endothelins) stimulate GLUT expression and localization on the cell membranes, thus deranging the cell’s the defence system, ensuing in a glucose overload in the cellular microenvironment [24,122-126].

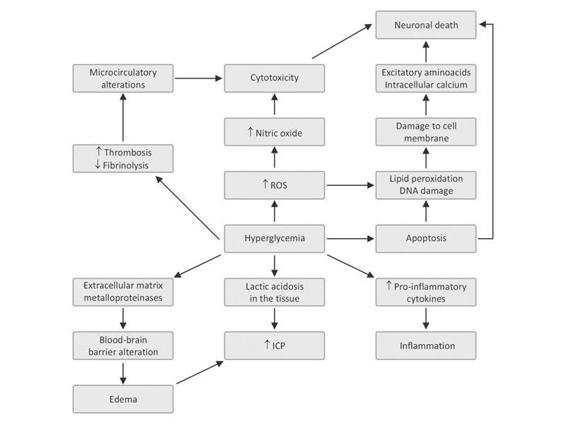

Although the precise mechanism of hyperglycemia-induced neuronal damage is not known, multiple factors, either together or isolated, interact to trigger, perpetuate or exacerbate the injury. In two elegant papers, Garg [10] and Tomlinson [127] reviewed the potential mechanisms involved. Briefly:

66.8.1 Reduced Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF)

A decrease of up to 25% has been shown in experimental animals [128,129]. Nitric oxide seems to play a key role: neutralizing it or inhibiting its production by the vascular endothelium produces an imbalance in cerebral vascular tone where vasoconstriction predominates. The trend towards microthrombosis of cerebral capillaries triggered by inflammatory mediators such as tissue factor is associated with this mechanism. In occlusion-ischemia models it has been observed that the decrease in flow also involves the penumbra area, showing that the initial area of infarction can be increased when hyperglycemia is present.

66.8.2 Metabolic Dysfunction

Kushner’s study with PET and 2-deoxyglucose technique described a profound metabolic depression in the ischemic brain in patients with an average blood glucose level >155 mg/dl [130]. The hypometabolism may be due to impaired mitochondrial function secondary to the toxic effects of glucose overload or to the local lactic acidosis generated during hyperglycemia [10,130].

66.8.3 Toxicity Due to Excitatory Amino Acids and Calcium

Hyperglycemic states increase the availability of extracellular glutamate which activates postsynaptic NMDA receptors to open ion channels, thus allowing the massive entry of calcium into the cells, with consequent mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal death [10,131]. Hyperglycemia also prevents the reuptake of calcium into the cell after reperfusion in cerebral ischemia models; therefore, it becomes a threat or impediment to the recovery of damaged tissue in such situations [132].

66.8.4 Inflammation

The injury-induced hyperglycemia and tissue damage trigger a complex series of events, among which inflammation and oxidative stress, resulting in the released of mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, oxygen free radicals which, in turn, aggravate the injury through several and varied mechanisms [10,119]. It is well known that the oxygen free radicals cause peroxidation of cell membrane lipids, carboxylation of proteins vital to cell function, and denaturation of DNA. Moreover, they also inhibit the endothelial production of nitric oxide or block its action [10,119,133].

Cytokines perpetuate the inflammatory activity [134] and induce the production and/or transcription of extracellular matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which will play a major role in damaging the blood-brain barrier and causing cerebral edema [135,136]. Also, hyperglycemia compromises cerebral microcirculation by altering the balance between thrombotic and fibrinolytic factors [10].

As a corollary, we can deduce that the mechanism of injury analyzed in isolation or together with other phenomena clearly explains the development of certain complications in neurocritical diseases: hemorrhagic transformation [4,77,79] and/or expansion of cerebral infarction [76] or spontaneous enlargement of intracerebral hematoma [136], and vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage [11,12,137].

Figure 66.4. Mechanism of brain damage during hyperglycemia.

ICP = intracranial pressure; ROS = reactive oxygen species.

66.9 Insulin: Neuroprotector?

Insulin, a key hormone in the control of intermediate metabolism, was isolated from the pancreas by Benting and Best in 1922 [138]. It has a profound effect on the metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids and a significant influence on protein metabolism. It plays a major role in mineral metabolism and energy storage.

Unlike other body tissues, the cells of the human CNS are highly permeable to glucose: they capture and utilize without requiring the action of insulin, i.e., cerebral glucose consumption and metabolism depends almost exclusively on the contribution and availability of glucose in the blood, its main vehicle of transport [24,121,139-141].

Evidence from experimental cerebral ischemia models has shown that, besides its physiological actions on blood glucose levels, insulin possesses certain neuroprotective properties by significantly reducing neuronal necrosis [10,73,142-145].

Insulin has recently been shown to exert a potent anti-inflammatory action in vivo and in vitro by blocking the production of pro-inflammatory agents, the generation of oxygen free radicals and the synthesis of MMPs [146-152]. As a result, this action of insulin increases the release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells, astrocytes and neurons, which would favour the maintenance of adequate blood flow [153-156].

Insulin decreases the expression, transcription and synthesis of MMPs, so that tissue damage is limited by keeping the blood-brain barrier intact [152]. Additionally, insulin has antiplatelet, anticoagulant and profibrinolytic effects [10,73,156-159]. These mechanisms enhance insulin’s anti-inflammatory action and hypothetically may improve cerebral microcirculation.

Other benefits of insulin derive from its physiological action. Since it is an anabolic hormone, it promotes protein synthesis, thereby stimulating neuronal repair and regeneration [10,73,156].

Figure 66.5. Changes in blood glucose levels during initial 72 hours after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in 295 patients. Different patterns were observed: persistently normal (group 1), increasing (group 2), decreasing (group 3), and persistent elevation (group 4).

66.10 Management of Glycemia in the Neurocritical Patient According to Clinical Practice Guidelines

The term “evidence-based medicine” (EBM) was first used in the 1980s to describe a new learning strategy used at McMaster Medical School, Canada, which stressed the importance of reviewing evidence from investigation, and cautious interpretation of the clinical information derived from non-systematic observations [160].

According to the definition by Sackett in 1996 [161], “Evidence-based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients”.

Next, we will review past and present guidelines for the management of glycemia in different situations of acute brain injury.

Organization | Year | Cutoff to start treatment (mg/dl) | Evidence level |

Severe traumatic brain injury | |||

BTF | 2000 | NS | – |

BTF | 2007 | NS | – |

Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage | |||

AHA | 1999 | NS | – |

EUSI | 2006 | >300 | IV |

AHA | 2007 | >185 | IIa C |

Subarachnoid hemorrhage | |||

AHA | 1994 | NS | – |

AHA | 2009 | NS | – |

Ischemic stroke | |||

AHA | 1994 | NS | III-IV C |

AHA | 2003 | >300 | C |

EUSI | 2003 | >180 | IV |

AHA | 2007 | 140-185 | IIa C |

EUSI | 2008 | >180 | IV |

Ischemic stroke with thrombolytics | |||

AHA | 1996 | >400 | – |

Table 66.2. Recommendations for hyperglycemia management during acute cerebral injuries according to current guidelines.

AHA = American Heart Association; BTF = Brain Trauma Foundation; EUSI = European Stroke Initiative; NS = not specified.

66.10.1 Ischemic Stroke (IS)

All current recommendations have a common denominator when dealing with early detection, prevention and rapid correction of hypoglycemia since its deleterious role is well known in situations of acute brain injury (Class I, Level of Evidence Grade C) [162-167].

In the management of elevated blood glucose levels, according to then available evidence, the expert committee of the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association (AHA) stated in 1994 that the association between hyperglycemia and poor outcomes is uncertain and controversial. Nevertheless, it suggested treating hyperglycemia, without specifying guidelines or thresholds (Level of Evidence III-IV, Grade C) [162].

Later, in 1996, the AMA issued guidelines for thrombolytic therapy in ischemic stroke which advised keeping blood glucose values between 50 and 400 mg/dl [163]. A decade later, the AHA recognized the harm of hyperglycemia in the context of ischemic stroke, suggesting a cautious approach to hyperglycemia control, i.e., to keep levels <300 mg/dl (Level of Evidence Grade C) [164-165].

At the same time, the working group of cerebrovascular diseases in the European Stroke Initiative (EUSI) emphasized how frequent and dangerous hyperglycemia is during the acute phase of ischemic stroke, recommending the control of blood glucose values >180 mg/dl (Level of Evidence IV) [166].

Recently, the AHA and EUSI updated their guidelines in which hyperglycemia is recognized as a common phenomenon accompanying ischemic stroke in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients, highlighting its role in triggering and/or maintaining secondary injury, associated with such complications as expansion or hemorrhagic transformation of infarcts and poor outcome.

The AHA now recommends keeping blood glucose levels <185 mg/dl, suggesting also a possible, hypothetical additional benefit obtained by treating values >140 mg/dl (Class IIa, Level C) [167]. In contrast, the 2003 EUSI guidelines (Level of Evidence IV, GCP, remain unchanged [168].

66.10.2 Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (sTBI)

In 1995 and 1997, respectively, the Brain Trauma Foundation [169] and the European Brain Injury Consortium (EBIC) [170], presented the first recommendations for the management of TBI patients. The recommendations were updated in 2000 [171] and again in 2007 [172].

In the section on nutrition, all versions of the document stress that hyperglycemia is a contributing factor to secondary injury and that its presence worsens the prognosis. But there is no mention of cut-off points up- or downwards at which treatment for altered glucose levels should be initiated.

66.10.3 Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH)

The Stroke Council of the American Heart Association in 1994 [173], and again in 2009 [174], published clinical practice guidelines for the management of SAH following the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm. Similarly to the recommendations for the management of TBI, they only highlight that hyperglycemia should be avoided owing to its detrimental role in the pathophysiology of brain damage but without specifying how or when this should be done.

66.10.4 Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage (sICH)

In 2007, the AHA updated their guidelines for the treatment of acute phase of sICH. In contrast to the first edition [175], hyperglycemia is recognized as a component of the body’s response to brain injury, its presence is identified as a marker of the severity of damage, and is associated with poor outcomes in the short and long term.

Additionally and more importantly, they establish (Level of Evidence IIa, level C), the threshold for initiation of insulin therapy [176] starting at 185 mg/dl (possibly >140 mg/dl). In turn, the European Initiative (low level of evidence), suggested keeping blood glucose levels <300 mg/dl [177].

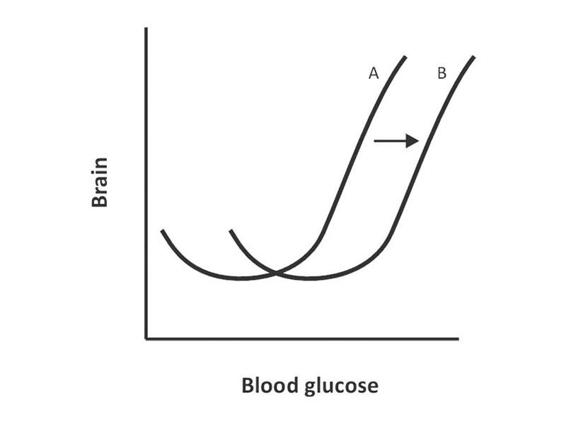

Figure 66.6. Hypo- or hyperglycemia increases the possibility of brain damage (A). During injury there is a shift of the curve towards B, showing an increased need for glucose by the brain, as well as increased susceptibility to glycogenesis in such situations.

66.11 Intensive Insulin Therapy

There are two treatment options to decrease blood glucose levels in diabetic patients: insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs). The latter have no place in the treatment of hyperglycemia in critical illnesses owing to circumstances that can alter their pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

The effects of many drugs commonly used in intensive care are enhanced or antagonized by OHAs. In addition, in critically ill patients a drug’s bioavailability, volume of distribution and metabolism are all altered due to increased capillary permeability, hepatic and renal dysfunction [178].

Another important aspect to consider is the mechanism of action of OHAs. These drugs act by promoting insulin secretion and action by augmenting its receptor function. In contrast, in the critically ill patient, due to the metabolic response to stress-induced injury, the ability to release insulin is reduced and insulin resistance is increased [100,108-116].

Finally, one of the most feared side effects of OHAs is hypoglycemia, which is often very severe, prolonged and life-threatening, especially in neurocritical patients [60-72,178].

There are several routes and forms to administer insulin. The intravenous (IV) route is the one most frequently used in critically ill patients. Administration regimens vary. Some working groups prefer to correct the blood glucose levels in a phased manner and according to monitoring: this scheme is called “reactive”. Instead, others estimate the requirements, trying to keep blood glucose levels within a preset range, and this regimen is known as “proactive”. Both regimens have their pros and cons, but none has shown superiority or advantage over the other [73].

On the basis of the available evidence for the detrimental role of hyperglycemia, in 2001 van den Berghe published the results of a new therapeutic modality called intensive insulin therapy which aimed at maintaining blood glucose levels within a narrow range, i.e., between 80 and 110 mg/dl [22].

This prospective, randomized single-centre study included postoperative patients on mechanical ventilation, two thirds of which had undergone cardiac surgery. When compared with the group in which blood glucose levels were maintained between 180 and 200 mg/dl, a significant decrease in mortality is observed (8% vs. 4.6%; p <0.04) especially in the patients who remained in critical care for more than 5 days, had proven septic focus, and developed multiple organ dysfunction (20.2% vs. 10.6% for those treated with conventional and intensive regimen, respectively; p <0.006).

Additional benefits obtained from IIT were a lower incidence of infection, days on mechanical ventilation, hospital mortality, development of polyneuropathy of critical ill patients, and need for blood transfusions or dialysis in patients with acute renal failure.

The authors could not replicate the previous data in a series of patients with non-surgical pathology, except in a small subpopulation requiring critical care stay for more than 3 days [179].

Years later, the results of other multicenter studies that questioned the findings of the Belgian group were disclosed [180-184]. Brunkhorst in Germany applied prospectively and randomly IIT to septic patients. Not only was there no difference in mortality between the study groups but also the trial had to be aborted, upon the suggestion of the safety committee, because of the high rate of severe hypoglycemia [180].

Similar data were reported in diabetic and non diabetic patients, victims of acute myocardial infarction [182,183], and in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients [184].

The prospective, randomized multicenter NICE-SUGAR study involving critically ill patients with different medical and surgical pathologies compared two goals in glycemic control. In one group, IIT was aimed at maintaining blood glucose between 81 and 108 mg/dl (intensive), while in the other one the objective to achieve slightly higher levels between 144 and 180 mg/dl (conventional).

At 90 days after admission to the ICU, the mortality in the intensive group was significantly higher (27.5% vs. 24.9%; OR 1.14; p=0.02), as was the incidence of severe hypoglycemia (6.8% vs. 0.5%; p <0.001), whereas there were no differences between the two therapeutic arms when comparing number of days on mechanical ventilation, length of ICU or hospital stay, or need for dialysis [185].

Therefore, to date, no accurate conclusions can be drawn as even the available meta-analysis of IIT come to different conclusions [186,187].

66.12 Can or Should the Data Obtained in Critically Ill Patients in General Be Extrapolated to Patients With Acute Brain Injury?

This patient subpopulation deserves special consideration. Some authors have approached the subject partially and from different perspectives [73,80,188,189]. While there is unanimous agreement that elevated serum glucose levels or hypoglycemia contribute to secondary damage and worsen the prognosis of these patients, there is no consensus on delineating the levels at which glucose should be maintained.

Although there are no studies specifically addressed to hypoglycemia, the body of available evidence says that there is no doubt that it must be avoided and/or treated in an urgent and aggressive way [60-71,162-177,190].

The debate about hyperglycemia is more complex and focuses on two unsolved questions:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree